***PURCHASE THE COLLECTION ON AMAZON HERE OR CLICK COVER

~

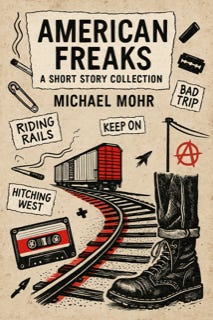

AMERICAN FREAKS

A Short Story Collection

~

Table of Contents

Introduction: 11

1. The Heart of the Emerald Green: 20

2. Tightrope: 33

3. Tommy’s Roof: 49

4. The New Toy: 70

5. Marilyn Monroe. Fat Girls. Death. Freedom: 78

6. American Freaks: 95

7. The Fish: 115

Bob Dylan as a Contemporary Female Writer in New York, 2019: 130

8. Stealing Cars: 148

9. Youth: A Short Story: 161

10. Riding the Night: 186

11. Secret Sex: 198

12. Yardo: 215

13. Splat: 226

14. The Caterpillar: 238

15. A Fatal Whiff of Youth: 252

16. Monster: 274

17. The Brawl: 292

18. Joanna: 301

19. Annihilation Time: 314

20. Torn Cords of Youth: 328

~

Books by Michael Mohr

~

The Crew (A YA literary punk novel)

Two Years in New York: Before, During and After COVID (a “fictional memoir” about living in East Harlem, NYC during the 2020 global pandemic)

Disgust and Desire (A COVID/NYC 2020 love story)

Controversial: The Substack Essays, Polemics 2022-2024 (an essay collection covering politics, literature and culture)

~

*Find links to all these books (read online and/or buy on Amazon) at: michaelmohr.substack.com

~

Praise for The Crew

“Some books mentioned by the characters in this novel include, Clockwork Orange, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, On the Road, Catcher in the Rye, and Crime and Punishment. Mohr’s novel deserves a place on the bookshelf near to these great classics.”

~Rebecca Jane, Book Reviewer and Influencer at Feathered Quill Book Reviews and U.S. Review of Books

#

“Tense and well plotted, THE CREW goes beyond its own story to teach us about ourselves. We feel for the characters because we can relate to them. This is not merely a punk book. It's much, much more.”

~Allison Landa, author of Bearded Lady: When You’re a Woman with a Beard, Your Secret is Written All Over Your Face

#

“This is a well-crafted and fast-paced story of a group of high school kids in the 90s. The protagonist, Dog, attends a fancy prep school but gets involved with a punk rock loving gang of misfits called The Crew. The reader is pulled into the narrative and action that is, at times, reminiscent of The Dead Poet's Society but with a lot more sex and punk rock action. Highly entertaining!”

~Matthew Long, writer at Beyond the Bookshelf

#

“I highly recommend this book for teens and parents alike.”

~H. Shamsi, Book Nerdection Book Reviews

Dedicated to my heroic, complex mother, who stood by me through all those years as best she could, despite my madness and cruelty. I love you, Mom. Without you I would not be either alive or the man/writer I am today. Thank you for never losing faith, even in the darkest of times.

~

Introduction

Truthfully, I should have published this story collection years ago. The stories in this collection represent a very different time in my life. The pieces are mostly dark, gritty, edgy, realistic, heavily autobiographical (but not entirely so), and mostly covering the period of my active alcoholism, the decade between 2000 to 2010 (age 17 to 27).

From my vantage point now—in 2025, at the much wiser age of 42—I look back on my former self with a mix of pride, confusion, humor, sadness, shock and forgiveness. In 2000 I was a sophomore at a college prep high school and had just discovered punk rock, booze, serious literature and girls. In 2010 I was in my later twenties, estranged from my family, living with a fellow drunk in a raggedy apartment in a rough part of North Oakland.

Much happened in those years.

I’ll never forget the first story I ever had published. (Tightrope.) It was 2012; I was 29 years old and less than two years sober. I was living in a tiny 500-square-foot illegal studio (a converted garage) with a little kitchen and bathroom and paying (amazingly) only $795/mo including all utilities. Back then writers still mostly submitted physical work and received physical rejections. (Or, I had heard, acceptances.)

One day I walked out of my apartment, barefoot, on a nice spring day, pushed open the old rickety wooden gate, and pumped over to the area with the half dozen silver flat mailboxes. I turned my key in the slot of my small box and found two envelopes. One was from an editor at the renowned literary magazine, The Sun. It was a rejection for a story I’d submitted, but for the first time it included a nice few-sentence-long personal note, signed by the editor saying that the piece wasn’t for them but that she saw my obvious talent. She encouraged me to keep writing. My heart soared. I remember that moment well. I had, at last, received some kind of support, a voice in the dark wilderness saying, Yes, keep going; you ARE a writer.

