An Adventure in Spirit and Road: Canada and Alaska, Part 3:

Running the Symbolic Gauntlet, Part 3

(Above.) Grizzly Bear in Hyder, Alaska killing a spawning salmon, blood and eggs going everywhere. Brutal!

Like my writing? Here are some ways to support me:

1. Re-stack this post

2. Share with friends and family

3. Subscribe for free, or paid $5/month; $35/year; $200 Founder

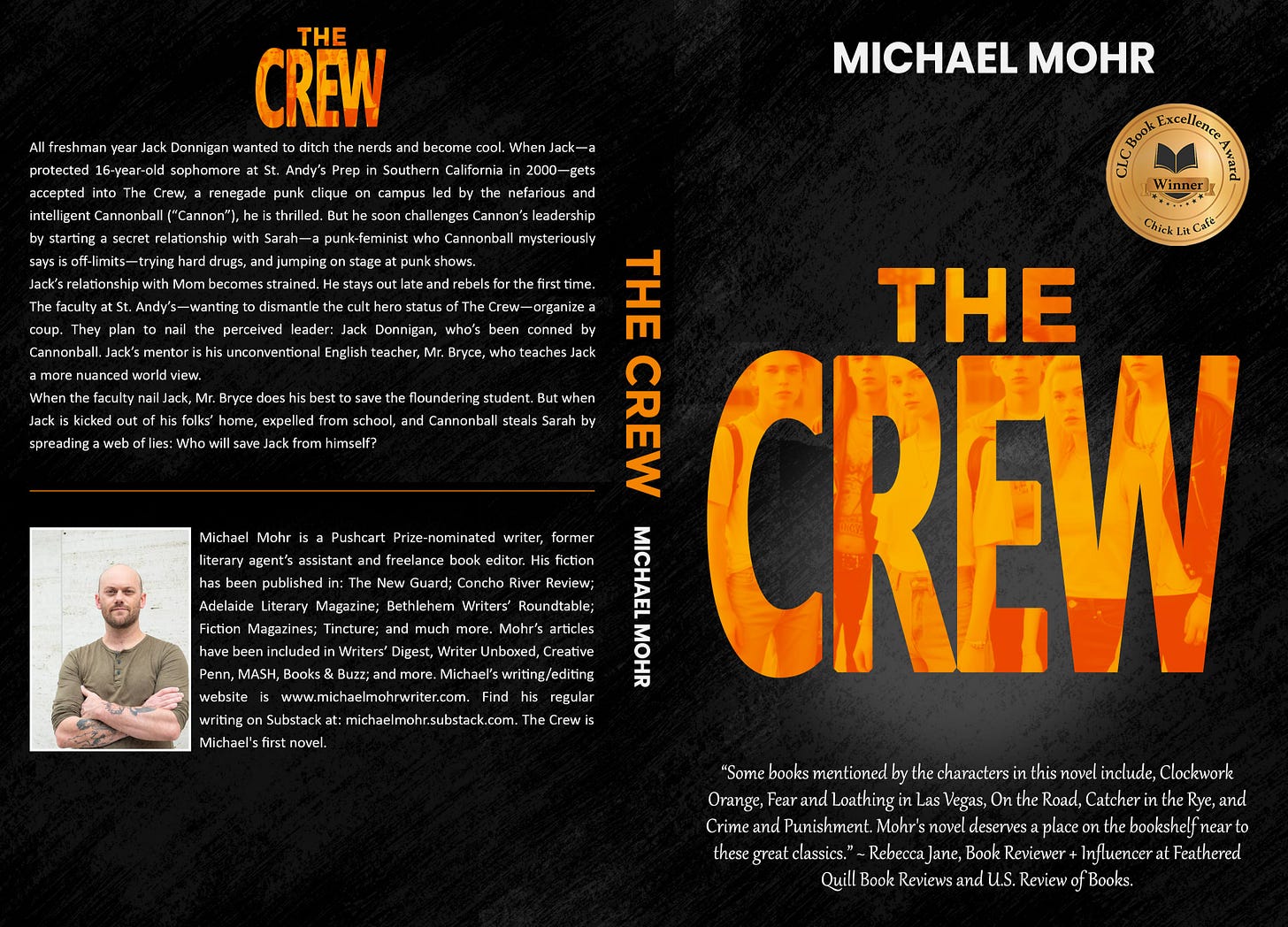

4. Buy my literary YA novel HERE ($3.99 eBook) and review it on Amazon (the book is available everywhere now: Ingram Spark, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop.org, etc etc)

