Adolf Hitler

What Trump is Not

When things are bad, economically, socially, demagogues rise. When things are bad, populism leads. When the two political sides are in extreme culture war, division and polarization only increase. The Left and Right were in fierce cultural and political battles in the 1920s and early 1930s in Germany. Look what the result was. Offer citizens something. Hitler was a consummate liar; he lied more than any other leader probably in all of history. He was Orwellian to the core. In his mind: He was helping the Jews. He had wanted nothing more than no war; Britain and France had attacked him. He was a savior of the German people. He had sacrificed everything, especially his personal life, for his people, his Aryan brothers and sisters. He was a fount of moral goodness.

All of these were of course dirty, worm-slithering lies. Hitler was a psychopathic madman who cared not one bit about the German people, or about the Jews. In the end he tried to destroy them both.

*This is a lengthy piece, at over 6,000 words. It’s an in-depth (but general and definitely not exhaustive) look at Hitler both personally and politically. To read the full essay please start a paid subscription for $35/year or $5/month. Enjoy.

~

I recently read the absolutely fascinating, horrifically terrifying 1973 classic by Robert Payne, The Life and Death of Adolf Hitler. I found the book while browsing in a local Lompoc bookstore, using half of my $100 birthday gift certificate. (I also purchased a biography of Marilyn Monroe, poetry by W.B. Yeats and Dylan Thomas, the concentration-camp memoir Night by Elie Wiesel, The Iliad and Dante’s Inferno.) It’s a lovely, used bookstore and I chose the books at random.

Like many people, I’ve always been fascinated by the 20th century phenomenon of Naziism. What was it? How did it arise? Who, really, was Hitler? It’s easy to look at a psychopathic mass-murderer like Hitler and simply decide that he was insane and horrific—both true—and to leave it at there.

And yet, if we look away from the terror I fear we risk making the same choices again. By “we” I mean western civilization broadly. I tell you one thing: Trump—who I do not support in any way, shape or form—is NOT Hitler. There is a vast, impossible chasm between these two men, and conflating them is dangerous, ahistorical and foolish. Believe me: You cannot read the story of Hitler’s rise to power, and his megalomaniacal, self-righteous insane rage, and compare him to a run-of-the-mill malignant narcissist like Trump. Trump cares about Trump. Hitler cared about destroying the world. And he nearly did.

*

It didn’t start that way. Born and raised in a small Austrian town in 1889, Hitler was of the lower middle-class. His father was a civil servant. He was very close with his mother, not with Dad. Beginning in childhood he seemed to be a strange mix of bright and stubborn, and like going against the grain. He was a natural rebel. He cherished reading. Much of his inner world—and he possessed a large inner world—was based in fantasy. But, at first, he seemed to be a more or less normal kid. He liked to draw. He liked to create stories in his head. In many ways he lived in a world of his own.

Everything changed when Hitler was about 10. His younger brother, Edmund, became sick with measles and died in 1900. This was a hard shock to the system. The whole family suffered. It was around this time that Adolf started acting out. Talking back in class. Mocking the teachers—he became locally famous for this throughout his school years—getting into minor trouble with friends, and, most crucially, pushing back against his irate, strict, rather authoritarian father.

His father felt his son should complete formal schooling and then join the civil service like himself. Hitler, however, by his pre-teens, had already decided his fate was to become an artist. His father fought bitterly about this. Hitler wanted to be taken out of his normal school—he was failing several classes, not because he was stupid but because he was resisting formal schooling; before Edmund’s death he’d generally achieved stellar grades—and placed in an art school. His father, Alois, refused.

