*Please consider:

1. Subscribing if you haven’t yet

Sharing this post (if you like the story)

“Recommending” “Sincere American Writing” on your Substack page.

Thank you for reading, everyone!!!

###

There’s an old myth piled upon by a new contemporary myth about Art. The old myth goes something like this: In order to be a brilliant artist, you must suffer egregiously; you must be an addict/alcoholic; you must struggle incessantly with depression, melancholia, loneliness, desolation, perpetual solitude, fear.

The new myth, conversely, says, The Old Myth is Bullshit. It says, No, you don’t have to suffer erroneously just to succeed as an artist. That’s an ancient, unhelpful, toxic manner of looking at Art, life, manhood, womanhood, adulthood, etc. You can be perfectly happy and create good, important, relevant, impressive Art.

Me? I think there’s some truth in both, and some bullshit in both. I do not subscribe to the Binary All-or-Nothing, Everything is Either/Or attitude which is stupidly trendy in our current cultural and political and artistic contemporary moment.

Here’s the truth: Historically-speaking, most profound, celebrated artists (when I say “artist” here I’m using the word in its broadest sense, which includes visual artists but also writers, musicians, dancers, etc) have been—even in modern times—riddled with psychological issues. Not that I am either known, celebrated, or a genius—haha—but I relate to this. Life for writers and painters in particular has never been easy. When I say “life” I mean that both literally/externally and, more pressingly, internally. We artists—if I may deign to refer to myself pretentiously as “an artist”—are generally soft, sensitive folk. We notice details most others don’t. We tend to dislike typical, conventional lifestyles and jobs, the dreaded “9-5.” We struggle with basic things most “normal” people see as the simple, easy day-to-day.

Is this every artist? Of course not. But, having read enough autobiographical novels, and enough biographies of writers, and having my own experience to pull from, not to mention the lived experience of artist friends, it seems beyond obvious that most serious, ambitious artists suffer. Think of some of our biggest names in painting: Vincent Van Gogh; Picasso; Toulouse-Lautrec; Francis Bacon; Jackson Pollack; etc. And writers: Hemingway; Fitzgerald; Steinbeck; Paul Auster; Sartre; Kierkegaard; Kerouac; Baldwin; Plath; Dickenson; Stephen King; Raymond Carver; etc. Jack London drank himself to death. David Foster Wallace, for a more up-to-date example, wrote startlingly and gorgeously about depression and suicide and then hung himself in 2008. We lost a good writer.

On the flip side: No, I do not believe this suffering is a “requirement” to be an artist. But it does often seem to come with the territory. There seems to be a sense of mockery nowadays when newer writers/artists discuss the Old Myth. In “Big Magic” (admittedly a great book) by Elizabeth Gilbert, she makes this argument, suggesting that you can be totally healthy and happy while also doing well as an artist. (She also makes many practical suggestions, such as not expecting to survive financially off your passion, if that passion is your Art. Point well taken.)

[An incredibly talented painter-friend of mine, who also lives her life as Art, though thankfully not egregiously like Gauguin, Charity Lynn Baker, based in Manhattan, probably has some intriguing thoughts on this. She and I became friends when I lived in New York (2019-2021). See Charity’s art on Instagram HERE.]

I don’t disagree. It’s certainly possible. It’s happened historically plenty, I’m sure. Not every writer or every artist was a troubled disaster. But many of our best—and most fascinating—artists were people who suffered greatly. It makes perfect sense. I don’t think artists (I’m sure there are exceptions but in the overall) “act” depressed or “try” to suffer. In truth I don’t think people “become” artists; you either are one or you aren’t. Certainly you “arrive” into your artistic self, for sure, but I think that “artistic self” is already within you, like a coat just waiting for your body to grow into it. I’m talking about genetics; I’m talking about your unique inherent nature. Most people are not artists, and thank God, right? We’d all be doomed. We need most people to fulfill “purposeful” roles, such as doctors, judges, lawyers, cops, builders, etc.

