Saul Bellow

There is Simply Too Much to Think About: Saul Bellow’s 2015 nonfiction Collection

Saul Bellow—Eastern Canada-born, Chicago-raised, NYC-living, Paris-living Jewish author who lived from 1915-2005—has captured my imagination as of late. Some of you are surely aware of this. My last S.A.W. post—that is, Sincere American Writing—had the cover of Bellow’s book as the main photo and included quotes from the book. Additionally, I have been more or less obsessively posting fragments of genius lines from the work on Substack Notes.

Because I was so fervently interested—still—in the author and the book, I decided to do a second, and more in-depth, post on it/him.

Let me say right off the bat that I am far from being a well-read Bellowian. Besides this book, I’ve only ever read A Theft (a 128-page 1989 novella) and the classic and brilliant Herzog (a 1964 novel). But there is something so profoundly, incredibly fresh, original and insightful about Bellow’s prose—especially as things stand from the perspective of contemporary 2023—that I found myself with mouth often ajar, writing marginalia and highlighting dozens of lines, passages, paragraphs and even whole pages due to the relevance.

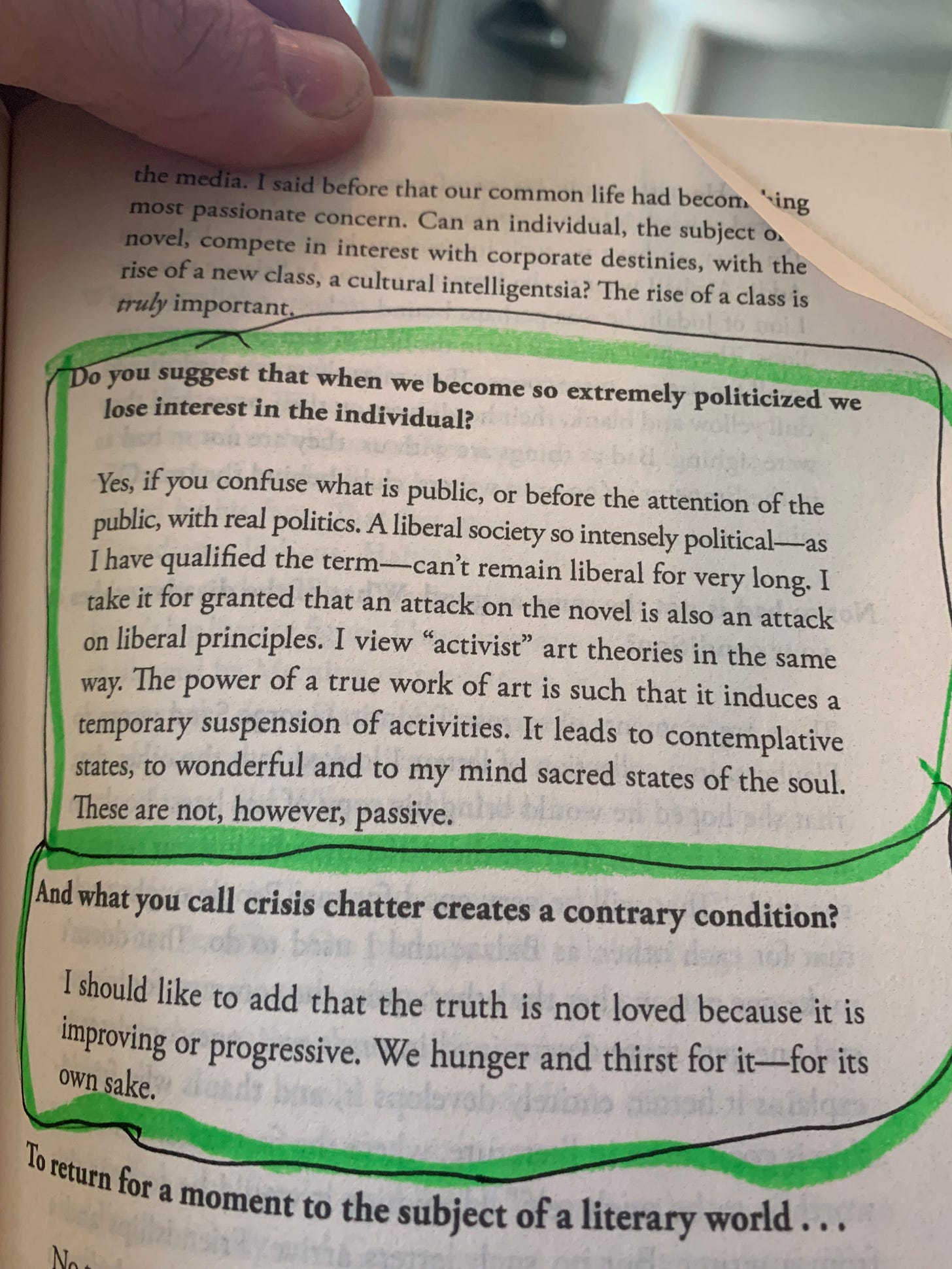

Bellow seems to have been a man—a writer—who strongly believed in the inherent value of Art. New developing technology worried him, as it has and currently very much does worry many another writer. (Me included. AI terrifies me in terms of what it might do/already possibly has done to Art.) But despite the many techno-hurdles society has and still might throw up at us (the writers, the artists), Bellow’s Comanche cry was always more or less the same: Fuck it, create Art anyway. He believed in the notion of a “spirit” or “soul.” He believed that the idea of Art was meant to transcend rational thinking and science and the intellect, lovely as those things all may be. There is something greater Man has always strived for and that thing we call Art.

He was also a powerful denier of the morbid fantasy of “identity” and ideology. Once criticized by the Jewish community for referring to himself in an interview as an “American writer” first and a “Jew” second, he did not back down. To him he was a writer; that was what defined his soul, his passion, his mind; it’s what ultimately created order out of the inherent chaos that was his existence. He grasped intrinsically—and intellectually—the “totalitarianism” of ideology and how it taints the waters of pure art.