The other envelope was a congratulations and a contract for a different story, Tightrope—the more or less true but thinly fictionalized account of my drunken blackout and “kidnapping” in Mexico circa 2006, age 23—from a U.K. literary magazine called Alfie Dog Press. I couldn’t believe it. The contract included a check. It wasn’t much, but it was something. For the first time in my life I’d had a short story accepted by a magazine, and I’d even been paid. I stood there in the bright spring sunshine for a moment, contract in hand, and I almost cried. It was the best moment of my life up to that point. I was sober. And I was a published writer.

Things went from there. From that point on I had something like 20 or 25 stories published in little literary magazines and journals, as well as some articles and essays in various places. Ever since getting sober in 2010 I’d felt creative energy pouring out of me like sweat during a marathon run. It just flowed out of me. I could barely keep up. I finished the first draft of my YA punk novel, The Crew, mere months after getting sober. (And then spent 13 years revising and editing and going through rejections.) I felt like an unknown, non-genius but nevertheless highly inspired young Bob Dylan, the prose just raging through the fingers to the page like spiritual manna from heaven.

These stories, like I said, document a dark, often tormented time in my life. I was broken: Deeply wounded, very angry, totally lost, bitter, resentful and out of control. And yet, at the same time: In the end I was always a “good man,” if only unsure of who and what I was, tortured by childhood trauma, raised a lucky, privileged white rich kid in Southern California who nevertheless suffered much as a child.

My literary influences and forefathers should be easy to parse. Mostly Jack Kerouac (and the Beats in general) a la On the Road and Dharma Bums, both of which changed my life literally (I hit the actual road in 2006, thumbing around America), stylistically in terms of writing, psychologically in terms of how I thought about myself and the world, and the hurling out the existential window of bourgeois convention, which was the poison (I thought then) I’d been raised on. Beyond Kerouac were Denis Johnson (a la Jesus’ Son), Raymond Carver, and of course the obvious sources like Charles Bukowski, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Flannery O’Connor, Steinbeck, Didion, etc. (I later found Dostoevsky, Flaubert, Balzac, etc.)

I must have written hundreds of stories by now. The first one I ever wrote was physically on a little orange lined notepad I used to carry around with me when living in San Diego in my early twenties. I wrote how I felt, what I thought, what I witnessed (both internally and externally), about the pain of loneliness and metaphysical isolation, about the scourge of active alcoholism, about the women and the friends and the terrible ache for love which I craved and seemed to never truly find.

As I said before: Most of these stories are heavily autobiographical; some less so. With the exception of Yardo (completely made up), The Fish (a warm memory from my childhood), The New Toy (childhood), Secret Sex (about an old friend of mine), Bob Dylan as a Contemporary Female Writer in New York, 2019 (NYC age 36), Youth: A Short Story (before the year 2000) and Riding the Night (ditto), and Torn Cords of Youth (pre-teens), these stories are all mostly about “me” in the years I mentioned, the drinking days. Of course stories are never really, truly, completely about “you” even if you hold as close as you can to reality, because reality is always distorted based on the passing of time, the slipperiness of memory, wish fulfilment, ego and pride, our own narrative biases, self-mythologizing and self-heroizing, etc.

In this sense I cannot call these stories “memoir” or “nonfiction.” The moment I write about some vague notion of “me” and implant it onto the page it becomes in effect “fiction.” (There are many writers who reject even memoir as a category of nonfiction altogether.) And so the narrators of these tales—the protagonists or if you want the anti-heroes—are “made up” for all intents and purposes. They’re sordid semi-versions of myself which I do not claim represent “real life” fully. Some might contain slight exaggerations, distortions of the truth, false recollections, the merging of more than one memory or time in my life, less than accurate recall, etc. But they do represent, in total, a sense of the spirit of that time in my life. A psychological time capsule. In this way I hope the pieces resonate with something like at least a taste of universality.

Thus these pieces are fiction; short stories. I hope you enjoy them. A warning: These stories are NOT politically correct; they make zero effort to be safe, light or easy. The prose aims for subjective truth amidst the grit, meanness and roughness of a life unchained from social norms. If you can’t handle that: This collection might not be for you. I lived a very wild life in the years discussed herein. From being kidnapped in Mexico in a blackout to getting into a bad situation with the Hell’s Angels to firing guns while high on acid to stealing cars to fist fights to drunken wild sex with random women across America while on my own Kerouacian adventure called Life: These pieces represent a younger, crazier, more loose anarchic and restless version of who I am today.

I look back on that guy as a wild child.

I’m grateful that he survived to tell the tale.

~

American Freaks

A Short Story Collection

Copyright 2025 by Michael Mohr

~

The Heart of the Emerald Green

(Originally published in The New Guard)

~

There’s an iron cross up at the highest jump-off rock at the Punch Bowls. A girl died jumping off the rock in 1998. Her name was Angie Feckler. She went to Nordhoff High, the only public high school in Ojai.

The Punch Bowls is a big open pool of natural runoff water which coagulates at this spot off the main river. It’s not a river, really, but a big rushing shallow creek. Ojai is a small town 90 miles northeast of Los Angeles, nestled in the Topa Topa Mountains, where I was born and raised.

