Jonathan Sperber’s Karl Marx: A Nineteenth Century Life

Anecdotes and Tidbits #2: Intellectual Thoughts on Things

*I want to mention Matthew Long’s wonderful Substack—which you should all subscribe to—BEYOND THE BOOKSHELF. He recently wrote a lovely, honest review of my debut novel, The Crew. (Think Catcher in the Rye meets The Basketball Diaries meets the Sex Pistols and Ramones; punk kids who get into trouble but love literature and philosophy.) Buy my book here (please review).

**Once finished with the book I’m discussing in the following essay, I plan to write an in-depth full book review. This is just a snippet for now. Call it a cliff-hanger 😊

~

I’m about halfway through this biographical beast (2013). I will most certainly write a full book review when finished. Reading histories by experts in our current era (2024) is always amusing and absurd, full to the brim with ironies around every corner, because very few people read anymore, and because of the psychological and very literal fragmentation of (social) media, and the intellectually lazy and patently ideological manner in which most people—particularly polarized Americans—focus their energy on “picking sides” versus critically and seriously thinking independently about deeply complex, nuanced ideas.

For example: Marx was deeply antisemitic (though Sperber, clearly more on the side of Marx than against, attempts to argue the opposite, while simultaneously admitting that Marx clearly said that the problem with capitalism is a Jewish problem). Even more ironically: Marx himself was a Jew. His father had converted to Protestantism and little Marx had done the same at age six. Jews—as almost always and everywhere globally until the mid-twentieth century—did not have the same rights and privileges as other citizens in society. The liberal intellectual ideas predicated on the Enlightenment which Marx initially very much grew out of stemmed from the liberal Protestant milieu of his time.

Another irony: Marx himself was very much of the dreaded (in his mind) “bourgeoise.” He was often loathed by the actual proletariat (working class), and even once was chased out—along with his friend and coauthor Friedrich Engles—of a communist meeting by said proletariat. The working-class often saw Marx as a lazy, spoiled intellectual, a Utopian who was not one of them. Equally ironic: Marx often courted “capitalists,” including major investors, in order to start various newspapers, including The Rhineland News and The Franco-German Yearbooks, in which he was often both editor and writer.

Marx, after the 1848 (largely suppressed and semi-failed) revolutions that swept across Europe, was often in conflict with other socialist and communist groups; there was a deep splintering which culminated in trials in Cologne in 1850. Marx put “The Movement” ahead of both himself and his wife (who came from an aristocratic family but was also a dissident writer herself) and six children. They often lived in excruciating poverty, not to mention brutal debt. Marx was no doubt a stringent—some contemporaries and friends even said “tyrannical” and “dictatorial” man in his political and personal life. He had a massive ego—think Freud—and he wanted to control the direction of the revolutions to come in Europe.

Originally, Marx felt certain that capitalism was essential, necessary, to the foundation of what would phase slowly into communism. First the nobility would be taken down by the bourgeoise (he saw this as being what the goal of the 1789 French Revolution had been), then the proletariat would foment a revolution taking down the bourgeoise. There would be a “dictatorship of the proletariat” with a state-run economy. Landowners would be stripped of their land. From each according to his wants, to each according to his needs. The class structure of both the nobility and capitalism would be summarily abolished; instead, all citizens could do as they please, work whichever jobs they chose to work.

Looking back now it seems hopelessly naïve and utopian, but you have to remember the historical context. Marx was born in Germany in 1818. (During the time of German city-states, well before the national unification of Germany under Bismark in 1871.) His youth was a time of revolutionary fervor. Kings everywhere trembled. The French Revolution had been a global warning to all autocrats…and yet the end result had been the reign of Napoleon.

Yet change seemed to hover in the air, just below the surface. Secret societies arose around Europe. Socialism and communism gained in popularity. The desire for freedom of speech, press, religion, etc, all of which Marx supported, flourished in the 1830s and 1840s. (Marx was critical of the Jews but believed in their access to full civic rights.) It was a time of rising newspapers in England, for example—where freedom of speech, press and religion were solid within the liberal constitutional monarchy—such as The Economist, the London Times, and The Daily Telegraph, among others.

Marx—ironically—both believed ideologically in freedom of speech and what we today might call “viewpoint diversity,” and yet he often flew into paroxysms of rage when others in his orbit disagreed with his views. Hence the complex inner conflict within Marx as both ideological liberal and yet personal dictator.

