Henry Valentine Miller is one of the great unsung heroes, one of the finest rejected writers of the 20th century. Rejected, that is, by the “insider” literary establishment. Why? Because his books—mostly penned and published starting in his 40s—were considered “obscene.” Even now, in 2023, I find some of the language shocking. His liberal use of the word cunt is, even now, pushy and aggressive and inappropriate.

But hasn’t that often been the point of great literature? To push past boundaries of propriety, piety and good manners? I think of classics like J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, which, unbelievably, we were forced to stop reading at my private college-prep high school in the year 2000 due to parents’ complaints. Or anything by, say, Frank Norris in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Or how about H.L. Mencken. Nietzsche. Faulkner. Even Dickens, in the way he portrayed brutal realism.

Literature was never a highly educated, sweetly sophisticated, upper-class phenomenon. It’s strangely become that today, mainly because only a tiny fraction of genuine, serious “writers” exist. Now it’s all about streaming and YouTube and social media and podcasts. How many people—especially under 30—even read anymore? And, of those that do, what are they reading? Ideology has so infected the publishing industry that we’re floating on the most Orwellian moment in books in American history. And then of course you’ve got legal book-banning by the Republicans, and cultural banning and cancellation from the fringe-Left. Miller, like Allen Ginsberg in the 1950s, was on the forefront of the legal/obscenity/free speech movement in books. His Tropic books were mostly banned in the States until 1961, having been published by a small press in France in the 1930s.

But if you’re the kind of quick-to-judge person who dismisses Miller simply because his prose can be “pornographic,” I think you’re missing out on a brilliant mind. Even the harshly critical, fiercely independent-minded George Orwell, in his essay collection, praises Miller. Ditto high praise from Norman Mailer. The thing is: The highly sexualized language is a thin veil protecting a rich, wildly imaginative mind. No writer can use myth, metaphor, simile and physical description to detail the inner landscape of a man like Henry Miller.

