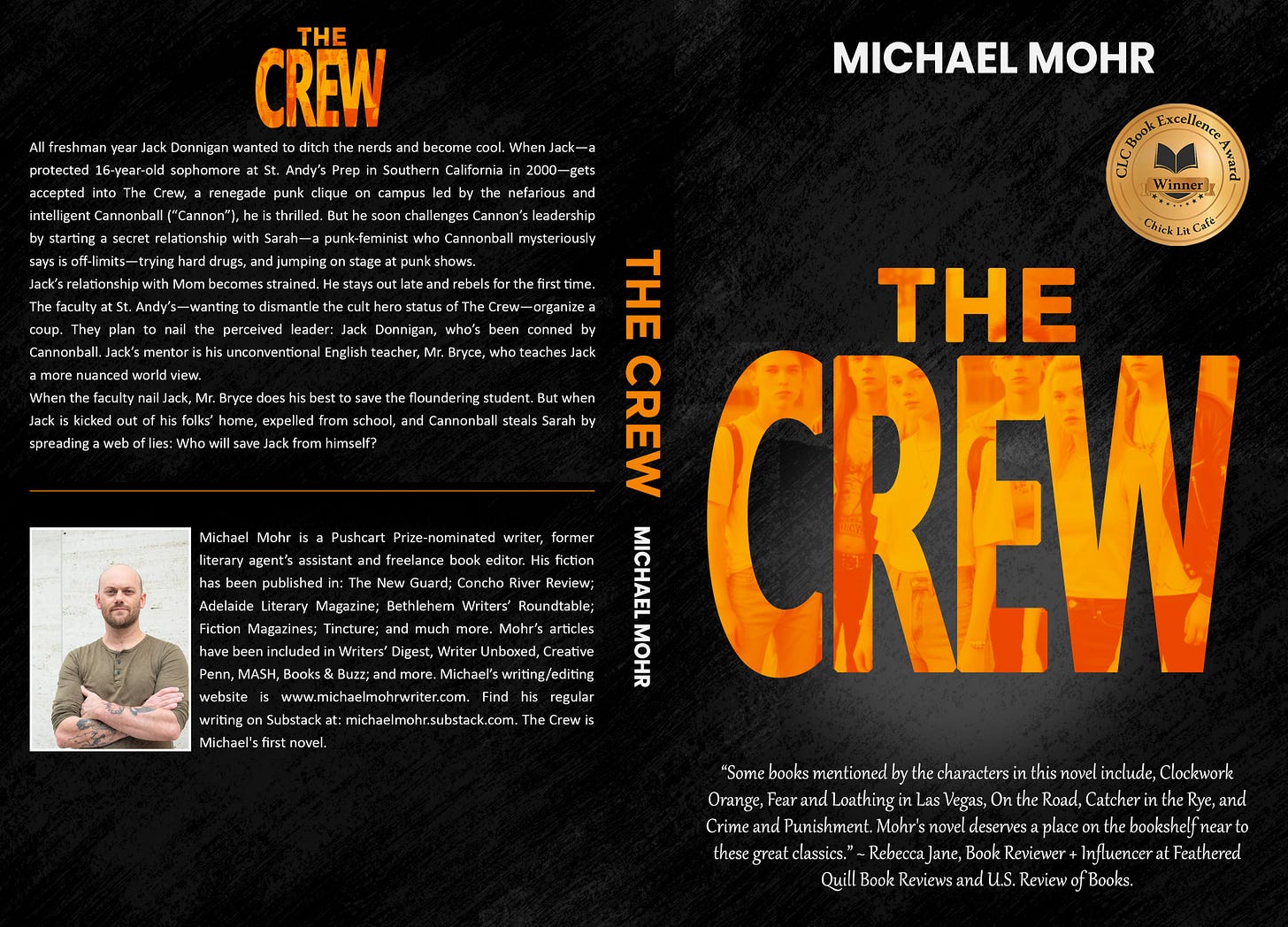

^^^^^Here is the final cover for my punk-literary YA novel, The Crew. Thanks go out to

for the basic cover design. Check out his stack HERE. Click on the cover OR HERE to purchase the book ($99 cents for eBook, $13.99 paperback, $16.99 hardcover).^^^^^~

I’ve never been into sports. It’s just never been my thing. I’ve always been, I suppose, a mix of too selfish, too ego-driven, and too individualistic for team-sports. As a kid and teen—as many of you know—I was first an avid, sponsored, competitive surfer (never very good at competitions but a solid natural surfer), then a skateboarder (in the 1970s style of “surfing concrete”) and then a punk rocker. All three at various points were deeply enmeshed.