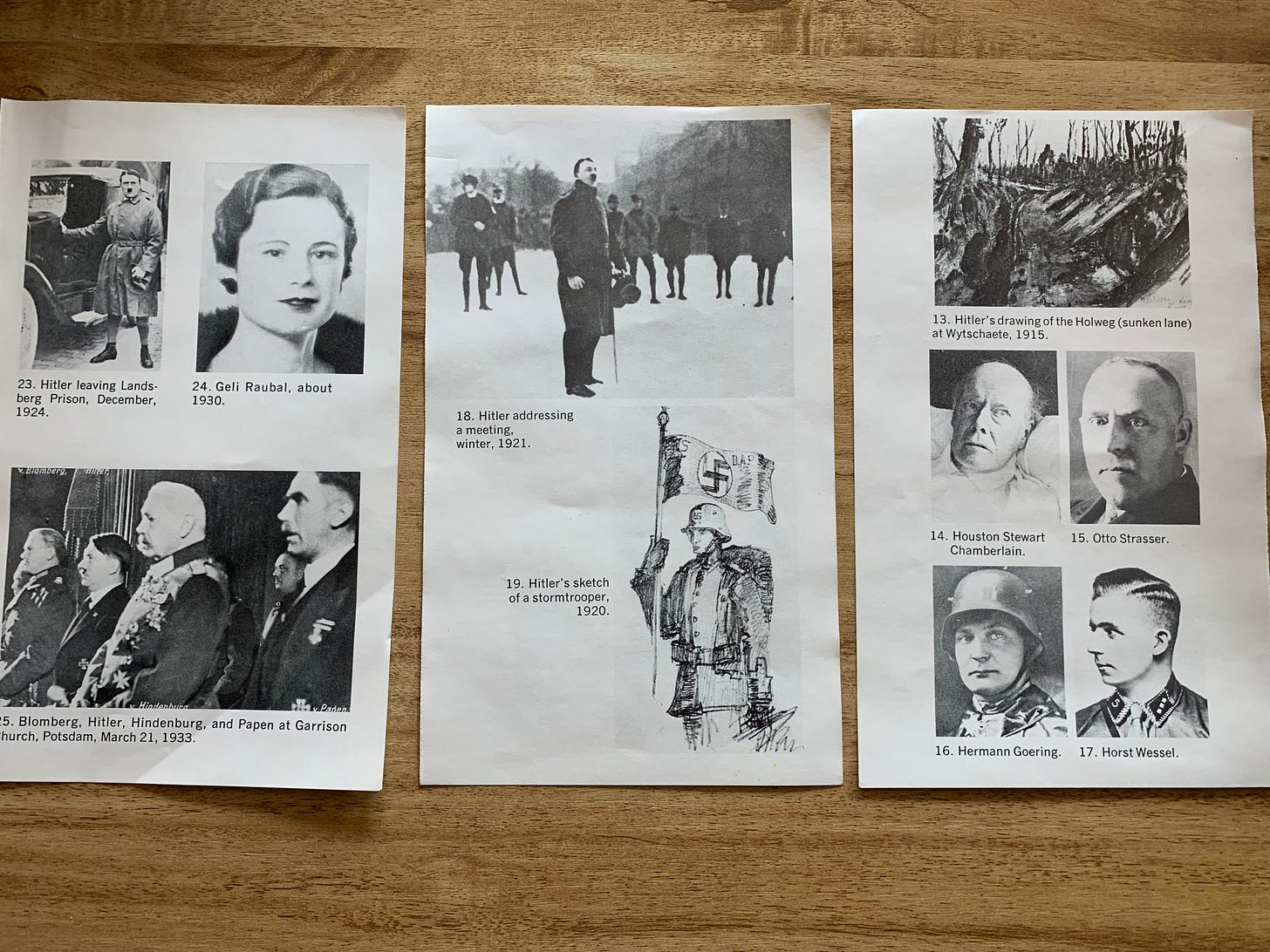

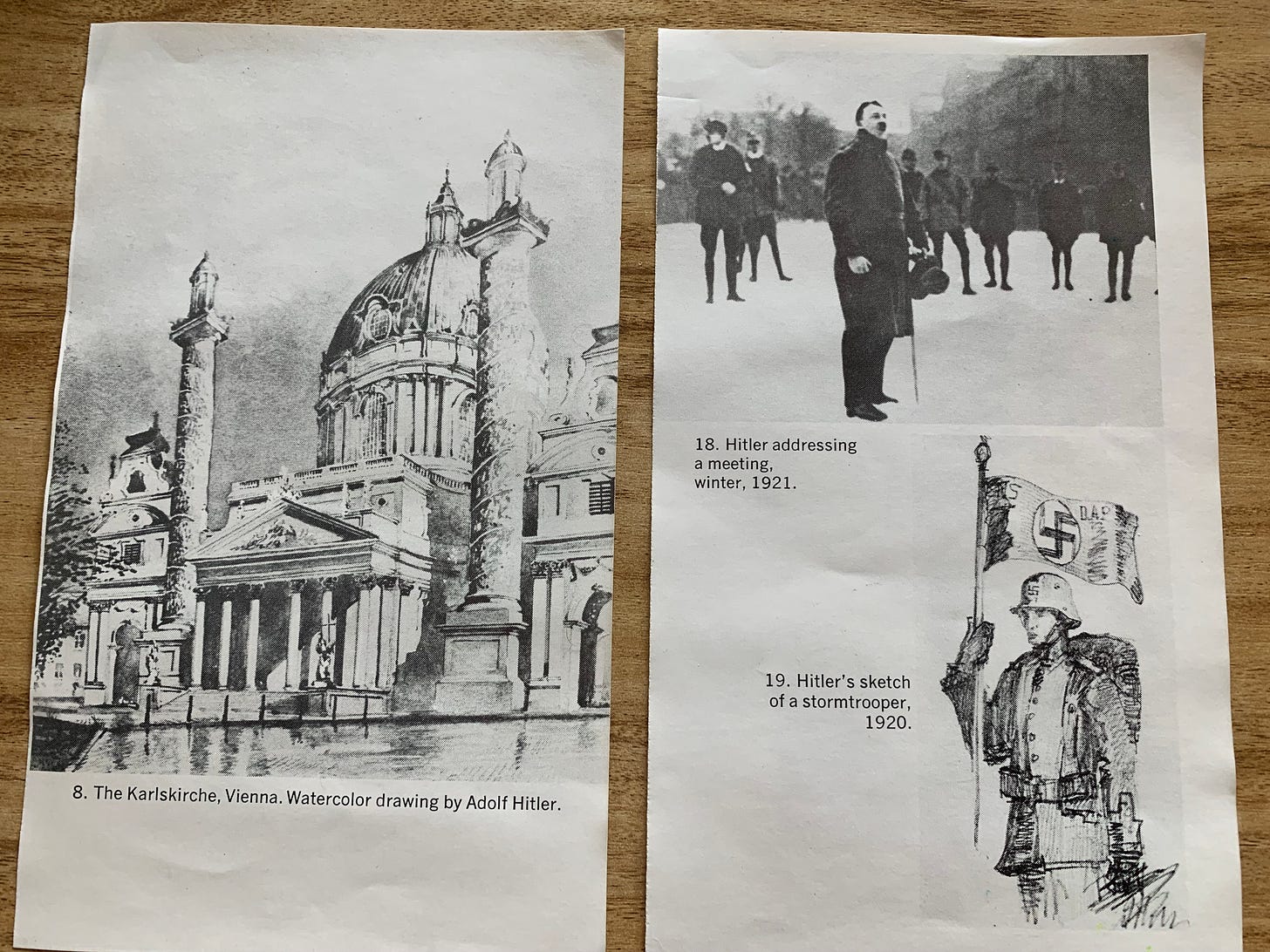

The shock from Edmund’s death still fresh in his system, his father suddenly died from a pleural hemorrhage in 1903, when Hitler was about 13. He’d never gotten along with his dad, resenting the authoritarian strictness of the old man. Accounts differ as to whether physical abuse was going on, but this book, which interviewed friends and survivors, claims that he most likely was not physically abused by his father. And yet yelling, troubling levels of dictatorial control, and hard-drinking were part of his father’s repertoire. Despite their issues, the 14-year-old Hitler was plunged even further into the sordid isolation of his reading and deep, rich inner world. He focused on art. He became obsessed with going to art school in Vienna. He had few friends and he lived mostly in fantasy. Reading occupied much of his time. At this period he was not yet antisemitic. He frequently drew pictures, especially of buildings and structures. He possessed an eye for architectural design.

Around 1905 or 1906 Hitler’s mother, Klara, was diagnosed with cancer. Hitler truly loved his mother and was devoted to her. She’d been a domestic servant and maid for a long time. She received some inheritance and a pension, plus the house her husband had purchased after his death. She loved her son intensely. While she grew sicker, Hitler stayed loyally by her side. He took care of her. The doctor who came to their home frequently and did everything in his power to help her, was Jewish. When she finally succumbed to the cancer—and the toxic treatment—and died in 1907 (Hitler was about 18) the young, intense man profusely thanked the Jewish Austrian doctor. Hitler’s mother was only 47.

*

So at this point Hitler is 18, and he’s lost his younger brother and both his parents. His dream was still to go to art school in Vienna. He had one friend, who listened to Hitler’s long, hardcore raging rants about people, life, art, history, politics and society. His friend—Kubizek—followed him everywhere. They spent endless hours together, wandering around the town and talking. Hitler received a small inheritance and a pension in the form of a monthly amount. Strictly-speaking, he didn’t have to work. He wasn’t rich, by any means. But he wasn’t poor. He essentially had a passive-income.

