Random Thoughts

Russian Authors, the Human Condition, Style Versus Story

Like my writing? Here are some ways to support me:

1. Re-stack this post

2. Share with friends and family

3. Subscribe for free, or paid $5/month; $35/year; $200 Founder

4. Buy my literary YA novel HERE ($3.99 eBook) and review it on Amazon (the book is available everywhere now: Ingram Spark, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop.org, etc etc)

5. Like/comment

~

His sensibility was to eavesdrop, to hear and see everything around him and to record it, and to record every single sensation and emotion within himself and, to whatever extent possible, within others. Dostoevsky wanted to genuinely understand The Human Condition, to crack open the sacred fruit that is the human heart, to look inside of a human soul and see what lie at the core.

~

I’m currently reading multiple books—as so many of us writers do—but two are: “The Gift” which was Vladimir Nabokov’s final Russian novel, written as an ex-pat living in Berlin between 1935-1937, though not published in English until 1961; and “The Diary of a Writer,” nonfiction selections of diaries and articles between 1873 and 1880 by Dostoevsky.

I’ve always been fascinated by the Russian literary masters: Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Gogol, Chekhov, Nabokov and many others. I first encountered the importance of Russian lit when, as a child and picking through my mother’s massive musty old collection of classics, I randomly picked up “Dr. Zhivago” by Boris Pasternak. And then again it happened, more meaningfully, in my early twenties when reading Hemingway’s brilliant, sassy memoir, “A Moveable Feast,” about his 1920s Paris years as a young man trying to make it as a writer living with a wife and kid. In the book Hemingway mentions his love of the older Russian 19th century masters. This led me to explore.

There’s something doubly intriguing and provocative about comparing Nabokov—author of “Lolita” and the memoir, “Speak, Memory,” born in 1899—and the great, inimitable, genius Dostoevsky, perhaps the most important author of all time, at least in the “modern” world, born in 1821 and author of such classics as “Crime and Punishment” and “The Brothers Karamazov.”

