Sally Rooney: Queen of the Millennial Novel?

Rooney’s New Novel, INTERMEZZO; Anti-Israel Feelings; Marxism

I bought Intermezzo, I confess, as what I called a “hate-read.” Just buying a book by a contemporary author as liked and famous as her was in and of itself enough for me to mock and loathe her. Add to that her “Marxist” beliefs, and then her anti-Israel views and, well, you can see where I’m going. I fully expected to find a book chock-full of identity politics, flattened 2-D characters, wokeism-galore, bad dialogue, weak MFA program fiction, etc.

But that is not what I found. Not by a country mile.

~

This is going to be a controversial essay for one simple reason: I’m supposed to pick sides.

For those of you who don’t know who Sally Rooney is: Here’s the very basic scoop. She’s 33, Irish (from Castlebar, County Mayo in Northwest Ireland), has published four novels, including Normal People and the brand-new 2024 novel Intermezzo, is an avowed Marxist, identifies as a feminist, has become increasingly famous (at least within the literary world), and has, to varying degrees since the fall of 2021 (and more so recently) criticized Israel in their treatment of Palestinians even going so far as to join the BDS (Boycott, Divest, Sanction) movement and disallow Israeli publishers from releasing her work or translating her books into Hebrew.

Because of this, I’m supposed to hate her, reject her out of hand, and certainly never buy or read her work. Especially me, of all people, right, given all my ranting about progressive extremism over the past few years?

But here’s the thing: I’m an independent, contrarian free-thinker. I loathe both political sides at this point. I may be “anti-Woke” but I’m just as much “anti-ANTI-Woke.” Extremism and polarity and superlatives tend to suck all the air out of the room. Extremism leaves no room for the nuanced messy humanness which is where all of us actually live.

I also strongly believe in the sacredness of separating the art from the artist. Yes, even when it comes to boycotting Israel, refusing to allow Israeli publishers to release her work, not allowing her books to be translated into Hebrew, calling what Israel is doing in Gaza a “genocide.”

Knut Hamsun was a brilliant author (he wrote Hunger and Growth of the Soil); Hamsun won the Nobel Prize for Literature: He was also a Nazi supporter and met personally with Hitler, proclaiming the man a hero and savior. John Steinbeck was brilliant; I loved East of Eden, The Grapes of Wrath and many more of his books: He also was a huge, passionate supporter of the Vietnam War. Celine (who’s profound World War I novel I read during COVID, Journey to the End of the Night) was a rabid antisemite. Norman Mailer was, when younger, an angry, alcoholic, violent socialist-Marxist who stabbed his wife, Adele, in 1960. Henry Miller, Charles Bukowski, Kerouac and many others had their bad moments with women. Hell, if you want to really get down to it: Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence, owned slaves.

Yet all of these authors were brilliant and absolutely required reading.

Wouldn’t I be the wormiest of hypocrites if I said, Well, I know I defended all those 20th century male authors, defending their rights as artists, using the ‘separation of art and artist’ framework, but, you know, it doesn’t really apply to contemporary women authors who I politically disagree with?

Yes. I would.

As many of you know I have been very vocally pro-Israel. Read my essay on this here. I’ve also been vocally against identity politics of any kind, from either/any side. And I’ve been highly critical of Democrats the past decade. (I also hate Trump and think the Republican Party has largely become an absurdist joke.)

Without hesitation I will say that I strongly disagree with Rooney when it comes to her stance on Israel, the BDS movement, refusing Israeli publishers from putting her work out, blocking Hebrew translations. I have no doubt people in Israel feel this as a literary and cultural slap to the face, and I don’t blame them.

And yet: When it comes to an artist’s work I want to be able to stand above all of that and freely judge the work by its own merits. I knew about the buzz around Rooney and her career and her books. Around 2021 I read Normal People and was not much impressed. That book had received a lot of industry attention and, somewhat similar to my take on Emma Cline’s The Girls in 2016, I thought it was overhyped. (Cline’s book was better.) Normal People was a decent novel but it didn’t feel in any way revelatory or incandescent to me. I also saw Rooney speak at McNally-Jackson Books on Prince Street in SoHo, NYC, circa 2017. I found her comments on Marxism at the time to be, to say the least, immature and unformed.

Honestly, I wasn’t even planning on buying Sally Rooney. As a combination Christmas/Birthday gift I’d received $200 in gift cards for Portland’s wonderful Powell’s Books. So, one day I walked into the Powell’s on Hawthorne with the intention of buying Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations, which I’d been listening to on Audible and been so fascinated by that I wanted a physical copy because I wanted to highlight, write marginalia and screenshot quotes for Substack Notes.