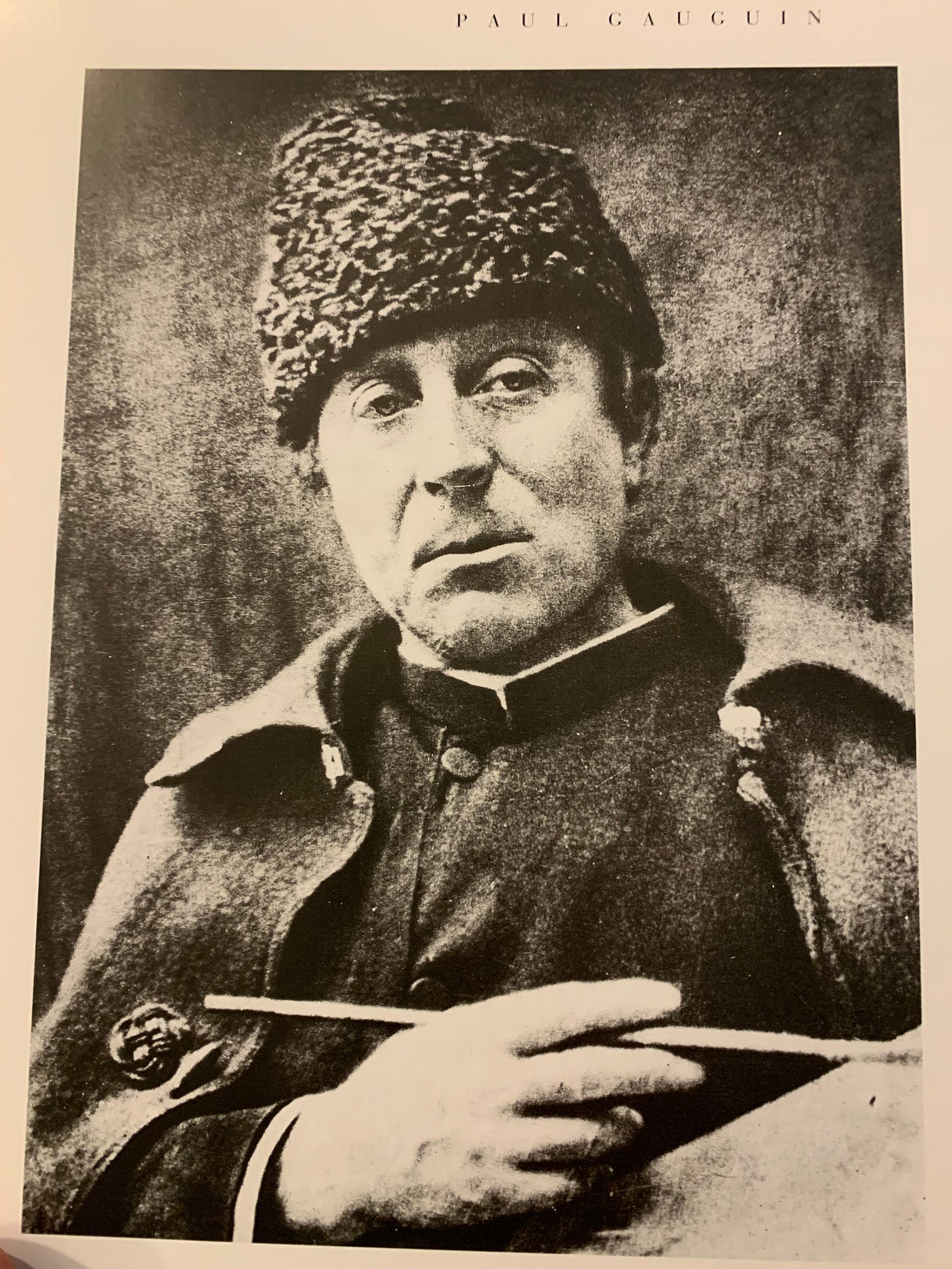

One such artist who most certainly did suffer greatly, and who I am now obsessed with, is one Paul Gauguin. I’m going to give you a relatively brief, broad-based biography of the man, and then argue my point (which is essentially that he was The Quintessential True Artist).

The biography I read, by the way, is “Gauguin,” by Henri Perruchot (1961). The photos I added to this post are from that biography, plus books of his paintings: “Gauguin” by Daniel Wildenstein and Raymond Cogniat; and “Paul Gauguin” by Maria Costantino.

Gauguin was born in 1848—the year of European revolutions and tumultuous political upheavals—in Paris. His grandmother had been Flora Tristan, a socialist thinker and author who’d made waves. Her family extended back to Peru. They had familial political connections there. Thus, Gauguin spent his brooding, lonely, imaginative, happy young boyhood in Peru.

