***NOTE 9/27/24): This essay was originally published on 1/19/2023. At the time it went out to 247 subscribers yet received almost 1,000 views and drew a lot of new subscribers, free and paid. I cleaned it up a bit for my current (much bigger) audience. Rereading it now, almost a year and nine months later, I still think the essay is very strong. I do feel like I overused the contentious word “Woke,” and I do sense an underlying feeling of anger which I no longer feel to the same degree. And, to be clear: I see this as a problem very much occurring on both political sides, it just strikes me as culturally more obvious on the far-Left. (And when I say ‘far-Left I don’t mean the greater Democratic Party, though they have adopted some of the new language.) Agree with my views on this or not, I think the bigger point is that language has changed radically over the past decade, and the reasons for that are not necessarily benign.

~

George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language”

A Revisit of the Classic Essay for 2023

This 15-ish page classic Orwell essay—published in 1946 when Orwell was 43, four years before he died—says everything that needs to be said about Identity Politics (or whatever the hell you prefer to call it, since the new trend seems to be claiming that the word ‘Woke’ itself carries no meaning; whatever you want to call “it” the point is that there is an identifying “it” to be commented on).

It's funny, sad, absurd and terrifying that the progressive left used to absolutely cherish George Orwell, an avowed anti-Totalitarian and Social-Democrat, and yet they have now basically (and quietly) shifted this narrative, attempting of all things to turn Orwell himself—and therefore his ideas—into yet another “Republican talking point.” I won’t go into the specifics of why the contemporary “progressive” left has lost their minds, how they’ve become the very thing they claim to hate, how Animal Farm and 1984 describe not only the far-right wing of America but the far-left. That, in my view, is so patently obvious to anyone still using a functional brain that it need not even be explicated.

In “Politics and the English Language” Orwell discusses many concepts, all of which have to do with what he perceived at the time as the decay of the Anglo-Saxon writing tradition. One thing I love about Orwell is his no-bullshit, direct, straight-from-the-hip, concise and almost punch-you-in-the-face manner of writing. He tells you like it is. As with any writer, I do not agree with every single thing he writes. But I do think, right or wrong as any case may be, he was certainly one of our most honest writers.

In the essay he rants eloquently about the overuse of “fancy” or “pretentious” or “glittery” language (all except “pretentious are my words). He complains about the then-contemporary lack of “precision” and “clarity” (his words). The overuse of Latin and Greek words get a harsh grilling. Nonsensical, trite, overused cliché metaphors and similes get a beating. Worn-out metaphors; mixed metaphors; pre-fabricated words strung together for ready-use; the lack of self-honesty around any writer’s inherent political bias; etc. Vagueness gets a sock to the face; he prefers “concreteness” and “detail” over general, lazy assertions which cannot easily be seen, understood, identified, defended. Bad, useless diction. Changing simple words or concepts into their opposites.