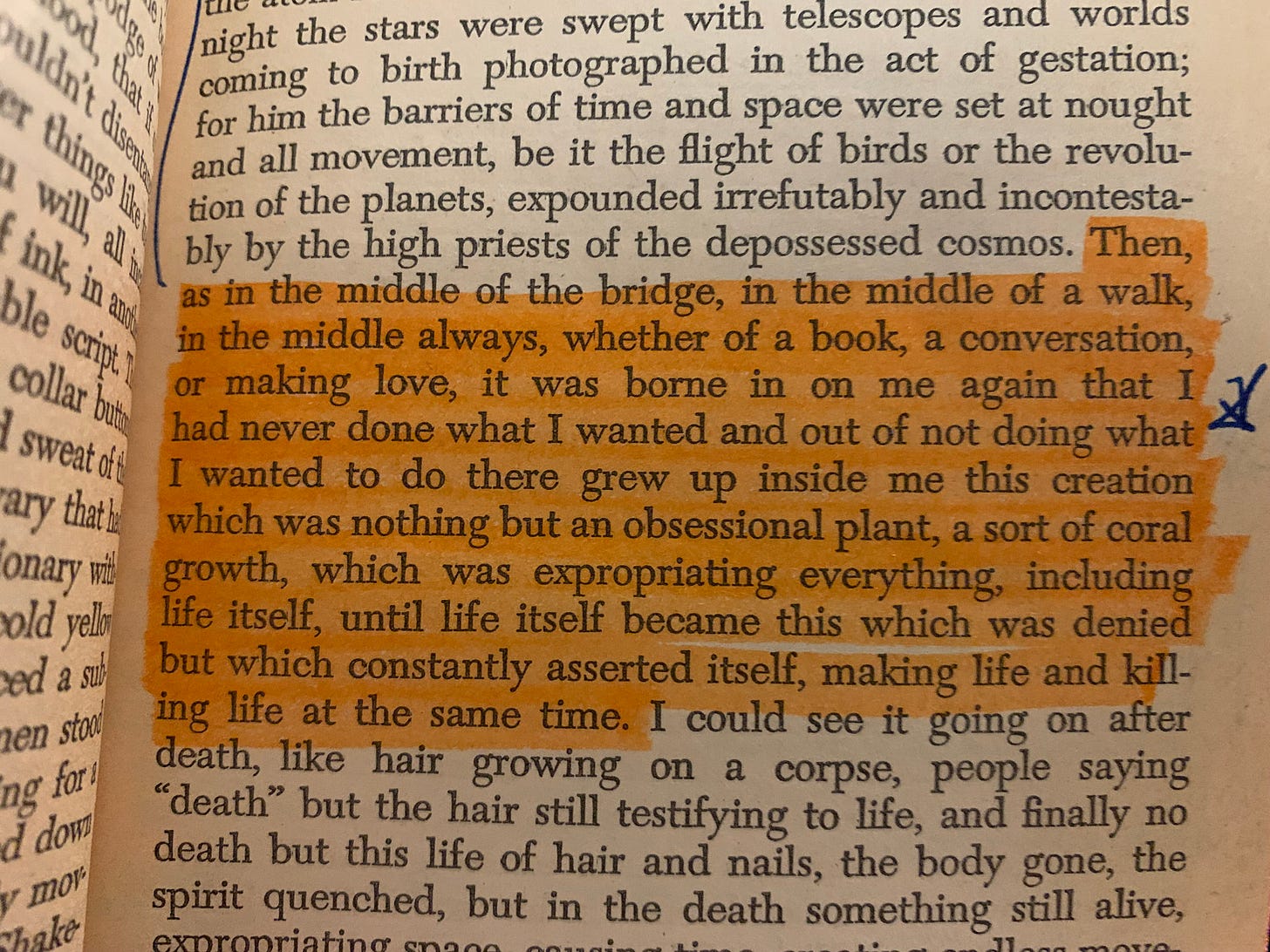

His ability to break down his complex, nuanced, intense thoughts is uncanny. His genuine desire to crack open both his brain and his heart and share it with the reader is unrivaled. Part poet, part angry belligerent child, part spiritual soldier, part lost soul, he ravages our senses, spikes our sympathy, arouses both our ire and our pity, and makes us want to hug him and sock him in the nose all magically at once.

