*Hey everyone: If you appreciate my work, can you do me a favor? PLEASE:

*Recommend* Sincere American Writing on your Substack. This really helps to gain subscribers.

Subscribe for free if you haven’t already

Consider going paid for only $35/year ($2.91/month, the price of a cup of coffee)

Please spread the word about Sincere American Writing

***Two final comments:

1. 80 old paid posts have been unlocked and are now free.

2. Read my fictional NYC Covid memoir and my prison suspense novel in full (first 4-5 chapters free, the rest paid) all in one place in new section tabs on the homepage, Two Years in New York and The Grim Room.***

***

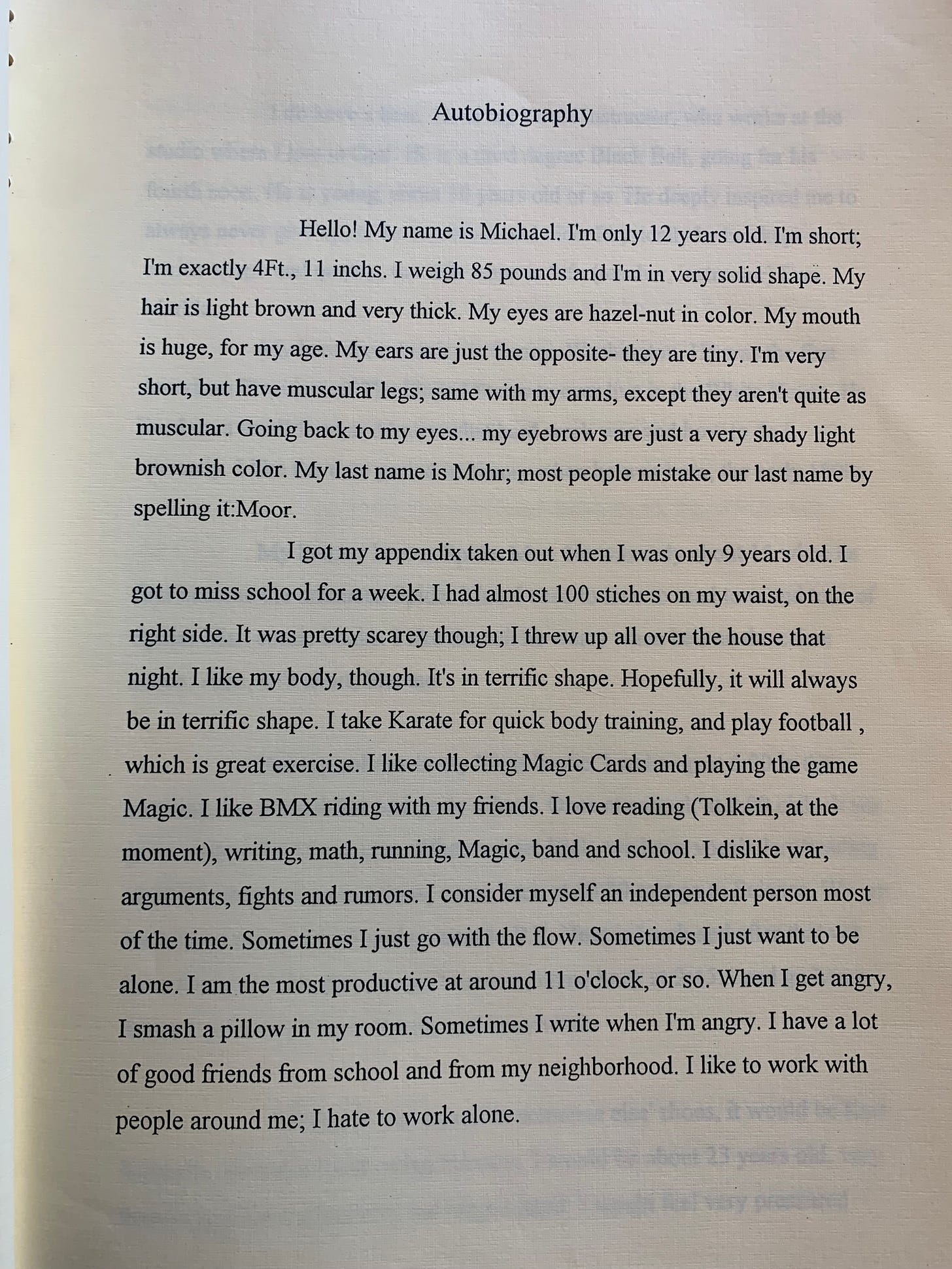

In 1997—when I was 14—as a Mother’s Day gift, I presented my mother with a collection of my writings. The collection is entitled My Writings. It covers a wide range of styles, genres and topics, from karate to Spider Man to detective stories to science fiction-writing to poetry and more. There’s also a mini autobiography, which, with the passage of time, strikes me as both semi-brilliant, ridiculous and tragicomic all at once.

Posted along the way of this essay are some fragments and whole pieces taken as photos from the collection. I also quote a few paragraphs; I left the punctuation, grammar, syntax and historical inaccuracies intact. Rereading some of my writing from childhood, I feel I could have been either a serious writer, a vagabond, suicidal, or a standup comedian. (I’m relatively certain that 98% of my writing back then was sincere and not intending humor. I was a child, of course.)

I was born on New Year’s Eve (December 31st), 1982. The first eight years of my life were lived in a small yellow house in a cul-de-sac up on a steep hill in Ventura, California, a little surfer town an hour or so north of Los Angeles bisected by the famous Highway 101. A little after I turned eight—in 1991—we moved to Ojai, the tiny 8,000-population mountain town 12 miles east of Ventura covered with orange groves, the Los Padres Mountains, the Topa Topa Mountains, the spectacular Ojai Valley, and ritzy hotels, coffee shops, restaurants and snazzy tourist shops.