You access the punch bowls by driving west from the coast, near Ventura, about 15 miles on Highway 33, through downtown Ojai, then up the twisting, narrow Highway 150, along the cliffs, and then pulling into the parking lot of Saint Thomas Aquinas Catholic Church. From there, you walk along the road and then onto a wide trail which soon narrows and becomes a thin, craggy path running along the creek. You see mountains all around you. You smell the ripe scent of pine. You see chipmunks, sometimes deer. It’s possible to see mountain lions, but I never saw any.

The day which I will never forget started out normally. Me and my two best friends—Dane and Jared—parked in the church lot. It was a Sunday, late August, early evening. I had just graduated high school back in June. Dane and Jared were juniors. We attended St. Andrew’s, a private, Catholic, college-prep school. We were rich kids and we felt appropriate shame about it. I was driving my mom’s hand-me-down 1993 green Jeep Cherokee. It was 2002.

We got out of the car and I snatched my REI backpack. As we walked I heard the fifth of Jose Cuervo clink against the canteen of water. The canteen was made of thin, dented metal and had black thick wool around the bottom. It was my father’s; he’d passed it on to me. He’d told me it had once been his father’s and he’d used it in the mid-50s backpacking with my grandpa in Yosemite. That’d always been something he and his father had shared, and it was something me and my old man shared, too. I still recalled vividly the first time my father took me backpacking. I was eight or nine years old. My mom snapped a photo of me and him standing by the big oak tree out from of our house, me with my steel-frame pack rising above my shoulders, smiles on our faces.

*

Soon we were on the wide trail, moving fast. We had perhaps 45 minutes, maybe an hour of light. Lazy sunlight glinted off the creek. The water rushed and gurgled along slick rocks. Jared—tall, pale, with his beady black eyes—picked up a few small stones and hurled them at the water. Dane, short like me, bedraggled hair, wearing his torn Megadeth T-shirt, walked behind me. He was slower, more contemplative. In the woods, while hiking, he liked to be silent and think. Jared, a ways ahead and to my right, lugged a Marlboro out. He placed it between his thin lips, lit it with his scratched blue bic, inhaled, and blew a web of nasty smoke out.

I thought about how empty the parking lot had been. I thought about how in three weeks I’d be taking community college classes in Ventura. Not exactly what my parents had expected and hoped for when they’d sent me to such a prestigious college-prep school. I should have tried harder, studied more, cared, given a shit. But the truth was I didn’t want to go to college. I wanted to gain life experience. I wanted to get laid. I wanted to drink. I wanted to fight. I wanted to get a PhD in the school of hard-knocks.

*

Then suddenly we were there. The creek rushed harder, and it opened up and we were in a little gulch, a mini valley, and there were cliffs a little ways above us, and we veered sharply to the left, up some bone-white and beige gargantuan boulders and we stood up at the top of the rise and there, down below, was the Punch Bowls. It should have been called The Punch Bowl, cause there was only one bowl of water. It was green; emerald green. Deep, probably twenty, twenty-five feet. I saw a silvery fish, big, swim furiously in the middle. I pointed at it.

“Little bastard,” Jared said, squinting from the low rays of the sun. He inhaled more tobacco; the orange at the end of his Marlboro glowed.

Dane stood between us. He and I had been friends since last year. I met Jared through him. He and Jared had met freshman year. Dane lived a mile from me in town and drove his father’s 1980s Mercedes Benz. It sounds cool but the thing had problems constantly. It was always in the shop. It reeked of old cracked leather. When it ran Dane would pick me up late on a weeknight, after my folks went to bed, and we’d drive aimlessly around Ojai until 2am, laughing, smoking cigarettes, trying to score beer, listening to Megadeth. We always had the windows down. Sometimes Dane would say, Are girls ever going to pay attention to me?

We sat down on the wide, smooth boulder. No one was around. In June and July it could be crammed with high school kids from all over town. Gorgeous girls sunbathing in bikinis; muscle-y dudes showing off their arms and jumping from the first or second jump-off rocks. No one jumped off the highest one. Where the iron cross was. Where Angie had jumped from and died. Not since ’98. That must be 70, 80 feet up. I’d jumped from the second highest. That one was maybe 50 feet. The problem, too, with the highest spot was that it had this jagged outcropping at the lip. I’d gone up there once, just to stand on the edge and glance down. I nearly got vertigo. The emerald green pool looked so miniscule from up there it seemed like a joke. Like you couldn’t possibly make it.

I unzipped the backpack. I pulled the canteen out and the fifth. Sunlight lanced off the Jose Cuervo. Jared took the fifth. I twisted off the cap from the canteen and slugged water. I passed it to Dane.

Jared drank from the fifth. He sniffled and shook his head. No chasers.

“Lemme grab a smoke,” I said.

Jared pulled his red-and-white pack out and handed it over. I snagged one and inserted it between my lips. I used Jared’s blue bic and lit up. I inhaled the cloying tobacco deep into my lungs. A breeze rushed through, and the wind through the trees made it sound like traffic in the distance on some raw, rugged highway.