*

Read Part 1 here

Read Part 2 here

~

I’d sold the house in the Bay Area I’d owned for nearly a decade, since 2015. I’d been a mere, angelic, innocent 32 back then, which now, at almost 42, felt like an eon ago. What a different time. Before Covid. Before NYC. Before Britney. Before my father’s death. Before Trump, even. The last contemporary time of innocence in our modern society, one might say. And now that time was gone, erased like the miles used up as the car sped along Highway 97.

And, of course, my inner trek, which, for me, was the most important odyssey of all. I’d changed. Britney had too, it seemed. Every adventure, every trip, every journey—not “vacation”—changes you. I already felt like an old snake with fresh skin. I’d shed my old being, my old self. The road had changed something internal, something symbolic within me, as the road had always altered my inner life.

I handed our brand-new passports (good until 2030) over to the late 50s white-haired Canadian customs officer. He took them, unsmiling, and began punching things into an unseen keyboard; the sounds of the keys clacking were familiar. I glanced over at Britney, who shrugged slightly. Fingers crossed.

After a few minutes of tense silence the customs officer said, “Have you ever been denied entry into Canada, Michael?”

My heart froze. A chill tingled down my spine. I glanced at Britney again; now she seemed worried.

I faced the officer again. “Yes. 2009.”

“And what was the reason for rejection?”

Breathe, Michael.

“DUI, from 2003.”

He nodded and faced his computer again. Fear tore through my solar plexus. This. Again. Now 21 years after the damn DUI, a “crime” which had been lowered to an infraction. I’d been sober now just shy of 14 years. When would I be forgiven? Or would I?

The officer asked a few more general questions about why we were entering Canada, for how long, asked me to roll the back windows down, etc. (The car was full to the brim with camping gear.) And then he handed the passports back and said, “Ok. Go ahead.”

Relief surged through me. It had been frightening but we’d made it in without having to pull over and go inside the building like I’d had to do in 2014. No awkward, brutal humiliation. No good cop/bad cop routine. And it was done.

Or so I thought.

*

We crossed into Canada and caught Trans-Canadian Highway 1, which we’d take until switching around Cache Creek, B.C., to Highway 97, before switching once more to Highway 16 heading west at Prince George, also known as the Highway of Tears due to all the [often Indigenous] teen girls who’d gone missing and/or been murdered along this road since the 1960s. (Britney knew all about it of course because of her true crime obsession.)

The landscape quickly became absolutely gorgeous: Tall rugged mountains, some with snow around the peaks, Lodgepole Pines and Balsam Fir trees absolutely everywhere. Lakes, rivers, creeks, fields of natural green in a variety of nuanced shades.

We ended up staying not far from the border, a little north into B.C., splurging by staying one night in Harrison Hot Springs. We’d mostly been camping both before and after Portland, and we’d just closed, finally, on the two houses. It was time to celebrate, to live momentarily in luxury. The hotel was stupendous, right on the lake. We relaxed in the natural hot springs, ate a delicious meal, and got some well-needed sleep on a real bed.

The next morning we took our time. I got up early and went downstairs. I found one public computer. I used it and wrote post #1 of this four-part series. Britney did her own thing. We packed and hit the road. We ended up camping on a married couple’s farm in the little town of Quesnel, B.C., about 400 miles north of the Washington/Canada border. It was a “Hip Camp,” which Britney had found us. (There’s a Hip Camp app; it offers places to crash which are camping or similar to camping, sometimes “glamping.”)