Me being me, I rejected all of that and turned, in high school, to booze, girls, trouble and punk rock. The revolution—for me—started in 1999. The government I was toppling was the oppression of parents, the bourgeois, and Catholic college-prep high school.

But writing had always been there, too, hovering just beneath the surface. Mom had been a copywriter once, briefly, in her teens growing up in Pacific Palisades in the 1960s. Mom’s brother—my black sheep uncle—had studied screenwriting at UCLA and had become, among other things, an unpublished novelist. Two cousins later became writers, one doing travel writing and the other videogame writing.

Mom, later, wrote humorous nonfiction stories about pugs for a national magazine called Pug Talk. And then she wrote both fiction and nonfiction books which she eventually had published. She was a writer; it was in her blood. Though her own mother hadn’t been a writer, she had been a voracious reader.

And reading was something I most certainly learned from my mother. Growing up in Ojai, in the house of my angsty growing up, between 1991 and 2003, Mom had a brilliant, classic library. I still recall with vivid acuity the living room in the house we lived in on La Luna Street, the house with the long, verdant front lawn, the thick black iron gate, the busy road with cars constantly clattering back and forth, and the bright pink Bougainvillea climbing up the silver chain-link fence which divided the property from the street. That division always felt symbolic of my mother’s great need to protect us from real life, the nasty world which lay in wait beyond its safe borders.

But back to the living room. I remember the pool-table-chalk-blue furry carpet. The two white couches. The glass French doors overlooking the backyard. The cupboards and shelves on one side with a silver saxophone and records and the sound system and photos of smiling family members. The old cemented brick hallway and three steps casually leading down to the blue carpet. And, by the black leather easy chair, Mom’s book collection.

