Gustave Flaubert: Man of Letters

On Sentimental Education (1869)

~

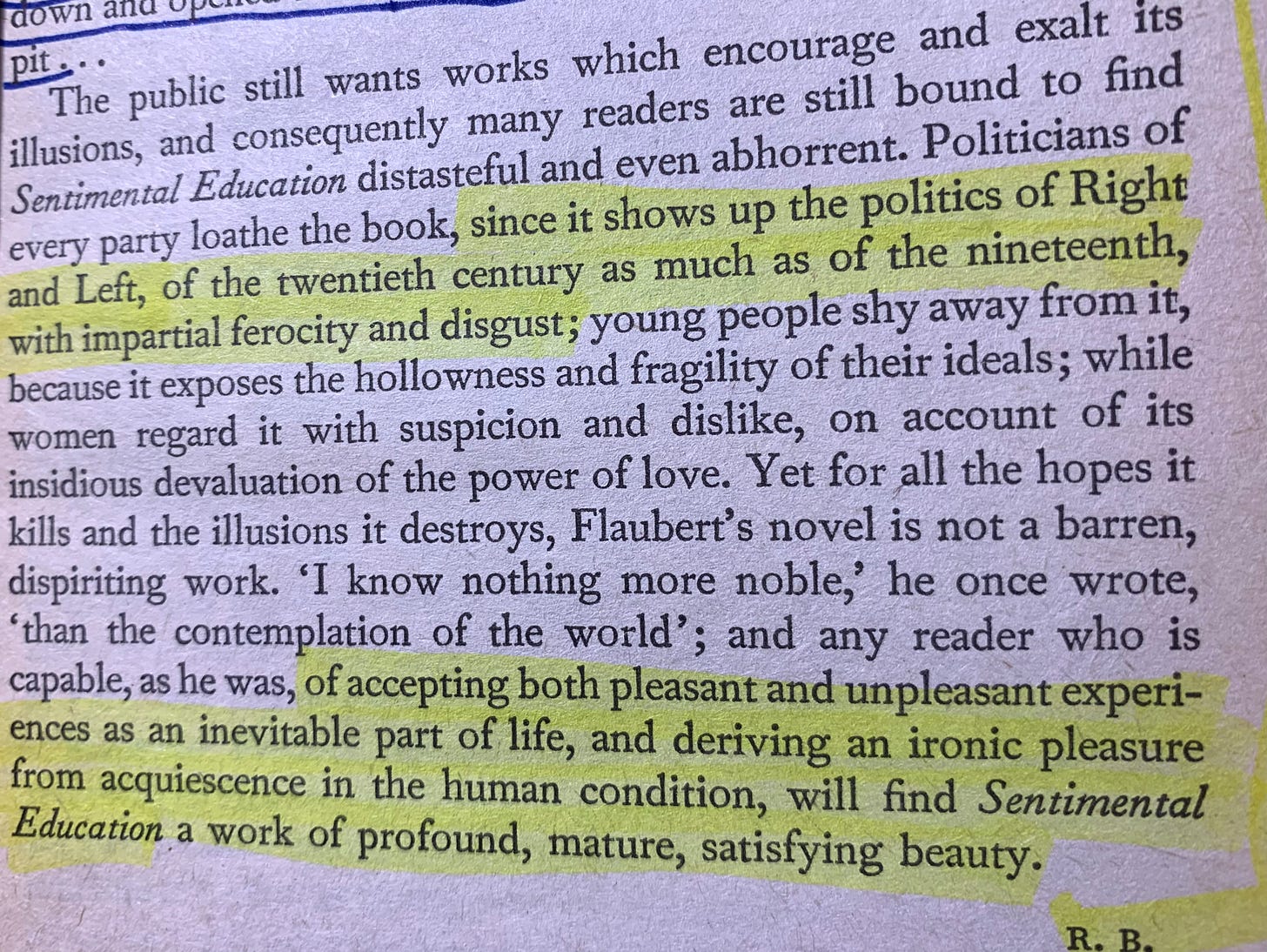

I recently finished reading the French author Gustave Flaubert’s (1821-1880, died at age 58) 1869 masterpiece, Sentimental Education. Needless to say: It blew me away. In general, I’ve long been a fan of reading 19th century writing—or 20th century at latest—because I’ve found, frankly, that the more modern you get with literature, the less “literary” it seems, and the more mired in obvious, blatant political ideology, some sort of hyper-moral agenda, and tribal stupidity it tends to be. Easy and lovely exceptions to this are authors such as Zadie Smith, Ottessa Moshfegh, Elif Batuman, the late David Foster Wallace, Jonathan Franzen, Junot Diaz, Chuck Palaniuk, Michael Chabon, Margaret Atwood, and others.

