Sometime in early 2022, my mother’s 92-year-old still-working-as-a-therapist colleague at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art decided to give away most of her book collection.

She was moving, it turned out. She knew, through my mother, that her late thirties son was a writer and loved reading. Therefore, she told my mom to let me come over some day and take what I wanted.

My mom’s friend lived near San Roque, in Santa Barbara, where my mom lives. The woman’s house was up in the hills near Inspiration Point, where I’d hiked dozens of times in 2021. It was beautiful back there. She had a view to die for, of the whole of sprawling S.B. A sort of paradise.

She and I chatted briefly and then she led me into the library room. There were hundreds of books. I felt a thrill like an alcoholic who steps into a bar for the first time after a week of not drinking. An electric tingle raced down my spine. My heart thudded in my chest.

There were mostly classics: Hemingway; Faulkner; Fitzgerald; O’Connor; etc. But also other books, such as Albert Camus, James Baldwin, Salman Rushdie, and, of course, a length of shelf dedicated exclusively to Haruki Murakami.

She had Norwegian Wood, Kafka on the Shore, Sputnik Sweetheart, Hear the Wind Sing, First Person Singular (stories) and, among many others, Dance Dance Dance.

I’d always appreciated the Japanese author (born 1949). As an alcoholic burgeoning writer in my early and mid-twenties, one of my closest [wannabe] writer friends had been obsessed with the author. (Ditto with Elliott Smith; as a result I was turned off on both for many years.) I’d only read The Windup Bird Chronicle and What we Talk About When We Talk about Running.

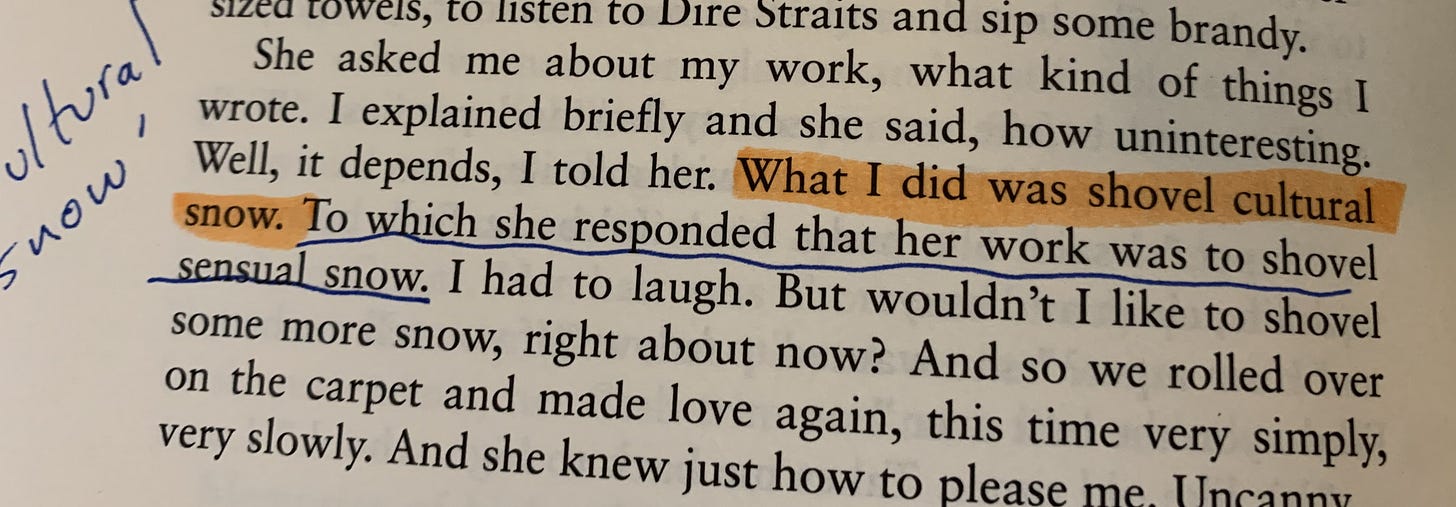

I knew he was a Japanese author obsessed with American culture, that he’d been hugely inspired by Hemingway, and that his style had been born by writing in Japanese and then “translating” that into English, which he had a limited knowledge of and ability with. In translating into English, he was forced to use basic, simple language which created a strong, unique voice. He wanted to cut out the literary pretentions and big words. His goal—as any serious artist—was communication, not flowery purple prose.