Still a kid, they returned to Paris. His father, having taken a ship to Peru earlier, had died while on board. So it was only Paul and his mother, Aline. He went to school. He was weird. Different. Sensitive. When still young his mother, too, died. He thus got taken into the care of the Arosa family, connected to Flora Tristan’s side. Gauguin was intense, intelligent, and restless. Soon he joined the Merchant Marine as a pilot’s assistant and traveled much of the world for a couple years. After this he joined the French Navy.

Eventually, in his mid-twenties, in the early 1870s, through a family connection, he became a stockbroker on the French Bourse exchange. Surprising everyone—including himself—he did very well there. His life improved. He was making money. The market was rising and rising wildly. Things were only going up. Around this time he met and married Mette Sophie Gad, a woman from Copenhagen, Denmark. They fell in love. Over the course of time they had five kids together. This was also the time he began painting. He met another broker, Schuffenecker, who also painted and loved art and this man became good friends with Gauguin and took him into artistic circles, introducing him to fellow artists, art dealers, collectors, etc. It was during this time that he encountered the older artist who’d become his mentor: Camille Pissarro (1830-1903).

Also in the late 1870s the new Impressionist painters—who violently broke from the norms of classical painting conventional until then—were starting to form themselves into a semi-coherent, semi-official group and were showing galleries on their own, rejected out of hand by the Paris Salon and the Beaux-Arts, etc. Into this circle Gauguin was brought in.

Gauguin’s painting became more and more serious, more and more curious, and he became more and more dedicated to his craft. Slowly, the stock market became less and less interesting to him. He started to feel annoyed by it; resentful. His wife and kids mostly seemed to get in his way. In his deepest sense he was beginning to grasp that he was A Painter. But, then as now, artists were of course never taken seriously. So he continued to paint. He continued to show his work to a close circle of friends. He continued to work on the Bourse, against his heart and soul’s desire.

In 1882 the stock market crashed in France. Gauguin was 34. He quickly lost a lot of money and, simultaneously, ironically, decided to quit the market and became a dedicated artist fulltime.

And it is precisely THIS that makes me fascinated by and makes me gawk at the idea of Paul Gauguin. It would be just as insane to do this in contemporary times. Imagine some young 30s Venture Capitalist making bundles of dough every year quitting their job to become a painter or novelist fulltime. Everyone would think the guy was off his proverbial rocker! (And perhaps he would be.) Well, Gauguin’s wife certainly felt the same about Gauguin. And, look: Clearly, you can’t blame her! Once he made his choice, it wasn’t long before his money was dwindling fast. They moved a few times, trying to save money, but it was hopeless. Mette argued with Paul but it was to no use; the man was An Artist. Through and through. Eventually, in the mid-1880s, Mette took the kids and fled solo back to her native Copenhagen. And this is where Gauguin’s artistic journey truly began.

*(Above painting: “Whence Do We Come? What Are We? Where Are We Going?” 1897)

Now, I get it: Many of you are probably reading this thinking, What an asshole thing to do? He just quits his cushy job and throws his wife and kids to the dogs??? You’re not wrong to think this. I myself think this. What a narcissistic, delusional prick. What a dodo-bird. What an absolute selfish imbecilic buffoon. Reprobate. Degenerate, even. Loser. Waste of time/space/life. Can you imagine being his wife? His poor young kids?

And yet: We come back once more to the infamous debate: Can one separate The Art from The Artist. I, for one, definitely can. The truth is this: Most artists—painters, writers, musicians—lead “problematic” (to use a new lefty Gen-Z phrase beloved by the Woke), troubled, often chaotic lives. Artists are the genuinely wild, sometimes crazy, for sure interesting ones. They’re not after power or control; they’re after ultimate expression. Meaning. They aim to be understood, even if they never are. At a minimum they seek to understand themselves, that is, The Human Condition. Think about artists like Kurt Cobain, for example. Cobain would not have passed the Purity Tests of today. By a long shot. That’s because artists aren’t pure. They’re real, raw, authentic as hell.

