2. The following is not a full book review; expect that later

~

The word “seminal” is described by Mirriam-Webster as both “of, relating to, or consisting of seed or semen,” and also as “containing or contributing the seeds of later development (creative, original).” The words stems originally from the Latin “seminalis” meaning “semen seed.” In other words: Birth; growth; change.

Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga, was a seminal 1967 classic by Hunter S. Thompson, the father of Gonzo Journalism. (“The Rum Diary” was in draft form and written prior but worked on for years and not published until much later.) It was HST’s first book. It’s ironic in a beautiful way that, concurrent with the so-called hippie Summer of Love—my parents’ generation—out came the literary demon-semen of the wild, raucous ride that was the sordid tale of the California Hell’s Angels.

I can’t recall when exactly I first read Hell’s Angels, but my memory tells me it was long, long ago, somewhere around age 23. Vaguely, I can picture myself reading an old hardback version in the musty Mesa Community College library, the school I attended for a while back in those days—circa 2005, 2006—when I lived in San Diego. When I recall that first read I seem to recollect a sense of manic boredom and also diabolical interest, all intermingled.

The story felt too expository to me back, then; it took too long to explain the who what when where and why. The strange tale was too steeped in historical context and backstory. Thompson was fundamentally a journalist and it was of course a journalistic book. (With his telltale Gonzo form of inserting himself belligerently into the piece.) For me, back then, immature and always wanting action—both in books and in real life—I recall feeling half-bored. I couldn’t fully wrap my naïve head around the terrible truths he was trying to disseminate about a ragged gang of two-wheeled rebel hounds whose only major goal was to break the rules. (Even as I was doing the same thing in my own, more semi-bourgeoise punk-rock-burgeoning-writer manner.)

Now, of course, at age 41, it’s a very different story. I’m only about 100 pages deep—over 1/3rd of the way through—and I find it, overall, riveting. I can see, however, why I got bored at 23. HST in this book has a way of overexplaining, of going into the microscopic, granular details about, say, the industrial-financial history of motorcycles in general and Harley Davidsons in particular. It reminds one of Melville going on for 100 pages in “Moby Dick” about the different sizes, species and physical traits of various whales. Some of HST’s descriptions, I felt, might have benefitted from cutting. Perhaps I’m wrong.

And yet there’s no denying Thompson’s genius, and from multiple angles. First, his writing style.