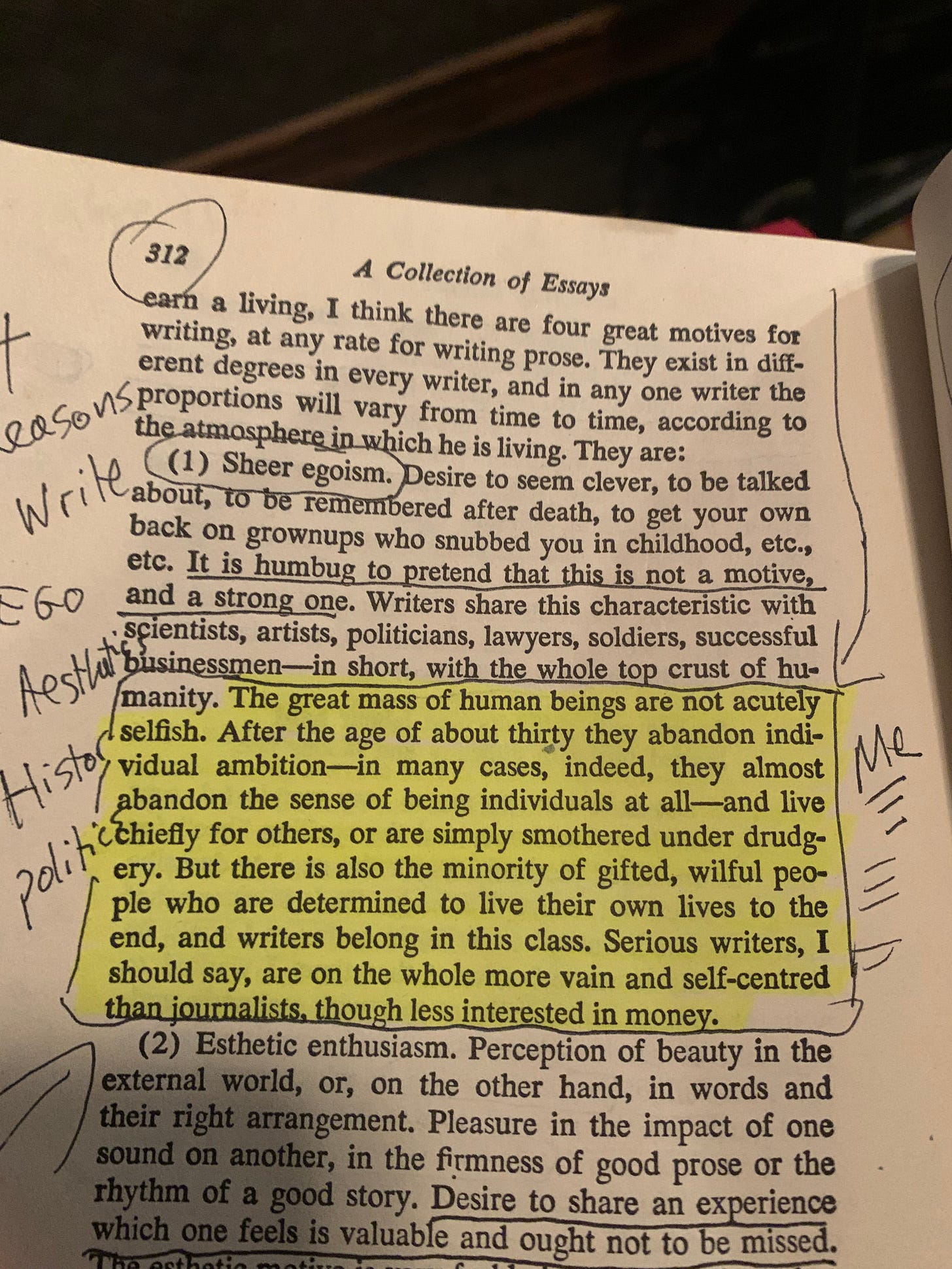

Orwell drums up (brilliantly) Six Writer Questions: “A scrupulous writer, in every sentence that he writes, will ask himself at least four questions, thus: 1. What am I trying to say? 2. What words will express it? 3. What image or idiom will make it clearer? 4. Is this image fresh enough to have an effect? And he will probably ask himself two more: Could I put it more shortly? Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly?”

He complains about “euphemisms” and the overuse of “the not-un formation,” as in “Jimmy was not unable to write well.” Just say:” “Jimmy wrote well.” Why the additional glittery ornament? Why the flashy added words? To try to sound more intelligent? Really writers who do this more often sound pretentious and insecure. Orwell writes about what authors are often trying to say consciously, and how that often contradicts what comes out on the page unconsciously.

He writes about the Six Rules of Writing:

“One can often be in doubt about the effect of a word or a phrase, and one needs rules that one can rely on when instinct fails. I think the following rules will cover most cases”:

1. Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

2. Never use a long word where a short one will do.

3. If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

4. Never use the passive where you can use the active.

5. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

6. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

###

Contemporary Times and “Politics and the English Language.”

In the essay Orwell makes several astute clarifying statements about bias and political agendas in writing. This is the end of the first paragraph of page one:

“It follows that any struggle against the abuse of language is a sentimental archaism, like preferring candles to electric light or hansom cabs to aeroplanes. Underneath this lies the half-conscious belief that language is a natural growth and not an instrument which we shape for our own purposes.”