What fascinates me above all else in Sentimental Education is the incredible, profoundly nuanced and complex and layered plotwork. Flaubert is a master at plot. If you’re an aspiring writer right now, in 2023, read this book because it’ll teach you in a masterly manner how to concoct a believable, tension-filled plot.

The story is too complex to summarize with any real accuracy in this one brief post, but the basic idea is the following. Frédéric Moreau is the young male protagonist. He flees his rural home in France for Paris in order to learn about real life. He hopes to become an author, a writer of the history of aesthetics. In the beginning he is a mere 18-year-old social rube who is hopelessly clueless. He happens to meet an older wealthy entrepreneur on the ship back from Paris after seeing his uncle about an inheritance, and through this wealthy man meets and—hilariously instantaneously, without a word spoken, which was normal in the 1800s—“falls in love” with the wealthy man’s wife.

Thus begins the tale of Frédéric in Paris, the classic story of a young outsider, entering slowly into the very heart, the core of the Society of a major metropolitan city. He moves from woman to woman, always with the wealthy man’s wife—"Madame Arnoux”—at the forefront of his mind. Along the way there are perhaps half a dozen sexual/romantic intrigues. For something like 220 or 240 pages—the book is complete at 420 pages; the novel, at least the version I have, is the version published originally in 1964 and translated by Robert Baldick—Flaubert expertly plays out the sexual tension: There are glances and finger brushing and nods and reproaches and potential flirting but never a kiss, nor certainly anything more. He drags the tension between Frédéric and Madame Arnoux out excruciatingly…and of course we can’t stop reading as a result.

That is one of the strongest tools in the writer’s box: Sexual tension, spread out and dropped in slowly and with nuanced, titillating patience. This is probably three-quarters of the reason most movies work. We get hooked in because sex is one of the most fundamental desires of mankind. We have to know how it’ll all turn out.

