[Karr] feels deeply into nuance and complexity, making herself, Lecia and most crucially her parents not binary caricatures or all evil or all good or victims or oppressors but rather does what good fiction writers do, too: Shows us their ultimate, fragile humanity. She shows us her Daddy and Mother’s good, soft, loving and kind sides. And she shows us their terrible, alcoholic, awful sides.

Rereading The Liars’ Club—poet and memoirist Mary Karr’s classic 1995 expose of her wild Texas childhood—was like reading it all for the very first time.

Some books are like that. During COVID I reread a bunch of books, including Orwell’s 1984 and Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye. I found brand new words, sentences, ideas and themes this round. Of course I did: The last time I’d read either I’d been in my twenties. Novels change because we change. We grow older, gain more hefty life experience, mature, get married, have kids, start families, etc. Our inner worlds expand. And so we see these books from a different, new perspective.

Rereading The Liars’ Club was fascinating.

Mary Karr was born in Texas in 1955, a Boomer. It’s a miracle she survived her childhood, let alone became a respected author. She published several books of poems and many memoirs, including The Liars’ Club, Cherry, and Lit. She was married for a while to a male poet for 13 years, was a single mother for a while, and famously (briefly) dated the epic genius author, David Foster Wallace. (If you want an incredible take on DFW read 2012’s Every Love Story is a Ghost Story, by New Yorker writer, D.T. Max.) She later started teaching English Literature at Syracuse University, which I believe she still does and has done for decades.

The Liars’ Club covers two main periods in her childhood: Texas in 1961, when she was about six-seven, and Colorado 1963, when she was eight-nine. (Between those years, too.)

Daddy (Pete Karr) was an ex-World War II soldier who worked in the oil refinery, as most men did at that time in the small town of “Leechfield,” Texas. Daddy was a tough, bar-brawling, hard-drinking cowboy type who fought viciously with any man who pissed him off as well as with his mentally unstable, overly emotional, nostalgic and wild alcoholic wife, Charlie. (Lecia, age 10, and Mary, age 8, sometimes drive Daddy’s truck around town, Lecia driving, without Daddy, looking for Mom after she leaves drunk and doesn’t return.)

The story basically covers Karr and her older sister Lecia’s long struggle to survive in a household where, if money wasn’t exactly lacking, and love on some level was present, everything else about a normal family was gone. Her parents fought all the time, which included glass shattering, plates being hurled, insults exchanged. Often Mom, usually drunk, took off for parts unknown for a few days, coming back to the house with black eyes and/or still drunk or badly hungover, often with tales of tragic woe or wild stories of being kidnapped, you name it.

Daddy was stable, Mom was not. Daddy had routine, a sense of normalcy, but Mom was unpredictable; you never knew what she would do. Lecia—Karr’s older sister—was only two years older but seemed a world wiser and more aware of adults and how the world worked. The two kids were inevitably charged with trying desperately (and futilely) to manage their parents alcoholism and crazy fighting. Karr had a complex love/hate relationship with her mother and her sister. Daddy she loved through and through, unconditionally; she was Daddy’s little girl, without question.

At seven, Karr was raped by an older teenage boy much bigger than her. She writes about the experience as if it were very mechanical. He had her do this and do that. She obeys and barely mentions the event again. She tucks this event deep into the farthest corner of her psyche. By six or seven she’s already copping drinks of alcohol from her parents. (But she hasn’t yet discovered it as The Magic Potion.)

She describes her loneliness at school, her few close friends she made, how they bonded over poetry and literature and felt like bedeviled outsider-outcasts. She was small and easy to pick on and “weird” and different. (As most inchoate writers are.)

She often gets sent to the principal’s office, who is a class-A sexist and explains to her that she needs to learn how to do womanly thing so that one day she can cook for her husband. When Karr informs the man that she wants to be a poet he explains that no one reads poetry and she’ll starve. Karr is, as a child, precocious, that is clear, but, especially as a girl in the early 1960s, this only gets her in more trouble. Little girls weren’t supposed to be smart, deep, intense or probing at that time.