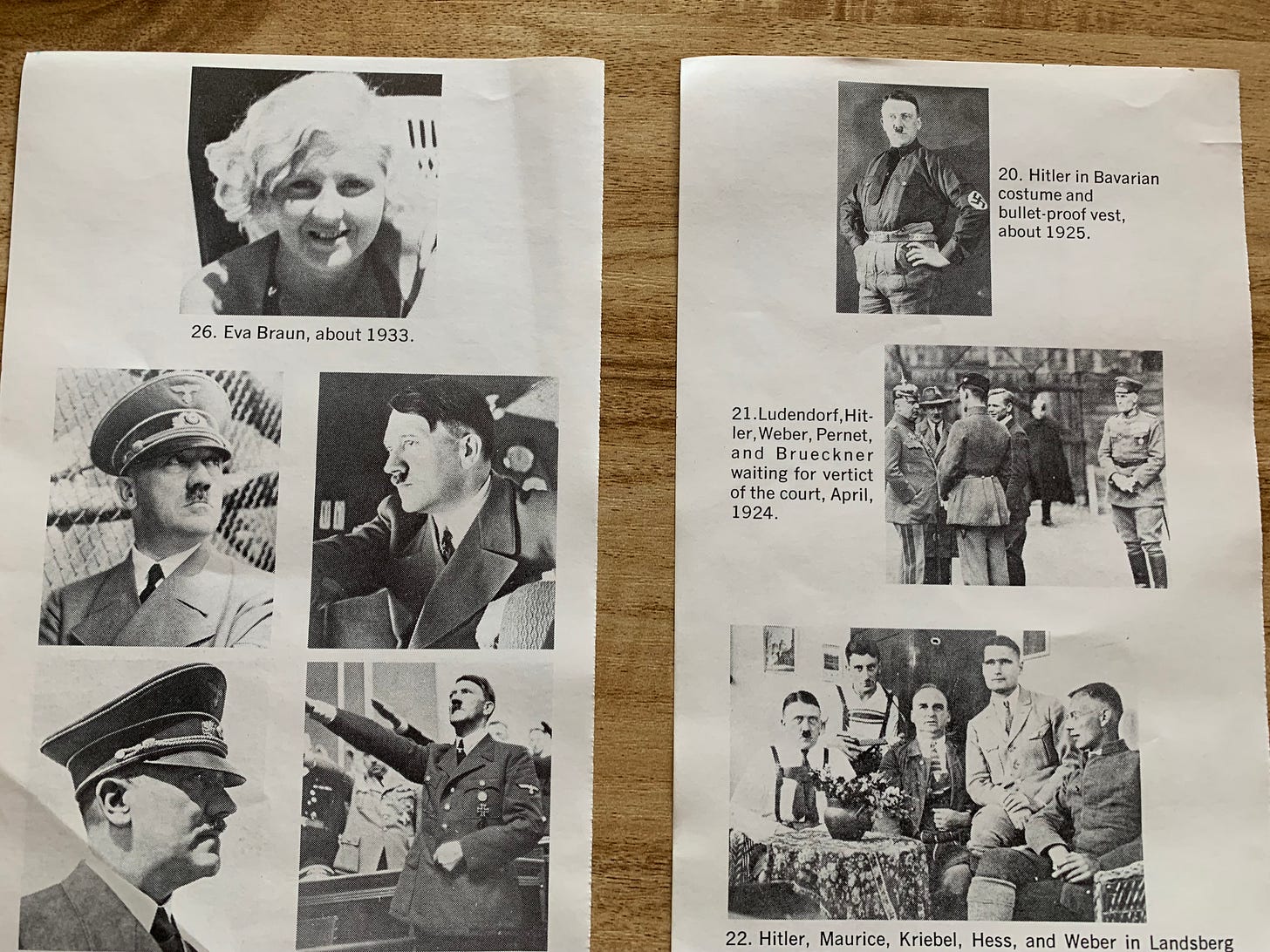

This was the period when he rented a tiny, prison-like room in Vienna and tried to get into art school. In the book I read there are half a dozen drawings and watercolors and paintings done by Hitler over his lifetime. While not a Picasso or Cezanne or Renoir, the man did have some talent. Especially when it came to architectural drawings. Yet, when he took the art school examinations, including examples of various pieces of art, he failed. When he tried to take the test a second time, he was denied even the ability to take the test.

During his time in Vienna—his buddy Kubizek, a pianist by then, moved in with him—Hitler went through several metamorphoses. For one, he actually did begin to make a living doing his art. Maybe not in the way he’d planned or hoped. He sold postcards with his drawings and paintings on them, and he started to do fairly well. He was living, at one point, in a poor-house for men. For a very low fee, men who were close to poverty could live in the house as long as they were actively searching for work. He’d bungled his inheritance and there was a mix-up around the monthly pension he was receiving and so, for a little while, he had little income.

Prior to this, he’d actually been “on the streets.” He’d literally run out of money and had, in the freezing Vienna winter, slept on benches and in bus stops, eventually staying for a while in a homeless shelter. It was here that he met a man who told him about the poor men’s house. This man also, for a while, became Hitler's “art agent,” helping to sell his painted postcards, taking a small fee. He ended up living in the men’s house for several years. He frequently sold postcards to Jewish retailers.

It makes one wonder: What would have happened if Hitler had gotten into art school? Would we be contemplating Adolf Hitler the 20th century eccentric artist instead of the totalitarian dictator who almost destroyed humankind?

Maybe.

*

Hitler drifted for a while. He showed up at his half-brother’s house in Liverpool, crashing on he and his wife’s couch for several months, recuperating from his exhausting, impoverished lifestyle. Later he ended up in Bavaria, southern Germany. When World War I started, in 1914, he pleaded with Emperor Wilhelm II to be allowed to join the military and fight for Germany. This was granted. Hitler was 25 years old, “old” in terms of the average soldier. Choosing to go to war was easy for Hitler: He had no sense of self still; his dreams of being an artist had more or less dissolved inside the acid of harsh reality; and he had zero direction. The military would give him an angle, discipline him, and open him up to camaraderie and friendship.

For four years, throughout the entirety of the war, Hitler fought bravely for the Germans. He was a dispatch runner, meaning that he faced a constant hail of deadly bullets sprinting across open fields and open areas in order to deliver crucial messages from one regiment and captain to another. He faced constant danger. He was wounded twice, once which included blinding him for about a week. Twice he ended up in the hospital; both times he went back out into battle afterwards. He was daring and courageous. He received many military awards, including the famed Iron Cross.

For roughly two years after the war—1918 to 1920—he technically still worked for the military. He was given the military intelligence job of infiltrating the nascent German Workers’ Party (DAP).

Never a particularly political person—though a fairly well-read one in terms of politics and history—he’d by this time, in his late twenties, very early thirties, become an antisemite. (He also gorged on books engulfed in conspiracy theories.) This was not shocking because, disgustingly and tragically, antisemitism was pretty accepted and normal at that time, not only in Germany but in Europe in general, as well as the United States and most of the globe. Not everyone was an antisemite, of course, but it wasn’t outside of the window of normality. It stayed inside the Overton Window.

Hitler had always been a strange mix of inner contradictions. He railed against Jews and yet sold his picture postcards to Jews and had some Jewish friends. Even the first woman he obsessed over was Jewish. (They never dated and hardly ever even met.) He read books voraciously yet loathed formal education and teachers especially. He had a certain sophisticated refinement—he loved, for example, attending the opera and did it often (his favorite was Richard Wagner, a genius and blatant antisemite)—and yet he also had a sort of rebel feral streak inside himself which smacked of the anti-intellectual conspiracy-theory type.

He both believed firmly in facts and yet often made things up whole cloth when trying to make a point. He could be calm sometimes and raging and insane at others. His rages were notorious to people close to him at this time.

Strangely, he could condemn philosophy and then go read Schopenhauer. (Schopenhauer and Nietzsche had a big influence on Hitler’s notions of the “will to power.”) Hitler began to see himself during this period not so much as an artist anymore as a sort of “Superman” who would inevitably rise up from nothing and punch German’s enemies in the face until they cried uncle. Many of his influences had convinced him that both Germany and “Aryans” (the mythical white tall blue-eyed blond Nordic race of people) were destined for greatness and global rule.