Here’s a proper quote from the essay on clarity: “If one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step toward political regeneration: so that the fight against bad English is not frivolous and is not the exclusive concern of professional writers.”

Here is where the second decade of the 21st century comes in a la Wokeism/Identity Politics:

“Many political words are similarly abused. The word fascism now has no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable’. The words democracy, socialism, freedom, patriotic, realistic, justice have each of them several different meanings which cannot be reconciled with one another. In the case of a word like democracy, not only is there no agreed definition, but the attempt to make one is resisted from all sides. It is almost universally felt that when we call a country democratic we are praising it: consequently the defenders of every kind of regime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they might have to stop using that word if it were tied down to any one meaning.

“Words of this kind are often used in a consciously dishonest way. That is, the person who uses them has his own private definition, but allows his hearer to think he means something quite different. Statements like Marshal Pétain was a true patriot, The Soviet press is the freest in the world, The Catholic Church is opposed to persecution, are almost always made with intent to deceive. Other words used in variable meanings, in most cases more or less dishonestly, are: class, totalitarian, science, progressive, reactionary, bourgeois, equality.”

It's profound when you consider the fact that this was written in the 1940s. It could have been published in, say, Reason Magazine right now, in 2023. This is what is happening in the “progressive” left. Everything represented by the Enlightenment for hundreds of years—reason, rational thinking, science, actual human progress, social justice, equality—is and has now for a decade been being slowly, methodically dismantled.

So-called “antiracism” groups all black people into one group, because obviously they all look, act, think and talk the same. Ditto “Latin-X” people, most of whom loathe that very term. (Denying the plethora of different, conflicting, variable groups and subgroups within the broad context of “Hispanic” or “Latin.”

Clearly, all “white” people are exactly the same. Forget that up until the mid-late twentieth century, and for thousands of years prior, ethnic groups such as the Irish were treated almost as badly as slaves. (Read Gordon Wood’s “Power and Liberty” for more on this. White indentured servants were beaten, killed, raped, pushed into forced labor, and were even literally bought and sold at auctions.)

Science, as anyone who’s paying attention grasps, is struggling for survival right this moment. Papers which might not exactly tow the left academic line are either rejected, condemned or censored. The tribal explosion of rage around Covid masking was a great example: Many on the right were living in LaLa Land around Covid protections, and yet on the left it was just as bad when the vaccines were available and kids were still being masked and held away from school and everyone on the left began “signaling” support for their tribe by wearing masks when outside walking alone or when alone in their car, not because it was “based in Science” (it wasn’t) but because Orange Man Bad, Biden/Left good/moral/correct.

Or how about the trans “conversation.” Biological sex is now “a social construct.” Not only can you be any of 1,000 genders, but you can be any sex (or non-sex) you choose. There are literally zero biological differences between men and women despite the most blatant, glaring, obvious evidence against this. What the progressives do is take old words like “science” or “justice” or “race” or “racism” or “sex” or “gender” and crack them open, hollow them out of any meat (meaning), flip them upside down, and tell you to your face that you don’t understand the fundamental nature of reality. In other words: It’s Millennial madness. Gen-Z madness. Insanity. Gaslighting.

Orwell again: “…words and meaning have almost parted company. People who write in this manner usually have a general emotional meaning – they dislike one thing and want to express solidarity with another – but they are not interested in the detail of what they are saying.” (Underlining is mine.)

The above quote nails my point precisely: Radical writers/thinkers/revolutionaries—whether on the left or right, but especially on the left—speak mostly nowadays not from science or fact or data, not even from any place of rational, serious argument, but rather from a deeply emotional (read: angry; tribal) core. This anger is rooted in fear. The fear stems from being terrified of being rejected by their tribe. And like the last line of the quote says: These writers are not curious at all about “what” they’re actually saying; they only care about fulfilling their tribal, ideological role. In other words: They aren’t thinking. The requirement for Wokeism/Identity Politics is to turn your brain off. Tow the line.