I handed the pack to Dane. Jared handed me the fifth. I twisted the cap off. I drank a deep one. “Ugh,” I said. “Nasty.”

“What do you expect?” Jared said.

Dane took the fifth from me. My fingers bounced he snatched it so fast from my hand. He drank. I thought again about that empty parking lot, the newly paved black asphalt. Summer was almost over. I was done with high school. It was over, those four years of excruciating hell. I would go to community college, study writing, move out of my parents’ house in a year or less. I’d be free. The idea both enthralled and terrified me. I imagined some oasis, living in some tiny, cramped studio, writing the Great American Novel, something like Denis Johnson or Kerouac or Bukowski. But some little voice internally knew it’d be different.

Jared took another hard swallow. I did, too. Then Dane. Already I felt buzzed. The shadows had increased around us. The sun was nearly down. We needed to swim before darkness took over.

The fifth was half killed. Jared rose, his long pale arms used as aids, and he stripped his torn jeans off. He wore his white boxer briefs. He stepped carefully down the boulder and leapt off, screaming, saying, “Holy Fuck!” and dove into that perfect emerald calm. I watched his body propel into the green, and then do a sort of curving arc, and emerge twenty feet away on the other side of the pool. Dane jumped up. He tore his Megadeth shirt off, waggling out of it, and then jogged down the boulder and did an awkward cannonball. I closed my eyes. I smiled. I watched them. Dane yelled loudly as he swam around.

“Fuck it’s cold,” he said, thrashing hard to get warm.

“It’s not that bad,” Jared said, his long pale arms doing a lazy breaststroke.

I untwisted the cap of the Jose and drank. God, this was good. This, right here and now. I wished I could freeze time, freeze this moment. Me and Dane and Jared. Together. Before it all changed. I knew they’d stick together. They’d met first, had bonded longer, and were still in high school. I’d be on my own. Alone again. But I was used to that. I hated working at the restaurant. But it was money. And I had the Jeep. Soon I’d get the hell out of this dead-end town.

Here, in the little valley, at the punch bowls, it was simple: Boulders and trees and mountains. It felt like when I wrote sometimes, when I got into the zone and it was like time just passed. Hours would go by like nothing. But then there was real life, and that was different; that was hard. That’s what I was afraid of. High school, though chaotic, had provided a routine, a safety net of sorts. But now? That safety net was gone. I was a penny dropped into a well with no bottom. Where would I land?

I suddenly had this feeling like this might be the last time I’d ever come here. At least with them. At least before I became a man, a real grownup. There were maybe two or three swallows left. I drank, deep. It was almost gone. I swigged down the last remnants.

I stood up, wobbly for a second, but then I gained my balance. Dane and Jared were relaxed, swimming like seasoned fools.

“C’mon in,” Jared said.

I walked to the right, down around the other side of the massive boulder. I pushed through some Douglas Fir branches and was on the red-tinted trail. There were pine cones all around, broken twigs, fallen leaves. I felt my heart banging in my chest, my legs rubbery.

When I got to the spot where the first lookout was, I tromped out to the ledge. I glanced down from twenty feet up.

“Hey, assholes!” I yelled down.

They looked up. Jared, with his shiny black hair and black little eyes. Like a rat. And Dane, his longish brown hair all slick and flat against his skull.

“Jump,” Jared said. He seemed serious.

I laughed. I walked back to the trail. I hiked again. It took a few minutes but I reached the second jump-off rock. I stepped to this ledge.

I looked down. They were already looking up, hip to my game. From here, when I looked out above the little valley, I could see the trees, and some mountains, and the distant hills and more of the winding creek. It made me think of St. Andrew’s, and of Ojai, and of Highway 33 and of backpacking in the canyon with my father as a child. Once, my father and I had been close. He’d been like my hero. But all that had changed. When I started drinking and rebelling sophomore year, everything between he and I had melted away. All I’d seen was a bored, upper-middleclass tycoon. All he’d seen, I’m sure, was a spoiled little shithead. We were even.

“You gonna jump man?” Dane yelled. His voice echoed against the boulders.

I walked back to the path. Why I felt the need—the compulsion—to do this I didn’t know. But it felt important somehow. Like some ritual. I had to do this. It was only as I walked further, and reached the ledge, that I understood I was crazy and slightly drunk.

*

I saw the cross. It was old and bent slightly; ancient, dented metal. Maybe two feet high, three or four inches wide, an inch thick. In gray text it said, “Angie Feckler. Nordhoff. Class of 2000.” I swallowed.

I stepped to the ledge. I kept my body as far back as I could but I moved my face forward to look out. The valley was wide open. I saw more mountains, more trees. Even what appeared to be the tiniest edge of a twisting highway. Must have been 150. Wind ran through the trees again, that all-encompassing rush of traffic sound. Nature, making her declarations.

Dane and Jared started yelling. I couldn’t hear everything they said from all the way up here but I caught some key words: “Idiot,” “asshole,” “get down here,” “don’t jump.”