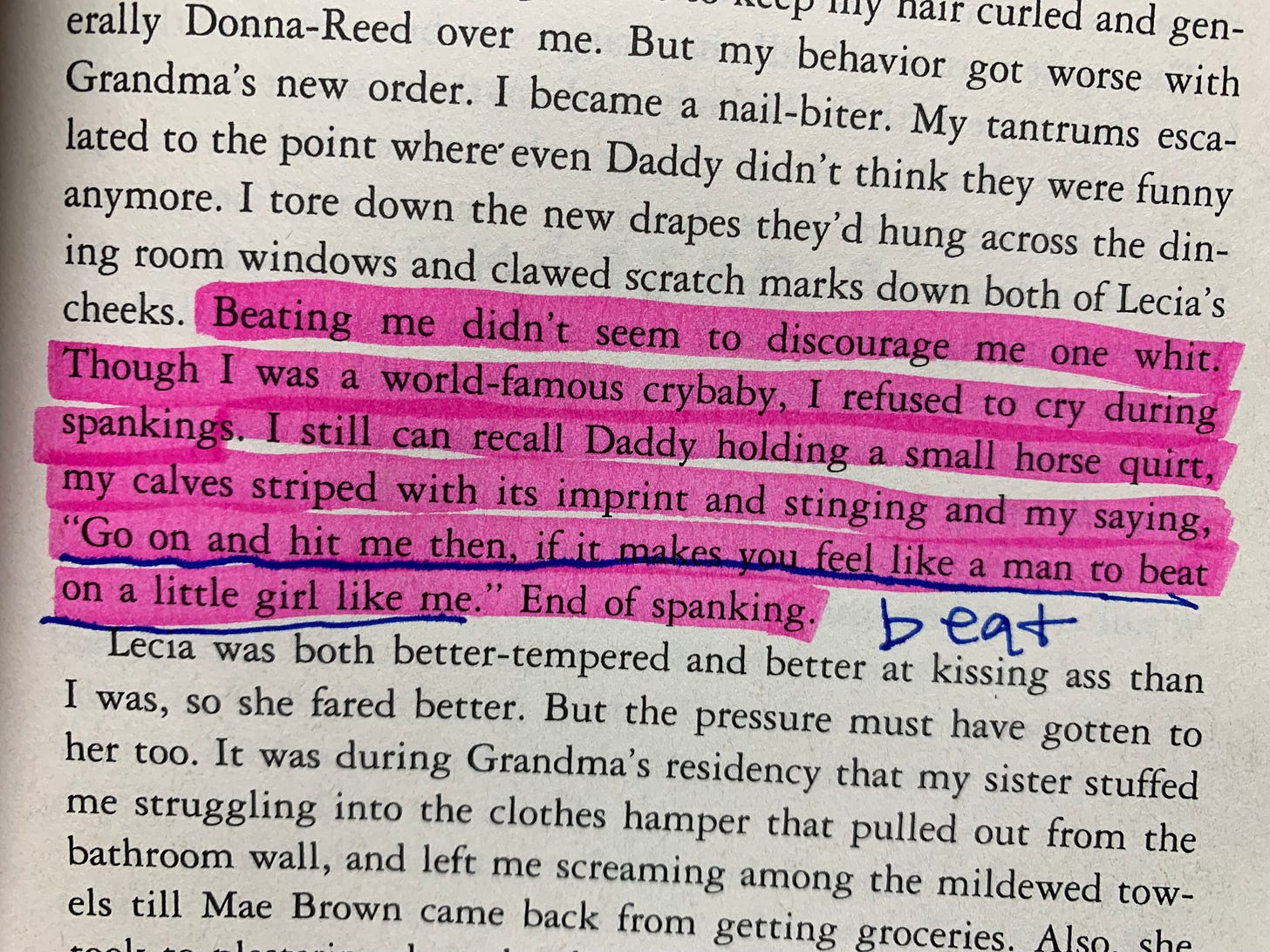

We also get to learn about Karr’s evil, malicious maternal grandma, who gets cancer and lives with the Karr family for some time. The grandma doesn’t like Karr and refers to her often as spoiled and in need of more serious beatings and spankings. (Spankings were normal back then; the grandma wants hardcore beatings to happen.)

