Thirty-nine-year-old J.D. Vance’s 2016 memoir, Hillbilly Elegy, has become yet again an instant bestseller and a #1 Netflix hit (the book was made into a film in 2020) recently after Vance was picked as Trump’s VP running mate for the 2024 presidential run.

Let me be clear right off the bat: I am not a Vance fan, at least not in 2024. Many reasons for this, but two main ones:

1. He is profoundly anti-abortion, even in the case of rape or incest. Only when the mother’s life is threatened does he budge here.

2. In 2020 he made false claims about election fraud, along with Trump, about the cleanest election in U.S. history.

As is expected in our intense, tribal, polarized moment, many on the left have pounced on Vance, and specifically on his memoir, Hillbilly Elegy.

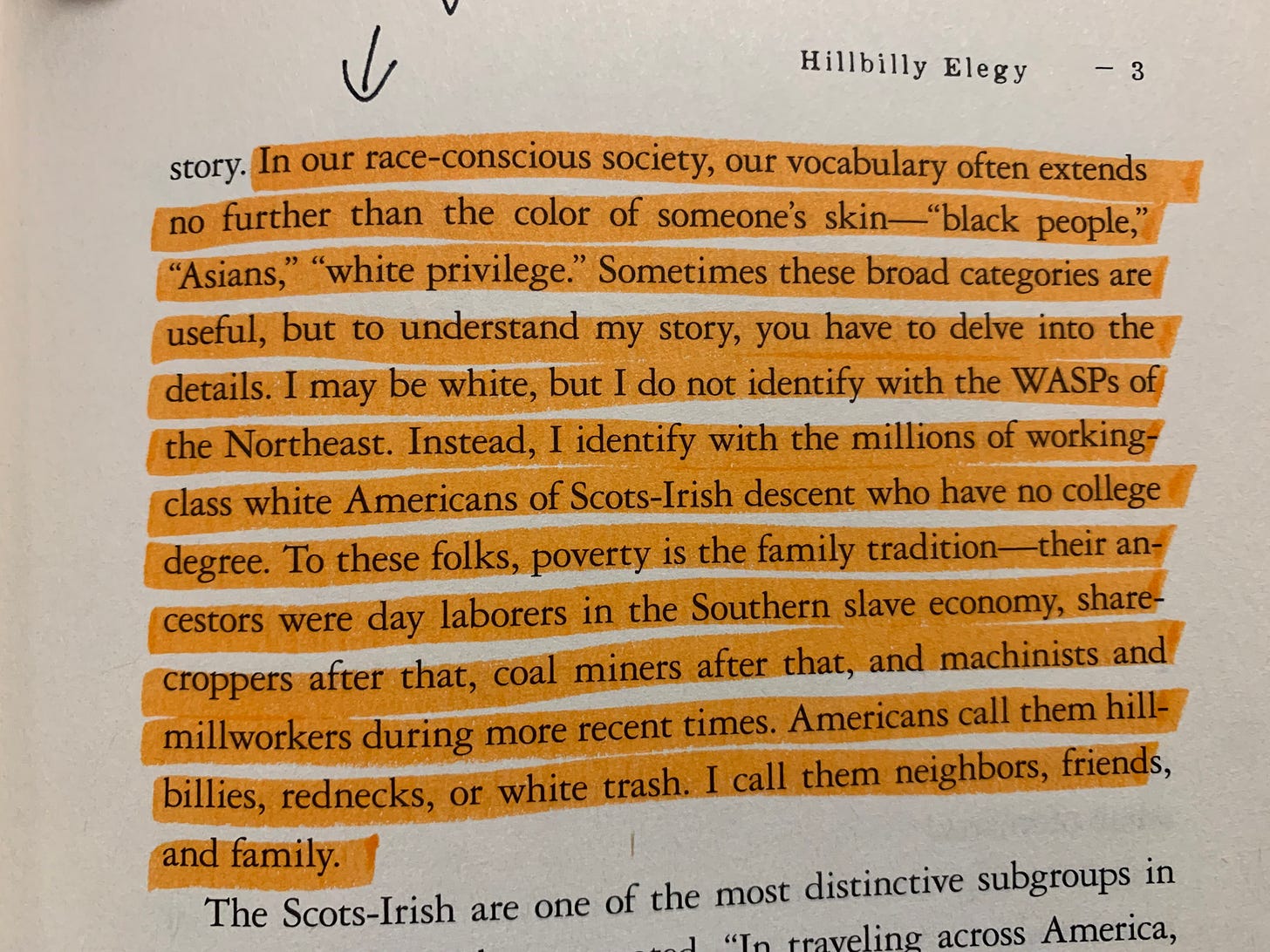

I read the memoir for the first time in 2022, when I was caretaking for my father during his terminal cancer. At the time I lived with my parents temporarily, downstairs in their beautiful Santa Barbara home up in the hills with a view of the whole town and the ocean. At the time, the book struck a deep nerve. I’d never read anything like it. Especially during our time of identity politics—on both political sides—it was interesting to read a white man’s account of poverty.