*

At this time some people were talking about the infamous “stab in the back,” the idea that “the Jews” had screwed over Germany and thus had caused the nation’s loss in the war. The famous, brutal Treaty of Versailles, signed in 1919, had crippled Germany with harsh, unreasonable reparations ($33 billion gold marks), sliced off their military power, and significantly weakened Germany. Sections of Germany had been cut off of the map, such as Poland, Czechoslovakia and Austria. All in all Germany lost about 13% of it’s territory. The nation had been humiliated.

Many Germans were angry. The king had fled. The country now had a parliamentary democracy. Inflation was out of control, as was unemployment. People felt despondent. Many developed the theory that the Jews were to blame, that corporate capitalist greedy race of people who supposedly pulled the global puppet strings. The idea was that Germany had not so much lost on the battlefield but had been undermined by Jews and Bolshevists at home by these groups’ creation of labor unrest and fomentation.

The loss of World War II had led to the abdication of the emperor and the democratic rise of government (the so-called Weimar Republic) and the dissolution of the Hohenzollern empire. (Also it’s important to remember that in Russia, 1917 had brought the Bolshevist Revolution to power.) Hitler hated two groups more than any other: Jews and Communists. He also severely distrusted and disliked democracy. He saw the United States as a joke.

Germany began doing better around the mid-1920s due to the Dawes Plan, which involved the United States giving out massive loans to Germany to help them pay off their French and British landlords.

Starting around 1919, after attending a German Workers’ Party meeting—at the time it was an unknown nascent party with only a dozen or so members—Hitler discovered, to his own shock, that he possessed strong public speaking skills. (He’d first learned this while speaking to a cluster of men at the men’s poor house but hadn’t thought much of it at the time.) He’d argued with some of the speakers from his chair a few times and then finally spoke up at the podium. The result was dramatic. He had a way of half screaming, of using his voice as a battering ram, of exploding into mad, wild frenzies of dramatic anger, of lifting the crowd up along with him, taking them along for a ride, of gesturing with his hands as if they were swinging scythes. He felt like an orchestra conductor, as if he were his hero Wagner. He used antisemitism, storytelling, politics and myth to create a sense of urgency.

Soon he was speaking constantly, rising fast and far above any of the other speakers. The number of German Workers’ Party members began to soar. People came to watch Hitler speak. His name became synonymous with power. Over time, he began to become indispensable to the party. He finally superseded the founding members and simply became the leader of the party, de facto. When the founders complained, Hitler threatened to leave the party. They reneged. He had the party in the palm of his hands. The party essentially was Hitler.

The ideology of the party was confused. There was a smear of pseudo working-class ideology, and pro-socialism ideas…but these were mostly just fluff. Underneath it all lay the real foundation: Antisemitism and Hitler himself. In this manner we can say Trump is similar: Both ravaged their respective party, did away with it, and made it themselves. Trump is not a Republican; Hitler was not a German Worker party member. It’s the Party of Trump and it was the Party of Hitler. He sought total, absolute power. It was never really about workers or socialism, though Hitler did early on claim to want to protect women and poor families, saying the government should never allow women to fall into depravity or prostitution, and that all families should be able to survive socioeconomically in society and that the government should guarantee this. He also felt wages should be guaranteed for workers.

As far as women personally, Hitler was strange. Much has been made about the myth that Hitler—and many of his nefarious cronies in the third Reich—were closeted homosexuals. The idea goes that it was largely their sterilized, repressed homosexuality that they projected outward as rage towards the world. Perhaps. It’s true that Hitler slept with and dated very few women. Much of his “liaisons” were actually fantasies in his tortured, indefatigable mind.

There was, of course, the 23 years younger Eva Braun, who he officially married and died with in 1945 and who he’d been seeing on and off for many years. There was also his much younger half-niece, Geli Raubal, who he slept with, lived with, and ultimately drove to suicide. More likely, I think he was simply either asexual or just not interested very much in sex. Sex, for Hitler, was power. Anything less than that—let alone a weak and trembling female—was absurd. (In his warped, twisted mind.)

Nevertheless, the man was often alone for much of his life, or else with a friend or two, until he discovered the German Workers’ Party.

*

In 1923 Hitler and his growing entourage tried a serious revolutionary Putsch. Since 1919 he’d slowly been gaining not only a reputation but also a gaggle of intense criminals he used as security guards. He also began developing his SS forces, essentially a criminal-citizen [unofficial] army. In 1923 his plan was to overtake the Bavarian government—he used a gun and threatened high German authorities and other leaders—and then for his army to march on Berlin, taking over the Friedrich Ebert democratic government. He predictably failed. A dozen or so people, mostly on his side, were shot and killed in the street-fighting to restore order.

He ended up on trial. The trial was a joke. The party had friends in the justice system. Therefore, he got off easy. Incredibly, he wasn’t sent back to Austria. For years Austria had been seeking him in order to extradite him back to his home country to serve his mandatory time in the military, which he’d skipped. However, he had fought bravely for Germany for all four years of the war. That counted.

Hitler was given a five year stretch in Landsberg Prison in 1924 which ended up being nine months. It was a cake-walk. The Putsch had made Hitler famous; he’d become a national figure. He was known and mostly praised and respected, even by the guards and leadership in the prison. Therefore he was treated like a princely mob boss inside, allowed to see people he wanted to see, do things most other prisoners couldn’t, write as much as he wanted, have plush dinners with fine dining furniture, you name it. His nine months were a joke. He enjoyed this time. And he wrote a book.