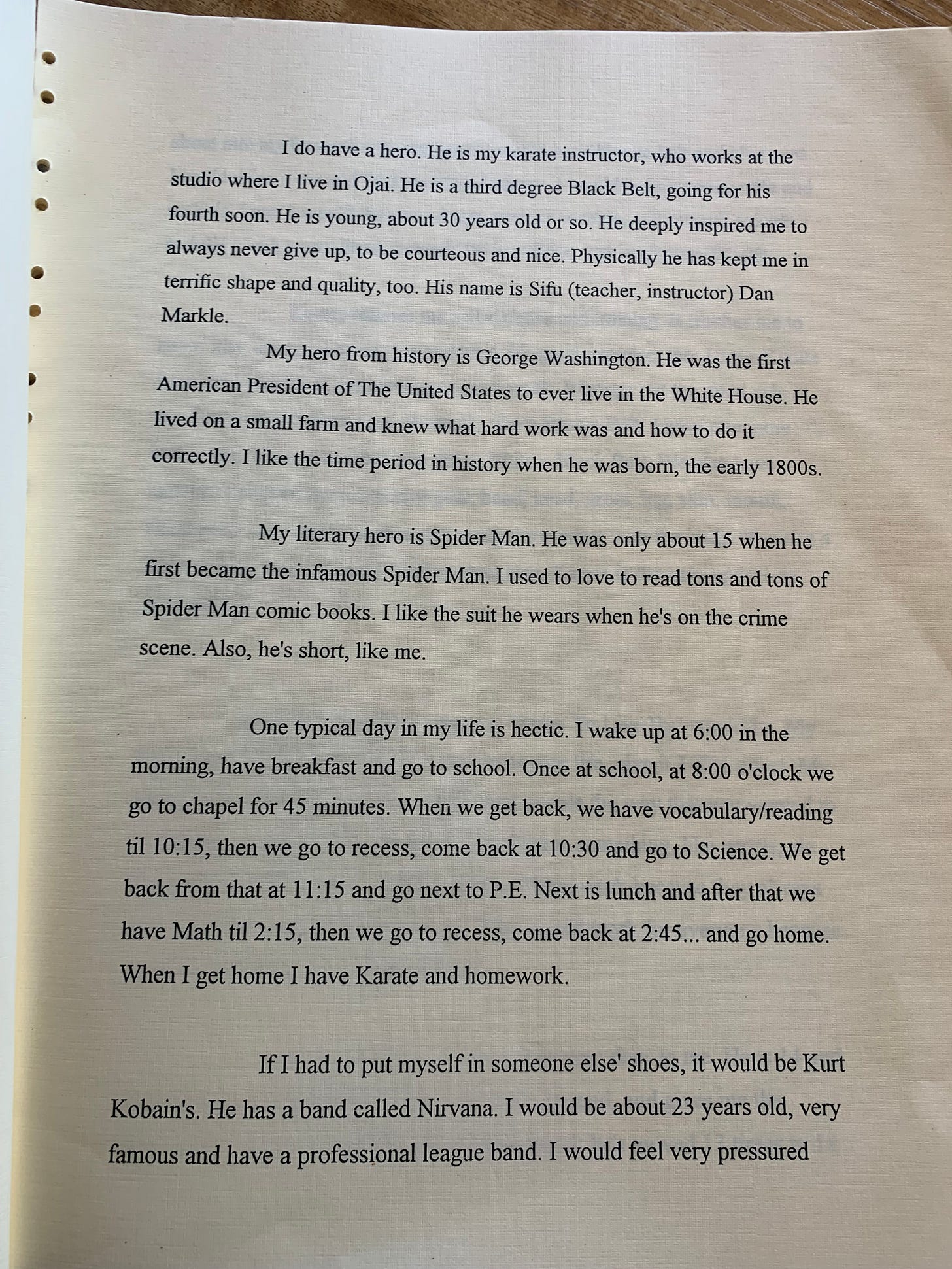

“My hero from history is George Washington. He was the first American president of the United States to ever live in the White House. He lived on a small farm and knew what hard work was and how to do it correctly. I like the time period in history when he was born, the early 1800s.”

