Henry Valentine Miller is one of the great unsung heroes, one of the finest rejected writers of the 20th century. Rejected, that is, by the “insider” literary establishment. Why? Because his books—mostly penned and published starting in his 40s—were considered “obscene.” Even now, in 2023, I find some of the language shocking. His liberal use of the word cunt is, even now, pushy and aggressive and inappropriate.

But hasn’t that often been the point of great literature? To push past boundaries of propriety, piety and good manners? I think of classics like J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, which, unbelievably, we were forced to stop reading at my private college-prep high school in the year 2000 due to parents’ complaints. Or anything by, say, Frank Norris in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Or how about H.L. Mencken. Nietzsche. Faulkner. Even Dickens, in the way he portrayed brutal realism.

Literature was never a highly educated, sweetly sophisticated, upper-class phenomenon. It’s strangely become that today, mainly because only a tiny fraction of genuine, serious “writers” exist. Now it’s all about streaming and YouTube and social media and podcasts. How many people—especially under 30—even read anymore? And, of those that do, what are they reading? Ideology has so infected the publishing industry that we’re floating on the most Orwellian moment in books in American history. And then of course you’ve got legal book-banning by the Republicans, and cultural banning and cancellation from the fringe-Left. Miller, like Allen Ginsberg in the 1950s, was on the forefront of the legal/obscenity/free speech movement in books. His Tropic books were mostly banned in the States until 1961, having been published by a small press in France in the 1930s.

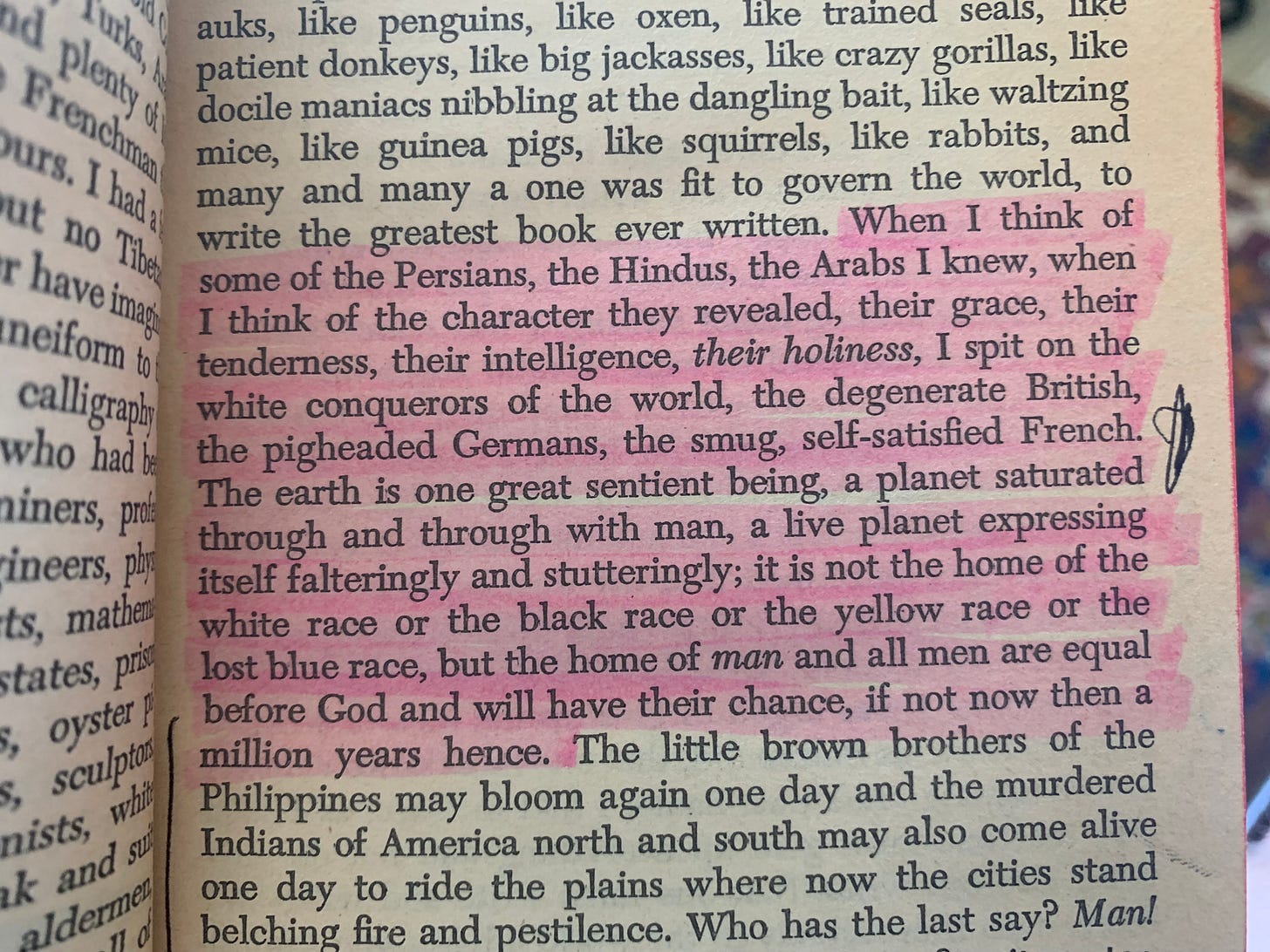

But if you’re the kind of quick-to-judge person who dismisses Miller simply because his prose can be “pornographic,” I think you’re missing out on a brilliant mind. Even the harshly critical, fiercely independent-minded George Orwell, in his essay collection, praises Miller. Ditto high praise from Norman Mailer. The thing is: The highly sexualized language is a thin veil protecting a rich, wildly imaginative mind. No writer can use myth, metaphor, simile and physical description to detail the inner landscape of a man like Henry Miller.