I think all of these ironies are brilliant and hilarious and they easily demonstrate exactly why Marxism and communism have never and could never work out in the real world: They forget the vagaries of Human Nature. Look no further than Castro in Cuba (sure, they had high literacy but mass poverty), Stalin (who killed as many as possibly 20 million people during his reign from 1929 to 1953), Ho Chi Minh (who murdered between 200,000 to 900,000 during his rule in Vietnam), Mao Zedong in China (who killed masses of people in the Great Famine, and brutally repressed freedom of speech and other basic civil rights), etc.

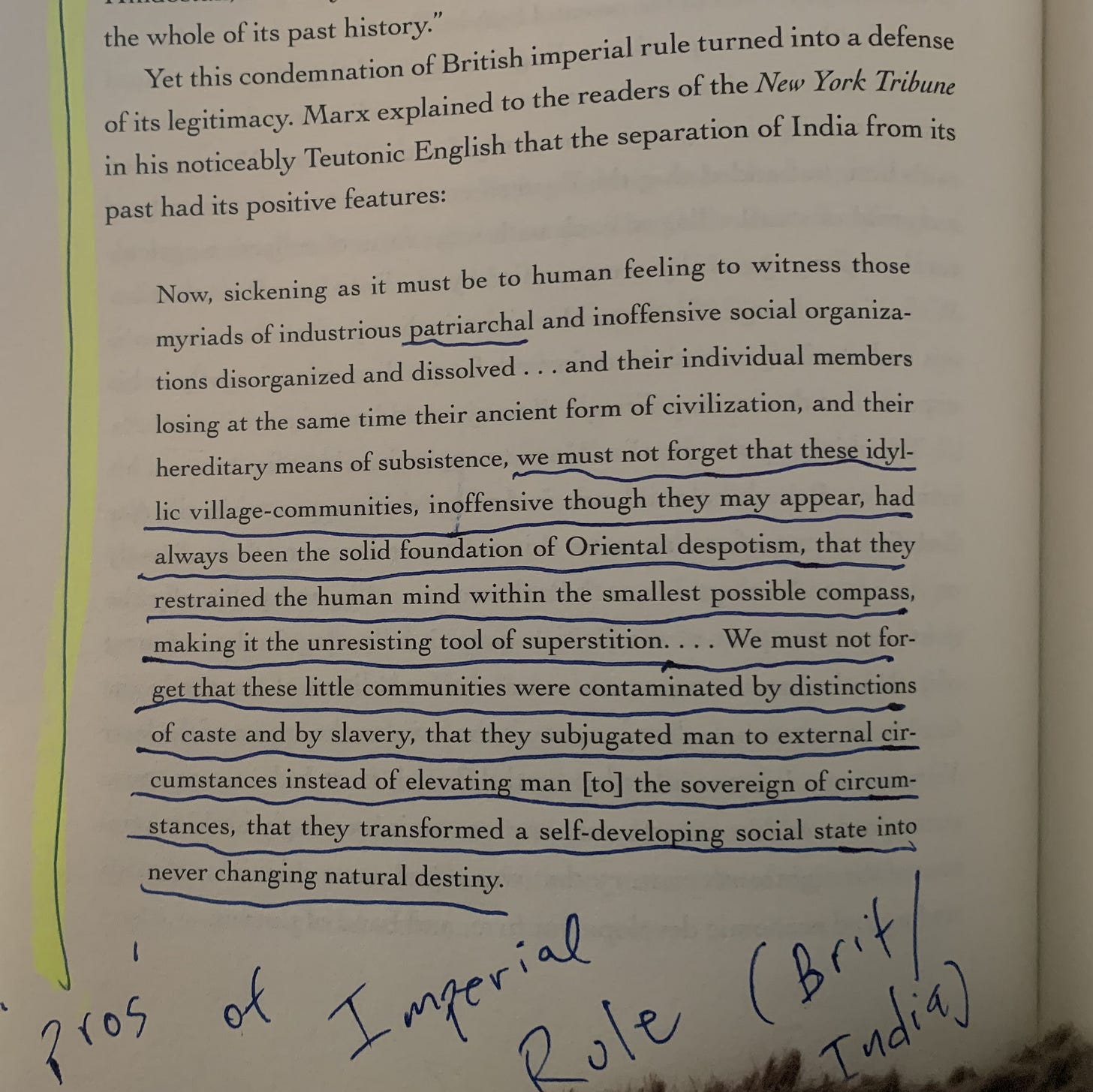

Here's a supreme example of the irony between genuine 19th century Marxism—Sperber continually discounts “presentism” in favor of understanding the complexities of Marx's thought in his actual era—and what young Leftist “Marxists” believe in today. The topic of imperialism and colonialism. Believe it or not, Marx actually believed that British rule in Asia—specifically India—was, for the most part, a good thing, writing that though capitalist imperialism had its deep flaws, it also helped Westernize Asia which he found necessary given that things such as caste, rigid class structures, superstition, and even slavery existed in these older pre-civilized societies and needed to be eradicated by Western power. (Britain had ended slavery in 1833.) This would include—this is me talking now—not only India but Africa, Native Americans in North America, and many other groups.