Gauguin showed his developing work in the Impressionist galleries starting in 1879, carrying into the early 1880s. (The first one was solely a sculpture of his son, Emile.) He lost his money completely around then and suffered noxious poverty. This really titillates me as well: The guy is a stockbroker—making a killing on the market—and he gives up financial security; his wife; his kids. He throws all of it to the wind to live in total poverty and paint pictures. Now that is dedication. That is artistry. That is ambition. That is…mental illness? Superb stupidity? Perhaps. But that, if anything, might be only one element. The man was a genius. Not a genius in every aspect; he struggled with learning new languages, for example. But as an artist: He was a genius. Both in his painting and in his lifestyle.

Long story short. He connected with Theo Van Gogh, an art collector and dealer and Vincent’s brother. Briefly he lived with Vincent in Arles, France. They didn’t do well together and, after only nine weeks, Gauguin left, but not before being nearly attacked by Vincent with a straight razor, which Van Gogh then used to cut his own left ear off. Classy. (Vincent died at age 37 in 1890, mentally unwell. His brother Theo died just a year later.)

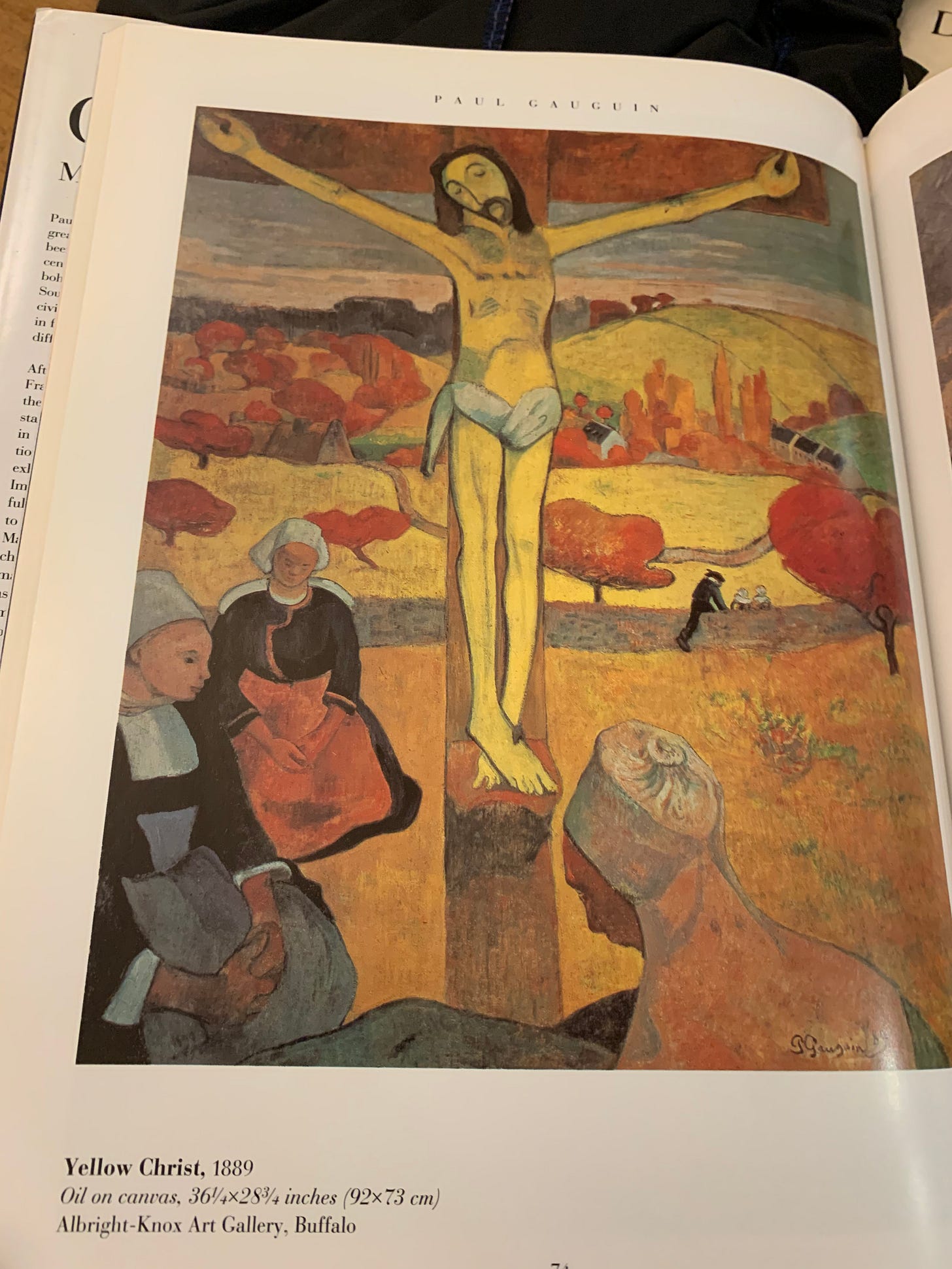

Gauguin’s life perhaps becomes most interesting in the later 1880s and throughout the 1890s until his death in May, 1903, at age 54. He started staying at a sort of non-official de facto “writers’ resort/retreat” in Pont-Aven in Brittany in rural France. Here he met many other painters making waves at the time, including Emile Bernard, who he later fell into primitive mutual hatred against. Previously, earlier in Gauguin’s painting odyssey, he’d found a mentor in the older Camille Pissarro, a classic Impressionist. But, as time went on, and as Gauguin’s painting began to slowly move through Impressionism into Post-Impressionism, Symbolist Art, Synthetism, Primitivism, and then finally into a new unique amalgamation altogether (painting which depicted less the realism than the “essence” of something, using colors and symbols and representations more than realistic direct depictions in the classical-academic style), he and Pissarro started to unglue from each other. The student was rebuking the teacher, as it were. Plato pushing back against Socrates, if you will.

Clearly, Gauguin had a fascination with anything anti-European, including travel and geography. His paintings were unanimously rejected by the outside world, and even to some degree within the Impressionists themselves. Degas liked his work, and they became good friends. He made some minor sales here and there. But most serious outside artists, critics and academics found Gauguin’s painting vile, uncouth, retrograde, childish, bad. (How common this is, also, with famous artists: They’re almost always rejected by The Official Players.)