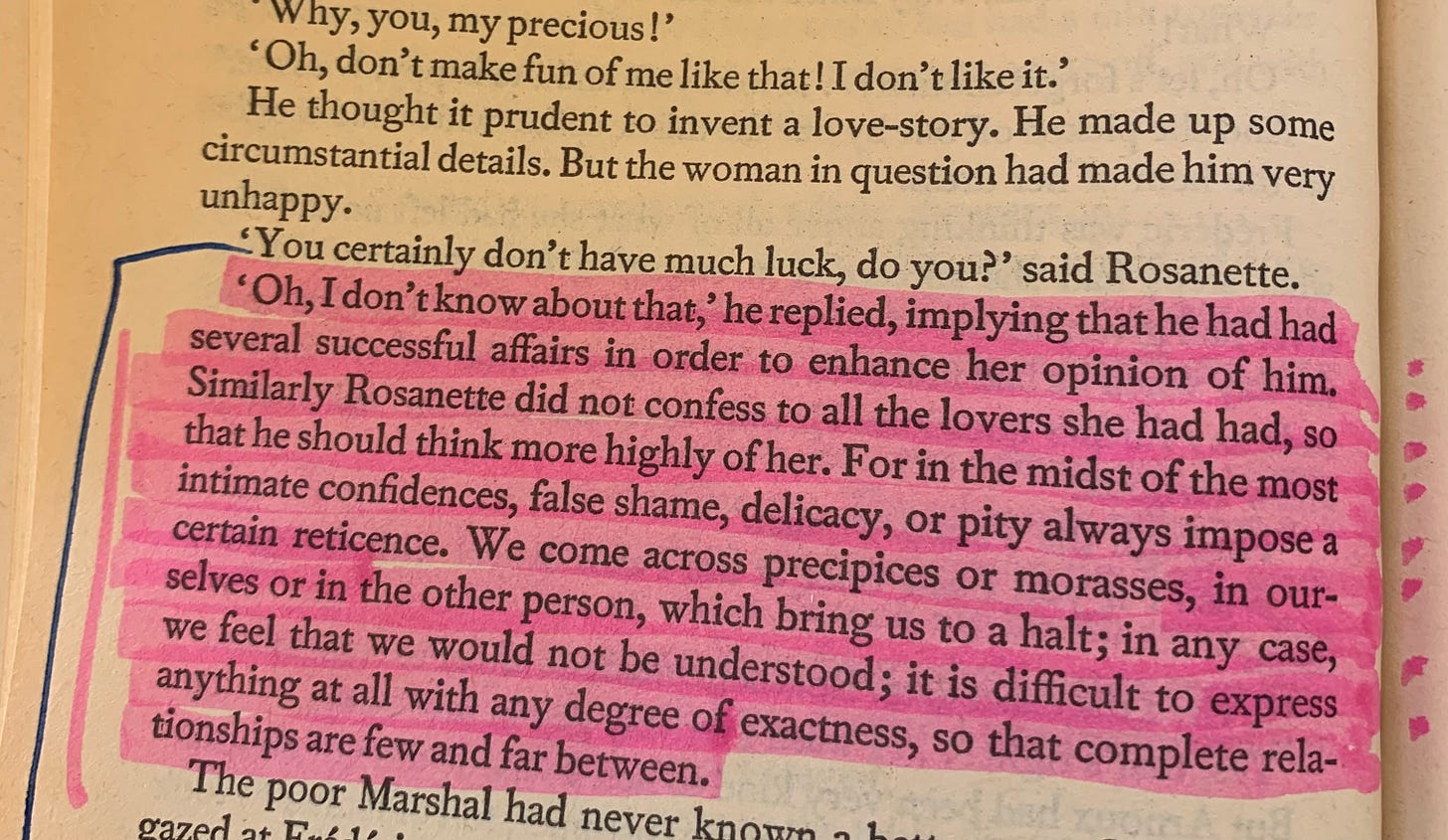

The novel is of the Naturalism, or realism school: Flaubert was not imagining so much as putting down a mix of his own autobiographical experience, the historical realities of the 1848 Paris Revolution—which is the backdrop of the novel—and an exploration of Paris in the 1840s. The title—Sentimental Education—itself points to an attempt to paint the portrait of a time and place, to explore the depths of how people felt, what they thought, what their expressed morals and values were, the dissonance between what they said in Society and what they actually did in “real life” (on the page).

That word—dissonance—says it all. Flaubert is also a master at this technique: The tension between what characters think say and do. Frédéric, of course, especially, given that he’s our main POV and our protagonist/hero, though he’s really more of an anti-hero. (The novel is technically told in 3rd-person POV, though we mostly, say 85%, stay within Frédéric’s head.) Frédéric tells countless women he loves them, and sometimes even believes it, only to turn around and chase after another woman, often a married one. Mistresses, courtesans (what we would now call “sex workers”), cheating married women, all of these abound in the novel.

Frédéric—somewhat hiding his own grotesque motives even from himself—genuinely seeks M. Arnoux’s (the wealthy man, who turns out, in the beginning, to be an art collector/dealer) friendship, even helping him later with financial assistance (when Frédéric comes into money), yet simultaneously he wants nothing more than to sleep with and ultimately marry Arnoux’s wife. The concepts of denial and self-rationalization are ripe in this novel. Ultimately, Frédéric, like most young men, then or now, wants what he wants. He isn’t a total narcissist or sociopath; he feels deep shame, fear, sadness, regret, even self-hatred. But he simply cannot help himself.