This is a profound and humorous maximum gap between supposed progressive socialists/Marxists now and what Karl Marx the actual thinker wrote, thought and believed. See photo below.

The problem is that human beings are human beings. They seek, crave ultimate power. Without restraints, they rise to unstoppable heights. They seek total control. This has been historically true whether it be with monarchs, fascists or communists/socialists. Capitalism is of course flawed and deeply imperfect. Like all systems, it also creates varying degrees of oppression, poverty, unfairness, bigotry, a sense of social futility, imperialism, etc. And yet, as many historians and politicians have remarked: It seems to be, as of now, the best of the options available.

The hard truth is that human beings are organically, inherently hierarchical. Look at the animal kingdom. More specifically, look at our closest ancestors: Chimps, who we share 98.8% of our DNA with. With chimps we see, in the wild, males fighting for domination and power and control of the group. We see some chimps excluded. We see differences between males and females, physically, psychologically, socially, etc. This is simply normal. I’m not saying it’s “good,” or “bad.” I’m saying it’s natural and inherent. That doesn’t mean we as individuals cannot alter or adjust our behavior; obviously most of us do this on a daily basis to varying degrees. But when it comes to groups, things are different. A change occurs.

Group psychology is a fascinating subject which I will not delve into in detail here. But it’s clear that groups of people—ditto groups of chimps—clearly act differently than when they’re alone. Look at our current historical and political moment right now, in 2024. How does someone you disagree with act if you get into a random conversation at a local bar or on the subway or at a coffeeshop, versus how they act when you’re dialoguing on social media and they’re aware of all their online friends seeing the exchange?

There’s a massive change.

How does a teenage boy act alone versus with a gaggle of his buddies? How do girls act alone versus with their clique online or clumped together at school? Individual behavior changes when groups form. I haven’t read the book but the title of Douglas Murray’s book, The Madness of Crowds, seems to sum it up nicely.

When mass groups of people come together to form organized societies—which humans did roughly 10,000 years ago, shifting from hunter-gatherer societies to agricultural non-mobile villages and farms—behavior changes. There is a necessary surge for control. Groups battle each other—politically, psychologically, physically—and one group lands on top. Later, of course, that group falls and another one rises. These are called revolutions, or simply organic measures of natural political and sociological change. (Often interpreted historically within the grotesque but inevitable framework of military conflict (war).)

But the idea that we’re going to live in some pure worker’s paradise where the state owns the means of production, the aristocracy is destroyed, and everyone lives in egalitarian paradise: This, clearly, was never realistically going to happen. Marx was important as a thinker, a polemicist, an intellectual soldier in a very specifically 19th century battle Galactica which was fighting something both broad and specific: The coming end of European monarchies. His mistake was thinking that capitalism was only the first step and that communism would naturally follow.

We see the young Woke lefties nowadays proclaiming a sort of pseudo-return to Marxist ideas…sort of. But Marx was obsessed with class; economics; the proletariat. In our time now the New Radical Left has completely abandoned the working-class—especially working-class Trumpers—in favor of racial and gender identity politics. It’s a deeply unfortunate misunderstanding and misrepresentation of Marx and his ideas.

Marx was always essentially liberal in his thinking, especially in his early formative years, before, during and shortly after the 1848 revolutions. He grasped the importance of freedom of speech and press. He believed in the open, free market of both goods and ideas. He understood the “brotherhood of man.” He fought for universal “manhood suffrage.” He grasped slow change (early on, until his early thirties) and realized the necessity of liberal capitalism as an initial first step towards his notion of political paradise.

Not so the young’uns today. They want absolute and total change, and the change they claim to want is fundamentally anti-Democratic, un-American and superbly ahistorical. Luckily, every generation pushes back against the one that came before it. Already we see many in Gen Z dropping identity politics for something new, fresh and different.

Could that thing be, once more, independent critical thinking?

Perhaps.

We had it once. It’s possible we could reach it again.

Great article overall except I don't understand the second to last paragraph. I don't see Marx as ever being liberal in his thinking, especially not classically liberal. There's no way he was a liberal in 1848 when he had published the incredibly racist book "On the Jewish Question" in 1844.

Very enlightening .