But, when I walked in I saw Rooney’s bright yellow chessboard cover, SALLY ROONEY in thick black at the top, INTERMEZZO in same at the bottom, I had a realization which has been brewing inside me for a while now: I don’t read enough women writers. More than that: Generally speaking, I don’t read enough contemporary writers, period.

Too often I’ve been slightly stuck in my own ignorance on this score because of my dislike of Wokeism, my dislike of Fourth-Wave Feminism (being often highly anti-men) and my dislike of the handful of contemporary novels I’ve read over the past decade. There were exceptions: Anything by Zadie Smith I loved. Everything by Ottessa Moshfegh; read my recent essay on her 2022 novel LAPVONA here. Stephanie Danler’s Sweetbitter I liked. Emma Cline’s The Girls.

But mostly I’ve always generally read 19th and 20th century classics by dead white men, as the youngsters say now. Dostoevsky. Tolstoy. Nabokov. Roth. Bellow. Hemingway. Miller. Bukowski. Mailer. Etc. You get the idea. It has always felt to me like writers before say the 1970s—when a lot of people still read books, New York was still the mecca of publishing, dissenting opinions and views were allowed and normal, and artists could say more or less whatever the hell they wanted—were the “real writers.” They weren’t inhibited by strict social structures from above and below telling them to pick a side or have fill-in-the-blank ideology. Actually, that’s not true: They were told this but it was okay if they rejected it. It was a time when art was pure. One could be an artist without an agenda.

I still think in many ways that this is true; that writers of 50, 100 years ago were much more “authentic” in many ways, living in a time before radical politics exerted such forceful pressure, before iPhones and social media had both connected and disconnected us all so powerfully on a global level, before the intense conformism of Millennials and Gen Z produced generations of kids who couldn’t think independently or focus on something for more than five minutes at a time.

And yet.

I bought Intermezzo, I confess, as what I called a “hate-read.” Just buying a book by a contemporary author as liked and famous as her was in and of itself enough for me to mock and loathe her. Add to that her “Marxist” beliefs, and then her anti-Israel views and, well, you can see where I’m going. I fully expected to find a book chock-full of identity politics, flattened 2-D characters, wokeism-galore, bad dialogue, weak MFA program fiction, etc.

But that is not what I found. Not by a country mile.

~

The Book

Intermezzo means basically an intermission of sorts. A light instrumental between acts of a play, or a short musical movement introduced between sections in an opera, etc. A go-between, as it were, between two parts of a play, dramatic work, opera, etc.

The novel follows two brothers, Ivan (22) and Peter (32). They are not close but once were when much younger. Peter is a hardworking “rich” attorney (and leftist) and Ivan is a chess-master who does data-analysis on the side and lightly explores the outer circles of anti-feminist incel worlds.

But the book is, more than anything else, the story of these two brothers and how they find themselves back in each other’s lives.

Rooney loves exploring power dynamics. And she loves nuanced complications added to those dynamics. Ivan falls in love with an older woman who’s 36. Peter falls for a 23-year-old who starts out as his “sugar-baby.” (She sleeps with him and he covers her financially. The classic “sugar-daddy.”)