His ability to break down his complex, nuanced, intense thoughts is uncanny. His genuine desire to crack open both his brain and his heart and share it with the reader is unrivaled. Part poet, part angry belligerent child, part spiritual soldier, part lost soul, he ravages our senses, spikes our sympathy, arouses both our ire and our pity, and makes us want to hug him and sock him in the nose all magically at once.

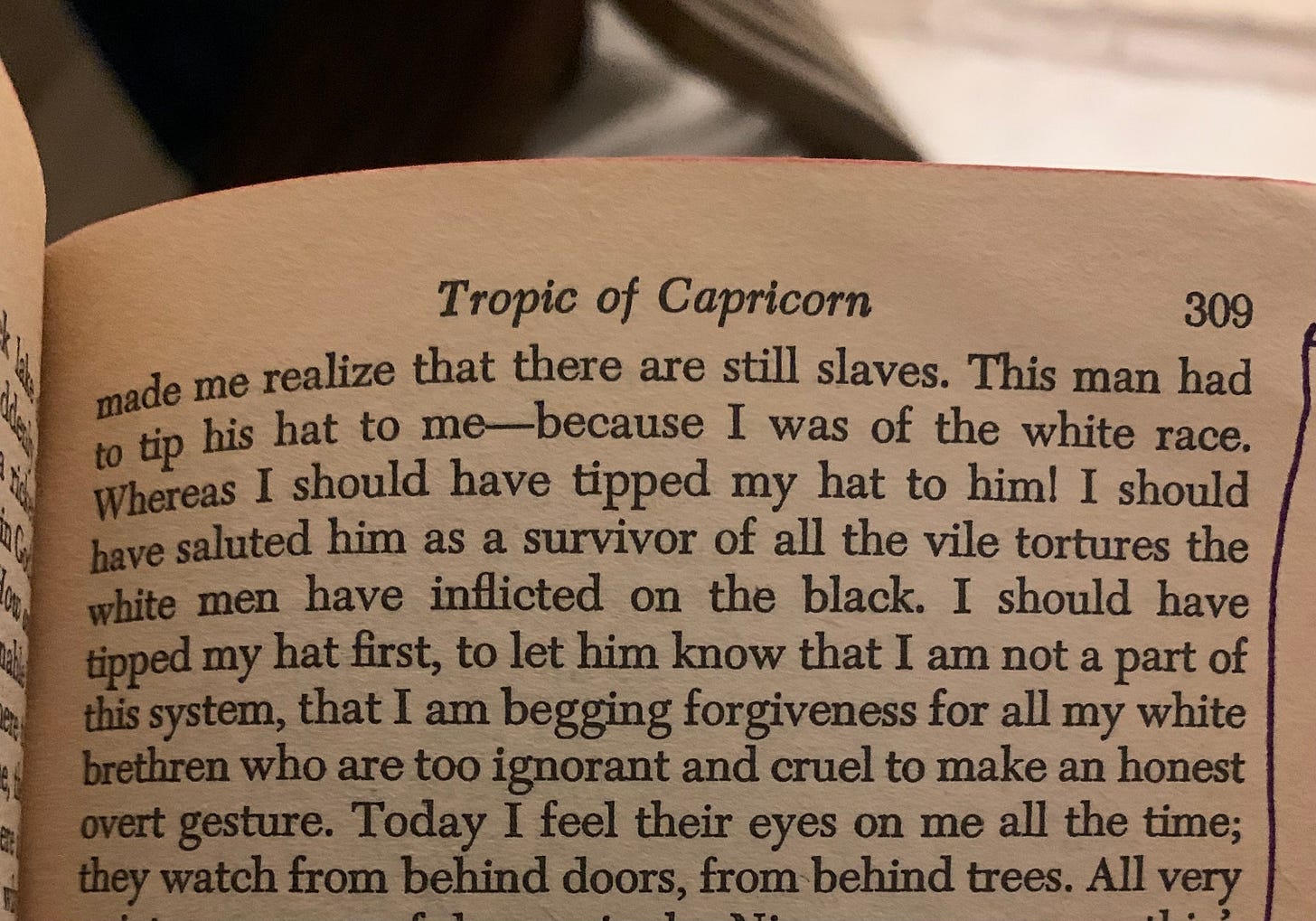

I won’t defend Henry Miller the man. Henry Miller the artist, yes. The seer, the visionary, the spiritual witness, yes. But not the physical man himself. He wasn’t good or admirable. You wouldn’t want your kid to turn out like him. He basically ditched his wife and child for his art. He slept with anything that had a pulse. He contemplated rape. He spent time with derelicts who are violent towards women. He thought mostly of himself, and constantly. He stole, borrowed money without returning it, and focused exclusively on his writing to the point of forgetting other people entirely. On the flip side he rejected the obsession with conventional identity, claiming both male and female traits, and he eschewed white racism against Black people. He mocked Jews and yet had many Jewish friends.

He was definitely a man of his time (born, amazingly, in 1891), and a native New Yorker, growing up in both Manhattan and Brooklyn. He did not come from a family with much money. He enjoyed wandering the streets, seeing the people, observing the urban anarchy unfolding around him. He couldn’t keep a job longer than a couple of months most of the time. He hopped from job to job to job, always dead-end projects. He was constantly in debt. He knew, from a fairly young age, that he had books within him, he just didn’t know how to get that out, how to create externally from what was bubbling, burning inside him, how to make the internal external. Until he left NYC for Paris in the late 1920s, in his late thirties by then. He got a late start creatively, at least when it came to externals.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Michael Mohr's Sincere American Writing to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.