Ernest Hemingway: Genius Shithead

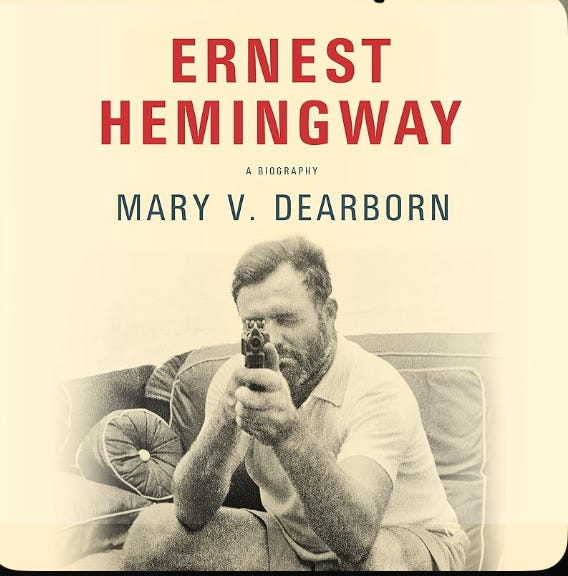

Fiction Based on Mary Dearborn's 2018 Hemingway: A Biography

*This is a work of fiction. I pulled largely from my reading of Mary Dearborn’s biography from 2018. Some of it is flatly made up by me. I was having fun with this. I hope you enjoy it. Comments open.

~

“So I’m a secretly gay narcissist who hates women and takes everyone around me for granted. Is that it?”

“Not only that. She says all your work—minus, she says, The Sun Also Rises, the short stories The Snows of Kilimanjaro and The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber and the novel For Whom the Bell Tolls—was more or less hack work; terrible writing that everyone just fawned over because of your good looks and charisma.”

~

Imagine it’s 1941 and you’re in Havana, Cuba, and, taking a break from your writing—you came here with your wife for a two-week vacation—you decide to walk into a bar called Sloppy Joe’s, famous even then due to the fact that one particular person, the famous author Ernest Hemingway, goes there often.

You are married to a woman who’s mother is still good friends with Pauline Pfeiffer—Hemingway’s second wife—and therefore you know all the inside gossip and drama about Hem that isn’t in the media.

You are a 31-year-old unpublished writer—not yet any published novel, though you’re working on one—and you and your wife, Linda, have been married for two years.

You walk along the road towards the bar a quarter mile away. The sea is brimming with effervescent life, sizzling in a slightly stormy breeze, the ocean a wild green-gray-blue color. Seagulls yawp loudly, flying just above the waterline. You’re wearing beige cotton pants, brown hiking boots and a tucked-in white button-up collared shirt, the top three buttons undone. It’s early fall, still an Indian Summer feel, fairly warm but just beginning to cool down.

Everywhere you see here you are reminded of poverty. It reminds you of certain places in Mexico. Old, poverty-stricken men lounge around in the weeds off the road or else on the porches of homes with tin roofs which are crumbling because they can no longer take care of them. The green weeds in the fields are long and tall and bend in the wind like devoted aliens doing exercises all at once.

You stand in front of the bar. It’s a medium-sized place, dilapidated, with an ancient bamboo door. It says SLOPPY JOE’S, SINCE 1912 above the bamboo door in old, faded crimson letters.

It’s dark inside, not completely but it feels more or less like some kind of safe, unhealthy womb. The whole place is 600, maybe 700 square feet. Rectangular wooden tables up front, full of scratches and pen markings from over the decades. Music is playing, some jazz ballad.

The bar is long and straight and flat. An old man stands behind the bar, filthy white rag over his shoulder, hands so bulbous and veiny and red they look like gloves, almost non-human. You walk up to the bar, nod to the bartender, and take a seat.

“What’ll you have, sailor?”

“Whiskey sour. Neat.”

The bartender nods and starts the drink. It’s quiet in here and, you think for a moment, maybe you could even write here, work on your novel.

When the bartender brings the drink, spilling onto the bar raising the stink of whiskey up like a sadly blooming fresh flower in spring, you set a ten-dollar bill, crisp, clean and brand-new, onto the bar.

“Say,” you say, bringing the drink up to your lips and taking a little preemptory sip (the whiskey burns beautifully going down your throat). “When does Papa come in here usually?”

The bartender, his eyes slightly twinkling, and yet with a slight look of irritation or fatigue, tells you.

~

Just like clockwork, at exactly 2pm, the door to Sloppy Joe’s creaks open. There he is. Ernest Hemingway.

He’s bulkier than you remember from the photos you’ve seen from your stepmom and from what you’ve seen in the media. He’s poorly dressed, wearing a pair of stained brown shorts. An old wife-beater barely conceals the absurd amount of thick black body hair he has on his arms (which are long and thick and huge). Six foot tall. He must clock in at 210, easy. Heavyweight. He is barefoot.