He mostly dictated his book, Mein Kampf (My Struggle). It covered his biography up to that point, his path to power in the German Workers’ party, the Putsch, his raging antisemitism, and his life and ideas more broadly. A fellow member—several had been sent to Landsberg alongside Hitler, including Rudolph Hess—typed the manuscript for him as he dictated. It was later published and did fairly well at first, selling just under 10,000 copies, but quickly sales fell until he rose to power as chancellor in 1933.

*

When Hitler was released he was more popular than ever. The German Workers’ Party had been restricted by the German government, but only until 1925. This did not matter, of course, because the name was irrelevant; the party was Hitler. Soon he started speaking again. He kicked out certain members he didn’t like or didn’t trust. (Hitler had very low trust in people.) He formed a tried and true inner circle of more or less trusted confidants. The party had changed its name to the NAZI party, National Socialist German Workers’ Party. Hitler cared in reality nothing about socialism or about workers or the working-class anymore. Make no mistake: The NAZI party was about one thing: Hitler’s total power. The party itself was a shell which was filled up with Hitler’s complete control.

In the mid-twenties the Dawes Plan occurred, mentioned before, wherein the United States gave out gigantic loans to the German government and corporations to pay off their abominable French and British reparations payments. Things looked good. Hitler was frustrated and wanted the economy to tank and for things to get worse for Germany so that he could have an excuse to exercise his power. When things were too good there was little chance of a populist dictator like him rising above the fray.

People didn’t care as much about the “stab in the back” or about the Jews and Communists when unemployment was down, inflation had stabilized, and people were making money. Hitler bided his time, speaking to bigger and bigger crowds, gaining more and more followers, and building up his SS terror forces. They engaged in crime often. He met people like Goebbels and Himmler. They were evil, sick cretins, criminals who would do anything to grab on to Hitler’s growing coattails.

*

Hitler got what he wanted in October,1929. The famous Black Tuesday stock market crash in Wall Street reverberated across the world. Everyone was affected. Since the U.S. had been granting massive loans to the Germans to pay back their loans, when America suddenly stopped being able to offer these loans, Germany fell into economic depression and chaos. They couldn’t pay back either the reparations or the loans. They were in a quagmire.

This allowed Hitler to rise. He was 39, 40 years old by this point. Hindenburg had taken power as president in the Republic in 1925. As the 1930s began and the Depression deepened, things grew worse in Germany; more and more people were susceptible to Hitler’s antisemitic, paranoid, mythical, non-fact-based conspiracy-theory rages. The problem, he assured his growing followers, was the Jews. The communists. He did not mention anything about murder or concentration camps at this point. Only “removal.” But he clearly wanted to rebuild Germany’s military; cease paying back the incredibly crippling reparations; and annex several countries (Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland) “back” into Germany.

This time, Hitler decided, he would go the legal route. He would use democracy to his advantage; he would leverage his power using conventional means. He ran in the 1932 election and won about 13.4 million votes. Hindenburg, however, grossed 19.3, beating Hitler handily by about 6 million votes. Because Hitler had come in second place, however, pressure was put on Hindenburg to select Hitler as the chancellor underneath him. Hindenburg—old and accommodating—refused, but offered Hitler the vice chancellorship. Hitler was outraged and said no. But many of the seats of power in the Reichstag had shifted to NAZI members. They had power. Thus, Hindenburg felt his hand had been forced and, in January, 1933, he assigned Hitler as the chancellor of Germany.

*

Hitler began basically mobilizing for war and organizing the military and the NAZI members into absolute power from the moment he came into office. Hindenburg was president, but that seemed more and more to be a frail paper-thin facade. Hitler more or less got whatever he wanted. In August, 1934, Hindenburg—86 years old—died. Immediately Hitler dissolved the presidency, canceled the Republican form of government, and proclaimed himself the autocratic leader of Germany. The “Fuhrer.”

By March of 1938 Germany had taken over (annexed) Austria, in what was called the “Anschluss.” Austria was unable to fight back. They were taken quickly and easily. This was the beginning of the lightning “Blitzkrieg” campaigns. Next it was the Sudetenland, then all of Czechoslovakia, and then Poland. (Poland bitterly fought back.) By 1939 the world was at war. The 1930s had seen the international rise of fascism: Franco in Spain; Mussolini in Italy; Hirohito in Japan; Stalin in Russia; Hitler in Germany. Hitler had helped Franco crush the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War. Germany, Russia, Italy and Japan would conquer the globe and divide it between them.

This was the time of “appeasement” by the British, the French and the Americans. They kept allowing Hitler to strike new nations, gobbling them up like stir-fry. Neville Chamberlain in the U.K. was notoriously foolish and accommodating, continually thinking Hitler possessed reason. He did not understand Hitler’s mind. Few people did. This was far before iPhones and the internet; the world was not connected in the way it is now; information traveled slowly and confusedly. Myths and rumors abounded. No one thought this no-name wild man who’d come out of nowhere would start a world war.

But he did.

*

I’m not going to describe World War II in lurid detail. That’s for the history books. We all know the basics: The British, French and Americans, alongside the Russians—in 1941 with Operation Barbarossa, Hitler went back on his non-aggression treaty with Stalin and attacked Russia; this was probably his biggest strategic mistake—fought valiantly (especially the Russians, who lost close to 25 million men and fought off the invading German hordes through several brutal Russian winters).

