Interview with Lori Mohr, author of The Road at My Door, No Ordinary Life, A Million Tiny Steps, and Child Soldier.

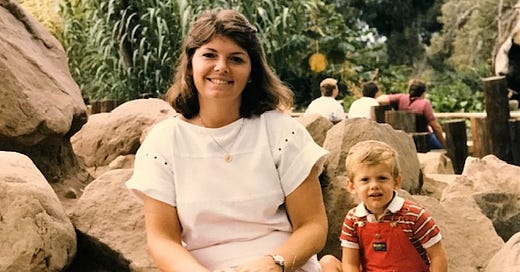

(Lori also happens to be my mother)

Please consider:

1. Subscribing if you haven’t yet (this story is paywalled…most are free)

Sharing this post (if you like the story)

“Recommending” “Sincere American Writing” on your Substack page.

Thank you for reading, everyone!!!

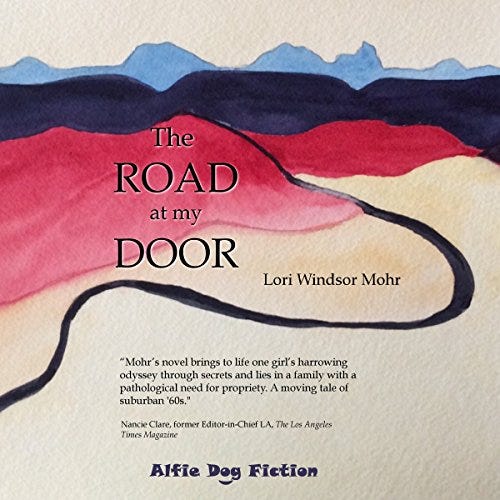

Lori’s Bio: Lori Windsor Mohr, a native Californian, grew up in Pacific Palisades during the 1960s. After earning a master's from UCLA, she worked in mental health and taught nursing while continuing to write. Dozens of her short stories have been published in journals and online. The Road at my Door follows protagonist Reese Cavanaugh on a dark journey to save her family without destroying herself. Set against the backdrop of the Cold War and sexual revolution, Mohr examines the decade of upheaval that set the stage for who she is today. In Reese Cavanaugh, she draws on her own experience with depression as one way of fighting the stigma still associated with depressive illness.

###

Probably a large part of the reason I became a writer is due directly and indirectly to my mother. Besides being a nurse, a nursing instructor, volunteering with the National Disaster Search Dog Foundation, as well as volunteering for the past 16 years as first a docent and then as editor of the newsletter for The Santa Barbara Museum of Art, she has always been, at heart and in soul, a writer. My mom published her first book (a novel), The Road at my Door, in 2015. Prior to that she wrote a column for Pug Talk Magazine.

Over the past seven years she has ghostwritten three nonfiction books, A Million Tiny Steps, No Ordinary Life, and Child Soldier, all three connected (in different ways) to African history. Growing up my mom read the classics to me at night. She had a lush, profound library for me to peruse. Once, when I asked my mother what the rules of writing were, she proclaimed, “There are no rules; you can do whatever you want.” While not necessarily technically true, the spirit of the sentiment started a fire under my literary ass that never subsided. In short, my mom changed my life. Her novel (largely but not entirely based on true events) helped me explain myself to myself, grasping on a granular level where my mother came from and what her struggles were. I went through different but in some ways similar struggles myself.

The Interview

###

Michael: When was the first time you remember being curious about writing? Your mom (my grandmother) was a big book reader, right? Did it come from her?

Lori: Reading was my mother’s salvation in an unhappy marriage with three kids. My memory of her face has a book cover over it, lost in the current selection from one of her three memberships in Book of the Month Club. After school I would find her on the couch immersed in Pearl Buck, or Nabokov, or Henry Miller, Ayn Rand, Truman Capote, Leon Uris, Graham Greene…the list goes on. The experience didn’t inspire me to read. I resented those novels for taking her away from me. It was only in high school that an English teacher inspired my love of reading, starting with poetry—William Butler Yates, Gerard Manley Hopkins, then Hertzog, Hesse, Austen.