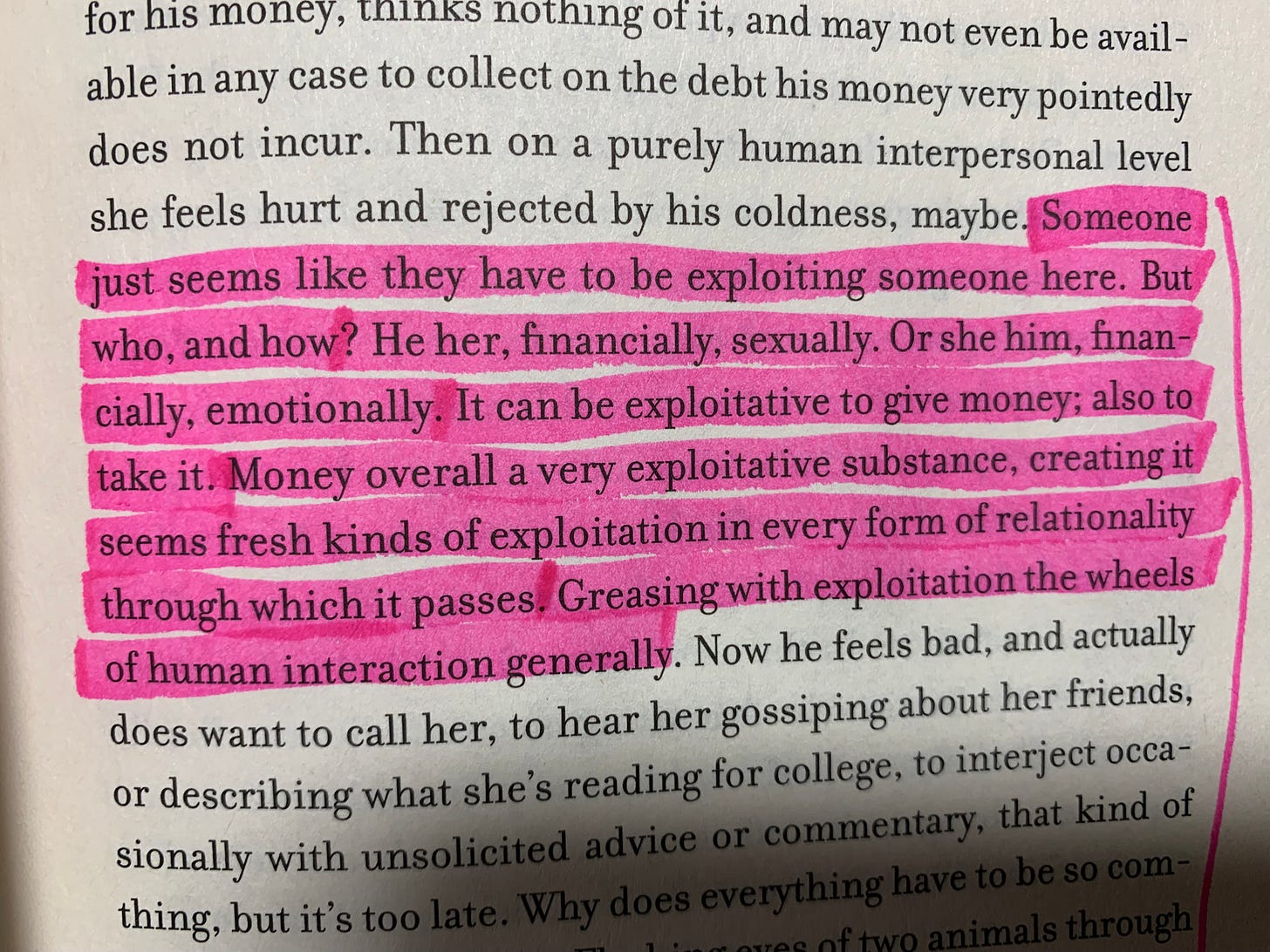

The question on both sides becomes: Who exactly is using who? Who has power over whom? Rooney, delightfully, as any good novelist does, doesn’t attempt to answer this question. Instead, she poses subtle and profound questions. Perhaps the 36-year-old woman, Margaret, is taking advantage of the pure, innocent, naïve 22-year-old Ivan? Or, is the 22-year-old Ivan in a sense taking advantage of the wounded, broken emotional neediness and lostness of the older woman? With Peter: Do we have an older man taking advantage of a younger woman? Or, does this younger woman (Naomi) know exactly what she’s doing and, by using sex and her body, is she taking the older man for a ride, using him for a place to crash and money in her account while pretending to love him?

Or maybe it’s all of the above, simultaneously?

You have to ultimately draw your own conclusions here. And perhaps there aren’t any easy, binary answers. One thing is crystal clear to me, though, after reading the 450-page book: Her characters are deeply drawn, three-dimensional, rich, with true depth and scale and authenticity. I could see pieces of myself in all her characters, but if I’m being honest I see myself most in the arrogant, intelligent, witty Peter, the man terrified of love, afraid of vulnerability, obsessed with being perceived a certain way. (At least my old pre-sober self. Now I suppose I’m more of a mix of Ivan, Peter and Margaret.)