Germany, Italy and Japan lost the war. Two atom bombs were dropped on Japan, who finally relented. The period of dictators was over. The fallen nations were welcomed back into the global community and economy as democratic, capitalist states. The United States had entered the war in 1941 after Pearl harbor and was a major factor in defeating the evils of Hitlerian fascism. The Cold War with Russia (the U.S.S.R.) began immediately—even before the end of the war—which in some ways we’re still fighting even now. The war lasted six long ruthless years: 1939-1945.

During the war years—and to a lesser degree before the war—Hitler became a megalomaniacal psychopath. Perhaps he already was one, and it was only when he at last took full power that it showed in its complete form. He took on a sort of Christ complex, believing he was “divinely” empowered to rule the entire world. Jews in Germany and then in the new territories of Austria, Czechoslovakia, France and Poland were treated savagely, and slowly they began to be shipped to isolated concentration camps, some in Germany but most in Poland.

The plan at first had been for these torn, unfortunate Jews to work, but soon they became systematic death camps. Ethnic cleansing as never before seen. Huge pits were dug and Jews were shot and hurled into the pit. Some were dead, some still barely alive. The bodies rose as more were shot and thrown in. Whole families were forced to step, naked, down along some earth-dug stairs, into the pit, plodding onto the heads of the damned, and then they themselves were shot. Soon someone would be standing on their heads, etc.

Then the gas chambers arose, using shower-like faucets which actually let out diesel exhaust and, later, the famous Zyklon-B gas which killed Jews and others in the millions. Most of the bodies were burned. Jewelry was plucked from dead fingers. Gold was extracted from teeth after death. It was Mephistopheles on Earth. Total, absolute terror. A righteous dystopian novel happening in real, actual life. A complete horror show.

Hitler showed no empathy for the Jews or for Communists or his enemies. He did, however, become deeply emotionally damaged, depressed and suicidal (he became suicidal many times during his life) when his much younger half-niece who he’d at one time been living and sleeping with, killed herself when Hitler kept her hostage in an apartment, refusing to let her leave. This suicide stuck with him, and later, towards the end of the war, when Germany was getting its ass kicked by Russia in Stalingrad, he remarked many times that his troops didn’t even have the guts to, in the face of certain defeat, shoot themselves in the head rather than be taken by the Communist enemy. He compared their “weakness” to his niece’s courage. (Stalingrad was a disaster for Germany.)

His younger brother’s and his mother’s death, too, had a major emotional impact on Hitler. He experienced, spoke of and showed externally intense signs of obvious grief and sadness. He often suffered from depression, guilt and shame. He was deeply selective about what and who he cared about. Only certain things affected his emotional core. Without question, however, he was a sociopath and psychopath. And a megalomaniac. And suffered from paranoid self-delusions of grandeur. (These all became worse as the years ticked by. By the end, in 1945, he was completely insane.)

It's true that Hitler almost never got drunk. (He did drink beer fairly often.) It’s true that—with the small exception of Bavarian sausages—he was a vegetarian. It’s true that he loved dogs and had a wolfhound until his death. It’s true that he had a certain streak of genius and a certain kindness in him at various times. He comes off, to me, on the page, as an interesting mix of highly intelligent and profoundly stupid (in some areas), as well as 75% delusional most of the time. The best thing he ever did was shoot himself in the head in 1945 in his underground bunker in Berlin.

His last months were spent in said underground bunker in Berlin. He’d had many bunkers in many places, including different parts of Germany, Austria, Ukraine. “The Wolf’s Lair,” they called it (he and his top SS men), was in Poland. Goring, Goebbels, Himmler and others were beyond evil. They committed or ordered committed atrocious acts of rancid, nauseating violence at just a slight nod or grin from Hitler. Hitler called himself many names—the Fuhrer, among others—including one which he loved: Supreme Law Lord. He saw himself as God. Lord of the world. All he wanted was one thing: Everything. Anything less was unacceptable.

Incredibly, his followers became zombie automatons and did, with very few exceptions, Hitler’s every minute bidding, exactly how and when he ordered it. Hitler’s power is a lesson in group-think extraordinaire. When the Overton Window shifts, based on who’s in power, it’s truly amazing—shocking—how quickly people can create new social norms such as murder, rape, lying, and not bat an eye. As individuals, we think this is nuts. But as a group people act very differently. We see that now with social media and political tribalism. The “us” online is not the “us” individually in real life. Group-think taints people’s ability to think critically, or even to think at all. This was to Hitler’s dangerous advantage. Again, I see a small vestige of this on both political sides now, which is terrifying.

Hitler’s final months in the underground bunker in Berlin were insane, bizarre and tortured. A macabre dance of death. He was with Goebbels and his wife and six kids as well as other officers in the high command. As it became more and more clear that the war was coming to inevitable end, and that the Russians were going to overtake Berlin, Hitler decided that 1. Germans should destroy their own hallowed city, rather than give in to the Communist foe; and 2. Hitler would kill himself. He knew—certainly correctly—that if the Russians caught him alive it would be torturous beyond belief. He could not let that happen. The 33-year-old Eva Braun decided to marry Hitler and die with him.

Hitler in those final months wrote out a lengthy political testament, as well as a will. He gave away money—capitalist industrialists had lined his pockets since the 1920s—to his siblings and other family and people he cared for. Goring and Himmler, who Hitler felt had betrayed him by suing for peace with the Russians without his consent, he ravaged, gave nothing to, and “demoted,” which was purely symbolic by this point.

He said goodbye to his fellow friends and officers multiple times. Once, when he went into his private room in the bunker saying he was going to shoot himself at last, a big party began amongst the others, complete with dancing, alcohol and cheering. They thought Hitler was dead. He emerged, annoyed, telling them to keep it down. Caesar had not yet fallen.