The irony is that my writing came from my mom, who wasn’t a writer but should have been. I don’t know if it was her voracious reading or her innate personality, probably a combination, but the woman could gloriously construct a narrative capturing the essence of an ordinary moment. Whether cooking dinner or chastising us kids for some misdemeanor, she could take an ordinary occurrence and elevate into an enthralling story. My dad dismissed it as embellishment, exaggeration, the byproduct of too much reading, or an overactive imagination.

I now know that talent as storytelling. And she was a master. Listening to her talk, how she pulled out just the right word to fit, the right build up, the emphasis, I loved just hearing her.

When my parents had people over, the room lit up when she took the floor. Words, phrases, tone, pacing, voice—all the elements of writing were at play in richly detailed scenes, descriptions of something from that mundane world she was trapped in but longed to escape. Funny, quick as a whip, the stories were just snippets—what happened when she stopped for gas or whatever, like blog posts today—spun to life.

It goes without saying that my mother was a terribly flawed person. And I paid the consequence in a lifetime struggling with depression. Five decades later I finally understand that she was the person who inspired my writing. Your dad’s oncologist likes to offer the perspective of ‘no free lunch’ in discussing treatment side effects. Every option comes at a price, some drawback. For me, as much as the struggle with depression has weighed me down, the love of writing has lifted me up, in equal measure.

It’s no accident that my brother and I are both writers. And if you’re generously crediting me with inspiring you, then you too have carried that same weight of depression on one hand, and been the beneficiary of your grandmother’s largesse on the other. No free lunch, right?

Michael: How did you start writing about pugs? When and how did you begin writing a column for Pug Talk Magazine? Did you enjoy writing fiction or nonfiction better?

Lori: You were in high school when I got my first pug, Lucy Magillicutti after Lucille Ball. You no longer welcomed big strong hugs, so Lucy was my empty nest solution. For Christmas that year, your sister gave me Margo Kauffman’s book, Clara, The Early Years, about her pug. It hit me hard—I can write like that! She wrote the same way my mother talked, funny stories of ordinary life. That same year I also got a subscription to Pug Talk Magazine, which amazingly had won two national Best of Breed Journals awards. I submitted a story, and they published it. For two years I was a feature writer.

When my mom died, I wrote about it in a story complete with deathbed scene in which Lucy acted as a canine bridge to connecting after a ten-year estrangement. It was a risky submission for the tone of Pug Talk Magazine. Not only did they publish the story, they hired me as staff writer, which I was for six years. Other stories included 9/11, my time as a volunteer with the National Disaster Search Dog Foundation during the weeks that followed the tragedy when a grieving nation called in to donate after seeing our dogs at Ground Zero. Those stories showed me that I could write in a whole other style, more memoir than short story anecdote with an upbeat ending.

Michael: What led you to writing your debut novel, The Road at my Door? You won a short story contest first, right? Can you tell us the basic story of this novel? How much is real life, how much pure fabrication? Did your parents read it?

Lori: The motivation was that I knew it was a good story. I just didn't know how to tell it. Memoir? Narrative nonfiction? The agent who eventually represented my memoir couldn't sell the book because it wasn't the right book. I had yet to figure out the best form that would offer readers an emotionally satisfying experience.

What kept me going was belief in the story, and the realization that if I wanted to tell it I had more to learn about writing. That book took me over a decade to write, a decade of classes and workshops and manuscript rejections before I found my voice as a storyteller and traded my platform for whining into a platform for writing about the toxicity of family secrets.

Michael: The novel feels very autobiographical for the most part. Can you comment on that? How much of this is fact, how much fiction? It is in fact a “novel,” so we assume much is made up, but we know from reading the author bio that you dealt with serious depression as a teen, like the protagonist, Reese Cavanaugh. Like Hemingway said, we often, “Write what we know.”