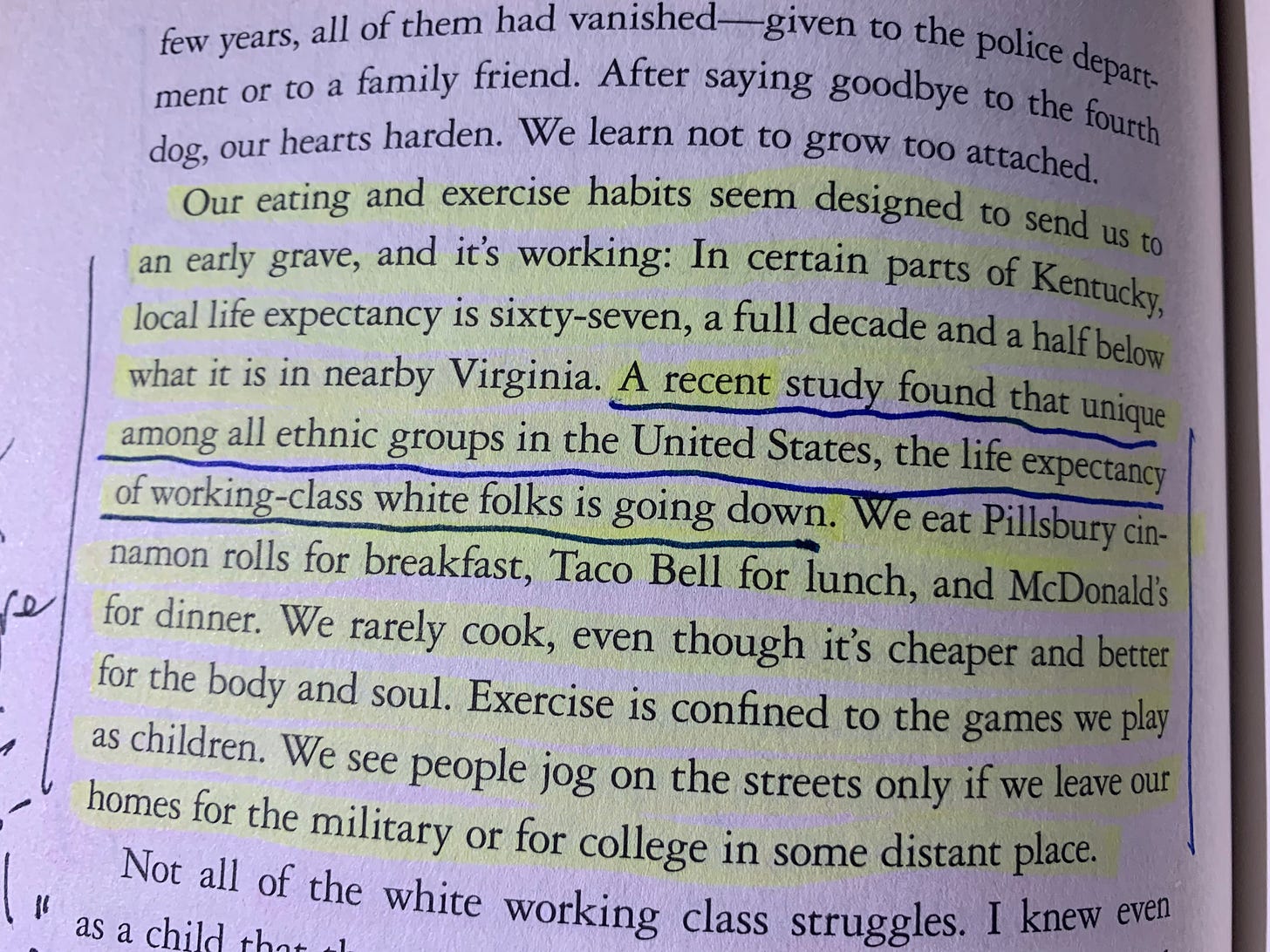

The memoir is about Vance’s upbringing in a poor white family in Eastern Kentucky—Appalachia—and then in Ohio, in the “industrial Northwest.” Vance was born in 1984. (I was born on the last day of 1982, so we’re peers.) He writes about the incredible poverty around him growing up in a bucolic mountain town filled with welfare, section 8, food stamps, drug addiction, violence, fatherless homes, too many kids to take care of, foster care, you name it. Like many low-income Black and Hispanic kids, Vance, and many whites in his milieu, was largely raised by his grandparents. His father split and his mother was a drug addict in and out of rehab and jail.

Eventually, Vance finally gets three years of peace and quiet—away from his toxic mother’s constantly moving wheel of new boyfriends and husbands—living with his beloved grandmother, whom he calls Mamaw. He starts going back to high school classes, does well, and gets into Ohio State for college. (The only one in his family to go to college.) From there he works hard and makes it—unbelievably—into Yale Law School¸ replete with huge doses of financial aid. (He claims it’s actually “cheaper” to go to the Ivy League schools than state schools for poor kids due to massive aid packages.)

Two days ago, thinking about Trump and therefore Vance—the first millennial VP—I decided I needed to reread Hillbilly Elegy. A day and a half later I’d consumed it, complete with new marginalia and highlighting. It’s a fun, solid, easy and enlightening read. I highly recommend it.