*(Re the above G.W. quote of mine from age 12: He did not live in the White House; that did not happen until 1800, when John Adams lived there. G.W. was not born in “the early 1800s” but rather in 1732. In addition he did not live on a “small farm” but a very large one, and though he did know how to work hard, he also had slaves who did the brunt of the real work.)

You had to sit down to really look. The shelves were only perhaps four feet high. Low. But filled with books. F. Scott Fitzgerald. Hemingway. Flannery O’Connor. Faulkner. Stephen Crane. Steinbeck. Chekhov. Tolstoy. Dostoevsky. The books were mostly thick, with that musty stink I learned to crave, and heavy. Old. Dog-eared. I remember plucking a random book off the shelf, often, and opening it and just reading the sentences. Three-quarters of the time I had little or no clue what the hell it was talking about or what was happening. But I recall loving the sound of the words, the language, the syntax, the grammar, not that I knew any of those concepts in any real way back then. I just felt it. And sometimes I did grasp what was going on, at least in a basic way, and I’d get caught up in the story. That happened for me with Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago.

Mom read some of these books to me at night, she on one couch and me on the other, Dad asleep in the bedroom down the brick hallway, darkness around us, the stars bright outside of the glass French doors, Mom reading by one single beam of light from a nearby tall lamp. When she read I could sit back, relax, close my eyes and truly see the people, the characters, the settings, could envision the world being created. I imagined these worlds as real places, and wanted to meet these characters who seemed authentic to me. They must, I thought, exist somewhere, they couldn’t completely be made up and unreal, straight from the author’s wild, lush imagination.

By the time I reached eight or nine I’d already written a fair number of poems. Bad, silly, fun little ditties. About flowers, waves, people, school, animals, myself. And even stories a little later, random tales about shipwrecks and survival and other planets. Memoir, too. Even though the writing is childish—how could it not be?—it shows a basic talent, voice, and understanding of plot. Even then.

Sometime around age 11 or 12, I’d guess, I started reading Brian Jacques’s Redwall Series, about a kingdom of mice. Despite the fact that at that age I was really into skateboarding, surfing, BMX, Karate and drumming, I would sometimes nevertheless spend whole weekends plowing through book after book in the Redwall series. I couldn’t stop. It was like a drug. My parents seemed a little worried some moments, and would gently encourage me to go outside and “do things.” Sometimes I did, sometimes not.

High school, as I alluded, was a strange, explosive time. Other than school assignments, I don’t recall ever doing any actual creative writing during these four years. I was gaining life experience. My high school years were not average, by any means; they involved blackout drinking, anarchic punk rock shows in LA, parentless homes in Oxnard, serious drugs, intense rebellion, breaking many laws, encountering police fairly often, and finally getting expelled from school three weeks prior to senior graduation for pot and booze. It was, to say the least, a time of severe grim rage and joy.

And yet, despite the wildness of those years, and despite the non-writing, I did read outside of classes. The two guys who pulled me into the punk rock world—I didn’t need much convincing; the pump had long before been primed to the max—gave me what might be called “reading assignments,” what might be referred to as Serious Books One Must Read to Grasp the Importance of Rebellion. Books such as: 1984; A Brave New World; We Got the Neutron Bomb: The Untold History of LA Punk; Please Kill Me, NYC’s response to said previous book; Fahrenheit 451; The Catcher in the Rye; etc. (They also explained music theory, postulating that Johnny Cash and then Jim Morrison were really “the first true punk rockers.” See my post on my personal music history for more in this vein.)

It's funny and ironic looking back on some of my childhood autobiographical writings—stuff mostly around the ages of 11 and 12, 1994 and 1995 respectively—due in particular to the inherent darkness of it. Because that darkness has been a pivotal aspect of my writing ever since, and still very much is to this day, as anyone who reads my Substack knows.