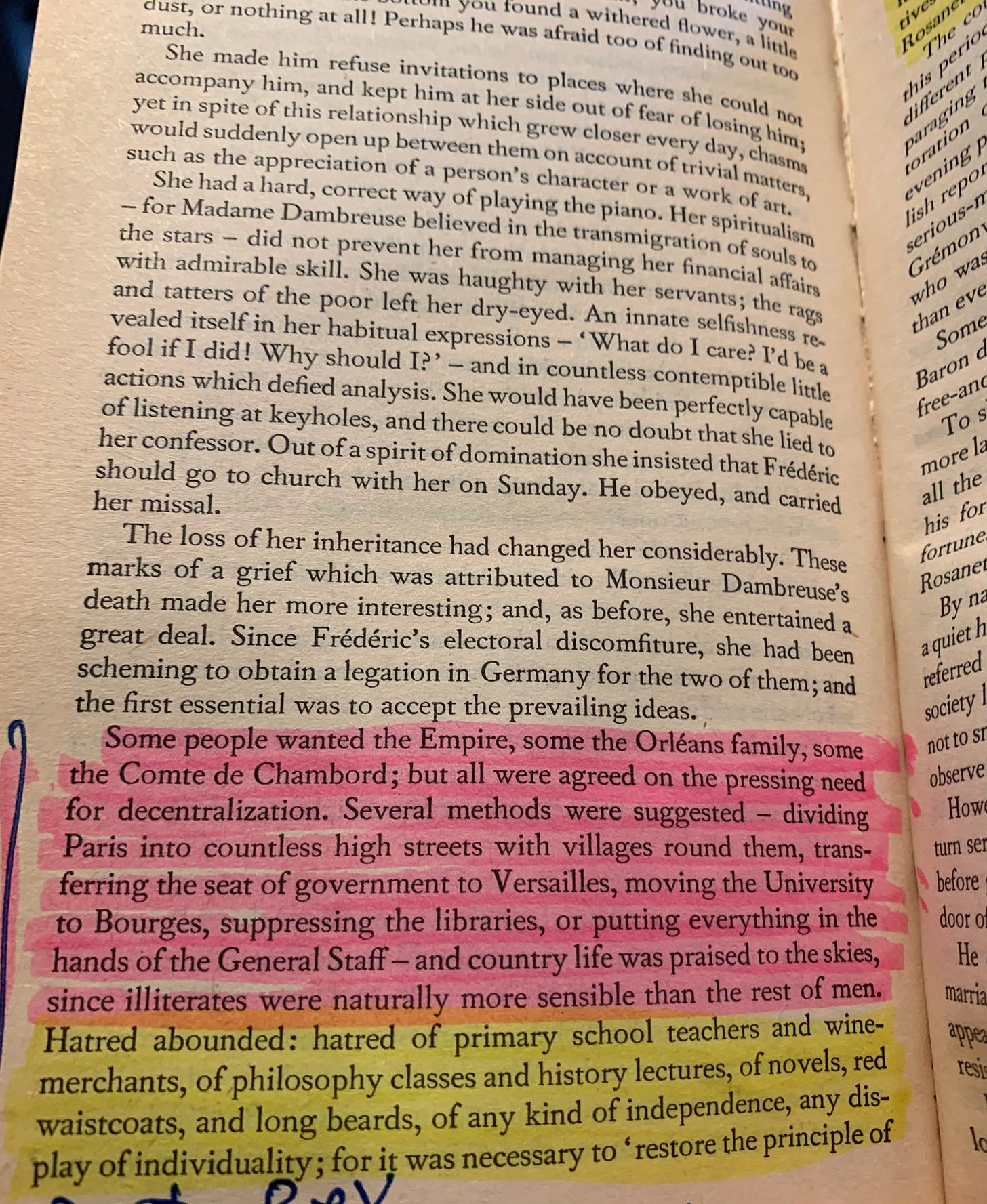

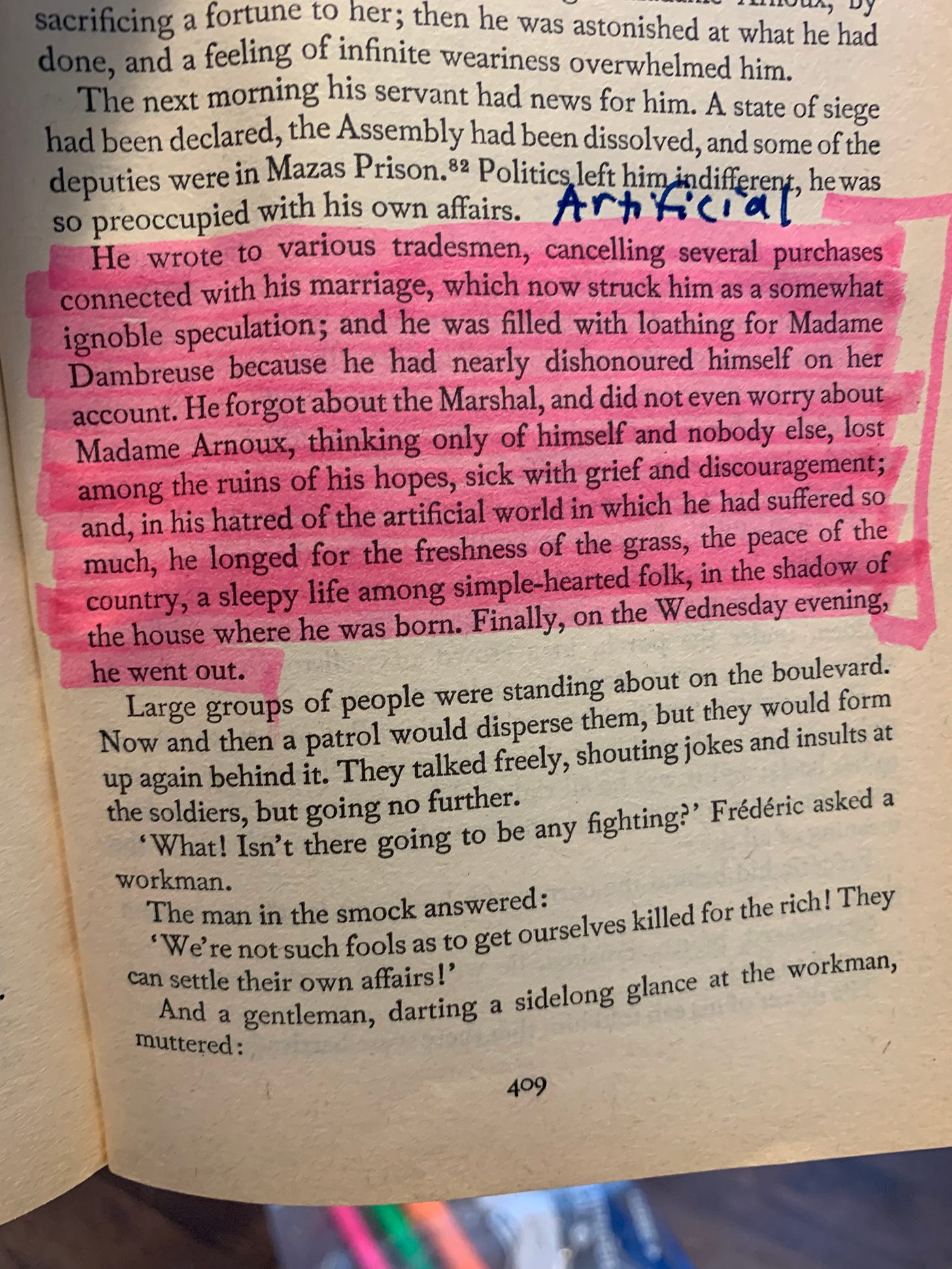

In the end, becoming wealthy first from his uncle’s inheritance (his uncle dies) and then from the Stock Exchange and other means, he navigates through the thick and complicated world of the Paris aristocracy of the 1840s. He becomes “of Society.” Mostly he finds it a boring, artificial social bubble which is both obnoxious, inane and unsustainable. Our hero is forced to see himself when the Revolution exposes the nasty hypocrisy of both the political Right and Left, the monarchy and the aristocracy and the Socialists and, even, the working-class masses. The whole situation throws a light on the mad absurdity of it all, on mankind in general.

The Revolution plays as a symbolic, metaphorical backdrop to the insipient chaos of his own wild, off-the-rails life. He’s throwing money every which way, loaning and giving it away like paper. His “friends” have all, by the end, more or less screwed him in various ways, and in many respects he, too, has screwed them. When he is rejected by Madame Arnoux for the final time, he turns to his on/off mistress.

When he then pursues and captures a very wealthy woman named Madame Dambreuse, whose husband is a banker and has been helping Frédéric, he thinks he’s going to be wealthy beyond imagination when Madame Dambreuse’s husband suddenly dies. But when Madame Dambreuse discovers that Frédéric’s on/off mistress is pregnant with his child, she leaves him. When his on/off mistress has their baby boy but then the baby dies, Frédéric is disgusted and leaves her. At the same time Madame Dambreuse knows out his incessant love for Madame Arnoux. Madame Arnoux, for her part, flees with her husband away from Paris to avoid paying massive debts owed.

Finally, hoping to marry a young woman from his rural hometown outside Paris who he once bounced on his knee when she was a little girl—a woman who loves him greatly and unconditionally, and who he’d earlier agreed to marry—he arrives in his hometown only to find his backstabbing best friend about to marry the young woman.