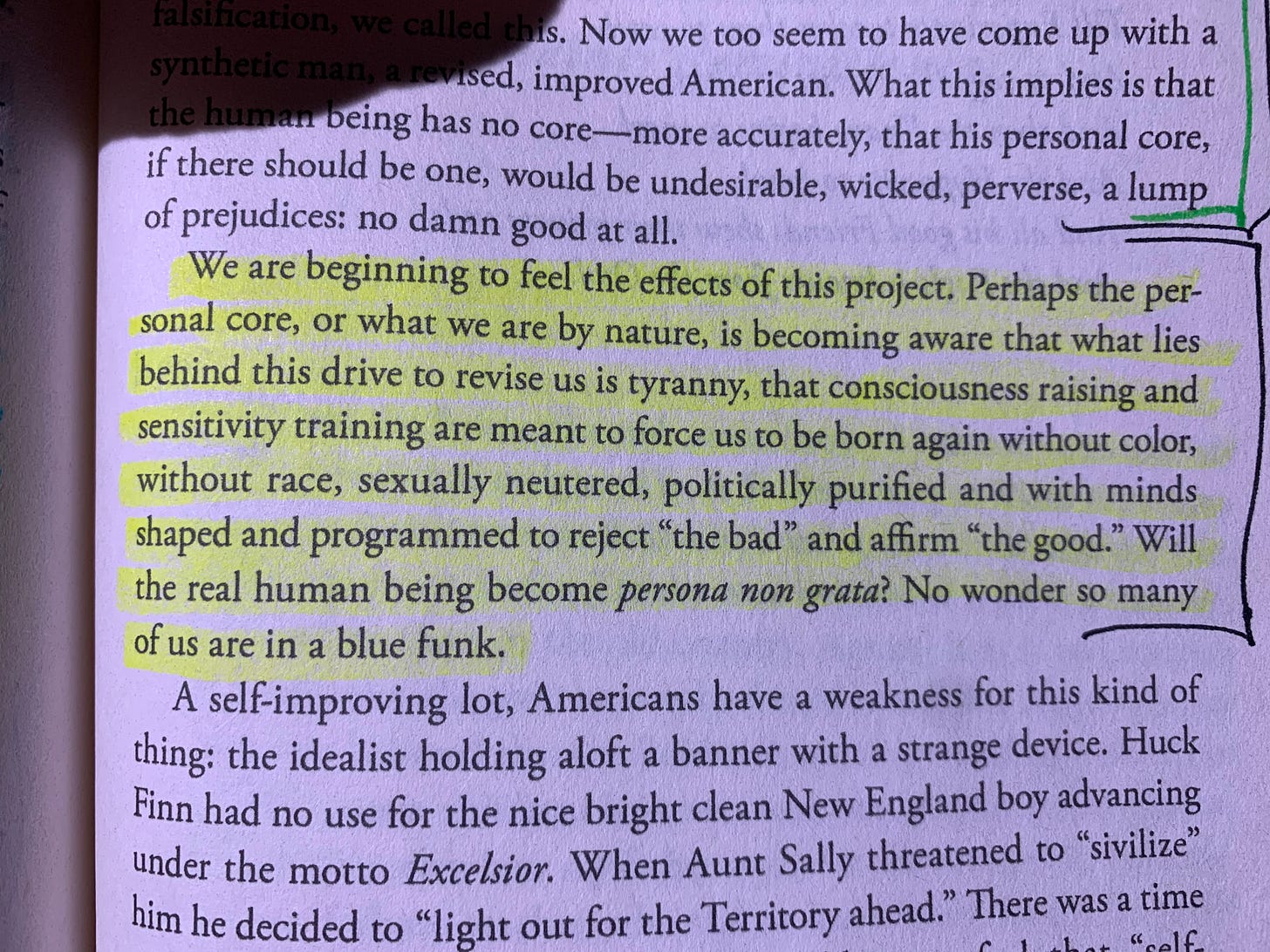

At no time has this been more crucial to understand than our time now, a time of Woke conformism where thinking itself is seen as degrading; you’re supposed to stick to your “tribe” and verbally vomit your knee-jerk tribal qualifications, no more is required of you. This tribal subjugation, of course, has zero connection to Art, or to anything else related to true honest expression or honest appraisal of the human condition. Instead it is rote, dumb conformity and the loss of the thinking mind. Brains have been turned off. Eyes have been closed. Mouths, stupid and moist, flaccidly gape open and shut closed without saying anything new or of any real worth.

Bellow owns his own insecurities and literary/intellectual pretensions. He knows he is “high brow,” yet he (joyously) condemns the moronic institutionalization of literature and writing, the Lit professors who instead of writing or living anything resembling a “real life,” yap aggressively on and on and on, ad infinitum, “about” writing and literature. As Bellow writes over and over in various ways and from different angles: It became, at some point, probably during the volcanic cultural ruptures of the turbulent 1960s, more trendy and common to “act” like a writer than to actually “be” a writer. The acting, Bellow argues, is fun and easy and scores you prestige points. The art, on the other hand, is difficult, slow and arduous. He doesn’t write exclusively about the proliferation of MFA programs but he might as well have. The idea that professors are going to “teach” you writing is, to Bellow, absurd. He, like so many other writers—Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Kerouac, Miller—was an autodidact.

Bellow firmly pushes us—sometimes it feels like a loose scream—to dive underneath and beyond the superficial and the mechanical and to think independently; he yearns for us to go back to The Individual. The book is a collection of nonfiction essays covering chronologically the 1950s to the 1990s and 00s. Sometimes the essays are partially or entirely about earlier times, but they were first written by Bellow in said era. The explosion of the 1960s seems to be the game-changer. And before that the explosion of World War II and the subsequent creation of Israel. The rise of the New American Empire, taking over where the then-defunct British Empire had left off.