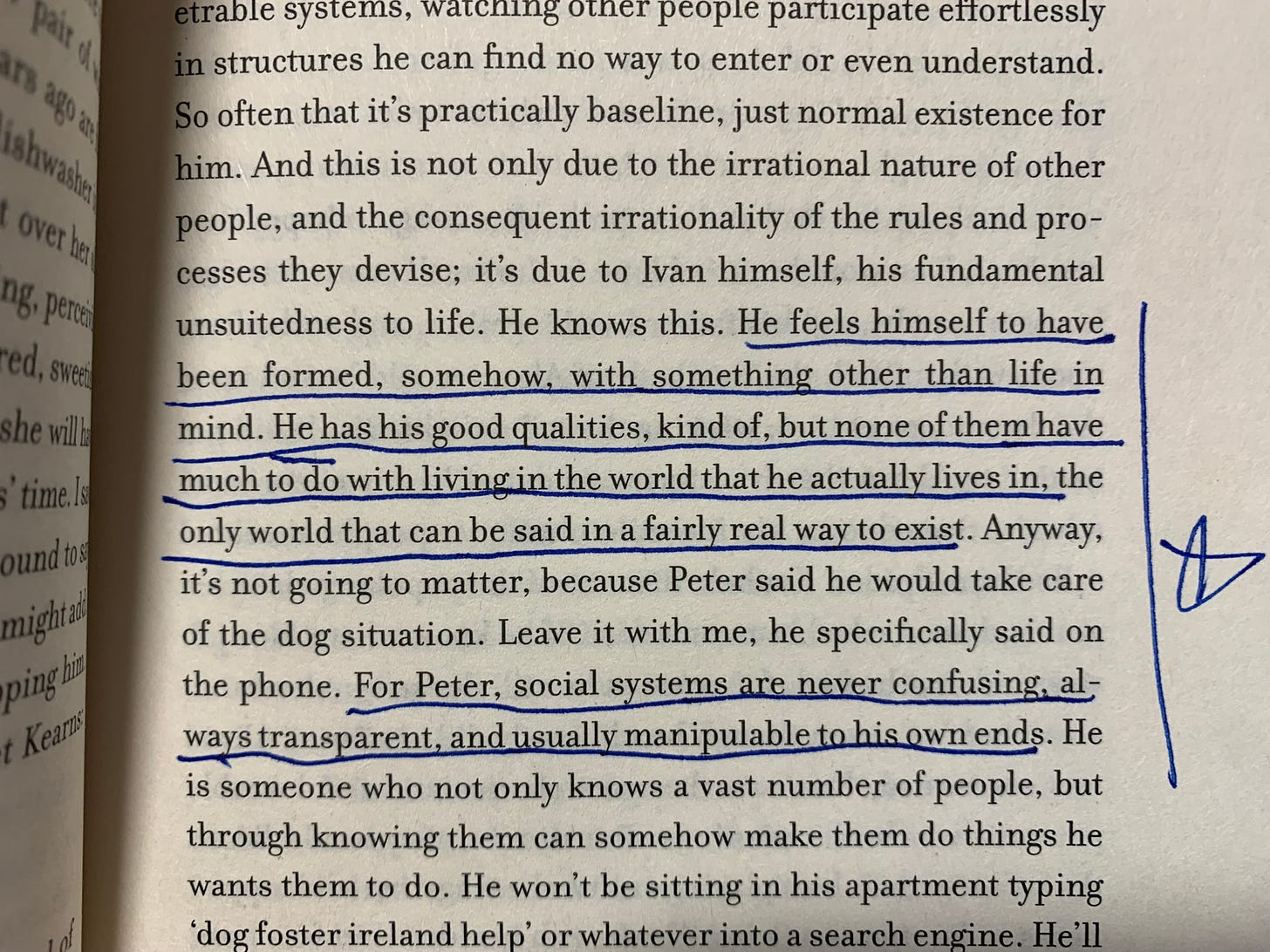

First we should acknowledge that Rooney is a woman, and yet she wrote from the point of view of two men. The novel is written in 3rd person omniscient, active voice, so she dips into everyone’s POV, almost, definitely the brothers and Margaret as well as Naomi. But the brothers’ POV are central. How do her male characters hold up? Pretty well, in my view. At first I felt that Ivan, the pseudo-Autistic chess genius, was a little too “feminine,” a little too soft. But over time I began to believe him. I realized there are guys like this out there; nerds, chess-geeks, videogame players, those kinds of quiet, polite, thin, pimply people.

Peter, who as I said I relate to much more, is a lot angrier, more arrogant, more sure of himself, confident, with violence in his mind and in his reflexes. He’s more traditionally masculine, even while being a hardcore lefty in his politics. (She doesn’t describe his politics much; it just hovers gingerly in the background.)