It was so, so far down. I mean impossibly far down. The emerald water was tiny. It was like trying to jump from a 100-foot cliff into something the size of a Jacuzzi. I couldn’t believe it. And the lip. The lip stuck out too far. There was a second lip, ten, fifteen feet below, and it stuck out even farther, like a middle toe longer than your big toe, and if you hit that you better believe it’s all over. Maybe that was how Angie had died. Or maybe she’d hit the water with such impact that she drowned.

Jared cupped his palms round his mouth and yelled something. Dane swam across the water and pulled himself up and out of the pool. He stood on the boulder and I knew he was going to come try to get me.

I stepped as close to the edge of the ledge as I could. I remembered going to Lake Nacimiento with my friend Greg when I was a kid. We’d jump off cliffs half this height. I sometimes had that debilitating fear, that fear that prevented you from jumping. The key was to push through it, trust yourself, and just commit. You stepped back, you moved forward, you leapt. It was an act of faith every single time.

I looked back down. Jared was off to the side, sitting on the edge of the boulder. Dane was gone. He was probably halfway up here by now.

I glanced back down one last time. My breathing was fast and shallow. I did three or four quick, fast breaths to pump myself up. I jumped up and down.

“Alright, man,” I said to myself out loud. “Do it.”

I took three steps back. Big steps. I waited. I heard Dane’s voice a ways down the trail off to the side. If I died they’d have two crosses up here. Would I be missed?

Right as I heard Dane’s voice very close, and heard some bushes being moved by his hand, I took a few big steps forward, felt that terrible fear, wanted desperately to stop myself, stepped onto the ledge, and shoved myself off.

*

You know that cliché in films where a character jumps off a bridge to their death and on the way down their whole life flashes before their eyes? Well, that didn’t happen exactly, but something not totally different did. I remembered a moment with my father. I was 16. I’d been drinking for maybe six months at that point. By then my father and I had become strangers. I’d been stealing crisp twenties from his black leather wallet for quite some time and with those twenties collected I’d gotten my first tattoo at a parlor on Main Street in Ventura, a place owned and operated by Hells Angels.

My father stormed into my room that night. I was lying on my bed. It was a Wednesday in October. He stood in the doorframe, his bald head, his prescription glasses, wearing a tucked-in baby-blue collared shirt like always. His beige Dockers had that crease down the front, crisp and perfect, like the twenties I stole. His pale blue eyes gaped at me and I remember having that feeling like, You’re not my dad. I’m not your son. There’s been a mix-up.

“Son,” he said, adjusting his glasses. Then he took the glasses off entirely and cleaned them with his collared shirt. Grooves remained in his skin from the glasses. He put them back on. “Did you steal from me to get your tattoo?”

I stared at him for what felt like a very long time. He’d been the most conflict-avoidant man I’d ever known. I felt like crying, so I said, “Get the fuck out of my room.”

“Don’t you talk to me like that,” he said.

I swung my legs off the edge of the bed, rose, and approached him. We stood inches away. I thought of the camping trips; I thought of the time he bought a board and wetsuit just to go surfing with me when I was 12. Those days were long gone.

“I said, get the fuck out of my room,” I repeated.

We ogled each other. I thought he might actually hit me. Or maybe I’d shove him. But neither of us said or did a thing. We just stared at each other. Time passed. And then he looked down, at my fresh ink, back up at me, and in his eyes I saw the most righteous pain. It made me want to hold him. It made me want to be six years old again, being read Dr. Seuss by him while I laid in bed, feeling safe and warm.

My father said nothing. He turned around and walked away. Once he was gone, I closed the door and locked it. That was when I made the decision. That was when I promised myself I’d never let emotion get the best of me. I would protect myself. World be damned.

*

I was off the ledge, in the air. I saw the extended lip, the second one, and, thankfully, I passed it safely. Then it was just this non-stop air drop. My heart fell in my chest; it was like being in a free-fall elevator.

And then, suddenly, boom! I crashed into the water. I plummeted down, deep, hard, into the heart of the emerald green. Almost to the bottom. Then I slowed, my momentum was softened, and I swam easily back up.

I broke through the surface.

“You crazy fuck!” Jared yelled. “Jesus Christ, man! I can’t believe you did it!”

I shrugged, swimming nonchalantly for a moment. I saw Dane poke his head out from the second jump-off rock.

“Dude, are you alright?” He yelled down.

“Just fine,” I yelled back.

I swam over to the boulder and climbed up, losing my balance on the slippery surface several times before finally succeeding. I lay on the cool hard surface. It felt like hugging God. All of the world seemed to be hugging me back.

Tightrope

(Originally published in Alfie Dog Press)

~

Going to Mexico was a bad idea, and deep down both of us knew it. But the great thing about my roommate was that every time I came up with a bad idea, I could count on him to be on board. My brain was always concocting thrilling plans in which the only person I could include was Hilly. No one else would be crazy enough to walk that tightrope with me. They’d be too jaded to see the adventure of it, or too nervous to take the risk. No, when these prolific ideas came to me in the night, it was dear old Hilly whose face I saw.