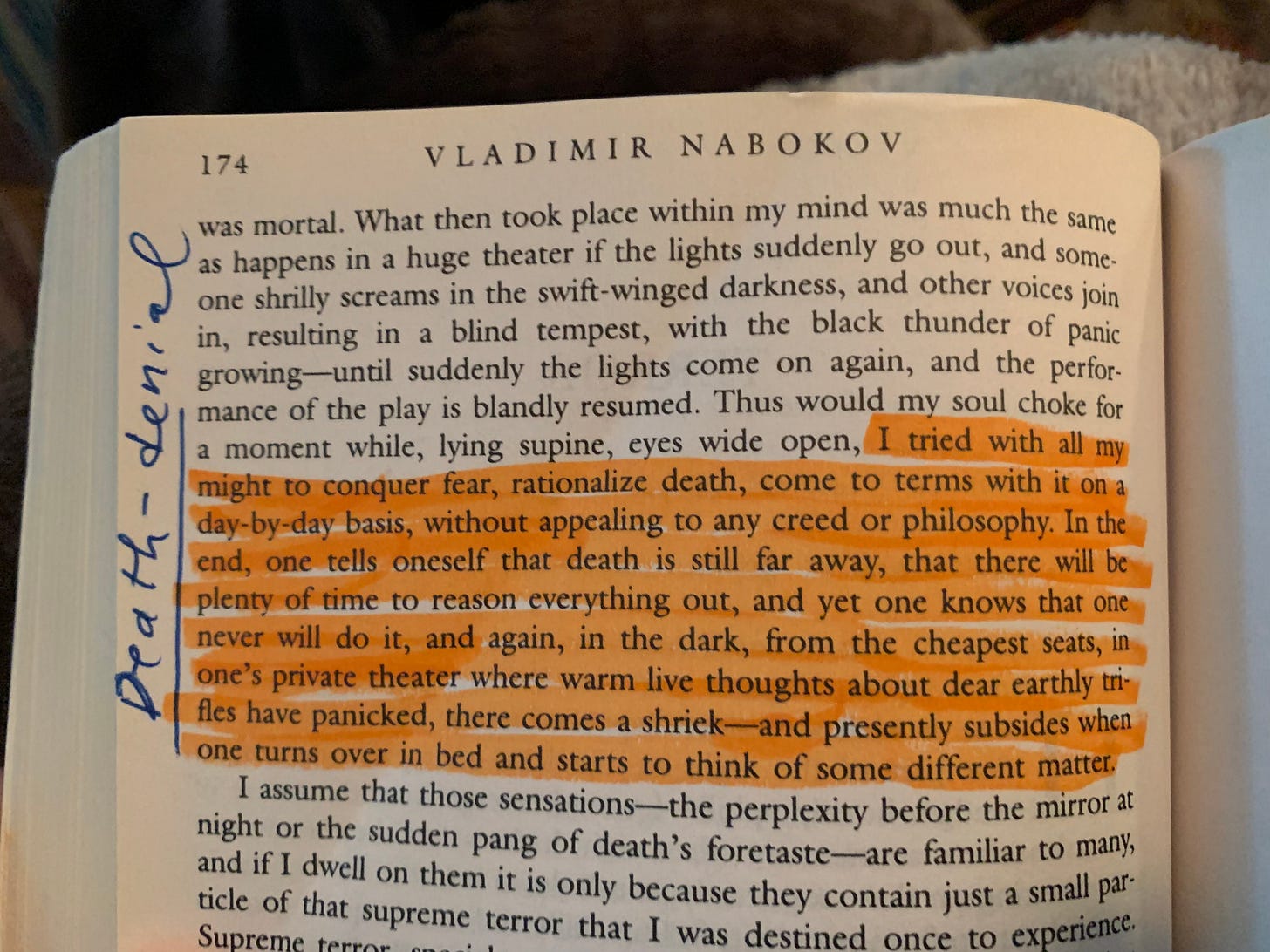

There are many differences between the two writers who were born 78 years apart. Nabokov was a wonderful stylist for one thing, a writer who enjoyed squeezing the very last bit of literary juice from each and every word, sentence, paragraph, page. He was in love with language, with cadence, with the sacrosanct act of literary baptism. His novels hit home in general less because of plot and more because of, yes, character, but, even more than that: A sort of poetry, taken non-literally. (Though there were actual poems, too.) Some of Nabokov’s lines are pure as gold, woven by fine, rich hands and a fine, rich imagination, not so much written as dripped slowly from his soul.

Dostoevsky, by contrast, was not so much of a wordsmith, not so much of a man obsessed with language so much as an author obsessed with story, plot, character, human tragedy, deep introspection, the search for love and hate, good and evil, right and wrong. His sensibility was to eavesdrop, to hear and see everything around him and to record it, and to record every single sensation and emotion within himself and, to whatever extent possible, within others. Dostoevsky wanted to genuinely understand The Human Condition, to crack open the sacred fruit that is the human heart, to look inside of a human soul and see what lie at the core.

Nabokov was surely interested in many of these things, too, of course, but as I said: His foremost obsession and concern was with making words and sentences dance dangerously on the page like sweating, absurd professionals on the dancefloor of the human experience.

Nabokov penned lines like, “What if we could return to the past carrying the contraband of the present?” (The Gift)

or:

“The cradle rocks above an abyss, and commonsense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.” (Speak, Memory)

Both authors tended to get lost in emotional, interior and philosophical asides in their work, Dostoevsky sometimes veering off the main path for a dozen pages or more. They were bonded to the creative notion of going deeply into a character’s psyche, tending to that solemn and joyful and complex inner garden. Complex, contradictory unconscious and conscious drives and desires moved the people they created on the page. Dostoevsky, sometimes referred to as the “first true psychologist,” wrote frequently throughout his life (1821-1881) about the “unconscious,” long before Freud (born 1856).

Dostoevsky, it has always seemed to me, comes into any piece of writing—fiction or non—with sincere curiosity, hoping to uncover some gems while simultaneously enlightening his readers. Whereas with Nabokov, you always feel as if a Literary Father is sweetly singing you a bedtime song, the lights out, the voice low and deep, and you with eyes closed, grinning in the darkness. His voice, language and tone are steeply authoritative. Having read a thick collection of Nabokov’s letters, I can tell you the man had profound artistic integrity and didn’t take anybody’s bullshit, and that includes editors, publishers, magazines, film companies, close friends, enemies, you name it. He’d rather lose a lot of money than have his perfect prose clipped badly by some wanton editor, even if only a few lines. He was stylist and also a staunch perfectionist, probably both a help and a hindrance to both the man and his work.

But Dostoevsky was in many ways a “man’s man.” (What is a man, anyway?) Though technically of the “nobility,” of the bourgeois middle-class, he suffered. His mother died when he was only 16. Dad died—was in fact murdered by his own angry peasants—when Dostoevsky was only 18. In 1849—still at the tender age of 28—the author was arrested with many others, entangled unlikely in the socialist Petrashevsky Circle, a secret socialist club. Czar Nicholas I had been terrified due to the revolutionary uprisings across Europe in 1848, coincidently the same year Marx and Engles’s “The Communist Manifesto” came out. (Marx and Dostoevsky were contemporaries.)