The farm was gorgeous: 13.5 acres run by a woman in her mid-fifties and her husband, who happened to be out of town working. She was very kind. She showed us where to park the car, where we’d pitch a tent, and then toured us around the farm showing us the myriad animals in various pens: Sheep, horses, chickens, pigs, ducks, etc. There were half a dozen dogs running around the property, free as birds. One cat. Besides running the farm, she also ran a little ice cream shop. Sometimes, she told us, it was empty as a baby’s brain; other times it was jam-packed. It felt like we were in the middle of nowhere, so this seemed strange.

She also had a new litter of puppies. Tiny little things, a rat terrier and others which almost looked like Labs. Cute as hell. She brought them out and we held them. This was joyous. Eventually, she left us to ourselves. Britney and I did a nice half-hour walk along the bucolic road surrounded by Balsam Fir, the glorious mountains in the distance, small rural farms dotting the landscape here and there as we passed. We knew we were in Bear country but I didn’t feel afraid. Britney did. But I figured we’d be fine; everyone had told us that bears—whether Black or Grizzly—were generally afraid of us. As long as you didn’t run or provoke them you’d almost always be ok. Still, we carried Bear Spray which I’d bought backpacking in Yellowstone back in 2015. Just to be safe.

*

The next morning I woke up early, before Britney. Oddly, this had become the new norm on the road. While home in Lompoc, she’d always gotten up first, around 5:30am, stirred by the cries and needs of our animals. But here, she slept and I got up. I chugged water and made Irish tea—my usual routine—and walked alone amidst the silence and trees and mountains, through the farm and out into the empty country road. I walked for maybe 25 minutes, at one point pausing and listening to that still, profound, utter silence, and then entering a flat green spacious field, gaping at the organic raw beauty.

I couldn’t wait for Alaska. We’d decided on going to Hyder, one of the most southeastern sections of Alaska, right across the border from Stewart, B.C., in the narrow, long southern tail of Alaska. We wouldn’t be fully going “into” Alaska proper, aka into the major meat of the state, i.e. Fairbanks, Anchorage, etc. So no romantic Chris McCandless experience. Not directly at least. Still, it was Alaska, at least technically. It would be less like visiting the final frontier and more like running a race and touching down for a moment before turning and sprinting back to California. We wanted to save money and time, that was the main thing. We’d begun to realize our expenses had been more than we’d expected.

We’d googled things and discovered Hyder, a tiny town just past the B.C. border, about 65% of the way north to the Yukon border. Up in northern B.C. The town, we read, was an hour via dirt road from America’s 5th largest glacier, Salmon Glacier, which was 14,000 years old. Also, a mile away was Fish Creek, where there was an official boardwalk along the Salmon River which allowed you to observe the frequent Grizzly Bears. The town was situated at the confluence of the Salmon and Bear Rivers.

I couldn’t wait.

*

Because there’s no logical way for anyone to get into the mainland of the USA via Hyder—the mountains quickly become B.C. territory again, once in Hyder, including where the glacier is—there is actually no U.S. Customs going from B.C. proper into Hyder. But, of course, anytime you leave Hyder—to, say, go into town for dinner in Stewart, B.C., the town just across the border, since there is nothing at all except campgrounds in Hyder—you must go through Canadian Customs.

We ended up staying at a really cool RV/tent spot called Eagle Shadow Campground in Hyder. The place had been purchased by a Morman family from Pennsylvania a year ago. There were about a dozen RVs packed in. Exposed tents were not allowed, due to bears. They had started using an old abandoned metro bus—with a still-functional hydraulic door—which had been left there when they purchased the land, for tent campers. Inside the bus were three solid, sturdy, thick tents. We were the first and only people to use the bus. It was fantastic. (And of course it brought back to mind Chris McCandless, who lived and died in an abandoned school bus 28 miles west of Healy, in the Denali National Park in Alaska.)

The drama started later that night.