“How ya doin, Sporty?” Hemingway says, grinning, shaking the bartender’s hand familiarly. His voice is higher than you expected, but you had heard that somewhere. Not high-pitched…just not as deep as you’d expect from a man of his stature, size and history. His skin is very tanned from the sun. Only four or five feet away from you, you can smell the sea and the salt.

“Well, my friend,” the bartender says. “How goes?”

Hemingway shrugs, “Been out on the Pilar all day. Caught two swordfish. One was just under 900 pounds.”

“Not bad,” the bartender says, smiling. “Not bad at all.”

Hemingway slaps the thick laminated bar top and exclaims, “Gimme a Vermouth on the rocks, Jimmy.” He then taps the bar repeatedly.

After the drink is made and placed in front of Hemingway, the bartender (“Jimmy” or “Sporty”) looks down at you and, pointing with his beefy index finger, he says, “You gotta fan.”

As a burst of embarrassment and shame slice into your gut, Hemingway glances down the bar at you, says “Cheers” and takes a hefty slug of his drink.

You nod and finish your fifth whiskey sour. “Say Sporty,” you say, “How about another one.”

Hemingway’s voice booms down the bar at you: “Only I can call this man Sporty, kid. You got that?”

“Sorry,” you say. “Really. I’ve just had a few too many too fast. My apologies. I’m a huge fan, Mr. Hemingway. And…” you try to hold yourself back from speaking the next words out loud, but alas you can’t help it. “My wife, Linda, her mother is a close friend of your ex-wife.”

Hemingway fully turns his head and body now towards you in an intimidating, forceful gesture which sends a shiver down your spine. Hem takes a massive glug of his drink, killing it. His eyes glued to yours now, without averting his gaze for a second Hem says, “Sporty.”

When the new drink is placed in his hand Hem says, “Which one, dare I ask?”

Your new whiskey sour sits in front of you and you lift it to your parched lips and sip. The ice (you now asked for ice) clinks against the glass seeming too loud in your anxious mind. Jesus. I’m in Havana, Cuba, in the famous bar Ernest Hemingway frequents…and now I’m actually TALKING to Ernest fucking Hemingway.

“Pauline Pfeiffer,” you say.

He sighs, drinks, and, slapping the bar with his balled fist, he says, “Everything that bitch said was a lie.”

Vintage Hemingway.

“What is it, then, that you think you know about me, huh? Let’s just get it out of the way.”

You say, “Well. I mean you’re a brilliant writer, of course.”

Hemingway looks away for a moment, glugging again. He twists the tumbler in his hand. “Brilliant, huh? Maybe. They loved The Sun Also Rises and the short stories…but Green Hills of Africa and To Have and Have Not…not so much.” He sighed again, as if speaking alone in his room only to himself, gazing, perhaps nostalgically, into his glass. “But, at least there’s To Whom the Bell Tolls. Sold over 500,000 copies.”

“It’s an excellent book, Mr. Hemingway.”

Ernest, jolted out of his silent reverie, and, once more twisting the tumbler, says, “Reviewers seemed to like it. Clearly readers did. What did you say your name was, Sporty?”

“Sean. Sean Moore.”

“How old are you, Sean Moore?” Hemingway asks.

“Thirty-one.”

Hemingway slurps his drink shaking his head. “That Vermouth really kicks, Jimmy!” Hem says, “Thirty-one. Well I’m 42, my friend. Old. Over the hill, probably.”

“Forty-two isn’t old, Mr. Hemingway…”

“Call me Ernest.”

“Ernest…forty-two isn’t old.”

“Wait until you turn 42. You’ll think differently.”

“Maybe.”

A silence ensues and during it you both drink from your glasses. Hemingway steps down the bar getting closer to you. “So, Sean. What are you doing in Havana?”

You shrug and tell Hem about living in Manhattan, trying to be a writer, being married, and needing a vacation to work on your first novel.

“You got a title yet?” Hem asks.

“A working-title so far is The Jumping Off Place.”

“What’s that from?”

“The Alcoholics Anonymous Big Book.”

Laughing, ordering two more drinks, one for him and one for you, Hem says, “Doesn’t seem like the AA is working for you.”

“I’m on and off. I had almost four years sober at one point.”

Hem tilts his head and says, raising his new glass, “Well congrats to sobriety.” He sips and then says, “Sobriety never worked for me. Only when I’m writing.”

“I know. The stories of your hard drinking are infamous.”

“The tales are mostly all hogwash. Lies. Fibs. Myth. I didn’t drink that much.” Hem looks away and then back and said, “Well. Alright. I did drink a lot for a while. It was the times. The 1920s, Paris. We all drank.”