Here's a quote from my Autobiography circa age 12, 1995 (again, I left all the spelling errors and syntax/grammar as is):

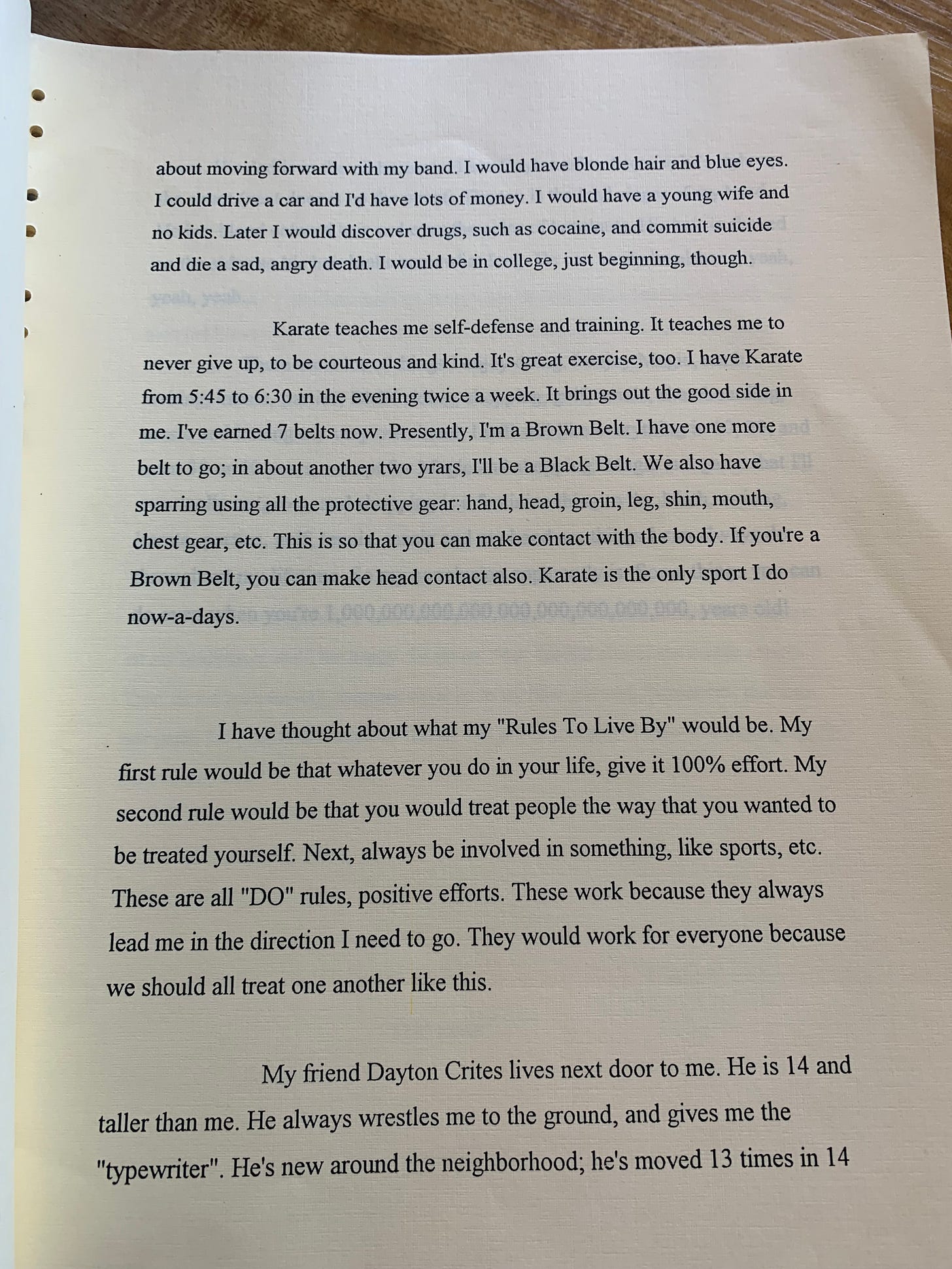

“If I had to put myself in someone else’s shoes, it would be Kurt Kobain’s. He has a band called Nirvana. I would be about 23 years old, very famous and have a professional league band. I would feel very pressured about moving forward with my band. I would have blonde hair and blue eyes. I could drive a car and I’d have lots of money. I would have a young wife and no kids. Later I would discover drugs, such as cocaine, and commit suicide and die a sad, angry death. I would be in college, just beginning, though.”