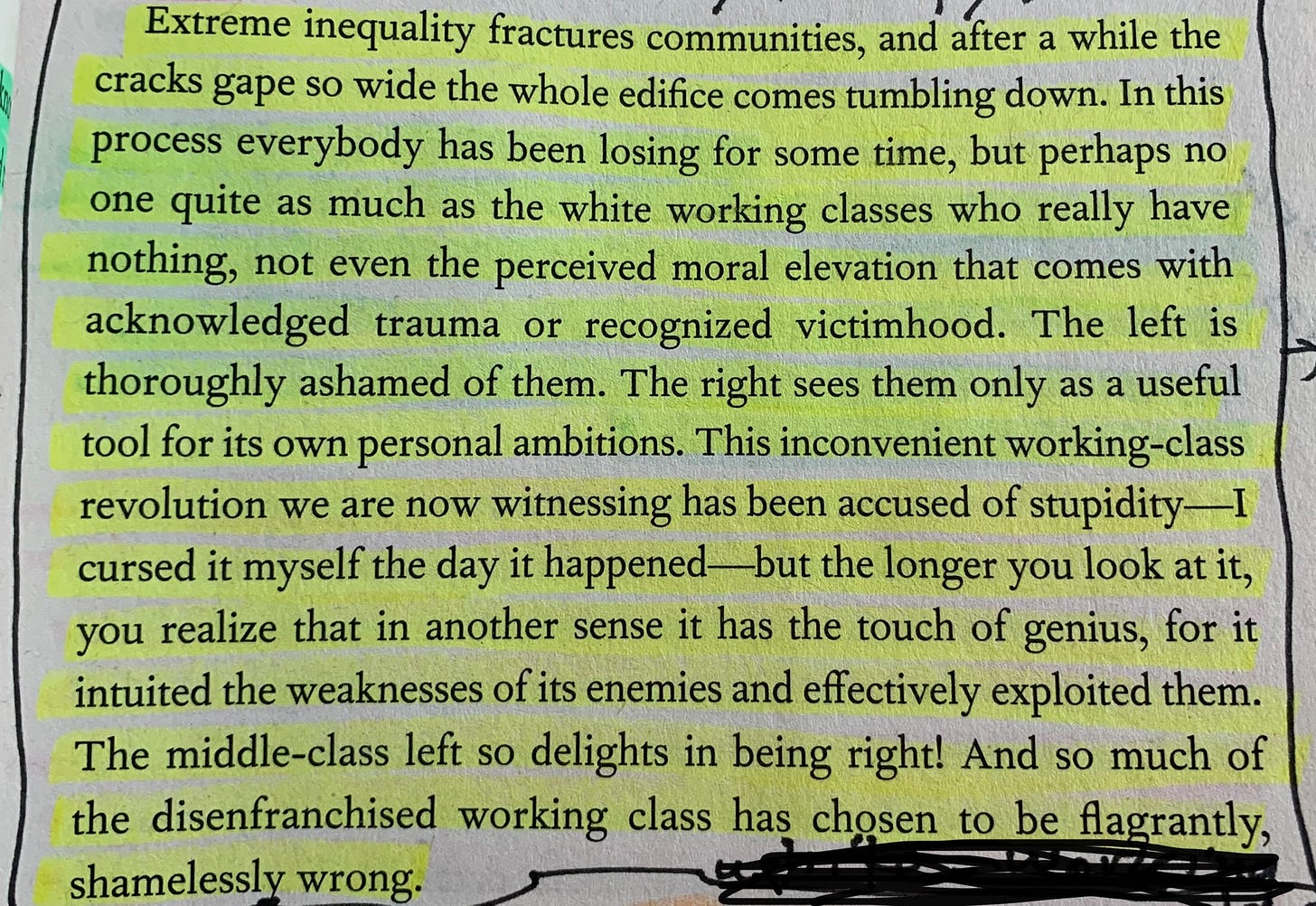

What hit me the hardest was the ironic similarities between Vance’s description of poor whites and those of urban Blacks living in inner cities. Ditto Hispanic, Asian, etc. I’ve always felt more on the Bernie Sanders circa 2016 side of things: Towards social class and away from identity politics. As Vance expertly points out: The working-classes of all races and genders have much more in common than people of the “same race” within different classes.

I have found this deeply true personally. I guess it’s fair to say I’m a bit of a class warrior of sorts. I grew up upper-middle-class and white; privileged. I’m much more interested when I encounter someone of roughly my class, regardless of race or gender, than I am of someone who happens to be white but they’re not in my class, roughly speaking. In other words: I am much happier to dialogue about philosophy or literature with a Black writer than, say, someone I consider to be “white trash.” This has always felt naturally obvious and true for me.

There are a lot of crucial messages in Vance’s memoir. When Trump came to power in 2016 many on the left—AOC I’m looking at you—claimed the reason was obvious and simple: White anti-Black racism. This isn’t surprising, of course: We live in the of time of Twitter (X) and TikTok: We like the grotesquely binary and simple versus the human, messy and complex, the nuanced and deeper truths.

Trump-hater as I was back then—and still am—I never bought this argument. As a group the white working-class in the swing states had overwhelmingly voted for Obama in 2008 and 2012. Trump came to power in 2016 for several different reasons:

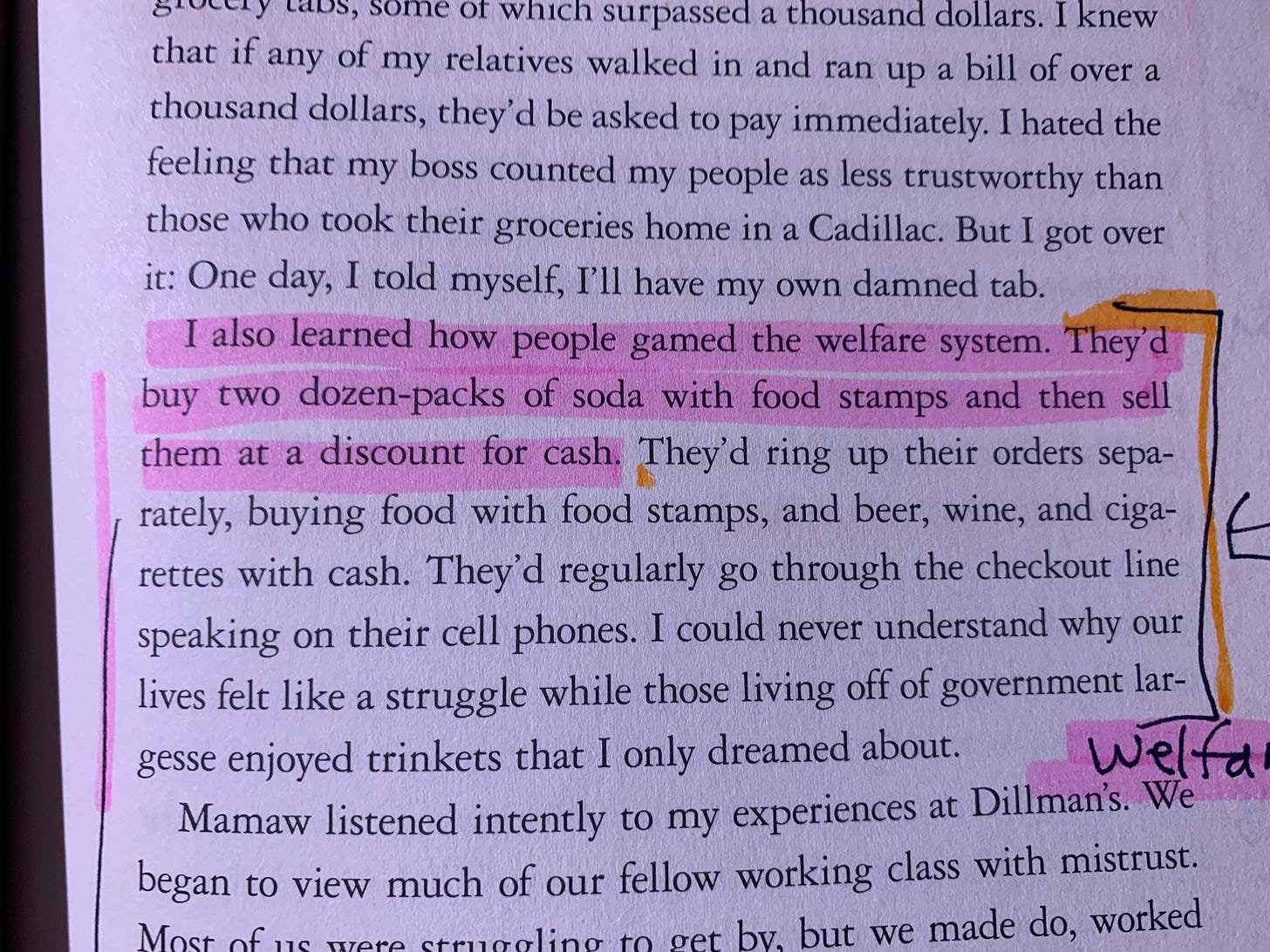

1. Democrats had, for the past few decades, started to shift further and further away from the working class of America. Vance tells us in his memoir that for generations his family and Appalachian families like his had voted Democratic. This started to shift in the 1990s and early 00s, when steel mills and coal towns downsized and fled overseas and became taken over by AI. Add to that the Democrats’ well-intentioned but paternalistic need to hand out free money to poor people in the form of Welfare—often disincentivizing people from working and keeping them poor and addicted to drugs—and that was enough to switch teams.

2. Democrats have become more and more over the years the party of “Elites,” run by D.C., NYC, Portland, Seattle, LA, S.F., etc. Journalism morphed from a working-class trade to a rich white trust-fund elite NYC experience where you had to have a degree from the Columbia School of Journalism and believe full-throatedly in leftist identity politics.