Grandma’s cancer spreads and they have to amputate her leg. She gets a fake leg and this leg is a metaphor for the grandma’s tyrannical, detached, unkind nature. (The fake leg reminds me of a Flannery O’Connor short story.) Grandma is mean; she smells. She tells a child Karr that she has two half siblings she didn’t even know existed. (This turns out to be true. In the end Mom married seven times and had multiple kids with several men. Mom also lived for a while in Greenwich Village, Manhattan, in the 1940s, when the Beats were there, as a working painting artist. She still loves to paint in the 1960s and dreams of one day returning to New York.)

Eventually, during a rare family road trip from their tiny Texas town (“the asshole of the world,” Mom calls it) northwest to Colorado en route to Seattle, Washington, Mom decides—after grandma finally dies she’s received a huge unexpected inheritance from Grandma—they need to stop in Colorado Springs and buy a cabin, which they do. They never make it to Seattle. They buy a cabin in the small Colorado town and stay there. Eventually Dad and Mom decide to divorce. The sisters have to choose: Daddy in Texas or Mom in Colorado. They decide to stay with Mom in Colorado if for no other reason than to avoid the blunt horror of Leechfield.

During this time Mom goes nuts, drinking every single day, often to blackout. One day she rubs lipstick all over her face and the mirrors in the house and then pulls everything she can from the house outside and starts the massive pile on fire. She starts dating men, including an evil prick named Hector. Several times Hector and Mom go out of town, to Mexico, leaving the sisters with sketchy family members who make the kids feel deeply unsafe. (Twice Mother had tried to end all their lives by crashing purposefully on the road while driving; once she jumped out of a moving car.)

One day, alone with Mary, age eight, Hector, in a shocking and very descriptive scene, walks into the little narrator’s room, pulls his dick out, shoves it deep into her mouth, clasps his palm behind her head, and shoves in and out until he cums. Karr experienced an explosion of emotion while simultaneously retreating deeply into herself and trying to extinguish her very existence. She tries to become nothing, a black total void of emptiness. Filled with shame and guilt, she vomits after the episode and, when he rubs her back gently and tells her she “did a good job,” she even feels ever-so-slightly vindicated, even as she knows what happened was wrong wrong wrong wrong wrong.

After this—among Mom’s frequent violent episodes and gestures towards suicide—Mom pulls a gun on Hector. Not because of what happened with Mary—she tells no one about that—but because Mom has lost control; her clinical depression, self-loathing and terrible alcoholism have taken hold. Mary throws herself onto Hector trying (insanely) to protect him from the potential bullets. Lecia joins. Mom’s eyes were half-open, empty and vacant. Murder sits in those dicey eyes. Mary manages to sneak out of the house and run to the neighbor who follows her back. In a blind stroke of luck, Mom doesn’t end up shooting the shitty, terrible Hector. (We kind of wish she did.)

Lecia calls Daddy in Texas and explains that he needs to fly them out to him. They need to get away from Mom’s madness. He agrees. Mom accepts this but forces them to be curried by one of her wild bar flies—I forgot to mention, with the inheritance after purchasing the cabin she buys a local bar a little further west in Colorado, where they then move—a faceless drunk named Joey. Joey somehow manages to get himself and the two little girls on the wrong plane and, somehow, they end up in Mexico City of all places. He’d lost his wallet on the plane so the authorities take him away but the girls are let go. (This is 1963, remember.) The girls via several large and small planes and a bus finally make it home to Daddy.

In a dramatic scene towards the end, Mother shows up in a canary-yellow Karmann Ghia sports car with Hector to the house in Leechfield. They’re there—ostensibly—to pick up a bunch of her stuff, mostly dresses and other clothes. The sisters watch as Mother and Hector walk into the house—Daddy says nothing—going in and out to the car and back. All seems okay (unlikely) until Hector mouths off to Mother while getting into the car. This sets Daddy off—he still loves his ex-wife—and Daddy beats Hector to within an inch of his life. Eight-year-old Karr admits she enjoys this thrall of vapid violence. (Can’t fully blame her here.)