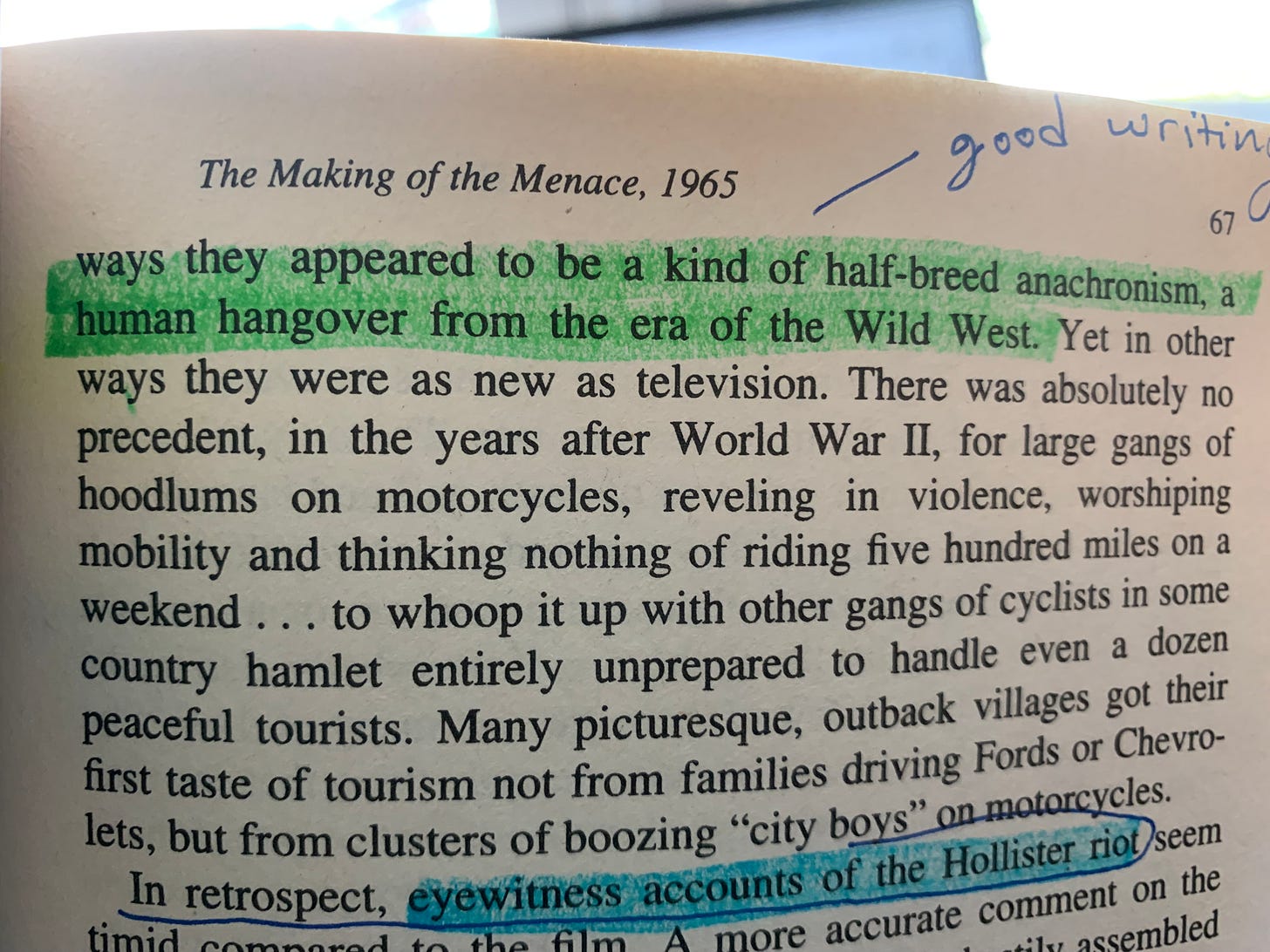

Here’s a fantastic example (page 66/67 of the Ballantine paperback version of the book, copyright renewed 1994):

“The concept of the ‘motorcycle outlaw’ was as uniquely American as jazz. Nothing like them had ever existed. In some ways they appeared to be a kind of half-breed anachronism, a human hangover from the era of the Wild West.”

A “human hangover”: I love that phrase. It’s drenched in nostalgia for a forgotten time in America’s history (westward expansion, cowboys) and simultaneously works perfectly with the feel, vibe and energy of the 20th century Hell’s Angels, perhaps equivalent in a way to 19th century cowboys moving west across America, battling Indians and fighting for their idea of “Manifest Destiny.” (I’m not supporting the notion of Manifest Destiny, only claiming it brings back a time and mood.) “Human hangover” also gives us the image of humanity being spiritually “hungover,” which is delicious. You can envision the rugged iron-hog-riding madmen, much like cowboys in the 1840s, plowing not across the land on horses but across the highways of 20th century America.

The quote above is also brilliant because it showcases Thompson’s brutal, authoritative literary voice. He spent a year with the iron-horse pseudo-gangsters, the kings of the American Road, and you can tell. You feel it in his confident, ballsy voice and tone. HST pulls no punches: He tells you exactly what the Angels are, what they aren’t, how they see and think of themselves, how society thinks about and sees them (at the time of the writing, 1965/66), and the uncomfortable cohesion (or lack thereof), the awkward tango between Angels and The Normies, or between Angels and cops (not as different, in some ways, as you might imagine).

Thompson knows his stuff. Being HST—and it being the mid-1960s, when journalism was actually journalism and not ideological-theatre-pig-slop—the book reads not like indoctrination, obvious bias, or an ideological tract designed to tell you how to think, but instead as a serious deep-dive into the awful, fascinating world of semi-low-life counter-culture men who ride “chopped hogs,” fight everyone who they feel offended by for any reason, tear down whole towns for fun, and rape, pillage and wreck whatever might be stupid enough to get in their way. They are voluntary outsiders, rejecting the conventional 9-5 status quo. Men who insist on doing things their own way on their own terms.