3. Democrats ran, of all people, the elite, snobbish Hillary Clinton, who was completely unrelatable to America’s working classes. She had a terrible message, a bad campaign, and she spent either no or very little time in swing states before the 2016 election. She thought she had it in the bag.

Now, the more complex truth, of course, is that Democrats weren’t the only ones to fail the working class. Truth was both parties failed. And it wasn’t one party but rather American Progress—ironically—that was hollowing out the industrialized northwest. Both political sides had played a role here for decades. Bigger forces were at work. Globalization was largely to blame: Jobs moving overseas to central and south America and Asia where products were produced for pennies on the dollar and child labor was the norm. AI was on the rise. America hadn’t created a solid social safety net after World War II like the European Union had. Instead it was much more “every man for himself” and “pull yourself up by your boot straps.”

But as I’ve heard many Black thinkers and politicians say as of late, “We didn’t have any boots to pull ourselves up by.” Since the 1970s working-class wages have been slowing and stagnating at the same time millions of jobs have been shipped abroad or eliminated. Meanwhile the cost of things in most places has gone up; a dollar doesn’t buy what it used to even a decade ago. And at the same time as all of this, the working classes, especially white working class people in Appalachia and the rural northwest, have been absolutely destroyed by the ruthless, government-supported opioid epidemic. (People on the left often say, Well what about when HIV and crack hit the Black community in the 80s and 90s? No one gave a fuck about THEM! Reagan did nothing!) I won’t deny this. But: Two wrongs don’t make a right. We should have acted differently back then. We didn’t, and that’s a failure. But we have a chance to change things now.

Over the past decade—and especially around the Trump era—there’s been this persistent myth from the left that white people are all the same: They’re all rich, they’re all privileged, they all have nothing to bitch about, they’re all racist, they’re all bad and pathetic and stupid. The left has a similar paternalistic and racist attitude towards Black Americans: They’re all poor and broken victims of a racist white society, as if all Black people are poor, dumb and victims. (Despite the fact that we have a robust and thriving Black middleclass; despite the fact that we had a Black president for eight years; despite the fact that we now have a Black female VP and a Black female running president; despite that Black voices have risen up profoundly and loudly in film, TV, literature, media, etc etc etc.)

I’ll also add that it’s odd that the left rejected Nikki Haley as being the “first” female and Indian-American governor of South Carolina and the second U.S. female/Indian-American governor in the Republican Party and now the left is calling Vance and his memoir “racist” despite the unifying sentences and themes in his book, and despite the fact that his wife, Usha, is also Indian-American, the first Indian Second Lady. But these facts don’t matter to the white privileged elite left…because, despite their being “of color,” they have the “wrong” politics.

Oh, good ole hypocrisy.

Let’s be clear. Americans are a complex melting pot. Always have been. Most of us came here from somewhere else. We have an array of races, genders, ethnicities, cultures, social classes, backgrounds, etc. This is precisely what makes America so wonderful. Not all Black people are poor, broken victims. Not all white people are rich and privileged. This is something that needs to be drilled into the head of Democrats. Trump won because the Democratic Party failed the working classes. This is why 17-20% of Black Americans are now planning to vote for Trump. Twenty percent!!! One in five. And it’s overwhelmingly Black men. Hispanics are even more so for Trump. (42% as of current polls.) Asians have slid off for Trump as well. Most Black Americans, according to Pew, are center-right of the Democratic Party, not left.

But again, this isn’t really about race; it’s about social class. Vance’s main argument is that yes, there is a systemic function for all working-class and lower-income Americans which has a net negative affect but that—and this is the hard part for Democrats to understand—the solutions in the end are largely based on culture, not government. That’s not to say that Medicaid, social security, Medicare, food stamps and other government payouts are bad. Certainly people need these. But Vance’s point is that, at the end of the day, what is truly needed—and I’d argue this for non-white working-class and low-income people as well—is internal cultural change.