My friends and I surfed and skated together—oh, and don’t forget my obsession for a while with BMX—but at the end of the day these were solitary, individualistic pursuits. You relied on yourself, not teammates. It’s true that I was a decent runner—I competitively ran the mile in track as a boy—but again, that was a solo endeavor, you versus the track. You didn’t rely on others in the same way that team sports do.

I even once played Little League baseball. I was young; it was the early 1990s. I played in Ojai, the little mountain town north of LA where I grew up. I was terrible, being shunted to Left Field (or “Left Outfield” as I called it until recently). I played for maybe a year.

My friends and I in high school were into loud, brash punk shows, drinking a lot of alcohol, driving scarily fast, chasing girls, running from the cops, surfing and skateboarding. We mocked the jocks and hated the sports kids. What was the point of sports, I often recall wondering. Even later, as an adult, understanding that sports were a symbol for war, and a relatively healthy way of exploring our inner grotesque drives, I still didn’t fully comprehend the purpose of watching a bunch of people run back and forth on a court hurling an orange ball into a net, or ramming into each other with brute force, or trying to smash a small white ball with red thread into a field. It lacked a basic inner logic for me.

Even now, at 41, when I meet men I don’t know and they say something like, Man, how bout that homerun against Kansas City on Friday?, I freeze up, feel insecure, and do one of three things: 1. Nod my head as if I know all about it and say, “Yeah.” 2. Pretend I really know my stuff and say, “Wow, right? Incredible hit!” 3. Admit the truth and say, sheepishly, “Oh. Sorry man. I don’t know sports at all.” If I choose the latter—less likely—I’m often gaped at as if I were some green alien from Pluto which happens to be wearing a human meatsuit. The kinder guys try to hide their confusion and disgust, but it always reveals itself one way or another.

To put it bluntly: I’ve always been my own man. I’ve never been a team-player, a follower, a conformist, someone who craves awards or good marks for running around in a uniform. I prized reading, writing, intelligence and adventure above anything else.

This all changed, however, when I fell in love with my wife, Britney, and met her son, Brayden. At the time he was 16, in summer 2022, when Britney and I started dating. Now he’s 18 and about to graduate high school. He’s at that painful, pivotal moment in life where he’s no longer a kid, but not quite a full-fledged “adult” yet, either. In the past two years he’s gone through a profound amount of change: He got a steady girlfriend for a while (they broke up later), got his driver’s license, inherited his father’s truck, started working his first job, and began to become slowly more and more independent from his mother. (This has not been easy for Britney.)

Brayden loves—and I mean loves—baseball. He’s like I once was with surfing. My friends and I used to surf almost every day, and we’d go out there for hours and hours and hours at a time, getting out only to eat and briefly rest. We were obsessed. At age 12, 13, 14, surfing was like sex to us; better, even. You could do it all day. It never grew boring and it never let you down, even if the waves weren’t good. And if the waves were terrible we’d skate my buddy Ryan’s empty pool, pretending we were surfing. Next best thing.

Since I got sober in 2010, the new obsession for me—and the true depth of my lifelong passion—has been writing. That is a fire which I’m certain will never fully burn out. For Brayden, it’s baseball. The kid eats, sleeps and drinks the sport. At first I was resistant to going to his games, played at his high school field, Cabrillo, in Lompoc (where we live, 50 minutes north of Santa Barbara). But, slowly, over time, I began going to the games. And I began enjoying them.

The games aren’t “just games” with Britney’s family. Her mother, aunt and stepdad always go, and we sit as a group by the fence on the left side of the field. There’s a small set of wooden bleachers and a gaggle of older locals gather there behind us and shout for Cabrillo. Sometimes, we traveled to other fields to play other teams, usually not farther than an hour. (Britney went to a few multiple hours away.)

Over time I began to appreciate the game, enjoy it. I started, for the first time, to understand the “inner logic” inherent in baseball. The game clearly required a lot of skill. There were so many endless shades of direction players could go. The pitcher could throw any number of styles. He could also throw to any one of the bases, trying to get a stealer out. A runner could slide or jump. A batter could swing hard or wait for balls and try to get walked or could bunt and hope to make it to first. There was a light, tense anxiety always hovering around us at the games, hope mixed with dread mixed with excitement.

I got to know the different players, who the best hitters were, who the fastest runners were (Brayden was fast), who bunted, who hit line-drives and homeruns (Blake), who the strongest pitcher was (Gage). It was fascinating watching the coaches interacting with the players using signals and baseball sign language; they’d created their own syntax and grammar and intrinsic non-verbal understandings.

In short, I became invested in the games. Britney—a good mother—tried to make as many games as possible, often working on Saturdays so she could get one weekday off to go, and also taking off an hour or two early from work to make other games. She participated, and wanted her son to know how much she cared. (His father was very involved as well.)