Both men are, like most of us—certainly me—hypocrites, full of contradictions. Peter judges Ivan harshly for seeing an older woman, all the while surreptitiously seeing a 23-year-old girl behind closed doors. Ivan thinks of Peter as being an arrogant asshole…even as Ivan himself sometimes acts like an immature, childish, arrogant asshole.

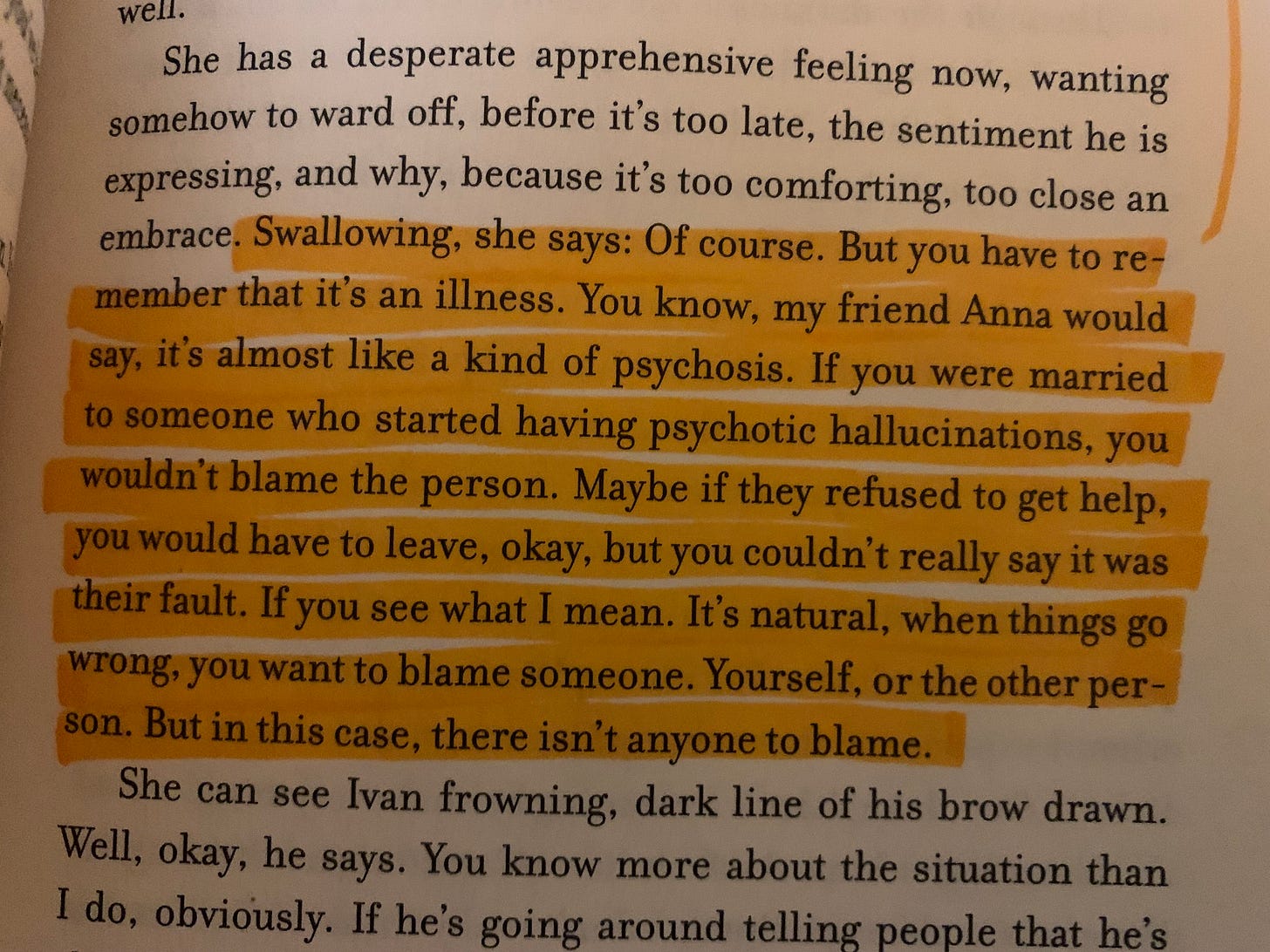

The women seem to fulfil the deep emotional roles in the book. Margaret helps Ivan achieve more openness and vulnerability, and Naomi does this with Peter. Both men struggle on their own to truly feel their feelings, to see themselves in their truest, stripped form. The women, however, are better at this. And this feels, in general, to be true to life.