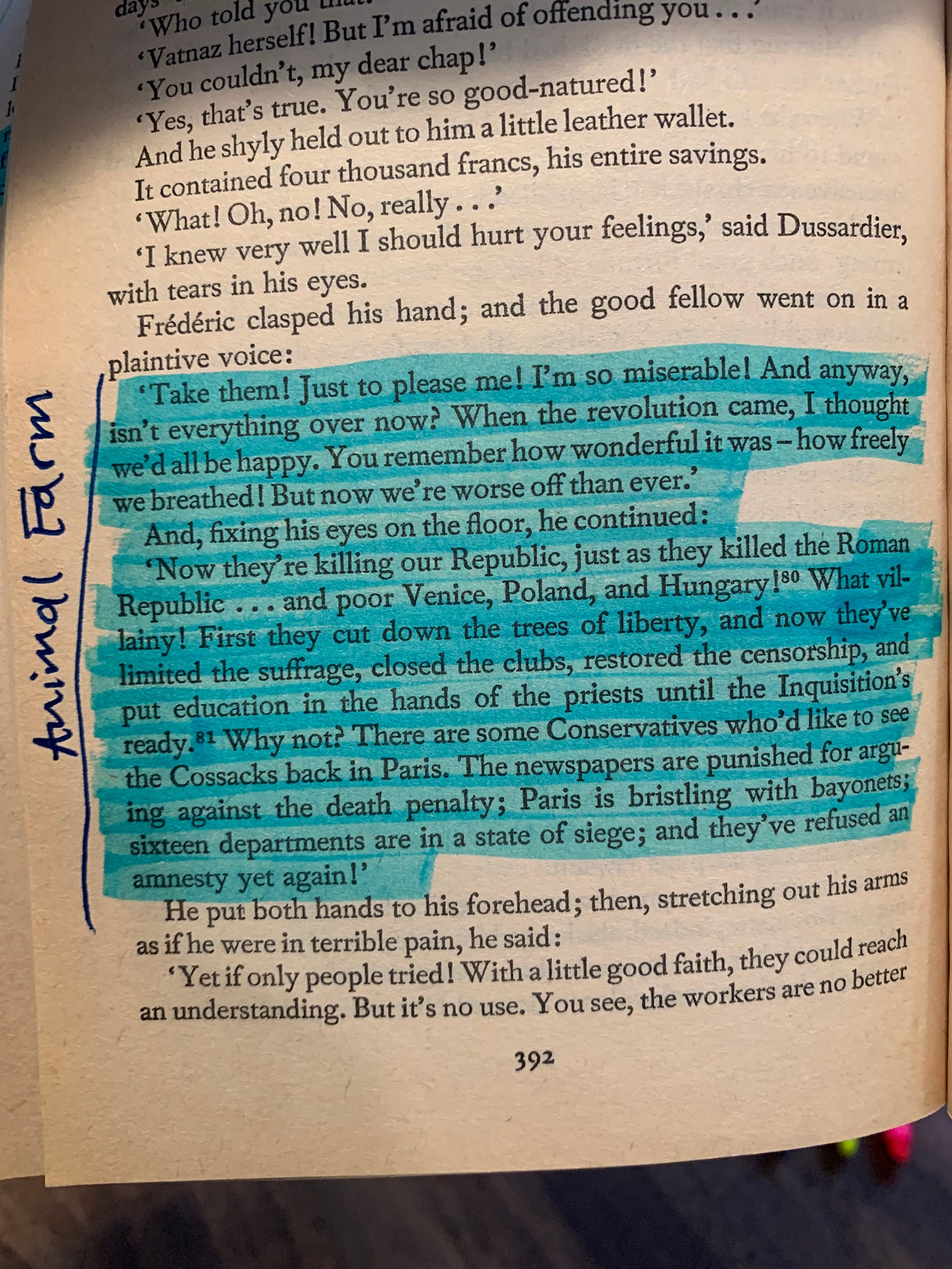

And so, in the end he remains alone, disillusioned, disheartened, a crust around his no-longer-naïve, no-longer-loving, no-longer-trusting heart. All has, basically, gone to shit. The 1848 Revolution in Paris only created a sort of sad Orwellian Animal Farm situation, reminiscent of our political moment right now in 2023: The Socialists, once praised by the working masses, have now become the neo-Fascists. They took down the aristocracy and the Monarchy only to encounter a newer, more hidden and complex tyranny.

There is a clear story and character ARC inherent in the novel: Frédéric goes from young innocent man greedy for life experience, love and freedom, to bitter, older scion of wisdom grasping that if there is one axiomatic truth in this life, it is this: We often do not get what we want, or what we hoped for, and, furthermore, chasing pleasures endlessly leads only to emotional and psychological ruin.

This is, again, mimicked by the 1848 Revolution. The lie is that if the Left gains power, they’ll be so much “better,” so much more humane and good and “pure” than their Conservative aristocratic, Monarchical predecessors. The Left/Right, Good/Bad binary is and always has been a lie, a toxic illusion that only feeds individual and tribal group power.