Oftentimes Brayden seemed annoyed when Britney tried to talk to him at games. I understood this strongly, grinning internally. How many times had I told my mom to not talk to me when I was at school or hanging out with my punk buddies? The last thing an 18-year-old male wants is his mom around. (This doesn’t indicate any lack of genuine love or affection, it is simply the nature of psychological transformation which occurs at this time in life.)

Brayden was a fast runner, a good outfielder (he played center and right field), and was strong in the bunting and being walked department. He had a solid eye for balls, versus strikes. Sometimes he swung, and often he hit an easily caught ball and/or struck out. But he was indispensable to the team. Like most young men, no one was harder on Brayden than himself. I saw that in his facial expressions when he struck out or his hit was caught.

We got to know some of the other players’ parents and even attended a couple little local parties for the team. It was fun. Much drinking was involved. Everyone was friendly. I felt totally out of my element, sure, but at the same time I was grateful for being automatically accepted, no questions asked. My ex’s parents had rejected me out of hand because I had three knocks against me in their book: 1. I wasn’t Jewish; 2. I had tattoos; 3. I’d once been an active alcoholic.

So, in many ways, when it came to Britney’s family, I felt redeemed spiritually in some metaphysical manner.

Sitting together by the left field fence, Britney’s mom, aunt and stepdad and I also used the time to whisper, chat and bond. We told jokes, asked each other what had just happened (“Did you see that line-drive?”; “how’d he get out so fast?”; “That was a BALL???”) We unfurled our life histories and stories to each other. It was a fun, laidback, communal family experience which I began to cherish.

I started going to games more often. I understood Brayden’s strengths and weaknesses, and same for the other players on the team. Half a dozen of them—Brayden included—were seniors which meant this would be their final season together. Most were going to Allan Hancock, the local community college. Gage had already been accepted to pitch there. Brayden was uncertain whether he’d make the team or not; evidently Allan Hancock had a very good team. So, as the months went by, and Cabrillo absolutely dominated the games (they had a record at the end of something like 24 wins to 3 losses), and it became more and more likely that they’d go to the CIF post-season tournament—CIF: California Interscholastic Federation—I became more and more emotionally connected to Brayden, the team, and their ranking.

*

As Britney and I have been preparing to move to Spain in the fall—working on selling my house and renting hers out, filling out paperwork for our visa, etc—we’ve also been, these past months, wondering what would happen with baseball: Would Cabrillo go to CIF? And if they did: How far would they go? Brayden seemed anxious about post-high school life. This was opposite my own experience at his age. I couldn’t wait to get out. In fact, I couldn’t wait so badly that I got expelled three weeks prior to senior graduation. At his age I was drinking like a maniac, getting arrested, getting tattoos at Hell’s Angels tattoo parlors in Ventura, chasing multiple girls around at once, flying around at raging punk shows, and generally being out of control.

Brayden is nothing like I was, and that’s a good thing. He’s soft-spoken, kind, thoughtful and respectful. If there’s one struggle here it’s that it takes a lot for him to talk. I often wonder at his inner life, the interior monologues and dialogues which may or may not be circulating in his mind at any given moment. I wish I knew. Like many kids his age, he is largely a closed book. A mystery. A transforming pupa.

*

When Britney and I started dating in August, 2022, Brayden was mostly out of her house, by then more or less fulltime living with his father. All her life Britney had wanted to flee Lompoc, but she’d gotten pregnant at 19 and had a son, so she was locked in. College had been an option, and living in San Francisco. Both these dreams faded away, replaced by a son she fell in love with. And, since we’d been together he’d been slowly but surely [emotionally] drifting apart from her, like PANGEA 200 million years ago, the continents breaking apart and moving away. This is normal, of course; a mother and son must separate. More than once my mom has commiserated, reminding Britney that they’ll reunite on the “other side” of his teens. My mom would know: I put her through the emotional wringer until I got sober at 27. For me it was a longer return home; Odysseus returning to Ithica.

Britney and I at one point cleared out Brayden’s old room. We moved his stuff, giving him what he wanted and selling the rest at a garage sale. She showed me his old drawings, some old journals, old toys. My own hallowed youth bubbled up inside. It was emotional. I knew it was profoundly hard for Britney to let go, accept that he was shifting away and adjusting, driven by inner and outer forces, pushed into the next phase of his existence, which didn’t include her as directly as before. How painful that must feel for Britney. I can only guess.

*

They made it to CIF. One loss and you were out now. Only a couple losses in the regular season—one technical due to pitching one pitcher too many times in a game—and a long string of wins, many of them brutal, like 11-1, 6-0, etc. Cabrillo seemed unstoppable. They prayed before games, and they possessed an incredible social rapport. As a team, they seemed psychologically glued to one another in a way I’d never witnessed before. It was sort of magical.