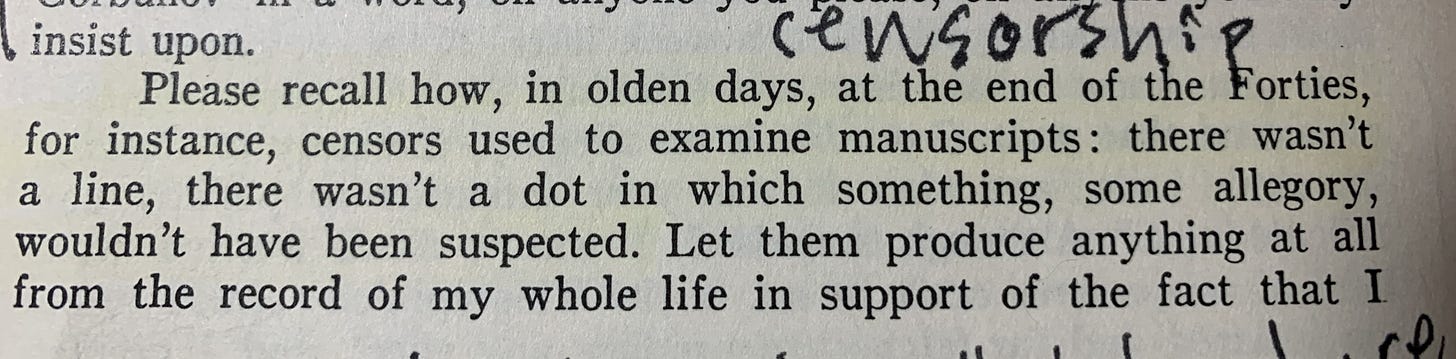

This led to four long, tough years of “forced labor,” aka ruthless prison, followed by several years (required) in the Russian military. It took several years even after his release before he was able to return to his beloved and literary St. Petersburg. But his prison notoriety helped his writing career: He published, in 1861, his profound prison memoir (called a “novel” with details adjusted to get past the censors of the time), “Notes of a Dead House.” This book rocketed him to a new level of fame and respect. He’d even had to undergo a fake firing squad when first sentenced to death in 1849, placed up against a wall with men holding rifles aimed at him. He accepted his death and wrote before this moment to his brother, Michael, saying he’d had a good life. But at the very last second the sentence was commuted and he was instead sent to hard labor in Siberia. This was a planned event…but Dostoevsky did not know this until many years later.

Nabokov, on the contrary, lived a life of profound wealth, privilege and leisure, as described in his memoir, “Speak, Memory.” Still: His family fled Russia during the Bolshevik Revolution, when Nabokov was just 18. This became the beginning of his ex-pat years, living in Berlin, Paris, Switzerland and later the United States. He remained all his long life a hardcore anti-communist, though he never fell into the extremist trap of someone like, say, Ayn Rand. He wrote books and novels and poetry, obsessed over butterflies, and lectured at universities. He was a refined man, an aesthete of the highest degree, a pedigreed author, a quintessential literary writer, a man who did not try to be tough physically and yet who also had a deep love of boxing, like Hemingway (born the same year, 1899).

Both authors tended to shift away from the realism offered early by Flaubert (who had almost the exact same lifespan as Dostoevsky, 1821-80) in France and Theodore Dreiser (born later, in 1871) in the States. Instead they opted for the depth of imagination, the rich color of language, the tuning of plot and storytelling, the sensing into the inner landscapes of the tortured and innocent psyche of man, the explorations into the stormy and maladaptive mind of human beings filled to the brim with complexity, contradictions, ego, fear, love, joy and terror. They asked the question, “What if?” They left the answers dangling for readers. Their were conclusions offered but never any deep answer to any one proposition. Instead, they both worked towards the mysterious, the dark unknown, the hazy and misty and mystical, the closed and quivering that is all of us, within and without.

Without the Russians I’m not sure what the direction of literature would have been. The Russian masters seemed to know something the rest of us didn’t, at least not in Europe and America. Perhaps it was because of the Russians’ profound suffering during the 19th and 20th centuries, moving from the repressive czars, indentured servitude, banishment to Siberia for almost any offence, to the grotesquerie of Lenin’s Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, leading eventually to the tragic horrors of Joseph Stalin and his incredibly long list of murdered, disappeared citizens between 1929 and 1953. These writers hit closest to the bone of the human experience perhaps because they never had a chance; unlike many parts of Europe and the States they did not taste true freedom, and in many ways they still haven’t. (From the Revolution to the Cold War to Putin.)