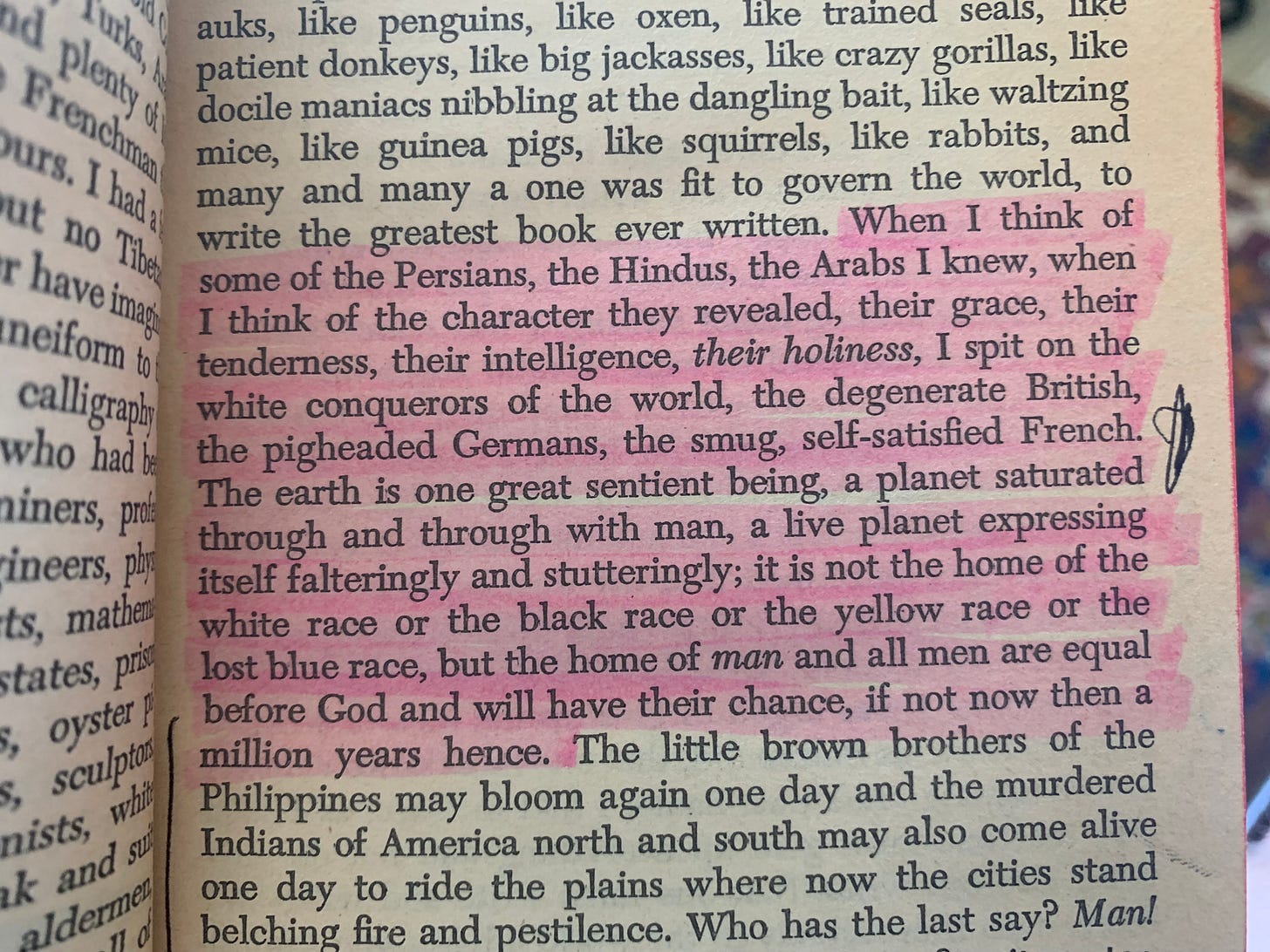

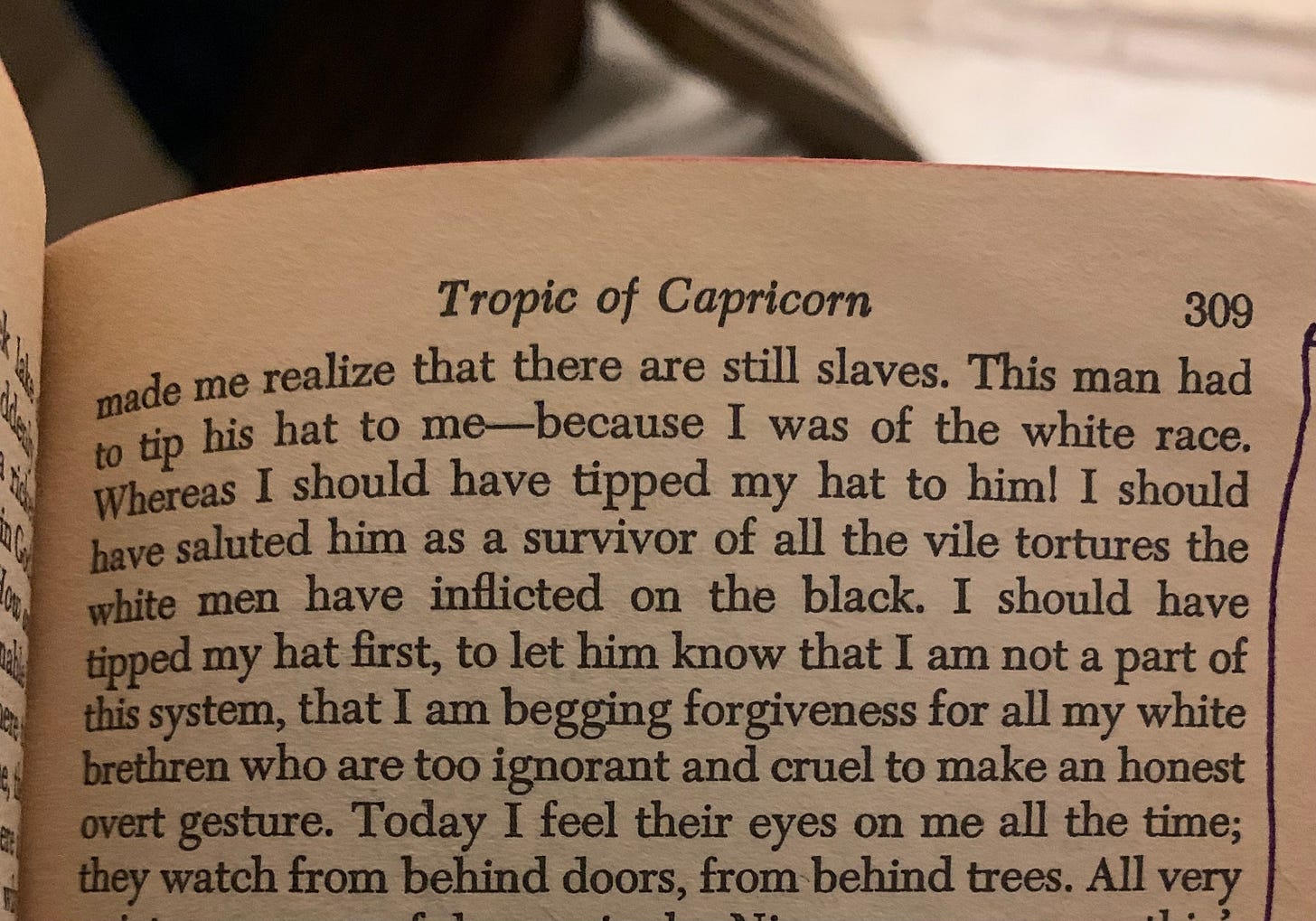

I won’t defend Henry Miller the man. Henry Miller the artist, yes. The seer, the visionary, the spiritual witness, yes. But not the physical man himself. He wasn’t good or admirable. You wouldn’t want your kid to turn out like him. He basically ditched his wife and child for his art. He slept with anything that had a pulse. He contemplated rape. He spent time with derelicts who are violent towards women. He thought mostly of himself, and constantly. He stole, borrowed money without returning it, and focused exclusively on his writing to the point of forgetting other people entirely. On the flip side he rejected the obsession with conventional identity, claiming both male and female traits, and he eschewed white racism against Black people. He mocked Jews and yet had many Jewish friends.

He was definitely a man of his time (born, amazingly, in 1891), and a native New Yorker, growing up in both Manhattan and Brooklyn. He did not come from a family with much money. He enjoyed wandering the streets, seeing the people, observing the urban anarchy unfolding around him. He couldn’t keep a job longer than a couple of months most of the time. He hopped from job to job to job, always dead-end projects. He was constantly in debt. He knew, from a fairly young age, that he had books within him, he just didn’t know how to get that out, how to create externally from what was bubbling, burning inside him, how to make the internal external. Until he left NYC for Paris in the late 1920s, in his late thirties by then. He got a late start creatively, at least when it came to externals.

Later, after the Paris years, he settled in Pacific Palisades and then Big Sur. He was a consummate artist in the style of Bob Dylan. Dylan kept creating and doing it his own way, ignoring the masses who wanted him to play the same folk songs for eternity. Dylan was an artist, not an activist, and the kids of the 1960s never grasped that. Ditto Miller, who in some ways became the first “Substack writer” in a certain sense. Not really. But theoretically. Determined after he really got started as a writer to not have to work normal, menial jobs like everyone else, he asked patrons for subscriptions, which back then, in the 1950s and 60s, meant money donations so he could continue his writing without distractions.

People loved Miller and helped him out in myriad ways. He developed a cult following. People let him live in apartments rent-free. Gave him houses. Paid for his living expenses. Gave him allowances. Paid subscriptions to help him along. Etc. He became a cult-classic, like Kerouac did in the 1950s as “king of the Beats” (a title Kerouac loathed and resented). People made their way to Big Sur to meet the determined artist. The man who refused to work. The so-called “anarchist” who believed in nothing. The man who had dedicated his entire life exclusively to his Art.