You say, “Well you were never like Fitzgerald. That’s for sure.”

Hem’s eyes twinkled for a moment and then he seemed lost in a memory. “Good old Scott. He was a good man. A terrible, awful rummy, of course. Never seen a worse one. Acted like a petulant child. He once face-planted at dinner. We just left him there. Sad case. He and Zelda. She was batty as a fruit fly. Most writers back then were.”

“Can’t argue with that,” you say.

Suddenly Hem turns to you and, with his considerable penetrating eyes, says, “Tell me all the gossip. About me, I mean. Everything you know from your…wife isn’t it?”

“My wife’s mom. My stepmom. Denise Cowler.”

“Denise Cowler. Never met her. But the name rings several bells. Ok. Carry on. Tell me the worst of it.”

You feel several pairs of prying eyes on your back.

“Well,” you say… “I dunno if that’s such a great idea, Mr….Ernest…I mean, you know, most of it’s probably just hearsay, anyway, and really, why would you want to…”

Hem slams his empty glass onto the bar top. “Tell me, kid. Sean. Tell me. I’ll help you with your novel if you want. Just tell me.”

You order two more whiskey sours. You need two. By now you’re more than 70% drunk, you’d guess. Still mostly in command of your faculties but definitely feeling it. The booze feels like a warm, satisfying snake coiled up in your solar plexus.

“And don’t lie to me, Sean. I’m an expert in knowing when people lie. Tell me the truth. Speak truly, son. Don’t worry. I can take it.”

“How about I start out with a minor one…”

“No!!!” Hem says, eyes wide and angry now, like a bull’s. “Tell. Me. The Worst. Shit. Go on.”

“Well,” you say. “She says you’re a womanizer.”

Hem laughs, snorting into his drink which is at his lips, tipping into his mouth. “That bitch. All women are bitches. Can’t trust a damn one of em.”

“She says you ran out on Hadley and then did the same to Pauline and that you didn’t care about anything other than yourself; not the marriage, not the kids, just your writing.”

“That’s horseshit,” Hem says. “What else?”

“She says you’re one of the most terrible, ‘rancid’ narcissists she’s ever known. She says you lived off rich women with big trust-funds and you never could have survived and made it as an author without them. She says you were cruel to Hadley and Pauline, making them take care of the kids all the time while you went off hunting or writing or adventuring or fishing. It was ‘always about Hemingway,’ she said.”

Hem looks down at the bar. “More.”

“Listen…Mr. Hem…Ernest…maybe this isn’t such a good idea….”

“You say that one more time,” Hem says, “And I’ll knock your fucking block off!”

“I’m sorry.”

“Carry on. Tell me.”

“Well. She said you took women for granted. Used them. Abused them. She said she even wondered if you might be a sociopath. And then there is the sexuality…”

“What do you mean?” Hem looks at you dead in the eyes again. He’s two feet away, standing at the bar. Everyone is listening with rapt attention.

“Basically, that you overcompensated. You and Fitzgerald in the mid-1920s in Paris. That old gay man who wanted to bankroll your trip through Europe for a year and you almost did it. The boxing and hunting and fishing and bullfights; she felt like all that over-the-top macho shit was a sort of Freudian mask for…well…for…”

“Go ahead, kid. You can say it. Don’t fret. I won’t hit you. Just say it, kid.”

Swallowing, you say, “…a mask for…homosexuality.”

Hemingway finishes his drink. Sporty brings him another. You swig from your whiskey sour. You feel the warm, poisonous liquid sealing your innards like a beautiful woman gently rubbing your belly.

“Goddamn women. Bitches every single fucking goddamn one. Every ONE!”

“What else?”

“Are you sure…”

“WHAT ELSE???!”

“She said you screwed over every writer who ever helped you become a published author and get famous. All of them, from Sherwood Anderson to Ezra Pound to Gertrude Stein to John Dos Passos to F. Scott Fitzgerald and more. Every single one. The rule was, my stepmom claimed, ‘If they helped Ernest in any way, he took them down, either in his writing or through media gossip.’”

“So I’m a secretly gay narcissist who hates women and takes everyone around me for granted. Is that it?”

“Not only that. She says all your work—minus, she says, The Sun Also Rises, the short stories The Snows of Kilimanjaro and The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber and the novel For Whom the Bell Tolls—was more or less hack work; terrible writing that everyone just fawned over because of your good looks and charisma.”

“I see,” Hemingway says, an edge of bitterness in his voice now. “What else?”

“She says you’re a terrible, spoiled rich boy whose parents did everything for and yet you still victimize yourself and blame and resent your mother. She says you’re a ‘filthy, no-good’ communist because of your support of the republicans in the Spanish Civil War, and because your only political vote, in 1920, was for the imprisoned socialist Eugene V. Debbs.”