*

I carried out several loads of books that morning and dumped them haphazardly into my car. Perhaps I took 50 books. I was beyond excited. I had taken all the Murakami.

For months I didn’t pick a single Murakami book up. I continued to read voraciously, but I just wasn’t ready yet. Finally—for who knows what reason—I snagged Dance Dance Dance one day and read it in a week.

Like The Windup Bird Chronicle—and I assume most of his novels—there is a “plot” but the plot is very much beside the point. Murakami isn’t interested in conventional, traditional mechanics of plot; he’s interested in characters, tension, and plot-threads which sometimes go places and sometimes go nowhere. It makes me think of the Goosebump books of the 90s, choose your own adventure.

Murakami is a master of sexual tension. (I wrote about sexual tension here.) He is the contemporary author to study if you’re a new writer and you want to learn how to string a reader along and need to know how a relationship will end. He is genius at hooking our interest, then slowing things down (thus ironically speeding things up because we’re interested and want to know how it’ll all end) and cutting things off, forcing you to the next thing.

He loves raising questions in his novels, both implicitly and explicitly. You then have to keep reading to get the answers. The answers are almost never what you expect. He keeps you guessing, on your cognitive toes. He will open up half a dozen threads—separate little plot-threads—as if an iPhone with six different tabs open, swinging back and forth between tab A and tab F.

His prose is subtle, clear, direct, and yet also full of metaphor, symbolism and depth. Not always. Some sections are pure entertainment. Sexual tension. He loves dialogue and thrives on it. He writes some of the most realistic dialogue I’ve read. Sometimes parts of his novels can feel like a screenplay. He’s not afraid to go for pages and pages with solely dialogue, and he’s also not afraid of using both short spats of dialogue lines and also large, sometimes page-long chunks of monologue.

There’s always an intriguing admixture of realism and the supernatural in his novels, too. Things are real on the surface, but just underneath things aren’t exactly as they seem…things are often just a few degrees off center. Things are never just what they appear to be. In this way Murakami captures what it genuinely feels like to be alive in a human meat suit with a living, blood-pumping brain. He creates a sort of illusory-literary hall of mirrors.

The “plot” of Dance Dance Dance is as follows. The first-person narrator is obsessed with a certain hotel he once stayed at with his ex. His ex has disappeared. (This is in Japan.) He is a freelance writer. He saves up and quits work for a while. He is bored, lonely and sad. Confused. He goes to the hotel. He meets a pretty woman who works behind the counter. They slowly develop a friendship full of potential and sexual tension. He experiences The Sheep Man, a fantastical man who tells him to dance in the darkness of a certain floor of the hotel.