I myself have always been highly sensitive, highly self-aware, highly in touch with my emotions…and yet, even I know that, despite this (a contradiction) I often can’t handle vulnerability and I often run away from feeling all my feelings. Men are hardwired that way and aren’t encouraged by society (Rooney would say by our “system,” probably) to face these things.

Each character feels very unique and individual. They all want different things and are often at direct cross-purposes from each other.

If comparing to other books I’d say generally that Intermezzo feels like a strange mix of Bret Easton Ellis’s Less Than Zero mixed with Jonathan Franzen’s sprawling relationship drama, Freedom.

Another major plot point which I purposefully didn’t mention until now, because, even though it hovers behind and below and around everything in the novel it somehow doesn’t feel like The Main Thing: The brothers’ father has just recently died when the novel opens. Neither seems to be able to feel the pain of this reality. In fact, neither seems to fully accept the reality that their dad is dead and gone, at least not for most of the novel. Could all their searching for love, sex, women, be part of the conspiracy of distraction that is contemporary culture? Peter is a pill-addict and alcoholic who struggles with suicidal ideation. Ivan is not like this but also struggles with feelings of meaninglessness and lack of purpose.

The complexity of the family dynamic is explored throughout the book: Not just the brothers with each other but their mother (who left when they were young and who neither of them care for much), their father’s void/absence, the women they pursue and those women’s families as well. Their lives are all tangled and inextricable, full of unmet expectations, disappointments, hypocritical ironies, the search for deeper meaning, love lost and possibly regained, etc. Of course the notion of The Age Gap is explored with both brothers.

Themes of meaning, redemption, sexual/love games, seeking external validation in order to feel whole and worthy, wanting to be saved by someone, the concept of desire, and much more are rich in the novel.

This is where the chess metaphor comes in. Intermezzo, the title, too. Peter and Naomi, Ivan and Margaret are all experiencing each other in a sort of break, a light musical intermission between the different acts or moments or periods of their lives. There is no resolution by the end in terms of what happens to these relationships; there is no neatly tied-up bow. But we assume that Peter and Naomi (and there’s a whole side-plot with Peter’s ex-girlfriend, Sylvia) as well as Ivan and Margaret will be together for a while and then, facing the hard walls of reality, will sooner or later split apart and go their own ways. Ivan fervently rejects this notion when the older, wiser Margaret talks about it multiple times…but he is 22; he doesn’t yet know what he doesn’t know. Only life experience brings this awakening knowledge.

Life, or rather relationships—platonic and romantic—are very much like a chess-game for better and worse. We sit across the board of life from each other, watch one another, and make our moves, hoping for the best. One doesn’t always necessarily “win” and another “lose,” but there’s always a point at which the game ends, and a new player is found. And this I found true as well. Love and sex and romantic relationships do often feel like games, deep conscious and unconscious psychological games wherein each person is making assumptions about what the other wants, thinks, hates fears, and wherein each person is trying to outwit the other, trying to outsmart the other, trying to anticipate, to read their eyes and hands and fingers and moves ahead, trying to understand and mathematically unpack what the other person might do, and why.

But of course this game is all played via the mind, via dialogue, via actions. None of us can ever know absolutely 100% for sure what kind of game we’re playing, or even if we are for certain playing any game at all. But most of the time almost certainly some sort of game is being played. Anytime two people are engaged with each other games will occur because we can never fully, completely merge minds. And each human being has their own needs, wants, desires, fears, regrets, defense mechanisms, etc.

Rooney explores all of these subtle dynamics expertly. She slowly, carefully peels away the layers of the onion within her characters’ inner worlds. She is startlingly powerful with dialogue, and this, like many contemporary novels, is a very dialogue-heavy novel. She uses the trick of indentation and capitalization instead of using any quotation marks. Like Cormac McCarthy and Paul Auster and others. I didn’t care about that one way or another. But the dialogue is strong, crisp, tight, and very authentic. It always moves the story forward. She’s really good at introducing an action scene, then getting into sticky, hooky, delicious backstory, and finally delivering us back to the present scene. She sets things up wonderfully.

There are some annoying things, for sure. Rooney has a bad habit of sometimes here and there, for a paragraph or two usually, interjecting silly, bad politics, usually of a “Marxist” or anti-capitalist nature. I hope as she matures as a writer she leaves this habit behind. In the video posted above she said her work is never ideological. In spirit I agree with this, at least as pertains to Intermezzo. Except for those half a dozen interjections which seem to have no impact on the story and could easily be deleted.