And so he lusted for the anti-Western society; the anti-“civilization.” This led him first to Panama, then to Martinique, and finally to Tahiti, and, eventually, to the Marquesas Islands 881 miles northeast of Tahiti. His foot was fractured from a nasty fistfight with some sailors he and some painters had gotten into in rural France, and that continued to bother him. He had “eczema” (likely Syphilis). He’d gotten Dysentery. He was perpetually starving, broke, in debt, borrowing money, exhausted. He rarely spoke to his wife through mail. He almost never saw his kids.

He slept with other women and got a few of them pregnant. In Tahiti he lived first in Papeete, but soon realized it was filled with French authorities and felt too “civilized.” (Tahiti was a French colony still.) So he removed himself to a more rural, isolated area of the island. He literally lived in a thatched hut and wore a loincloth. He ate the local fruit. He painted. He sent mail slowly back and forth between Tahiti and Paris. His friend George-Daniel de Monfreid (1856-1929) was a French painter and art collector who befriended Gauguin and sold some of his paintings somewhat regularly, as did a few other friends. Some French officials bought some of his work here and there. But he was poor.

He was “married” (not really) to two “vahines,” meaning native women, meaning, actually, 14-year-old girls. *(This is another one of those “separate the Art from the artist” moments.) He got more and more sick. He kept painting. Later, after he fled to the Marquesas Islands, he for a while became a sort of unlikely revolutionary writer and “activist,” summoning his socialist-author grandmother Flora Tristan’s wild roots. He deeply criticized French colonialism and French authority, and questioned their exploitation of the natives a la unfair taxes, unfair rules and restrictions, the maniacal “Christianization” of the locals in church and school on the islands, the forcing of Western ideology, etc. The natives loved him. His hut had a sign out front that said, “Place of Pleasure.” He had parties. Locals came to look at the strange, fascinating paintings on his walls. They drank and became wild. He painted many local native girls/women.

Sometimes he made more money. Sometimes he sent some of that to his wife in Copenhagen. Sometimes he immediately paid off staggering debts. Sometimes he foolishly wasted it and gave it away. He was a child with money. (Another artistic trait, often.) His foot bothered him more and more. His (likely) Syphilis worsened. More native girls bore his children. He wrote a little magazine which circulated the island, criticizing the French power structure, and in the islands specifically the colonial military authorities. He was nearly thrown in jail.