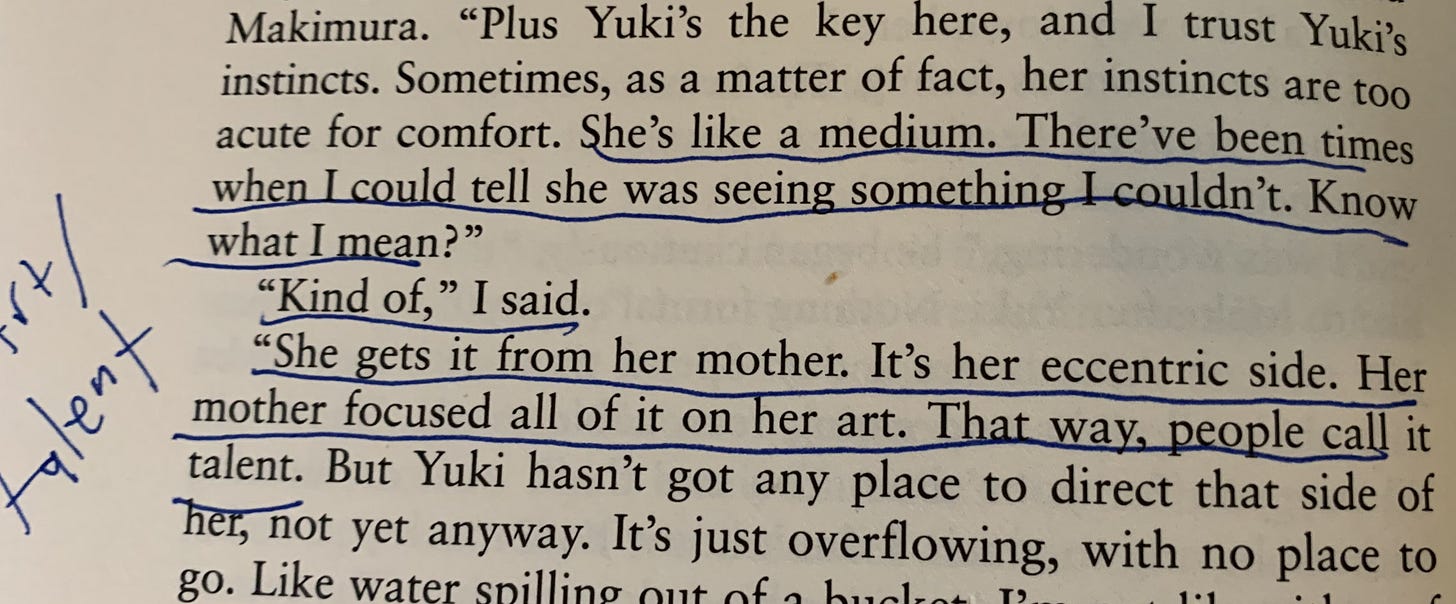

When he decides to leave the hotel, he is asked by his receptionist friend to take a 13-year-old girl back to Tokyo with him. He’d seen the girl before. Why take her? Her mother is a famous artist and cognitive space-cadet who took off to Kathmandu and forgot about her daughter. She needs to get back safely to Tokyo. He agrees to escort her safely home.

Speaking of sex: Murakami also does not shy away from taboo. Enter the Japanese Lolita, people. Nothing ever happens, physically, between the narrator (who is a 34-year-old man) and the 13-year-old girl…but there is abundant sexual tension. And they tap-dance around sexual issues throughout the book. Granted, this was a Japanese author writing in the 1980s; different culture and time.

Meanwhile the narrator has reconnected with an old friend from high school. The friend is a famous actor now. They start hanging out regularly. The narrator still senses some bigger connection between his actor friend, the girl, his ex, the receptionist and the hotel. But it’s all a mystery. One night he and his actor friend go to the friend’s apartment, get drunk and order expensive call girls. They have sex with the girls. The next day the girl the narrator slept with is found murdered. The narrator is hauled in by homicide investigators and questioned, brutally, for three days, spending the night in the unlocked jail. It reads like Kafka’s The Trial, and I think this is on purpose. Bureaucracy. He does not mention his actor friend to the police.

There’s more, of course. He gets more involved with the 13-year-old girl, is paid to care for her by the girl’s dysfunctional father, goes to Hawaii for a while, sleeps with the receptionist at the hotel, and finally solves the murder mystery. (I won’t tell you the end, in case you read the book.)

Murakami loves to keep readers guessing. And you’re frequently wrong. His language is full of American music references, American novels, American culture. He mentions name-brands and loves illustrating people, places and things using the most minute details. His prose is rich and so full of clarity that it almost feels embarrassing. But that really is the true goal of art: Righteous clarity.

To enter a Murakami novel is to enter not just a story but an experience, or, further, a dreamscape. Randomness is injected gently into the picture. We wonder: Where are we going? We wonder: Is this scene real or a dream? Is this “actually happening?”

The author plays with realism and space/time, bending it, warping it like in the 2014 film Interstellar. He creates literary black-holes, wormholes, etc. We circle around the planets he creates. There is truly no other writer like Murakami. He writes so profoundly because he obviously trusts his own inner power. He doesn’t try to “sound” like a writer; he just writes. There’s a massive difference.

In short, Murakami is a strange mix of Kafka, Bukowski and Hemingway, with the addition of his own totally original style and voice to boot.

His work succeeds simply because he possesses the guts to put things down as he grasps them, in their most surreal, authentic state.