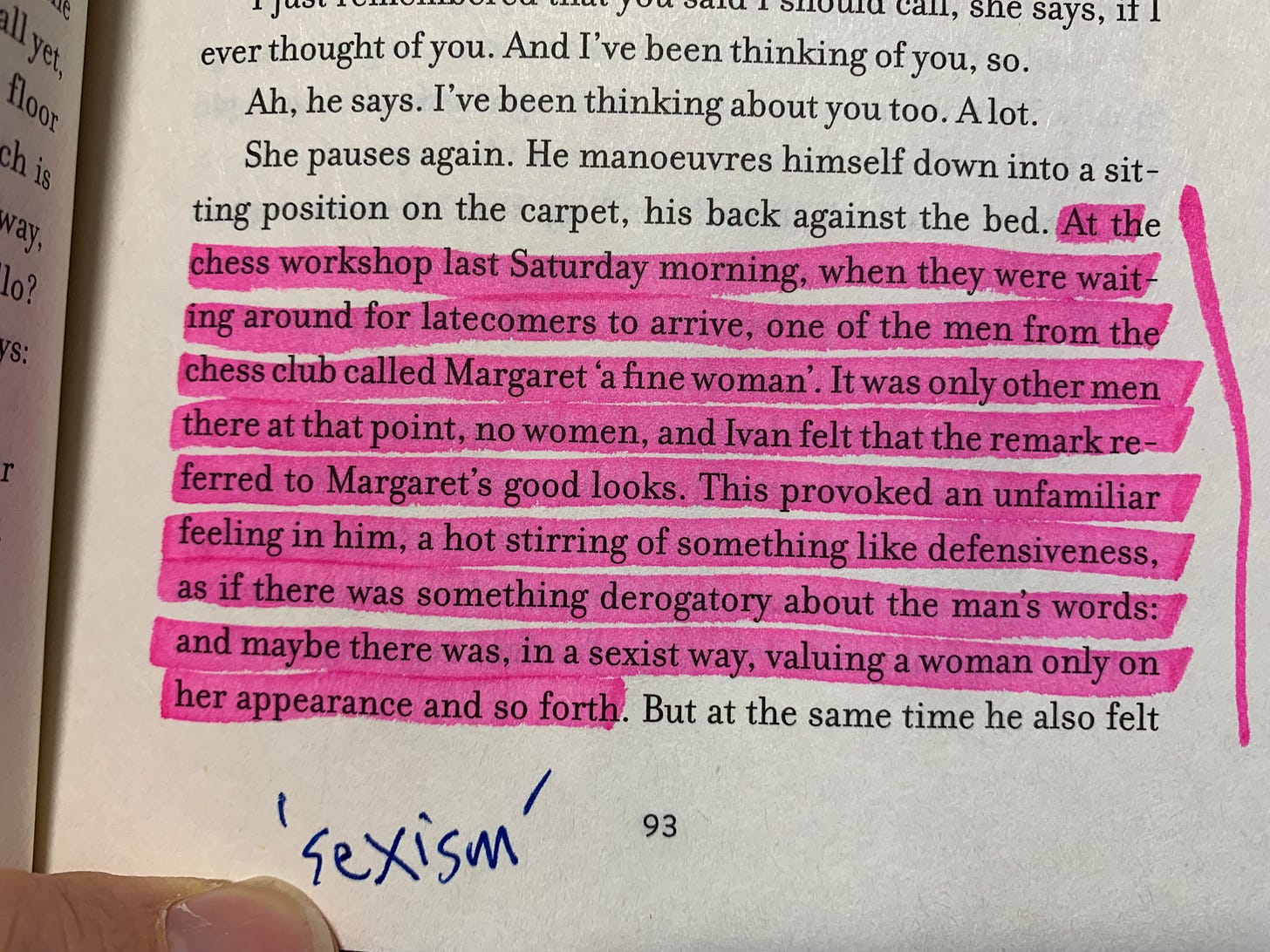

Sometimes assumptions are made about the male characters which felt a little exaggerated, unfair or over the top, like when Ivan complains about having to give us his seat on the train to pregnant women, thinking this is unfair. I have never in my life met any man, young or old, who felt giving up their seat on a train to a pregnant woman was some form of male “oppression.” C’mon.

Sometimes the writing—particularly in the early chapters—felt a little too choppy and overly clipped and polished, too “MFA-ish” to me. Especially Chapter 1, which was from Ivan’s point of view. This was clearly done on purpose to demonstrate his erratic, choppy personality. I get it. Fine. But I started to feel seasick. Too choppy for me. But it did, after a couple chapters, soften up; the sentences grew longer and softer, easier to read.