That evening we drove the one mile to Fish Creek and walked out onto the tall wooden boardwalk along with other tourists and we saw a pregnant female Grizzly lazily (she’d previously eaten her main meal, a guide said) trying to catch and eat salmon. The salmon, it turned out, were spawning, meaning they were fat and pregnant and swimming upstream, where they’d birth their eggs and then die. This reminded me of going down the Rogue River in Southern Oregon in 1994, when I was a boy, with my best friend and my folks on a five-day trip. I’d seen fish spawning for the first time and had tried to literally catch one with my bare, desperate hands. (I failed.)

All of that was great. But then we decided to get pizza at Silverado, a little local place in nearby Stewart, five minutes away but across the Canadian border.

I drove slowly through Hyder, aware of the quiet and the bucolic relaxed nature of the place. It almost felt holy here, if not strangely mixed with a sort of American South hillbilly white trash edge. (J.D. Vance’s 2016 memoir, Hillbilly Elegy was on my mind since I’d recently reread it and since Britney was currently plowing through it with gusto.) Some cabins were falling apart. Old, time-beaten men sat on chairs eyeing the road, looking stern. It possessed an eerie feeling and, combined with the raw natural beauty, produced a feeling of slight terror.

We slowed at the border, behind a big black truck with B.C. plates. A young man probably a decade younger than me approached. Despite his thickness, muscles and uniform with the gun, mace, etc, he seemed relaxed and kind. I rolled the window down. After taking down the license plate number and taking our passports, then typing on his iPhone, he asked me “what happened in 2009?” I explained. He listened, nodding his head. He walked off into the small building for a minute. When he returned he said, “Can you pull over to the side?” He glanced in the direction of the small dirt lot 50 feet away.

We pulled up to the lot. Britney was surprised. I hoped it might just be a fluke, or something random. But when a few minutes later the young customs officer approached our parked car on my side…I knew what it was. Of course.

“Sir, can you step inside with me please?” he said through the rolled-down passenger side window. Yep.

Long story short: I went inside for about 45 minutes. There were three officers; the young guy, an older bald man, and a woman in her early fifties. The young guy and the woman were both friendly. The bald older man was neutral, if slightly unfriendly. All three hovered around computers, passing my passport around, asking me questions about the DUI in 2003, about what happened in 2009, what happened in 2014, if I’d had my record expunged, etc. I explained the whole story from beginning to end and mentioned how humiliating it had all been, that I’d been sober a long time now, that the DUI had been lowered to an infraction, that I’d had my U.S. record expunged, and that I was only 19 when I got it, a damn kid.

They all listened sympathetically. The computer was glitching up which wasted more time. I knew Britney was probably freaking out, not only because of my issue but because she’d had her own issue crossing into Canada with her sister back in 2017.

The woman—who was currently highest in command—said she understood and that she would try to put a note in the system saying that I was “ok,” but that the reality was, due to the DUI laws in Canada changing multiple times, and due to when I got my DUI and when I tried to hitchhike across the eastern border in 2009—the hitchhiking didn’t help, she added—she thought I would probably always have this DUI on my Canadian file, for the rest of my life.

That said, she again reiterated, she’d add a note on my file and, she said, she’d try to contact her higher-ups and see if anything could be done. She also said there was a process I myself could take to petition the Canadian government to remove the “flag” in the system. My status, she said, was “partially redeemed,” meaning, basically, I was admissible but they could and would forever give me shit. In 2014, the customs officer had told me if I wanted to get into Canada again I would have to “get my record cleared.” I had done that, in 2018, but only on the legal USA end.

Finally, they let me go. I felt grateful it hadn’t been worse, but also frazzled, angry and resentful. This bullshit yet again. Who’d have thought I’d pay for one dumb choice 21 years ago that was an infraction. But that didn’t matter; that was America’s assessment. This was Canada. Two different countries with two different sets of laws, culture, ideas, taboos, norms, etc.