Wow, right??! That second-to-last sentence especially shows you how dark I could be, even that young. (It’s also fairly darkly funny.) Thinking back, I suspect I felt a darkness within me from a very early age, maybe as young as five or six, even. (That’s a whole other story.) So it wasn’t that “something happened” later in my life: Those feelings were already there, perhaps intrinsic to my very nature.

In my very early twenties I remember reading some books, but it was stilted and clunky; back then I was moving constantly from city to city, blacking out from alcohol often, and constantly moving from job to job as I frequently quit or was fired. Certainly two facts stand out from this time, though: At 22, living in Pacific Beach in San Diego I read Jack Kerouac’s On the Road for the first time, and it literally changed my life. It made me sell my few possessions and, when my lease was up, hitchhike around the Pacific Northwest and California. This became a five year on and off love affair with the road, thumbing, driving, Amtrak.

The second thing is that, in 2006—age 23—I started writing a regular journal. This was when my first adult recollection of The Darkness pierces the old light of my memory. I started once more penning poems, some of which I had published in little magazines seven, eight years later. I tried my immature, inexperienced, untried hand at short stories. I enjoyed the process; I recall coming home some nights, drunk, listening to The End by The Doors, and writing feverishly in my little leatherbound journal. Life, I dramatically thought back then, was so unfair and painful.

In 2008—age 25—now living in Ocean Beach, the Sunset District, San Francisco, I began what became my first novel, about my lurid high school years. I didn’t yet know it would be categorized as “Young Adult” literary fiction. I did not yet know anything about literary agents or the publishing industry, query letters or synopses, etc. All I grasped was that in order to publish a book you first had to write one.

On September 24th, 2010, at age 27, I hit a spiritual bottom and got sober. I haven’t had a single drink since. That was just shy of 13 years ago. I’m now 40. Immediately—now at this point living in Portland, Oregon—I finished the first rough draft of the high school autobiographical novel, full of anger and violence and darkness and also joy and aliveness and energy.

Over the course of many years—between say 2010 and 2017—I wrote a dozen novels; I polished, edited and pitched to agents my precious YA novel (and always got rejected, yet got very, very close a few times; read my piece about that here); I had about 15 short stories published in little literary magazines; I went back to college and got my BA degree in creative writing; I interned for nine months for a literary agent; I started a blog and website about writing and agents and editing; I began my book editing business; etc. In short, I finally became what I always deep down inside suspected: I became a writer.

That sense of historical and personal insight; that darkness; that arrogant yet needy voice all followed me from childhood into adulthood. It’s still there in my writing now, and it will probably always be there. Some things in life we shuck off, like a shell; others, we simply tuck away inside our psyches and carry on, not always knowing that we unconsciously continue their path.

Now, of course, I write on Substack. Some of my writing is fiction, some memoir, some personal essay, some straight nonfiction essay about politics, culture, other people, other writers, book reviews, etc.

“My literary hero is Spider Man. He was only about 15 when he first became the infamous Spider Man. I used to love to read tons and tons of Spider Man comic books. I like the suit he wears when he’s on the crime scene. Also, he’s short, like me.”

I didn’t need an MFA program to “teach” me to be a writer. (I don’t think you can “learn” to be a writer anyway; either you are one or you aren’t, though certainly you can expand on that innate talent if it’s already present within you.) I felt it nearly from the moment of first awareness. Being a writer is more of a feeling, an awareness, a sensibility, than it is physically writing. Though of course there is also that inherent, almost sexual need to write, which almost all writers in my experience seem to possess.