Vance writes about how Welfare creates an environment which incentivizes not working, being lazy, falling prey to drug addiction, etc. Many of his white friends and neighbors became “Welfare Queens.” It crosses racial divides. He writes about—and Coleman Hughes has written about this, too, in the Black male community—how amongst working class and low-income white men in Appalachia and the Northwest, education, “being smart” was in his day and still often is seen as being “a pussy” or worse, for Black kids, “being white.” Life for these populations—white, Black, Hispanic, etc—is largely about working hard, fighting to maintain a rigid honor code, and standing tall.

So in other words: We’re back to that placid 1990s idea of needing new and better “role models.”

Look, as I said: I grew up white and privileged. I am NOT one of Vance’s “people.” But I did grow up around blue-collar kids. I always made friends with kids from the “wrong side of the tracks,” to my parents’ consistent chagrin. I don’t know why I liked these kids better; probably it’s my inherent contrarian nature, which I still very much possess. My parents wanted me to be friends with the safe, comfortable rich kids like me: So I rejected that and went the other direction.

One particular friend, who I’ll call Brian, was my best friend. I basically grew up with him from roughly ages 11-18. He and I couldn’t have been more different. We had a big house in Ojai with a pool and a jacuzzi, two cars in the garage, a big front and backyard. Dad was a computer engineer; mom was a nursing instructor. Both had master’s degrees. I grew up in a loving if complex home, getting everything I wanted. I didn’t even have to do chores.

I went to private Catholic college-prep high school. Brian, on the other hand, lived in a family of five in a 1,000 square foot house with three rooms. He started working around the age of 14. He did chores constantly and did not get financially compensated for those chores. Anything he bought had to be with his own money. No one in his family had ever gone to college. Dad was an alcoholic; mom was physically violent. His two sisters were disasters, both becoming addicted to meth early and having kids way too young. Brian himself barely made it out of public high school and immediately went into the trades, working as a plumber.

So you can see here from my personal example: Two “white kids”; violently different upbringings and different life paths available. I was born set-up for success; Brian was not.

Brian was a lot like Vance. It’s been amazing—and disturbing—to watch the left and the Democratic Party generally completely divorce and detach themselves from caring about the working classes, of both white and non-white Americans. Hillary Clinton didn’t try very hard with this demographic—the “deplorables”—because she didn’t think she had to. This is the massive mistake Democrats have made over the past ten years: Switching from the working man to Woke identity politics. And now they’re losing Black, Hispanic and Asians. Affirmative Action was shot down by a majority of voters of all races.

Dems have always seemed mystified by how someone like Trump—a blatant liar, billionaire trust fund baby, and malignant narcissist—could gain the white working class and increasingly the non-white vote. “He lies all the time!!!” I hear from Dems. “He’s a sociopath!” Etc. And look: I agree.

But none of that matters.

A vote for Trump is less so for Trump and against Democrats. The white working class tried Obama twice and Clinton in the 90s and it hasn’t been working for them. Republicans are no better—probably worse; look at Trump’s tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy—but that doesn’t matter: The working class only has one button to push, and that is showing dissatisfaction at the ballot box. Dems for too long have taken non-white and working class voters for granted, and for too long now they’ve lost touch with these people. Ditto Black Americans; there’s a new generation of young Black men who feel slighted by Democrats, who dislike identity politics and who resent being paternally told that they’re victims. They are expressing their anger by using Trump.

Trump is less a man than a symbol. He’s a symbol of inevitable change in the 21st century, change brought on by American privilege and progress. Globalization, which brings both positive and negative results. The rapid rise of AI. Again, neither political party is to blame for these big-picture changes; this is the nature of our time. But the working class, since the 1970s, hasn’t really heard a solid response to these changes. They’re angry now, sick of being caricatured, denied, not listened to, called racist, called ignorant, called stupid.

Democrats have a real opportunity right now. Biden is out. Trump is looking better and better for many optical reasons (including the assassination attempt) but if we could open up Democrats to someone other than Harris, regardless of race, gender, ethnicity, etc, someone who’s a centrist and a genuine unifier, someone who can appeal to people on both political sides, someone who can talk the language of the working classes of all races (especially in the half dozen swing states), then man, I think it just might be possible to gain traction again and win in November.