Lori: Writing what we know is one thing, writing what we want to convey is another. I didn't want to write about me. I wanted to write about the experience of depression, the destructive power of secrets. Memoir seemed an obvious choice. However, that form had limitations. It's true memoirists use a novelist’s tools to bring readers into the moment: dialogue, scene, descriptive detail, all of it, like Jeannette Walls’s The Glass Castle or Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar. But as a literary form, it didn't allow the creative freedom I needed for writing the most compelling, fluid, readable story possible. In Road I manipulated time by compressing it, I reconfigured the family, combined two characters into one, left out a marriage, all decisions for building tension, keeping the emotional focus where it needed be. In the end, this wasn't about truth versus fiction. It was about what I hoped readers would experience.

The character of Reese Cavanaugh allowed me to create the best version of me that would move the story forward, draw readers in. Reese is prettier, smarter, funnier than I ever was! And she became her own person as the story evolved. I hated saying goodbye. In fact I kept tweaking the manuscript because I didn't want the story to end. Reese Cavanaugh brought magic to the writing, taking me to that sublime gray space between reality and illusion where you find creativity.

If I've written well enough, readers will be too enthralled and moved to care much whether the story comes from real life or not. They'll go where Reese Cavanaugh leads them, connect on a feeling level with their own experience. That's the emotionally satisfying experience I wanted to offer. I couldn't get there with memoir.

Michael: What was the experience of marketing your book like, and of working with a small publisher? Did you feel satisfied or not with a small house, and with not having an agent (though you had had one prior)?

Lori: I was giddy with glee to have found a publisher, in London no less. The first agent I’d had—Agnes Birnbaum at Bleeker Street Literary—wanted me to fictionalize my nonfiction book, Dog Alert: The Search for Life. It felt like betraying our dog handlers for potential sales. I was so naïve but broke the contract. Boy, did that break my heart.

That’s when I started Road. And a decade of rejections while I learned to write the way my mother told stories. In the middle of minor rewrites requested by the editor, my father died. I asked for a six-month extension on the deadline. In that six months, no longer needing to protect my dad, I completely rewrote the book, ditching the Disneyland version and going with the real story. What an incredible experience! It was such a satisfying experience that even had the publisher no longer wanted to go with it, a real possibility, I was willing to lose the contract. Road was the book I was meant to write. Sobbing my way through the manuscript, I knew it was good. My mom would have been proud. She might have even seen the love.

Michael: Tell us about how you got into ghostwriting. What is the story of the three books you wrote centered around Africa? (One is about the child soldiers in South Sudan during the Second Sudanese War; one is about a doctor in South Sudan; and one is about an American woman and her husband as diplomats in South Africa during Apartheid.) Some of the pros of ghostwriting? Cons?

Lori: I call it co-authoring, as my name is on the books, a clause in the contracts. The first one unfolded when I met the event planner for a writing conference I attended in San Francisco. You had introduced me to your writer friends and Mary Byron overheard us talking. About dogs. Over a glass of wine she told me she had an incredible story to tell about life as a foreign service worker with her secret service husband in South Africa during Nelson Mandela’s tumultuous two years before the first democratic election in which he was elected president. But she wasn’t free to tell the story until her husband retired from the State Department. Five years later, she approached me, and I wrote her story, No Ordinary Life.

A friend of mine read that book, a surgeon who had gone to Sudan with Doctors without Borders to set up a rural surgical clinic the year before South Sudan gained independence as a separate country in 2011. Ken Waxman returned to Santa Barbara and started a nonprofit, Future Doctors of South Sudan, so moved was he by the experience. The mission is to offer scholarships to med students waylaid in school due to lack of funding. He connected me with eight of the students. I worked with two, and one had to drop due to scheduling conflicts. The other was Hellen Onyango, the only woman med student in a country with an 88% illiteracy rate the year she was born. We did everything via email over two years as I told her story of growing up in Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya after walking the countryside for two years trying to stay one step ahead of the enemy during the Second Sudanese Civil War she was born into in 1989. A Million Tiny Steps is her astounding story.