This nails the contemporary leftist “thinker”:

“When one watches some tired hack on the platform mechanically repeating the familiar phrases – bestial atrocities, iron heel, blood-stained tyranny, free peoples of the world, stand shoulder to shoulder – one often has a curious feeling that one is not watching a live human being but some kind of dummy: a feeling which suddenly becomes stronger at moments when the light catches the speaker’s spectacles and turns them into blank discs which seem to have no eyes behind them. And this is not altogether fanciful. A speaker who uses that kind of phraseology has gone some distance toward turning himself into a machine. The appropriate noises are coming out of his larynx, but his brain is not involved as it would be if he were choosing his words for himself. If the speech he is making is one that he is accustomed to make over and over again, he may be almost unconscious of what he is saying, as one is when one utters the responses in church. And this reduced state of consciousness, if not indispensable, is at any rate favourable to political conformity.”

I LOVE the above quote, especially when applied to our time now. The first line, indicating all the old, safe, staid, overused, mechanical words, is perfect. Just replace these 1940s words with words/phrases such as these: “400 years of oppression,” “antiracism,” “racism,” “slavery,” “Whiteness,” “Blackness,” “Republican talking-point,” “Fascism,” “cultural appropriation,” ad infinitum. It’s incredibly obvious most of the time that the vast majority of people (especially young elites in Washington, mainstream journalists, etc) who fire off these lazy, anti-intellectual, pop-culture, often non-factual, non-data-driven, ahistorical words and phrases care nothing at all for what they might actually mean…or more to the point not mean. Mostly they have lost any sense of “meaning” now anyway. As I said earlier: They’re glittering shells of emptiness, performative squeezed-out bladders with nothing actually there except pure air. (Or, to quote Orwell himself: “Pure wind.”)

Orwell once more:

“The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms, like a cuttlefish spurting out ink. In our age there is no such thing as ‘keeping out of politics’. All issues are political issues, and politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred and schizophrenia. When the general atmosphere is bad, language must suffer. I should expect to find – this is a guess which I have not sufficient knowledge to verify – that the German, Russian and Italian languages have all deteriorated in the last ten or fifteen years, as a result of dictatorship.

The line: “When the general atmosphere is bad, language must suffer.” Yes. The general atmosphere has been bad (that’s putting it lightly) for the past decade. The degradation of language has been happening slowly, ruthlessly, mostly from the left, and now faster than tech can keep up with.

This quote is for those on the left who are always yammering about how language “always has and always will naturally change.”:

“I said earlier that the decadence of our language is probably curable. Those who deny this would argue, if they produced an argument at all, that language merely reflects existing social conditions, and that we cannot influence its development by any direct tinkering with words and constructions. So far as the general tone or spirit of a language goes, this may be true, but it is not true in detail. Silly words and expressions have often disappeared, not through any evolutionary process but owing to the conscious action of a minority.”

And this is exactly my point. What we have now is absolutely NOT a natural evolution in language, but rather an unnatural devolution and decay of language very purposefully provoked and carried through radical leftist young people who have somehow, incredibly, captured major institutions to varying degrees such as The New York Times, the Washington Post, CNN, NPR, etc. Has language always consistently changed naturally over time? Yes. Absolutely, and since the dawn of the first use of language perhaps 50,000-150,000 years ago. But it hasn’t always changed like this, via a tiny percentage of the population doing it with a clear, biased political agenda done with the intent of altering reality in their ideological favor. No. That, at least to this startling degree, is new.

One final Orwell quote and then a parting note from me:

“Stuart Chase and others have come near to claiming that all abstract words are meaningless, and have used this as a pretext for advocating a kind of political quietism. Since you don’t know what Fascism is, how can you struggle against Fascism? One need not swallow such absurdities as this, but one ought to recognize that the present political chaos is connected with the decay of language, and that one can probably bring about some improvement by starting at the verbal end. If you simplify your English, you are freed from the worst follies of orthodoxy.”

Again: The decay of language is a clear sign of the state of our social and societal sanity. We’re not doing well. Ironically, in the United States, this doesn’t stem from the “evils of Capitalism,” but rather from the victory of capitalism. In 2023, Americans as a whole are so wealthy, so privileged, so incredibly lucky, and we’ve spoiled two generations now to such a ridiculous degree, that we have young people who are now so self-indulgent, narcissistic and entitled that they simply have to make up fictions to fight against. Civil Rights fighting in the 50s and 60s took care of most of the major battles against the legacy of actual racism.