Drinking, Hem pulls back and says, “Doesn’t this woman—Mrs. Cowler—have any decency? Doesn’t she have any respect or moral values?”

“Remember, Hem, Ernest, she’s my wife’s mother. She gets all of this from your ex-wife, Pauline. Don’t shoot the messenger.”

“Listen, Sean. I have supported Hadley and Pauline and all my kids financially from the beginning. Besides, both women have massive family trusts. They’re fine. My children are fine. I hunt and fish and box and watch bullfights because it’s all ART, goddamn it, and because it’s all stuff I truly love. Can you understand that?”

“Sure I can, Ernest…”

“She says I’m a communist and a hack writer. I was pro-Nationalist in the beginning in Spain. But then I changed. I hate fascism, all those punks, Hitler, Mussolini, Franco. Stalin, too. They’re all deranged.” He paused, drinking. “And sure, yeah, I was rough on some of those women…but by god they were also rough on me!! I’m just a man. I am ONLY a man! I can only take so much. I’m tough but I’m also sensitive; there, I said it. Write that down cause you won’t ever hear me say it again. I’m sure she also thinks I’m an alcoholic and a depressive, that I have ‘shell-shock’ from The Great War…all that shit, right?”

You nod slowly and carefully.

“Goddamn it. Women. Unbelievable. You give em everything, your whole life, and it’s still never enough. Bitches. Starting with Grace Hemingway, my own manipulative, controlling mother! Blast them all!”

Hemingway glugs. A silence falls. Sporty brings new drinks.

“Life is hard no matter how you slice it, Ernest.”

“Ain’t that the truth. I’ll tell you. I’ve been shot multiple times. Been through several wars. Many women. Heartache. I never even went to college—cause of my bitch mom—and look how far I got! I didn’t need some degree hanging on my wall. Now the colleges all churn out these writing degrees as if anyone can write. It’s all shit nowadays! You’ve got to go back to the Greek classics, or at least to Dante for anything worthwhile. And my own work, some of it, of course.” He stopped talking for a moment and sipped his next drink. “What do you think of me, Sean? Tell me the truth. Like I said before: I’ll know if you’re lying, son.”

“I think you’re the most brilliant writer of our time. The twentieth century. I think your work—much of it, anyway—will stand the test of time and will still be read in 200, 300 years. I think you’re a genius.” Here you pause a moment, steel yourself, drink, and then continue. “I also think you’re probably an alcoholic. You suffer, clearly, from serious depression. You probably go through secret periods of suicidal ideation. Maybe you even make plans. I think your sexuality is likely complex. Like the way you’ve always been obsessed with hair, both male and female, and the way your mom dressed you up like your sister as a child. I think you probably resent your father for being weak and your mother for being too independent and strong. I think with women you always mean well but you’re ultimately incredibly selfish and needy. You’re a man of your time. You came of age in the 1920s and that was a time when women were subordinate to men, and when men were revered while women were denounced. I think you’re in the end ultimately a good and decent, moral yet complex and confused human being, a dark genius who has plenty of demons.”

Hemingway sighs and sips his drink. You follow suit. You lost count of how many drinks either of you had.

“You wanna go outside and box?” Hem says.

He looks at you sincerely.

You laugh. “You’re joking, right?”

“Dead serious. I have gloves behind the bar.”

“No way, Ernest. You’d kill me.”

“C’mon, kid. It’d be fun. You have a decade on me. You look strong.”

“I’m honored, Hem. Ernest. Really, I am. But I’ll pass.”

Hem shrugs and says, “Suit yourself.”

Then, out of nowhere, Hem’s massive, hairy arm flails out unexpectedly and his giant fist connects with your face.

You go down.

~

An hour later you come to. You’re on the floor in the bathroom behind the bar. Your head aches. Standing, you see you have a black eye. You stare at yourself in the cracked mirror. You wash your face gently with cold water from the faucet. Then it hits you, all of it. Ernest Hemingway. You got punched out by Ernest fucking Hemingway. You smile, despite yourself. You can’t wait to tell everyone you know. You realize this needs to somehow be incorporated into your nascent novel.

In the bar everyone claps. Hemingway is gone. You pay your tab. Sporty grins at you. No one says a word. You walk across the bar feeling all the eyes. You open the bamboo door and walk outside and it’s past 5pm now and cold and there’s an easterly wind blowing. The waves crash lightly. You feel young and alive and lucky.

Love this. Did my senior paper on women in Hemingway novels. It was a very short paper.

Bravo. This was delightful. A really fun and creative piece of writing. Strange timing as well because I was just rewatching that Hem movie 'Papa' on Amazon prime a few days ago. Your version of Hem is similar to the one in the movie.