At last, in the mid-1890s and beyond, he slowly started to become more known in Paris, more respected, more sought-after. People paid more and more for his canvases. He was the strange European anti-painter, anti-hero who had fled the continent and was living like a primitive in the Pacific. He also did ceramics and sculpture. An art dealer, Ambroise Vollard, back in Paris, bought many of his paintings for low prices and then sold them at a profit. But he made Gauguin an offer he couldn’t refuse: In exchange for a certain number of paintings per month, Vollard would pay him a regular stipend of 350 francs each month. Basically: He’d pay for the artist to live and paint exclusively without having to work a regular job or constantly be in debt. He wouldn’t be rich. But he wouldn’t be in incessant fear of poverty. Gauguin took the offer. (And it wasn’t the only offer; other dealers showed interest by then, too.)

Gauguin became known as the semi-crazy painter who’d left Western Civilization and had “gone native” into the unknown. It was the quintessential “Descent into Hell and Return” Joseph Campbell wrote about extensively. I can’t help thinking of Marlow in Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness,” both literally in some sense and of course figuratively, symbolically.

Was Gauguin a great man? I think this answer is pretty easy: No. He was a profoundly selfish, childish, angry, resentful prick, really, who left a wife and five kids for his own obsessive pursuit of Art, who impregnated several other women and didn’t help them with their children, and he slept with several or more native teenage girls, when he was an old, grotesque man in his 40s and 50s.

And yet. Still, I cannot and will not reject Gauguin out of hand. People—myself included, and most others; I have learned this the hard way—are very often complex, layered. People lie, cheat and steal. They hurt themselves and others. They hold deep, dark secrets. They wear a social mask they present to The World. (Thank you Facebook.) Think about #MeToo and all the writers, filmmakers, artists that exposed. Think about the media leaks. Conversations. Texts. Emails exposed. No person is 100% pure. That’s what makes us fundamentally human, fundamentally unique in the world. We have self-awareness; metacognition. We’re aware of our awareness; aware of our own impending death. This creates both joy and fear. Love and hate. Community and solitude. Growth and stasis.

I know I’ve made a TON of mistakes in my life. Many of them have been bad. Conversation-stoppers, even. In AA I know people who’ve killed, people who’ve gone to prison for decades. Men who have raped, who have harmed people in ways they’ll never recover from. But these people changed. Gauguin? Did he change? Maybe. Yes. No. I have no idea. He certainly had a “character arc” to use a fictive phrase. A beginning, middle and end. He did change. But did he morally redeem himself? Did he achieve redemption? As a man? No. I don’t think so. As an artist? Yes.

What fascinates me the most, about Gauguin, is that he was willing to take his passion all the way to the very end. He was willing—however morally egregious it may be—to leave behind his whole family, his close friends, his country, even his continent, for one singular purpose: His art. He died for it.

And for that, I have the utmost (admittedly conflicted) respect for the artist that was Paul Gauguin. Was he an irreproachable asshole? Probably. At least much of the time. Arrogant, self-involved, navel-gazing. Sure. Yes yes yes. But. He was also Paul Gauguin. Is it “ok” is a moral question. I’m less interested in that question. A much more intriguing line of enquiry, I think, is: Did he contribute something crucial to modern Art?

That answer is obvious. To me, anyway.

A little conflicted about this one because I feel like we automatically give a pass to anyone claiming to be an artist, regardless of their contribution to society or posterity. And this gives any and every asshole license (reward, even) to be narcissistic, irresponsible, ridiculous, debauched, or whatever. Are these things essential to making good art? I don't think so. I doubt they're even helpful. (And I'd argue a lot of this art is dogshit, but hey, opinions are subjective.)

Artists are perfectly capable of making art while also maintaining some semblance of self-control. Indeed, it's the only way anything worthwhile gets done! It's the myth that art (or genius) and chaos/darkness coincide that we perpetuate that removes whatever moral and practical constraints would normally keep pricks like this in check. He was perfectly capable of holding down a job and keeping up his obligations to his family until he started hanging out with other artist reprobates, and like a plague, the contagion of artistic assholery spread to him and he became a boil on the ass of society like the rest. If a rock star doesn't trash a hotel room, bang a bunch of groupies, or get high before the show, is the music somehow diminished? or is it all baked into the image artists project to us and to each other to prove their "creative" bona fides? At the very least, it's a lesson in what happens when the wider society removes its social constraints from already morally weak individuals.

What's that old saying?? learn to "separate the art from the artist" which seems quite applicable to Gauguin (who btw I had never heard of until now. Great read)