The first and second wave women’s movements ineradicably changed the culture much more in favor of women than ever before. I’m not saying everyone is rich in America. Obviously this is not the case. (Look at inner urban poverty all over the country; the working-class Midwest; the gap between rich and poor generally.) My point is: Generally speaking, the kids are bored and privileged and so…why not antiracism? You get to scream and yell and destroy people’s lives. You don’t have to argue or defend your views. You don’t even need to read or form ideas. You just sit back and Tweet about the latest Old White Man and how terrible he is, how “late capitalism” is falling apart, how we’re going to soon be living in our Utopian Socialist Cooperative called The United States of AntiCapitalism.

*I want to make one final brief comment. I feel compelled to add this. I am not and never have been a Republican. Every single vote I’ve ever cast in my entire voting life (which started in 2001) has been for a Democrat, whether local, state, or federal. I have rarely watched Fox News, and the few times I did were basically out of pure morbid curiosity. Up until about a year-and-a-half ago my main sources of news were: The New York Times; The New Yorker; the Washington Post; sometimes Harper’s Magazine. If you looked at my history online until the past year you’d see a guy who more or less sounded close to progressive.

For the record I think Trump is a malignant narcissist and a racist; I don’t only say racist due to his presidency but due to his long, very public history leading up to his presidency. For the most part I do not believe in major Republican values. I think the government should sometimes help. I am for at least moderate gun restrictions, especially for automatic assault-rifles which can be used for mass shootings. I think our private for-profit healthcare system is a dismal joke and needs desperately to be reformed. I voted for and liked very much Obama, though I criticized some of his policies as well.

In general, I still believe in the Democratic party as a whole, from a historical perspective. Yet the Democratic party has been largely hijacked by progressive Identity Politics. And social justice warriors are NOT progressive; they’re regressive. They’re anti-intellectual. Anti-science. Anti-fact. Anti-commonsense. Anti-human, even. Not to mention racist, stupid, and ignorant beyond the pale. The answer to our problems right now is neither far-right nor far-left populism. It is either a return to something like moderation and political adulthood (unlikely but possible) or something completely futuristic and startlingly new.

Either way it’s not going to be the current status-quo. I am a free-thinker, an individual, someone who holds off on answering how I feel about something until I truly read and think deeply about it.

Orwell can be our guide right now. We are in the depths of the thickest cultural forest we’ve ever known in modern times. His words burn a bright hole through all the jungle to the outside world, open and free and beautiful.

Can we follow that beam of light to ultimate freedom?

This is stunning and refreshing.

A highlight for me in one of the quotes:

“The appropriate noises are coming out of his larynx, but his brain is not involved as it would be if he were choosing his words for himself. If the speech he is making is one that he is accustomed to make over and over again, he may be almost unconscious of what he is saying, as one is when one utters the responses in church. And this reduced state of consciousness, if not indispensable, is at any rate favourable to political conformity.”

Taking us to church!

Those closing three lines, wow.- “… the depths of the thickest cultural forest we’ve ever known in modern times… a bright hole through all the jungle to the outside world, open and free and beautiful.”

Thank you for extending “that beam of light to ultimate freedom,” Michael. These are imperative perspectives.

I hear a lot about Orwell but I was never exposed to him and truthfully have not made the effort. I appreciate you laying his writing out and applying it to today's cultural madness. Your point about today's youth not having any real problems is spot on. My best friend and I talks about this all the time. Life is so easy for them (generally speaking) so they make shit up as they go. It just seems like everyone wants to take part in the oppression Olympics or be the language police. If I hear my daughter use the term "social construct" one more time I'm going to explode. Our last heavy Convo was that I didn't believe that we all need to be reduced to a group & that we are all complex individuals etc...her response started w "individulism is separate...." This is where I stopped listening. Anyway, great write up. I plan on reading it multiple times so I can present a rational argument to all the crazy left progressives I'm surrounded with.