They won the first CIF game. The second game—both were at Cabrillo—was played against Atascadero. Cabrillo’s uniform was gold and yellow; Atascadero wore bright orange. Both teams were good. Really good. It was a tense game. Cabrillo was behind 2-1 but in the 6th inning (they only play to the 7th unless tied) Blake hit a solid one and got on base. Soon they scored and it was 2-2. It went into the 7th inning. Then the 8th. Britney, her stepdad and I stood by the fence opening closer to the batting area. Parents and the audience were shouting loudly. Intensity hung in the air. Whichever team lost was out, done.

Cabrillo did very well overall, but there were some errors made, too. Such is life. Everyone did their very best. Probably nerves were thin at this point. The tension was thick enough to cut with a machete. Everyone grew very quiet. In the 8th inning Atascadero got another run: 3-2 now. Cabrillo had the final bat. They couldn’t get on base. One out. Two outs. Third batter. One strike. Two strikes.

We all waited, heads shaking, eyes piercing the batter, praying in our minds, knowing that this pitch might be The Final Pitch.

And it was. Strike three. Three outs. Game over.

Cabrillo lost. They were out of CIF. It was all over.

The orange-uniformed Atascadero players rushed the field, jumping on each other and shouting like we’d seen Cabrillo do two dozen times themselves. But this time Cabrillo was silent. Everyone seemed to half-smile, hanging their heads.

“They did great,” someone said.

“Hell of a season,” I said, as well as several others.

“Heck of a game,” someone else added.

I felt shocked and a little sad, confused. How had Cabrillo lost? I realized they’d won so many games in a row that some part of me didn’t think they could lose. But they had. It was like when you were sure a story was going to be published and you brag to all your friends and then one day you open your email and it’s a rejection letter. “We regret to inform you…”

Britney wanted to try to talk to Brayden. I took our stuff—foldout chairs, blankets, jackets—and walked the opposite direction to get the car. Once in, I drove the 100 yards to the front parking lot and parked. I jumped out and found Britney standing at the diamond-link fence, watching the Cabrillo boys as they hugged and talked around the pitcher’s mound. The Atascadero boys were leaving, filing out in two’s and three’s across the right side of the field.

I realized many of the Cabrillo boys were crying, red-eyed. Ditto the coaches. And Britney. I scanned around and realized many people were crying, parents, girlfriends, siblings, etc. And it suddenly struck me: It was all over. Everything. Not “everything,” but this phase of life. Many of these boys were seniors. Brayden was a senior. Which meant that this would be the last game they ever played together on this field, it would be the last time they played high school baseball. It would be Britney’s last time ever seeing her son play high school baseball at this field. Ever. It was a sad, vibrant, intense moment, and, surprisingly, I felt it deep in my gut. I felt emotional myself. I’d grown to really enjoy baseball, and this specific team, and these players, and this field, and the family gatherings.

It was all finished.

Many of the boys—including Brayden—would go to Allan Hancock and try out for the team. But it wouldn’t be the same. Most of them would probably realistically drift apart and find their own friends and lives and directions. Some would transfer after two years to 4-year universities. It was the unknown mystery of the future, that unknown pearl we can never grasp until it ceases being the future and becomes the reality of the present.

I’m incredibly proud of Brayden, and of his team and all the players. And I’m proud of Britney for going to the games, showing such love for her son, and for allowing her son to grow and change and transform. We all have to grow up. It’s painful. But it’s necessary and inevitable.

I have a feeling that Brayden and the other players will never forget this season, and especially that final epic game against Atascadero.

They played their asses off, with fire in their hearts.

In many ways, I relate to them all. Baseball is both literal, physical and symbolic. It’s a symbol, a metaphor for swinging at the balls that life throws at you. Sometimes you hit and get out; sometimes you miss and strike out; sometimes you hit a nice, solid line-drive which gets you on base; sometimes you steal and get somewhere unexpected; sometimes others hit and get you around the plates to home; and sometimes you hit that glorious, effervescent homerun and get to jog around the plates in total ease and glory.

Either way: Baseball is life.

Really appreciated this. As a dad, I hope to remain flexible to the worlds my kids open up to me. For now, I'm enjoying sharing T-ball with my son. But if it's not his jam later on, that will be cool, too.

Baseball is an intellectual's game. Lots of time between innings and between pitches for good conversation, too.

Oh my goodness! What a great article showcasing all of the intense emotions of being a baseball parent and player , none of which I would trade for the world.

Just as great as the bond developed between the players is the bond developed between the parents. I have built friendships for life being on those sidelines and let’s not forget some of the most amazing nicknames to ever be formed 😎.

Thank you for writing about this Cabrillo team. Those young men were impressive beyond words and I can’t wait to see how far they all go in life…whether it’s on a sports field or not.