The truth—whether in politics or personal life—is always somewhere between these two extreme fringe poles.

What’s so perfect and lovely about Frédéric is that he is detailed and specific and therefore, ironically, completely universal. He is US, in other words. He shows us who we really are. Flaubert was always most interested in showing things “as they are,” not as we often want them to be. Frédéric is a total nuanced mixed bag of contradictions, complexities, desires, fears, ambitions, etc. He does many people a lot of solid good: He loans friends money constantly; he helps people get connected to the right people and get jobs; he exhibits bravery during the Revolution, leaving his on/off mistress at one point to go see and care for his best friend who’d been seriously injured during intense street fighting; he comes to many a friend’s aid when and how he can.

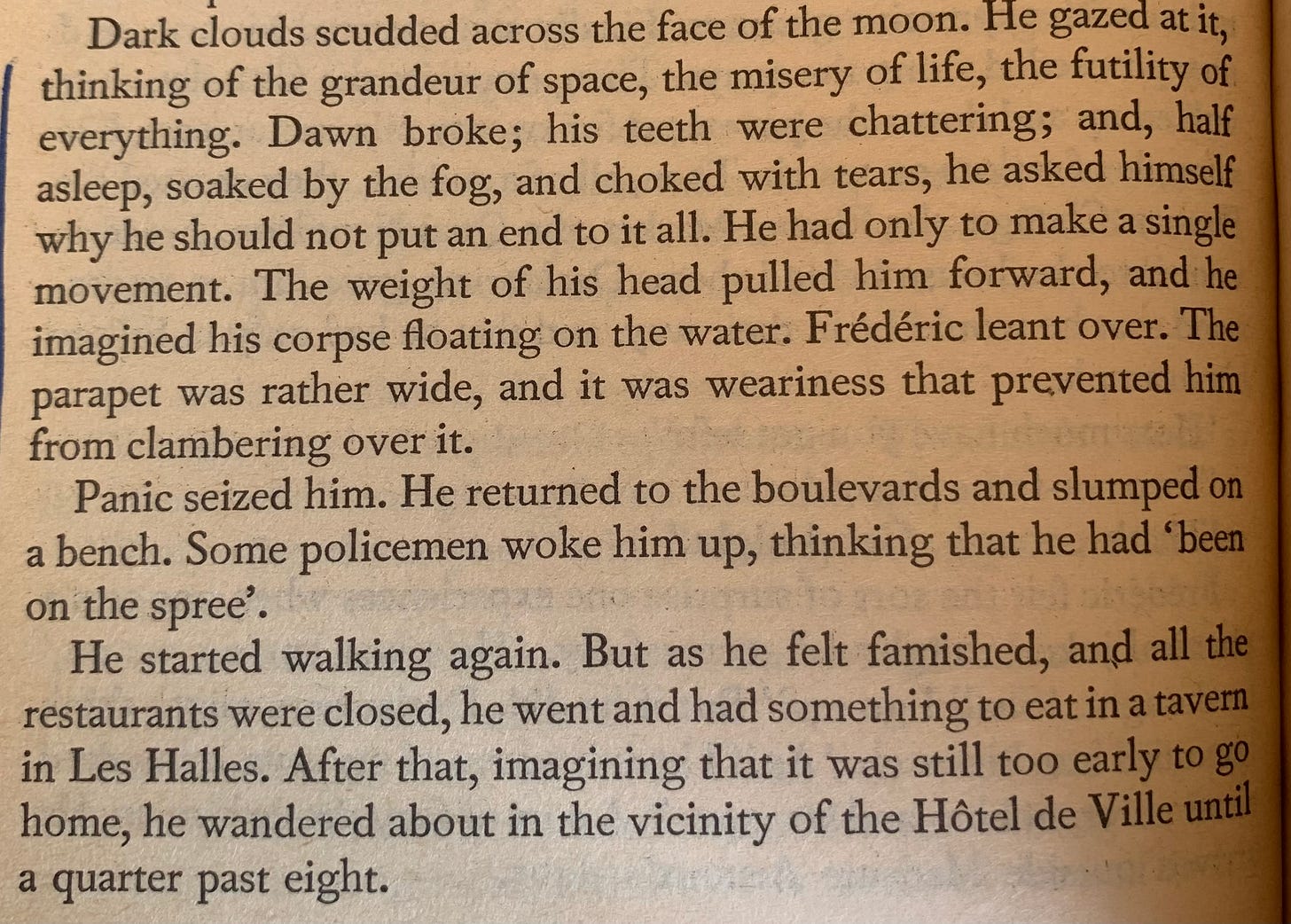

And yet: he pursues, desperately, married women. His motives are often disgustingly selfish. He’s a hypocrite, talking out of two sides of his mouth at the same time. He wants to write books and love a good woman and be happy, but he never writes his books, he never seems satisfied with just one woman, and he’s perpetually unhappy. He laments his long lost youth, when he still had innocent dreams of the long, distant future. He was given infinite chances to figure himself and “things” out and yet he face-planted every step of the way, in the end choosing his own egocentric desires over other human beings.