Being a writer, as David Foster Wallace once expounded in the 90s on an NPR interview with Terry Gross, means being deeply sensitive, wildly self-conscious, profoundly self- and other-aware, attuned to the voices and ideas of other people around you, being a sincere, deep, thoughtful speaker and listener, being someone who can grasp the depth, meaning and value of every single second. Writers are writers because they possess almost what might be called a sixth sense, a spiritual sense which allows them to see and hear and feel that which most people, the average person, cannot.

In many ways writers are frequently absurd, asinine human beings: Often too soft for “real life.” Too sensitive. Bruised easily. Non-practical. Useless at fixing an engine, say, or cleaning up a yard’s plants. (I’m obviously wildly overgeneralizing here, but, overall, I think there’s much truth here, though as with everything in life you have to treat people as unique individuals and take things on a case-by-case basis.) Rousseau mentions repeatedly in his memoir, Confessions, which I wrote about on a post recently, that he was viewed as stupid, unintelligent, and a reject by many men when he was younger, and even much later when he was just starting to publish his books. (For those of you born in a barn Rousseau was a thinker, philosopher and novelist who may have had the biggest impact on the rise of republics and the takedown of monarchies than anyone else in the 18th century.)

I, too, have had this stark, startling experience. Once, when I was 25, living in San Francisco in 2008, I was fired by a pizza restaurant for, in effect, being a dumbass. I was too slow. I dropped things a few times. The final straw: I somehow lost my little notepad in which I wrote down dinner orders. They canned me. I’ll never forget the look of shocking indignation on the face of the manager as she told me to go home and not return. The phrase, What the fuck is wrong with you? Seemed just on the cusp of her lips. She wanted to shake her head, I could tell, but somehow she barely restrained herself. She probably thought I was the dumbest person she’d ever met. I pictured her telling her co-employees and friends at parties for months afterward. And yet: I’d written a novel. I read books by Kant and Voltaire. I studied the classics.

“I do have a hero. He is my karate instructor, who works at the studio where I live in Ojai. He is a third degree Black Belt, going for his fourth soon. He is young, about 30 years old or so. He deeply inspired me to always never give up, to be courteous and nice. Physically he has kept me in terrific shape and quality, too. His name is Sifu (teacher, instructor) Dan Markle.”

With all of this, my point I think is as follows: Everybody has strengths and weaknesses. Some people are street-smart. Some people are talented when it comes to business or finances or politics. Some people have a strong work-ethic and they can work any job. Some are highly successful and make millions. For some, tech or the stock market is the thing. For still others blue collar physical jobs are it. And then there are writers, those weird freaks—outsiders—whose job it is to observe and write things down, to report and record the human comedy. We listen to your conversations. We watch your behavior. We laugh at our own fallacies, hypocrisy and contradictions. We try, as best we can, to put it all down with language in a manner in which a lot of people can comprehend what we’re trying to see. Our job is to communicate who we are, who you are, who I am, what it is.

This is not an easy task. I think it usually starts as young as first consciousness. Not with the physical aspect of actually writing, but with the inner aspect of first being aware, first grasping that human beings are strange creatures, first understanding ourselves on some level as being alien, different, “other than” the strange creatures around us. Most people don’t care much about clear communication, or about what words actually mean and what their Latinate root is, or about why someone acts, speaks or behaves the way they do. Most people are content to just “be.”

But not writers. We’re ever-curious; ever anxious; ever needy. We need to know what we’re working with here, what this whole “life” thing is all about. And because we’ll never know for sure in any concrete, exact way, we keep on writing, hoping against hope that somehow, some way, we’ll discover some Ultimate Truth that will save us from death, at least symbolically.

“I have thought about what my ‘Rules To Live By’ would be. My first rule would be that whatever you do in your life, give it 100% effort. My second rule would be that you would treat people the way you want to be treated yourself. Next, always be involved in something, like sports, etc. These are all ‘DO’ rules, positive efforts. These work because they always lead me in the direction I need to go. They would work for everyone because we should all treat one another like this.”