Child Soldier came about through one of FDSS’s students who had a friend ‘with an incredible story.’ After reading his notes, I agreed to write it. Incredible is right. I was so moved that in spite of not wanting to go back into that war after all the research I had done, after Hellen’s book, the pain of knowing what happened to kids, women, old folks—I agreed. His life story begins at age eleven when he runs away from his village to join the Red Army—think Hitler’s Youth Army with all the requisite brutality—and doesn’t get back to his mom for eleven years. It’s a powerful story that brings me to tears every time I talk about it.

When I asked Kuot for images for to include in the book, he sent me one of his mom holding her grandson, Kuot’s son. When I opened the email image, a sob surged through me, looking at his mother, knowing what she had been through all those years not knowing if he was dead or alive. It’s quite a journey he takes, on every level.

Michael: How do you feel about writing in contemporary times? How has it changed since you started many decades ago? What is the biggest lesson you’ve learned as an author?

Lori: The literary marketplace has changed so much, even since my first book. I’m no longer writing fiction, and that’s fine. Regardless of genre, I am a writer, always will be. Getting The Road at my Door published was so satisfying. And writing other peoples stories—especially Child Soldier and A Million Tiny Steps—moved me in profound ways. I think about Kuot, about Hellen, about survival and about flourishing. They are heroes in my canon of literary experience. Last year I was approached via email by one of the Lost Boys of South Sudan from the 1990s.

Their story was brought to the world in a series of interviews on 60 Minutes, exposing the tragedy suffered by thousands of (mostly) boys who were orphaned when their villages were attacked in the Second Sudanese Civil War. These children, ranging in age from 6 to 14, wandered the country for two years before finding shelter in the Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya, where Hellen Onyango grew up.

Now 50, one of these boys had read Child Soldier and wanted me to write his incredible story, equally as powerful as the other two stories. I turned him down, the irony not lost on me. Today’s market would find his story appealing. But writing again about the trauma of war felt daunting—the first two books were tough to write—and I no longer have a stomach for the chase, the pursuit of an agent, beefing up the platform, all of it. I never marketed my books. You won’t find reviews on them, except for Road, which my publisher marketed. Social media as a component of being published is a deal breaker for me, and that is the nature of publishing these days. No free lunch.

As a docent at The Santa Barbara Museum of Art for almost 17 years now, my writing is art focused, giving lectures in the community. Research, writing, public speaking—my three favorite pursuits, have coalesced into an enjoyable way of life.

What have I learned as an author? Oh man. That’s a good question. In my 20 years of writing professionally, the joy was always clouded by the Marketing Question. How to write the book without writing for an agent/publisher, that was difficult. What would they like, what would be hot for today’s market. My strategy was to have a dozen friends in my head as I wrote, my target audience to keep the editor in my head at bay until I had written the core of what I wanted.

That’s where working with a good editor comes in—it’s a true partnership. A talented editor—gee, I happen to know one too—can make all the difference between a good story and a marketable one. In my early years of writing I did not grasp that. I was too defensive, too insecure. But to use a tired sports analogy, scores are made with the help of teammates, assists that set the field for one person to tick the score higher. The process of writing is singular, which is why we writers experience such loneliness.

But the process of birthing a polished finished product needs that assist. How I wished I’d had that awareness two decades ago. The other lesson I learned is to embrace rejection. Rejection hurts, but as long as you have your hat in the ring, you’re getting valuable feedback, you’re honing skills with every disappointment. You’re participating with the best company.

I’m proud to be among you. Keep writing.

###

To buy Lori’s books CLICK HERE.

What an inspiring story. Your mom is the best kind of writer, one who is true to her gift and uses it to understand herself, and the world, better. Everyone could learn from her journey. Thank you for writing this.

What a great interview and what a wonderful tribute to your mom !