Like Emma Cline’s The Girls, this novel “teaches you” how to read it. The point of view is very, very direct and deep: We’re right in the characters’ heads, deep as you can go. As readers we inhabit the characters’ minds and bodies completely, walk around in their skinsuits on the page.

It's a slow-moving novel until it starts moving. By page 70 I nearly stopped reading and gave up. I’m glad I didn’t. Rooney uses a lot of dialogue it’s true, and there is the perfect mesh of plot and character-driven story, but she also uses a lot of backstory, context, expository information. This means the first say 20% of the novel is rather slow. But it picks up a little as you go, and by the time you’re 150 pages in you’re so invested in the characters and the story that you feel like you’re moving 90 MPH along I-5. Rooney makes us care about the people she creates. She grafts our lives onto them.

Is Rooney a good person in real life? I don’t know. Probably. Do I think she’s evil for what she’s doing re Israel and her work? No. I think she’s more than anything young, uninformed, psychologically captured by her own generational ideology and has taken a stand about something she likely doesn’t fully understand on the fullest level.

Do I think she’s the voice of her (the) Millennial Generation? No. I think she’s a potent author with pros and cons as a human and as a writer. I think she nailed down certain aspects of human complexity in our time, the third decade of the 21st century. Rooney is flawed just like her characters, just like all of us. I don’t defend her as a woman, a person; I do defend this specific novel, because I think it does what a novel should do: Tell the truth of your time and place.

On the YouTube video interview (New York Times) of Rooney at the top of my post—and I recommend you listen to it—from October, 2024, she sounds incredibly sincere to me. Clearly, she hasn’t prepared polished answers and hasn’t seen the questions before the interview. She pauses a lot, repeats herself, stumbles, and takes time to answer as honestly as she can.

And really: She sounds incredibly reasonable. She says she has never read a single author biography. She says she sees things through a “Marxist” lens. She says she tries not to inject ideology into her novels, and to the extent that she does on a minor level, it doesn’t affect the characters in any meaningful way. She says that people are complex and nuanced. She says that she lives a pretty boring life other than writing. She says she’s incredibly grateful to be alive. She says she feels most alive while in the throes of writing. She’s deep, intense and sounds like someone I’d probably get along with.

She even admits that her being a young white woman likely helped her get published and even famous. (Yet also discussed the inherent sexism she’s had to endure.)

She even says she’s a huge fan of Dostoevsky. As I am.

Except for her politics, of course. That part of her, for me, is dreadful.

But so are a lot of people for me. A lot of writers, especially in our times now.

Don’t take my word for any of this. Go out and buy Intermezzo and find out for yourself. It’s not the greatest book of our generation. No way. And it’s almost certainly not going to be a classic that people read and discuss in 100 years (if literature is even discussed at all by then). It’s not without its weaknesses and problems, stylistically, even structurally at certain points.

Rooney is a good storyteller. The voice is strong, the language is simple, the style (after the first couple chapters) is easy. The sexual tension is magnificent; it keeps you reading the pages just to see how it unfolds. She writes very realistically about the rabid, almost bipolar ups and downs of human emotions, how you can be way up one moment, down in purgatory the next. Her physical settings and details and use of the five senses is often delicious; she can make even a brown stiff fall leave scratching along the sidewalk feel real. The dissonance between what a character thinks/desires/wants and what they say/do is very palpable.

One of the major themes is, of course, desire. We all desire what we can’t have. Or we get what we think we want and we realize we don’t actually want it. The grass is always greener. Things will always be better when we get…fill-in-the-blank. The novel is also about grief, secrets, lies, and surviving one’s own unmet (often unrealistic) expectations. The spiritual impossibility of true love, true connection, true understanding. Forgiveness, letting go, accepting things as they actually are—not as we want them to be—and accepting other people as they are: These are more core themes. The notion of “normality” versus being unconventional. Being an insider versus being an outsider. (Aren’t we all on some level both normal and not normal, conventional and not conventional?)

The novel is about emotional assumptions, how we so often assume we know who someone is, why they did what they did or said what they said. We’re often, of course, dead wrong. (Even about our own actions/words/motivations.)

In the end the two women, younger and older, ultimately bring the two brothers back to each other, where the idea of redemption is finally possible.

Intermezzo is a damn fine work of art. I stand by that a hundred percent.