In my YA punk novel—The Crew—HST is read and discussed. He was, let’s face it, similar to someone like Johnny Cash, one of the first true “punks.” (The Man in Black.) Thompson (1937-2005) came of age before the rise of mid-70s punk rock (Ramones, Sex Pistols, and their predecessors like Iggy Pop in the late 60s), but his spirit was wholly and totally punk rock. Picture HST with a tall green mohawk, the sides of his head shaved (before he went bald) and a cigarette in a holder dangling from his lips; it wouldn’t be a stretch. His literary cousin—the non-journalistic fiction writer version of himself—surely must be Henry Miller. Who else? (Another anarchist punker before punk.)

What’s refreshing about Hell’s Angels—and any book by Thompson and the majority of books from most of the 20th century—is that I don’t feel lied to. I also don’t feel condescended to, or told what or how to think. HST just puts it all down, based on his experience, and he does it honestly, borderline recklessly. (As some might say in today’s parlance he gives “zero fucks.”) He was actually, genuinely interested in getting as close to the bone of that weird thing we’ve all lost sight of today called Truth. Yes, all human beings have *some* bias…but we can do our best to either openly admit our biases up front…and/or slice down the level or amount of our bias by attempting to be as objective as we can, knowing we’ll never get to 0%.

There’s something incredibly original, awe-inspiring, and authentic about a writer telling it like it is, with upfront bias and dazzled ego included, laying down the necessary context and backstory for readers to grasp the true picture of the Hell’s Angels in mid-1960s America. HST tells the tale of how the Angels, at that time, became famous through first the alleged Monterrey Rape (which became very confused), and then the tearing down of a town and an ensuing riot.

The media became fascinated by these rugged two-wheeled heathens with their bandannas and long hair and thick beards and chopped hogs with the tall chrome handlebars. Hell’s Angels T-shirts were made and distributed. Interviews with Angels were produced. One Angel was even on the cover of a major magazine. Terrible stories were dredged up. They had a bad, repulsive reputation. They liked to brawl. A bar or a gas-station could be torn down in minutes.

HST originally did a piece on the Angels for The Nation. This became the groundwork for a longer piece, which became this book. He got his own hog. He rode with and spent many dozens of hours with these guys. He became entwined with their ilk. He was part of the club, to some degree, though of course never an actual Angel; he never earned “the colors.”

It makes me think of Jon Krakauer’s story for Outside Magazine which became the basis for the nonfiction book, Into the Wild (fantastic book and good movie). Sometimes journalists go out there and do good reporting and that becomes the mulch which a tree will ultimately grow from.

I find myself desiring an HST for the 21st century, for our times now. Someone with the brawn and the guts to tell the truth without picking sides, without veering off into conspiracy theory, with that totalizing voice and genuine attraction to capital-T Truth. Maybe there is someone like this and I’m just not aware of them. Perhaps to some degree a journalist such as The Free Press’s Bari Weiss makes the grade. Certainly she gets closer than, say, anyone I can think of at The New Yorker or the New York Times, given the level of bias, cancellation and speech/press editorial restriction we’ve seen the past five, seven years. (That does to some degree seem to be changing for the better, slowly.)

Thompson’s book is good precisely because his writing is top-notch, and because his topic is wildly fascinating (how could it not be?), and because he was allowed to follow his nose wherever it scented a solid story. Being able to allow readers to think for themselves and come up with their own conclusions—what an idea!—we as readers feel respected and treated like intelligent adults. And for that alone I am grateful.

For the rest of the book, and for the style, voice, structure and provocative, juicy sentences: I feel honored.

Expect a full book review on Hell’s Angels soon. This was just a taste.

I read this book decades ago and your take here brings it back to life. I should check it out again. I agree we need more of HST in this world, and less sanctimony and condescension from our writers. Less goody goody explanations in the text and careful word parsing. It is hard to avoid these days but I do believe it is necessary. Glad to see I'm not alone in seeing this.

Never got around to reading Hunter Thompson. Good to know he's not someone only meant for one's impressionable years.

As for a 21st century Hunter Thompson, that can never happen because a lot of what are called conspiracy theories are simply called that by the corrupt media to make sure "respectable" people have nothing to do with it. That media environment didn't exist in the 60s, although no doubt it had other problems of its own. A present-day Thompson will have to wade through that murk one way or another if the truth is their goal. The upside is that it doesn't really matter if it's a conspiracy theory. If a commitment to the truth and to telling things as they are is maintained, what other people call it won't matter. Of course I'm not talking about UFO's here. Although the way the media is now, a Thompsonesque book about UFO's might generate more seriousness than a lot of the other stuff out there.