It's fitting that in the last pages of the book he speaks after a period of years with his old best friend, the one who married the young woman he’d wanted for himself after he destroyed all his other options. The two men—now older, wise, seasoned—remember being young, in their early teens, and going for the first time to a whore-house. “That was the happiest time we ever had,” they both agree.

In other words: Disillusionment. Frédéric had started out on his Paris experience as a young wayward youth in search of love, life experience, fun. He had the whole world before him, everything was open to his wants and wishes. But in the end, what he discovered was that “it”—Society, the aristocracy, women, men, capitalism, revolution, love—was more or less all a bunch of bullshit. He walked into the room of his new life open to all that he might find. He walked out of it thinking it had all been pointless. Artificial. Fake. Thin as paper. A joke. A lie. Totally, dumbly false. It all meant nothing, stood for nothing.

Life was like a whore-house, like a cheap prostitute; it drew you to it, sexually, with promise and lust and need. But in the end it was just an old woman with too much makeup, bored and broken, slipping her pale little hand into your pocket after sex to snatch your money, because she only fucked you to get paid.

That, for Flaubert, was the “society” of Paris. Life was like a painting on a wall: Not the real thing itself but a portrait of it. It was like the notion of eating dollar bills, thinking the cash itself could somehow provide sustenance. The truth, our hero learned the hard way, is that life—people—will always let you down. Perhaps the problem stems with the world at large, or with people, or, more realistically and maturely: Perhaps the problem lies with our own sordid expectations.

And that was the real issue at the core of the novel: Our own silly, perverse expectations.

Frédéric expected—childishly and unfairly—that he could somehow magically get everything he wanted, all the women, the money, the social prestige and status, the love, the regard, the personal and even political power (later in the novel he absurdly runs for elected political office). His head is summarily smashed against the wall of cold, hard reality when he realizes that he is lost; he doesn’t know who he is or what the hell he’s doing; and that fairness has little to do with the thing we call Real Life.

Nothing he wanted worked out the way he’d hoped it would. In some cases this led him, once he accepted it, to better and greater things. In other cases it nearly ruined him. He couldn’t roll with the punches—at least not in the beginning—because he felt that the punches weren’t fair, and that they should strike other people and in different ways. But this isn’t the way things work.

We don’t so much live a life as life happens to us. That isn’t at all to claim that we lack Free Will, or that we live in a deterministic or fatalistic world. This isn’t to claim that criminals should be forgiven for their crimes because they’re a “product of their environment.” Everyone has personal agency, the ultimate element of choice in life. And thank God we do. Otherwise we’d live in a world of automatons who simply did as they felt and had no consequences. (Imagine the horror this might lead to.)

But what I mean is: Try as we might, often (not always, but often) we find our course being directed not by ourselves but by circumstances around us. Our environment, yes. You fall in love and you see the future clearly and everything is glorious…and then a father suddenly dies. You’re excited about a relationship and then she leaves you out of the blue. You plan to travel and then your flight gets cancelled due to bad weather or political unrest. You plan on a big inheritance and then your guarantor gives all the money to charity, or changes the will, or something happens to disrupt the reality you expect. A million things in a million ways. Even just our day to day experience: You plan to exercise and then you and your partner instead get into a fight. You need good sleep before a long day but then your animals keep you awake or you suffer from insomnia.

Etc.

My point: We make plans and God laughs. Life happens as it does. We get to choose how we react or respond to these occurrences, these disruptions, and this shows us to ourselves; this provides us with a measure of our own integrity, character, personality.

This was the gift, presented in the form of gorgeous literature, that Flaubert gave us. He shows us our love, our gratitude, our depth, are glory, our pride, our ego, our petulance, our deceit, our self-lies, our immorality, our contradictions and hypocrisy, our troubled, complex truths. He gives us a sort of scientific fictive analysis of The Human Condition.

We are better human beings for it.

Will do

We are better human beings for it. Absolutely