*

The following morning we got up early. We’d decided, despite the border fiasco, to stay one more day and night in Hyder. We’d get up tomorrow and head out, back into Canada and eventually the USA a la I-5 and Washington, Oregon (where we’d stop in Portland again, and this time actually sleep in our new house, in our sleeping bags and on our thin pads) and finally home.

It had already been a long trip: Though it had only actually been eight days since we left Lompoc on August 4th, it somehow felt like we’d been on the road for a month or even six weeks. So much had happened, both externally and internally. We’d closed on two homes. We’d decided to move to Portland. We’d had the border problems. We’d driven 2,100 miles from home. I’d seen my real estate agent/friend (friend of 25 years) in the flesh for the first time in many moons.

And, of course, my inner trek, which, for me, was the most important odyssey of all. I’d changed. Britney had too, it seemed. Every adventure, every trip, every journey—not “vacation”—changes you. I already felt like an old snake with fresh skin. I’d shed my old being, my old self. The road had changed something internal, something symbolic within me, as the road had always altered my inner life. Though we hadn’t been hiking—Britney was terrified of being mauled by Grizzlies, despite the data—we’d been car-camping. I felt dirty in the best way: Natural, raw, exposed in nature, like “earlier man” 15,000 years ago. A part of the Earth, not something alien and separate. Many times on and off we lost cell service, and this I cherished most of all, even if simultaneously being annoyed that I couldn’t check my Substack.

I’d sold the house in the Bay Area I’d owned for nearly a decade, since 2015. I’d been a mere, angelic, innocent 32 back then, which now, at almost 42, felt like an eon ago. What a different time. Before Covid. Before NYC. Before Britney. Before my father’s death. Before Trump, even. The last contemporary time of innocence in our modern society, one might say. And now that time was gone, erased like the miles used up as the car sped along Highway 97.

We were in the Prius by 6am. Soon we parked in front of the Fish Creek boardwalk. We paid and entered. Within ten minutes there was a big male Grizzly catching salmon easily. We and the others—perhaps 30 people in all—followed the bear back and forth, snapping photos, videoing, gawking like ludicrous imbecilic weirdos. As if we were the human paparazzi eyeing the non-human celebrities. The bear was huge and brown with the signature hump. I imagined him standing and growling, but this never occurred. But he did at one point catch a salmon, place it on the ground, and bash it so that blood and eggs spewed out of the fish like a grade-B horror film. We recorded it. See video!

*

After the bear sighting we decided to risk the border again. It was “CBT,” I thought: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; exposure therapy, the new trendy idea that in order to face your fears and eliminate your OCD/anxiety, you must face in real time the same fears again and again and again.

Well, here we were.

I expected the same three people as the day before, given the tiny size of Hyder and the tiny building and smallness of everything.

I was, once again, wrong.

This time it was a medium-build South Asian—possibly Indigenous—woman. She walked over, stern as always, and asked for our passports. I handed them over and immediately preempted what I knew would come. I summarized the 2003 DUI, what happened in 2009—“What happened in 2009?” had by now become a comedic, absurd tagline Britney and I threw randomly at each other—what happened in 2014, etc.

She nodded, listening. When I said the other customs people had “already resolved this” she snapped at me that she’d do her own research and that she didn’t care what anyone else had previously said. I glanced at Britney who gave me The Look (as in: Shut your mouth before you make things worse.)

She said she’d be back. We didn’t get told to pull over. She walked with our passports back into the tiny building. We waited, silent. My heart pounded in my chest. Why did I feel afraid? I hadn’t actually done anything wrong. It was ridiculous.

Half an hour later she strolled back out. She walked to the driver’s side and handed the passports back.

“Next time you should be fully honest with me,” she said.

“I’m sorry?”

“Turns out it wasn’t just a DUI from 2003, it was also driving without a license. Lying will never help your case.”

I genuinely had no idea about the driving without a license charge. I’d never been told this, and I hadn’t seen it on the copy of my criminal record which I’d had mailed to me in 2018, when I had the DUI expunged.

“I honestly wasn’t aware of that.”