Like Bukowski, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Jack London, even David Foster Wallace, Miller in his own way was troubled. He had his demons. His sexual obsessions. His stubborn rebellious, “anti” contrarian nature. And his past with women. But none of those things made him a bad man. They only made him human. Flawed, weak, complex, unusual. It’s rare to encounter a human being who subordinates everything to their chosen Art. Miller was one who did do this, and he took the project as far as it could go. Growing up in NYC, living as an ex-pat in Paris, then coming to the vibrant California coast, he moved about the world like a man possessed.

The opening line of Tropic of Capricorn is: “Once you have given up the ghost, everything follows with dead certainty, even in the midst of chaos.”

This line seems to have summed up Miller’s long life (1891-1980). Once you let go of control, he seems to be suggesting, things crash into line, even while your life appears to be spinning out of control. Miller’s life in the 1910s and 1920s, in his turbulent twenties, was chock-full of anarchy. Drinking, girls, millions of bad jobs, debt, family dysfunction, writing books in his head, the unsureness of his open future. What does a burgeoning writer do in a normative, conventional, boring world which expects you to conform? Miller was fundamentally unable to conform to society’s droll expectations. He was a seer, a witness, a visionary, an artist ahead of his time by decades.

True, he had a Christ-complex. A sort of narcissism and megalomania out of proportion with reality. Yet for all his inner cognitive distortions he also was a man desperately trying to fit in, be accepted, ultimately to be understood. I don’t think he ever fully, truly was understood, but in the end he was most certainly read, respected and often worshipped. Bold pioneers are always looked up to with awe.

Like Hemingway, David Foster Wallace and other white male 20th century authors, Miller has been derided by some circles. Feminists, for one. Proper “civilized” contemporary culture, for another. But what do they know? There’s something decidedly universal about Miller’s prose and message. He cuts down to the very white grizzled bone of our human sense of ourselves. He’s so goddamned real. Raw. Authentic. There’s zero timidity in his writing. He knives right to the spiritual core of the human condition, the neediness, the expectations, the depression, the rage, the fear, the lostness.

We read Miller because he presents us to ourselves. Some try to decry and deny him for the same reason. Nowadays writing seems to be more about ideological “uplift” than the painful sore of realism. Writers, some say, are supposed to carry a socio-political message, they’re supposed to make readers feel safe, feel accepted, feel like part of “the community.” You wouldn’t want to offend anyone, or fat-shame, or “victim-blame,” would you?

The above is of course absurd and anti-Art. Writing—true literature—has never been about social kindness, safety, appropriateness. No, art is one area where we don’t want politics, where we don’t want safety, where we don’t want ideology. Instead we want freedom of speech. We want to be pushed into uncomfortable territory. We want to face our own ugly selves in the mirror, awkward and nasty as that may sometimes definitely be. We want truth. Not “the” truth but any given writer’s angle on the truth, on their truth. Truth, of course, is frequently ugly and deplorable. Human beings are often ugly and deplorable. Such is the nature of existence.

You don’t read Miller for fancy, sophisticated language. Read Nabokov for that. You don’t read Miller for an exciting plot. For that you have Dostoevsky. You don’t read Miller for safety or to confirm your own biases. You read Miller for the authentic, no-holds-barred literary voice. For the guts. For the realism. For the imagination. For the honesty and search for universal truth. For the spectrum of wild, chaotic emotion which spans the human field of experience. For the rich, vivid descriptions. For the setting. For the feeling of being pushed against your will which, weird as it may be, makes you think about yourself more deeply and honestly.

You read Henry Miller because there’s no other writer out there like him, then or now. Because he refuses to back down, avert his eyes or look away from Reality. From What Is. Because he doesn’t have anything to prove; he only has himself to offer.

And we want him.

I do, anyway.

Miller, like most iconoclasts, lived to spite society’s status quo. All good writers do, it’s in the dna. I haven’t encountered any who don’t.

The only other comment perhaps contrary to this piece is that you may have too narrow an idea of what feminists were or are. We read Miller, Hemingway, Faulkner, Steinbeck but also Collette and Anaïs Nin. We loved men, just refused to be anything other than equals. Given our parents generation that was taken as aggressive. I sense you think so too, which limits you to the borders of those male writers you cite.