And that's how it came to be that I woke up in the early morning San Diego fog proclaiming, “Hey, Hilly…ok man…I got this great dig, ya see. You and I…”

“Yeeeeessss…” he interrupted, drawing out the “e.”

“Listen Hill, listen. You and I…we’re gonna go to good ole, MEX-I-CO, Baaaby!!!” Hilly sat perplexed, his eyes registering somewhere between indifference and exuberance — as if the plan was a no-brainer. Of course we’d go to Mexico; we lived in San Diego, thirty minutes from the border. Living at the gateway to a foreign land, a land where anything might happen, well, it was gonna happen at some point, right? It was just a matter of one of us deciding it was time. We both knew it would be me.

After finishing breakfast, we headed out for the bus that would take us to good ‘ole Mexico. We found the seats farthest in the rear, as we had done during our high school careers, and probably would continue to do for the rest of our lives.

Hilly looked good. I looked good. The world looked good. Mexico, the idea of both of us in it for the next twenty-four hours, made life seem exciting, the way you felt as a kid getting in the car with your parents as you left for a road trip. Yet as the bus careened through downtown San Diego I felt some warning, some bell sounding in the depth of my soul. I couldn’t be sure what that bell meant, nor what, if anything, going to Mexico meant. But I did have the sensation of fear.

Nearing the border, we were in such a state of excitement that I thought we would go crazy and jump out of the vehicle while it was moving. The train dropped us off in downtown Tijuana and turned around, heading back to the Land of the Free, Home of the Brave. There was no turning back now.

We started sprinting — toward what we weren’t sure, maybe the freeway leading away from Tijuana toward fun and freedom.

We stopped, bent over, breathing. Still hunched, Hilly put his hand on my shoulder, pressing.

“Gonna be a search n’ destroy mission, eh ol’ boy,” Hilly said.

Looking for a cab, we were flailing our arms in the air. In no time a taxi with advertisements in Spanish pulled over. I jumped in the back and Hilly followed, slamming the door. We knew we were on the brink of being spit into the dragon’s lair. Who knew what would be waiting for us.

The road wound up, up, up, like a concrete snake slithering toward sand. Tijuana was behind us, and Hilly seemed to relax. I know I did. Hilly’s arm hung out the door, flapping against the taxi as the force of the wind blew it back.

Coastal villages passed — shanties with cardboard walls, covered in blankets. Half naked kids played. Dogs, ribs sticking-out, wandered noses to the ground, through lots littered with brokendown vehicles, old washing machines, trash.

We were approaching Rosarito; the all-night party was coming.

The taxi stopped in front of a bar, as we’d instructed. Hilly paid the driver.

“Pay me back with drinks,” Hilly said, shoving us out of the cab. The driver waved, flipping a

U-turn, heading back to the border to pick up the next batch of American kids.

The place was bigger than it looked from outside. Men sat idly. One man was shooting a game of pool, twisting the cue stick into the blue chalk cube as he stared. Hilly pulled up a stool at the bar.

Beers and shots went down. Hilly confided he’d brought his switchblade. To prove it, he opened his jacket, quickly brandishing the metallic blade.

We moved to another place. The new bar was smaller. Hilly seemed thrilled, bouncing like a

Mexican Marlon Brando, with a too-big head and too-dark everything. He swaggered like Brando as he tapped over to the bar stool. Drink was fueling him. He eyed the place for a good fight, or a woman he could harass.

I ordered beers and shots of tequila, which we downed in minutes. We were trying to catch up to Mexico. It seemed as if Mexico was always one step ahead.

We walked down the street to The Gold Nugget, the name written in English, neon bulbs flashing, the Mexican tribute to Las Vegas.

In the center of the club was a stage in the shape of a figure eight — two oval platforms, seats along the edge. A naked girl, sixteen at best, danced.

I began to feel my body slowing. I watched the girl — breasts, ass, feet moving in dance steps. Her set ended and Hilly hit the john. The second he walked away, I knew.

My friends, most of whom were really just drinking buddies, knew. Once I got close to blacking-out, I would slip away. The next day they would ask me, where’d you go last night? I would answer: I don’t know.

Beer in hand, I walked out of the strip club. From the street I could still hear jazz music. It was dark. Houses began giving way to closed shops and markets.

I jolted at the sound of tires on cobblestone: The police. Mexican police — corrupt cops. Two officers got out. Pulling my arms behind my back, one of them ran his hands up and down me. The one searching shoved his hands in my pockets and found my passport and wallet.

There was no cash in the wallet, which he flung.

He tossed the passport alongside my wallet. The officer said something in Spanish. He repeated it; I shook my head, indicating that I didn’t understand.

This seemed to frustrate him. He pulled out cuffs, throwing them over my wrists. Immediately the two officers started fighting, the pitch of their voices getting higher. Mexican jail — what would that be like? How would Hilly find me? The cop shook my shackled wrists. The two men had a stare down.