But Hillbilly Elegy is a searing warning to Democrats: Don’t get mired in identity politics; don’t coronate Harris blindly like you coronated Biden. Give voters a chance to choose who they actually want. Pick someone in the middle, with deep core values, who could actually win. I’d say Michelle Obama—who polls something like 50% to 39% against Trump in a general election—but she says she’s not interested. I’d say Obama, but he’s not going to run. Maybe Dean Philips, the Jewish Democratic centrist. Gretchen Whitmer. Anyone. Everyone.

Obama might have been the last president who understood that winning was all about broad coalition-building. He was very careful when speaking on race to not demonize white people while praising Black Americans and speaking up against injustice. (Just like Martin Luther King Jr.) Because Obama grasped that you can’t alienate one group in favor of another. Race-essentialism does not work; we know that for sure now; the polls are clear. People are sick of the division and polarization of identity politics and boring culture war. There’s a reason Obama won big in 2008 and came into power with a shocking 68% approval rating, winning white blue collar voters in the swing states: He knew how to talk, how to think, how to unite, how to win.

Obama wasn’t perfect. No president is. All presidents have continued some policies which have been an inevitable process of change, wealth, technology and growth. But the age of grievance and victimization isn’t working; it never did work. That’s another thing I like about Hillbilly Elegy: It asks individuals, regardless of race, to take responsibility for their own life choices. No, not everyone is born in privilege like me. Not everyone has “boots” to pull up. Many are born into environments that are profoundly challenging to overcome. But as Vance argues: What are the parents like? Do they give their kids a free library card and encourage them to read? Do they ask them about school? Do they provide them with love and attention, even if incredibly busy? Are the kids growing up in fatherless homes, or homes where the mother cycles through men every few months? Is there physical abuse going on? Alcoholism or drug addiction?

These are choices, not forces beyond someone’s control. There is so much we cannot control about our lives: When and where we’re born; our race; our social class; whether our parents are loving or not; whether we have a high IQ or not; the culture around us; etc. Just like everything in life, much of the game is all about pure, blind luck. Vance happened to be smart, though poor. He struggled but when he finally had a few years of quiet, living with Mamaw, he was able to excel in high school. That led him to college. Etc. It’s unfair because we don’t even get to choose our genetics, aka our drives, ambitions, desires, laziness or lack thereof, ability to study hard, etc. We can adjust and change some of these things, but only to a degree. But those that come from two-parent stable homes have a much better chance.

As far as Vance himself: I liked the 2016 version of him much better. Back then he was critical of Trump (he called him similar to Hitler, which I think is too extreme but I do see some instinctual similarities), and was much more politically moderate and reasonable. A writer more than anything else. Now he has abandoned his old self and has become Trump’s VP, harshly against abortion rights and spouting off about the election fraud of 2020 without evidence.

What I am saying is: Forget Vance in 2024. Separate the “art from the artist.” (Just like J.K. Rowling getting bamboozled for saying online that she likes Vladimir Nabokov’s novel, Lolita. (Read my piece on Lolita here.) His 2016 memoir stands on its own. Read this book. You’ll understand everything you need to know. When I looked Hillbilly Elegy up on Audible it had over 54,000 reviews and a 4.5 rating. I read through many of them. A lot were from people who’d lived the same life as him and they said some version of, Yep. Vance nails it. This is the story of the American working class. This is my story.

We’d be foolish not to listen to this story, not to heed the warning. Democrats especially need to open their eyes. See and think about ALL Americans, not just non-white and the very rich white elites. You’re missing something between these two poles: The rest of America.

I grew up in poverty on my tribe's reservation. I personally found shared ground with Hillbilly Elegy. Our reservation is surrounded by failing mining, timber, and farm towns so I was peer, friends, and family with many poor white people and had common ground with them. And I think JD Vance, the politician, has betrayed the principles of JD Vance, the writer.

Spot on. I grew up not far from where Hillbilly Elegy took place. For the past 30 plus years, I’ve lived in deep Blue SoCal. The casual contempt and ignorance I’ve heard directed towards rural Red America by otherwise intelligent and educated people has been remarkable