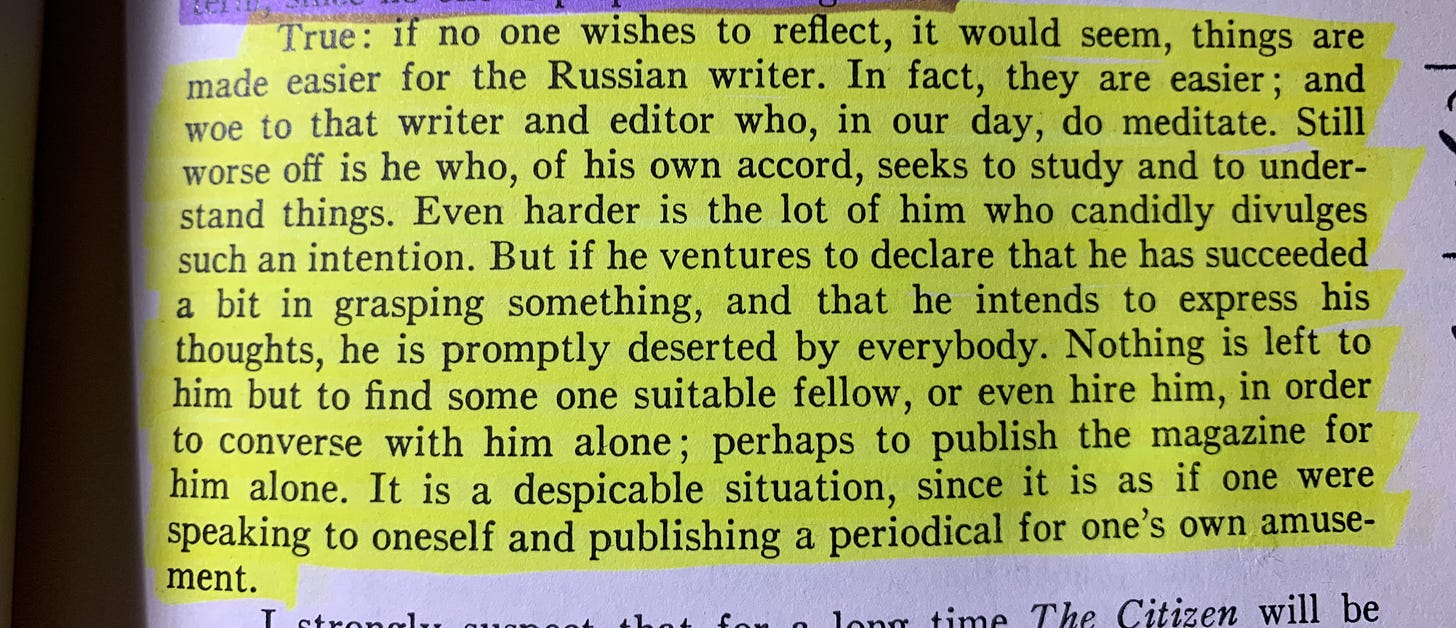

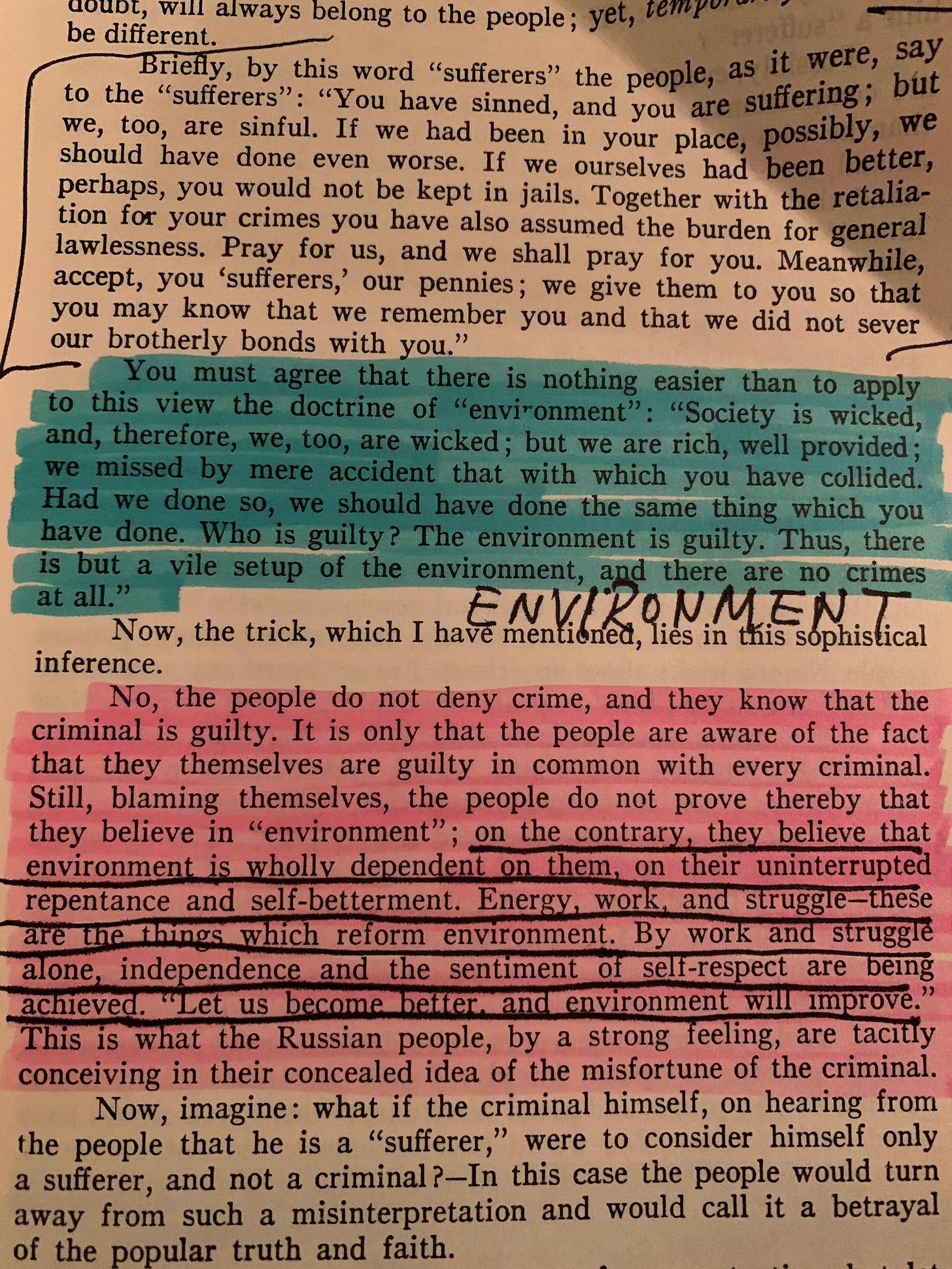

We are free and thus can complain about things which perhaps aren’t always fully steeped in reality. The Russians, it seems, never had that leisure, that indolent opportunity. Instead, they had to tell the truth and do it ruthlessly, while, at the same time, in the 19th and 20th centuries, under the tyranny of both the czars and Lenin/Stalin, telling their profound truths in slanted ways, simply to bypass the repressive censors.

Both of these authors—Dostoevsky and Nabokov—told the truth in their time as they genuinely understood it, according to their own biases, their own environments, their own contemplative notions of peace, justice, love and change. Were they right about everything? Of course not. No individual from any time ever is. But they managed to fulfil the requirements of true literature: They asked big questions and provided universal consciousness within creative terms to get as close as they felt they could to something resembling Truth.

That, I think, is all any of us can really do.

A great reminder to read or reread the Russian classics. Not original to me, but sometimes I agree with the thought that perhaps out of great pain comes great art? (We know the Russians to have great lit, opera, ballet.) But from that part of the world comes one of my fav poets who often asked himself what was his role as a poet. Was it to record/be a witness of life around him? Be that human "witness"? Here is an except from his poem "In Warsaw": I hear voices, see smiles. I cannot/Write anything; five hands/Seize my pen and order me to write/The story of their lives and deaths./Was I born to become/a ritual mourner?/I want to sing of festivities,/The greenwood into which Shakespeare/Often took me. Leave/To poets a moment of happiness,/Otherwise your world will perish. Czeshalw Milosz, Polish.

Very interesting examination. I wonder how contemporary Russian literature compares to their classical counterparts? Do you know if modern life has "dumbed down" their writing as has ours? Not just in terms of components of writing (vocab/reading comprehension/ etc.) but in their exploration of understanding man's nature and relationship to himself and the world?