Then he unlocked the cuffs. Without a word, they took off, dirt flying. I had escaped

Mexican jail. Hilly would be proud.

I drifted over to an area where light was blocked by an alley. Leaning against the wall, I was grateful for a rest. My passport and wallet! I reached into my pocket, realizing I’d left them back in the dirt. Panic settled. I started to organize a plan, but it was too late.

My breathing slowed. Eyes closed as I let my body slide, sinking deep, deep, deeper into oblivion.

“Argggghhhh!!!” I bolted, sweat down my cheeks. I was in a moving car. I wasn’t dead. It was dawn. The sun had come up over the hills, beginning its ascent.

I counted four others — one driving, one riding shotgun, two guys next to me in the back. Who were they? Where were we going? The car felt huge, like a Buick. No one looked at me, not a sound — no talk, no radio, nothing.

“Um…excuse me, but…ahhh…where are we going, and uhh…”

I was cut short by the driver. He turned around and spoke in Spanish to the guy next to me. The guy started answering. They conversed, neither of them talking to, or looking at me. Was I being kidnapped? Kidnapped in Mexico? What if they were going to keep me in some dungeon, away from civilization? Or kill me and sell my organs? Or worse…hold me hostage for the rest of my life — beaten, underfed, tortured, far, far away from the American tourist traps. Hilly would look for me. My family would look for me. But they would fail.

The girl riding in front turned, facing me. She appeared Mexican, but was lighter-skinned than the others. Her hair was pulled in a ponytail, an appendage, as if the hair had power, as if it represented her personality.

“You pass-out, eh. We grab you, no get grabbed by la policia.”

She faced forward and slumped. Then she turned again, wrapping her arm over the seat.

“La policia en Mexico, they no mess around, eh.”

“Where are we?”

The girl glanced at the driver, said something in Spanish.

“Four hours south of Rosarito, mi amigo de Americano.”

“Where are we going?”

She eyed the driver again.

“We make a connection,” she said.

“A connection?”

Her eyes told me to keep my mouth shut.

“Could we turn around, go back to Rosarito? I need to go back…”

The girl laughed, her mouth revealing stained teeth, all crooked.

“No mi amigo; not likely.”

Her hand flipped over the seat with a beer in it. I took the Tecate. In minutes, the arm returned with another.

I wondered where Hilly was, and what had gone through his mind. I was on an adventure.

The silence didn’t seem so hostile anymore. I assumed the others didn’t speak English. That was alright, I had a translator. I tapped the girl’s shoulder. “Si?”

“What’s your name?” I asked.

She smiled.

“Isabel.”

I was glad to be conversing, almost like we had just met in a bar.

“Beer?”

She handed me another Tecate.

“Gracias.”

The car stopped. We were parked across the street from what looked like a motel, the kind of place where you bought and sold drugs, hired prostitutes. The driver spoke to the two men. The three of them got out, walking toward the motel. Isabel and I remained silent.

“Isabel, what are they doing?”

She looked out the window toward the motel.

“Jesus buy guns from connection. We come twice a month, drive here to make pick-up.”

“So they’re buying illegal guns…and running them back to T.J.?”

Isabel’s eyes relaxed.

“Yes, buy guns… sell in Tijuana.”

“Isabel? Am I going to make it back to Rosarito?”

She looked at me with pity. She was beautiful if you didn’t see those teeth.

Jesus and the two men returned, one of them carrying a load hidden under blankets. The man opened the trunk. Jesus played with the ignition, as we waited for sounds of life.

“Amigo, amigo…wake up, eh?”

I woke to Isabel shaking me. The car was stopped on the side of the highway. Jesus was smoking a cigarette behind the wheel. The other two men sat looking straight ahead, saying nothing. Isabel looked anxious.

“You must go now, amigo… we here in Rosarito.”

“Gracias, gracias, muchas gracias, mis amigos!!” I said.

The second my feet hit dirt Jesus pumped gas; the clunker lurched, its door slamming from the motion. Isabel waved out the window, her arm swaying back and forth in the distance. Walking inside El Mercado de Rosarito, I tramped down an aisle, grabbing a carrot from the vegetable bin.

I sat on a bench that looked like it had been there for decades. I munched on the carrot and tried to think. People eyed me. I was the minority now. Where were all the tourists? A Mexican girl my age walked out of the market and sat down on the bench.

“What’s the deal with you?” she asked, catching me off guard with her perfect English. “It’s a long story.” I paused, looking down at my feet. “I need to get back to the States…don’t have any money or anything, not even a passport.”

She cocked her head. Her eyes were trying to challenge what I said, prove me a fibber, a story-teller pulling a joke.

“You really have no money? No passport?”

“Really.”

Her name was Luisa.

“I will buy you food, and you will hide in the back seat of my car.”