Finally on April 30, 1945, the Russians very, very close, Hitler tested the cyanide poison on his dog to make sure it worked. It did. The dog died and then one of his men shot every single newborn puppy which had recently ben born. After that, Hitler told them he’d kill himself, with Eva, and that they should burn his body afterward. He and Eva locked themselves in the room. After a brief time his men checked on him, including Goebbels. Hitler was dead. He’d shot himself in the right temple using a wrapped towel to muffle the noise. Eva Braun had taken the cyanide. Within ten minutes their bodies were burning outside in the garden. Hitler had once more eluded responsibility. Goebbels and his wife and six children took the cyanide and all perished.

Berlin fell.

*

There are endless lessons one can take from Hitler’s unlikely rise to power. One is that, when in times of economic strife, populism tends to rise to the surface. We saw that with Trump in 2016. Trump is no Hitler. Nor is he a fascist. He is a narcissistic, megalomaniacal asshole, and he does have some “fascistic tendencies.” For example claiming the 2020 election was stolen when all the evidence was against him. Saying he wants to be president for life. He rose to power largely off the resentment of working-class uneducated white men who’d been getting screwed for generations now as a result of globalization, NAFTA, cheap exported labor, AI, the opium epidemic, immigration (to some degree), etc.

When a whole population gets gaslit and white working-class people are told they’re all a bunch of ignorant racists, and the economy is not what it once was and all the coal and mine and auto factory jobs are gone, and whole areas of cities have been demolished (Detroit, for example), anger makes perfect sense. When you add on to that a Democratic party with a new “Woke” smug attitude, dominated by a young, rich, white tiny media elite, and you shift away from the working classes and towards elitism and identity politics, yes, you’re going to get pushback. Running Hillary Clinton in 2016 was the Democratic Party’s first major mistake.

Many of the white working class counties who voted for Obama in 2008 and 2012 switched for Trump in 2016. Some 14% of Bernie Sanders primary voters switched for Trump in 2016. These numbers should tell you something important. People are angry; people feel left out of the economy and of progress; people feel alienated, disrespected and abandoned.

The Democratic Party has not listened to these voices. Covid did not help. The media lies and the racialism of virtually everything—making absolutely everything somehow about race—has only pushed these people, and many others, myself included, further away from the Democratic Party. Meanwhile you’ve got a more or less insane and Trump-mimetic Republican Party which is so absurd at this point that it’s literally like watching Broadway theatre. No wonder RFK Jr. is polling at 15%. Add in to the mix social media and disinformation, not to mention bias and echo chambers and violent tribalism, and we’ve got one hell of a problem.

I don’t know what’s going to happen in November, 2024. I worry very much about Trump. I worry very much about the fringe Left, too. Biden is old and unpopular. But one thing seems clear to me, after reading 600 pages about Hitler: If we want change—I mean really, actually want it—we’re going to have to get offline and start listening to each other. In real time, in real life, flesh to flesh. Screaming at the victims and calling them racist isn’t going to solve anything and in fact only makes things worse. Constantly reaching back into history—slavery, Jim Crow, redlining—isn’t going to fix our problems in 2024. Sure, there is a legacy of slavery, Jim Crow, redlining, etc. What can we do NOW?

If we don’t start dialoguing with one another, if we don’t start actually listening, if we don’t start rejecting tribalism and start using critical thinking skills, I’m afraid we’re likely doomed to repeat history. Because Trump may not be the worse one we’ve seen. Somewhere, there’s a candidate far nastier than Trump, someone much more Hitler-like, who could rise to unlikely power and, on the backs of the resentful working class masses who feel unheard, become the first true dictator of America. It’s possible, people. Trump isn’t that guy. But he may be opening up the door.

Democrats need to think long and hard about how they respond. Two wrongs, as we all know from history, do not make a right.

When things are bad, economically, socially, demagogues rise. When things are bad, populism leads. When the two political sides are in extreme culture war, division and polarization only increase. The Left and Right were in fierce cultural and political battles in the 1920s and early 1930s in Germany. Look what the result was. Offer citizens something. Hitler was a consummate liar; he lied more than any other leader probably in all of history. He was Orwellian to the core. In his mind: He was helping the Jews. He had wanted nothing more than no war; Britain and France had attacked him. He was a savior of the German people. He had sacrificed everything, especially his personal life, for his people, his Aryan brothers and sisters. He was a fount of moral goodness.

All of these were of course dirty, worm-slithering lies. Hitler was a psychopathic madman who cared not one bit about the German people, or about the Jews. In the end he tried to destroy them both.

We, too, will destroy ourselves if we don’t wake up and start talking with each other again.

Thank you for all the background information

and deep thought and analysis

you have offered us here.

You have focused our attention on the key questions.

You have challenged us to THINK.

I shall think long and hard before I reply.

Thanks for this interesting piece with not only Hitler’s history, but the political backstory that led to his rise. The point you make about Trump not being Hitler is valid given the nuanced differences you present. Let’s hope there’s room for nuanced, critical thinking out there. In our frustration with Trump, I think we search for some word, some analogy, to underscore how dangerous he is to our democracy, and lacking any, grab onto ‘Hitler’ as the extreme case. But you’re so right--we need to use our critical thinking skills, break from the hypnosis of herd mentality, and learn to talk to each other again. Why does that sound like utopia?