She smirked and went on to explain again that I was “partially redeemed” and that this would always and forevermore be on my Canadian customs file.

“Will Canada ever let this go and forgive me for something I did 21 years ago? It makes me feel like I’m a bad person.”

“There are no good people or bad people, just people who make mistakes,” she said.

“Right. But it was 21 years ago. I was 19 years old. A kid. I’ve been sober almost 14 years now. I do AA. I have to tell you, my experience in 2009 and especially in 2014 going through Canadian customs was absolutely humiliating. I seriously have PTSD from the experiences. I’m a good person. I don’t deserve this treatment.”

As I spoke—I may have heard Britney try to calm me down—I kept my voice medium and wasn’t overly emotional. I could tell that the customs official was experiencing true empathy for me; her eyes looked directly into mine and held the gaze of honest caring and humanity. She sympathized, I could tell that. She had told me she was a “senior immigration official” and thus had more power.

She let us through. We took off, into Stewart.

*

After eating in Stewart we returned to Eagle Shadow Campground in Hyder. We chatted with the young man probably in his thirties who nonetheless appeared to me to be in his early twenties. The day before we’d met his younger but physically bigger brother. Both said they’d been to “all fifty states.” Neither feared bears. They ran the place with their parents. The man we spoke with now was kind, smiled a lot, conversed eagerly and openly, and had bright red burning cheeks, like a child. He told us about the property, his family, bears, hiking, the glacier, etc. Britney asked him a billion and one questions. She’s like my research assistant. She asks and listens. I hang back in the shadows. I write it down.

We showered (believe it or not neither of us had showered for 5-6 days!) and did laundry which they had on site since it was mainly an RV park. All the RVs minus two had left; the place was largely empty now.

The following morning, before heading out we drove the one hour along the winding, pothole-filled road up to Salmon Glacier. We sipped self-made coffee and tea, windows down with the cool Alaskan (and then Canadian) air rushing in, and music playing low-volume.

The glacier was heavenly, Lordly, awe-inspiring, surreal. Words are hard to describe it. Fourteen-thousand years old. Wow. We parked and gaped at the blue-white thing down below, stepping onto a ledge that offered a better look. I hiked for 10 minutes without Britney, along a narrow trail passing through little ponds and creeks, boulders and Lodgepole Pines. The views were otherworldly.

*

After the glacier and the hour return back to Hyder, we once again, for the 5th and final time, crossed through the Canadian border. After that it would be only the U.S. border in the south going into Washington State. So, this was it. The finale. What, I pondered out loud to Britney as we drove, would be behind Door #5?

Rounding the turn, slowing for the customs crossing, I saw that it was yet again a new officer. This time a white short-haired lesbian woman in her fifties, it seemed.

We pulled up. I rolled the driver’s side window down. I started to tell her “what happened in 2009” when she laughed and said, “I know all about it.”

“So we’re famous, huh?” I said.

“Something like that.”

She avoided my eyes, punching things into her official cell phone which doubled as her customs info machine.

After a few minutes she said, “Look’s like you’re good to go.”

“Really?”

“Yep. You didn’t flag at all this time.”

Then the door to the tiny building opened and out emerged the South Asian senior official. She came over. She said she had “assessed your criminality” more thoroughly and had decided to change your status from “partially redeemed” to “fully redeemed.”

I couldn’t believe it. I felt like crying. I felt like getting out of the car and bear-hugging her. (Pun intended.) I felt like celebrating!

“So,” I stammered, “That means I won’t ever flag again?”

She smiled. “As long as you don’t commit another crime.”

“Right,” I said, grinning.

“Thank you,” I said, gazing into her eyes. “Seriously. Thank you.”

“You’re welcome.”

They waved us through and that was that. I was floored, stunned, shocked. This was what happened—sometimes—when you were open, honest, sincere and you accepted life on life’s terms, and you let the pieces fall where they may. I felt forgiven by a country. Accepted. Redeemed. Given a second chance. Grateful beyond words.

We exited Alaska once more back into Canada.