Luisa returned a few minutes later with small tacos — beef and chicken, lettuce, jalapeños, and guacamole. I realized I hadn’t eaten since yesterday morning — the breakfast Hilly made — and I was starving. We destroyed the tacos. Afterward, we sat sober in the challenge we were about to undertake.

The sun was high as we drove north toward the border. Baja: land of adventure since the beginning of time. The car rocked and creaked as we wound up, up, along the cliffs, reaching a plateau before shooting down into the valley.

Over a ridge I could see the freeway overpasses, tangled and crowded, cars speeding. We were getting close. I could feel the border calling.

“Get in the back, grab those blankets and pull them over you. Get as low as you can,” Luisa said.

I glanced one last time at the hills in the distance, at ‘ole Mexico. I climbed in back, lowering myself to the floor, and grabbed the blankets, pulling them over me. I left my eyes uncovered.

We took a big, looping turn.

Slowing down, we inched forward.

“Ok,” she said, “silence.”

I took one last breath and buried myself. Time stopped as we crawled. Then I heard Luisa roll her window down. A gruff male voice spoke.

“Hey there, where ya coming from today?”

“Ensenada,” Luisa said.

“Carrying anything with you today? Weapons? Fireworks? Drugs? Anything like that, ma’am?”

“No,” Luisa said.

“What’s in the back there?”

Terror cut through me. I couldn’t breathe. I was sure he would hear my heart pounding, or I would gasp for air and blow it.

“Just some picture frames I picked up in Rosarito,” Luisa said.

“Uhh huh…” the man said.

“You know, you’re quite cute for a border patrolman…I mean…that’s what they call you,

isn’t it?”

“Sure, that’s right…border patrolman. Course, I used ta be a Marine, back in the day… you shoulda seen me then, you’d really have gone for me…hahahaha!”

Silence.

“Alright…you’re fine ma’am…go ahead, move on.”

Luisa rolled her window up and pulled forward, picking up speed, leaving the border behind us. I yanked the blanket off, gasping for air.

For the first time since the previous day I felt safe. Back in the U.S of A! We laughed and

Luisa put her hand on my shoulder, both of us savoring the victory, the great escape.

*

Downtown San Diego traffic was crazy. Luisa pulled over. The car idled as she reached into her purse and pulled out a five dollar bill. She pressed a peso into my palm, “for good luck.” She drove away, melding into traffic.

I arrived at our apartment. The shower was running. I stood listening, thinking about everything that had happened. Then I burst into shouts.

“Hilly, Hilly, hey man, it’s me, it’s me, Hilly, Hilly!!”

The shower stopped; Hilly shoved the sliding-glass open.

“Holy God in Heaven man, I can’t believe it’s you!!! I thought you were dead for sure man…holy crap, you disappeared…I looked all night for you, everywhere! In the morning I checked…like…three jails! I even took a taxi to Tijuana and checked the jail there…” Hilly wrapped a towel around his waist, bantering, telling me the tale from his side, repeating over and over how glad he was that I was alive. He’d been certain of my death. I told him the story, his eyes rising and lowering with each nuanced point. He shook his head dramatically.

“Jesus man…you know how lucky you are, you stupid bastard?”

I laughed and told him I did. He grabbed my shoulders and hugged me, which he had never done before. The apartment looked new, like I was seeing it for the very first time. Sunlight slipped through the windows, the light and shadows falling in contrasting streaks across Hilly’s body. He seemed like a new man, almost special.

He told me a girl was driving down from San Francisco; they were going to a party. He asked if I wanted to go. I told him I did. He added that he had scored psychedelic mushrooms.

“Can I have some?” I asked.

Hilly looked perplexed. He sniffled and shook his head at me. “You crazy bastard.”

He grabbed his leather jacket, extracting a zip-lock baggy. I fingered the heads and stems, the gold part of the plant, the potent stuff. Selecting one I tossed it in my mouth and chomped it down, just like I had the carrot a few short hours ago. Hilly watched, mouth open.

“That’s some heavy shit you just ate man…yer gonna feel that in about forty minutes.”

I just grinned. “Well, Hilly…think I’m gonna take a shower, then pass out for a while before we go out.”

Hilly looked at me with the frustration of a mad man trying to save someone he knew he couldn’t.

“Take a nap? Dude…you just swallowed like an eighth bud, you ain’t sleepin’ anytime soon.”

He was right, of course.

I stripped out of the clothes I’d been in for twenty-four hours and got in the shower. I had about thirty minutes until my brain would be overwhelmed. Standing in that vacuum, that space harboring trouble where Hilly and I so often met, I thought about the ordeal I had been through. I knew in that moment that I was young and reckless. There was pride in that image, but it scared me, too. How was I going make it past twenty-five? Somehow, in that second, I understood that living in a no man’s land between dreams and reality was a dicey gig. But I didn’t die. I was alive, standing under the surging hot water. I had youth. I had time. I had chaos. That was all I needed.

I got out of the shower and grabbed a towel, wrapping it around me.

Only twenty minutes left until annihilation.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Michael Mohr's Sincere American Writing to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.