Mom, of course, comes back to Pete Karr. She drives Hector to the nearest ER and then returns to her ex-husband. They remarry. That is that. All four of them—Mom, Dad, Lecia and Mary—have somehow, incredibly, survived.

I wish the memoir had ended right there. At page 270. It would have been as close to a perfect memoir as one can get to, I think.

But instead Karr then pivots to 1980, when she’s 25 living in Boston. We get 50 more pages, which for me were dead boring and wholly unnecessary, all about her having gotten out of Leechfield on her own, finally, at 17, going to a small liberal-arts private college, and moving to Boston. More so it’s about her Daddy’ stroke and terrible hand-trembling alcoholism. She drinks with Daddy a few more times at the American Legion like the old days. Daddy even beat up an aggressive cowboy during this time, right in front of her. They never speak of What Happened in Karr’s past. Daddy is a Texas man who came of age riding the rails during the Great Depression: Emotions aren’t his wheelhouse.

But Karr does eventually open the door to the past with her mother. It takes much alcohol and a lot of prying and pleading but finally Mom opens up. The Big Reveal is that Mom did in fact have two previous kids, half-siblings to Mary and Lecia, and she lost custody of them and they faded out of her life. These two ghost-children were what ultimately drove Mother’s madness, depression and alcoholism, at least according to the old woman herself. Mary and Mother feel vindicated; the lies have finally been lifted, the light of the truth has filled the room.

But of course we’re still left with a seriously damaged Karr, and the story ends there. You have to read Cherry and Lit to get more of the story. (But Mary Karr’s own divorce, single motherhood and dating of David Foster Wallace who was allegedly physically and emotionally violent tells us what we need to know; how could Karr have not been damaged from her searing, absurd childhood?)

For me, the memoir ended at page 270. The final 50 pages were, more or less, extra and, basically, a waste. She told it all in the real-time story. In my opinion it would have been a stronger memoir without the 1980 material. I never felt connected enough to Pete Karr or the crazy Mother character. They were side stories that drove the engine of the “plot,” but the story, always, for me, was the first-person “I” narrator; the child-victim that was telling us this harrowing story.

But as for those 270 pages: Wow. Double-Wow. Triple.

Karr is first and foremost a poet so you can imagine her bending of language, diction, syntax. Each word feels necessary and precise, there for a very specific reason. The lines are clean but also not overly MFA-polished like you see in today’s writing. Chisel and hammer but not surgical instruments on the molecular level. The voice reaches its arms out and chokes your throat. It’s honest, straightforward and unsentimental. She feels deeply into nuance and complexity, making herself, Lecia and most crucially her parents not binary caricatures or all evil or all good or victims or oppressors but rather does what good fiction writers do, too: Shows us their ultimate, fragile humanity. She shows us her Daddy and Mother’s good, soft, loving and kind sides. And she shows us their terrible, alcoholic, awful sides.

She shows us how the child Mary Karr is both a victim and yet feels complicit in her own victimhood. She does what she needs to do to survive physically, spiritually and emotionally. She doesn’t see her parents as “bad people” but rather as flawed, deeply wounded human beings who have their own trauma which they sadly cannot husk off themselves. In the desiccated landscape of Leechfield, as in the desiccated landscape of her childhood havoc, child Karr only wants to be loved. Not even “seen and heard,” as people say today. Being seen and heard would have been far too much to ask for. Just love. Basic, easy love. And she does get love from her parents, even if it comes in a very twisted, misshapen form.

Her parents aren’t good people nor bad people. They’re profoundly broken people. Karr’s true triumph is having survived to tell the tale, an becoming successful in life doing what she loves best: Writing. I’m supremely grateful for this memoir. Rereading it really did feel like reading it for the very first time. I somehow missed so much the first go-round. Maybe I wasn’t ready to receive it the first time. But I was now.

Everyone should read this book. There are lines—it was published in 1995, her first book, when Karr was 40—which come off to a contemporary eye as “racist.” (Texas in the early 1960s, what do we expect?) There are scenes which seem almost impossible to read, like her childhood rape and the brutal molestation at the hands of her mother’s new husband, Hector.

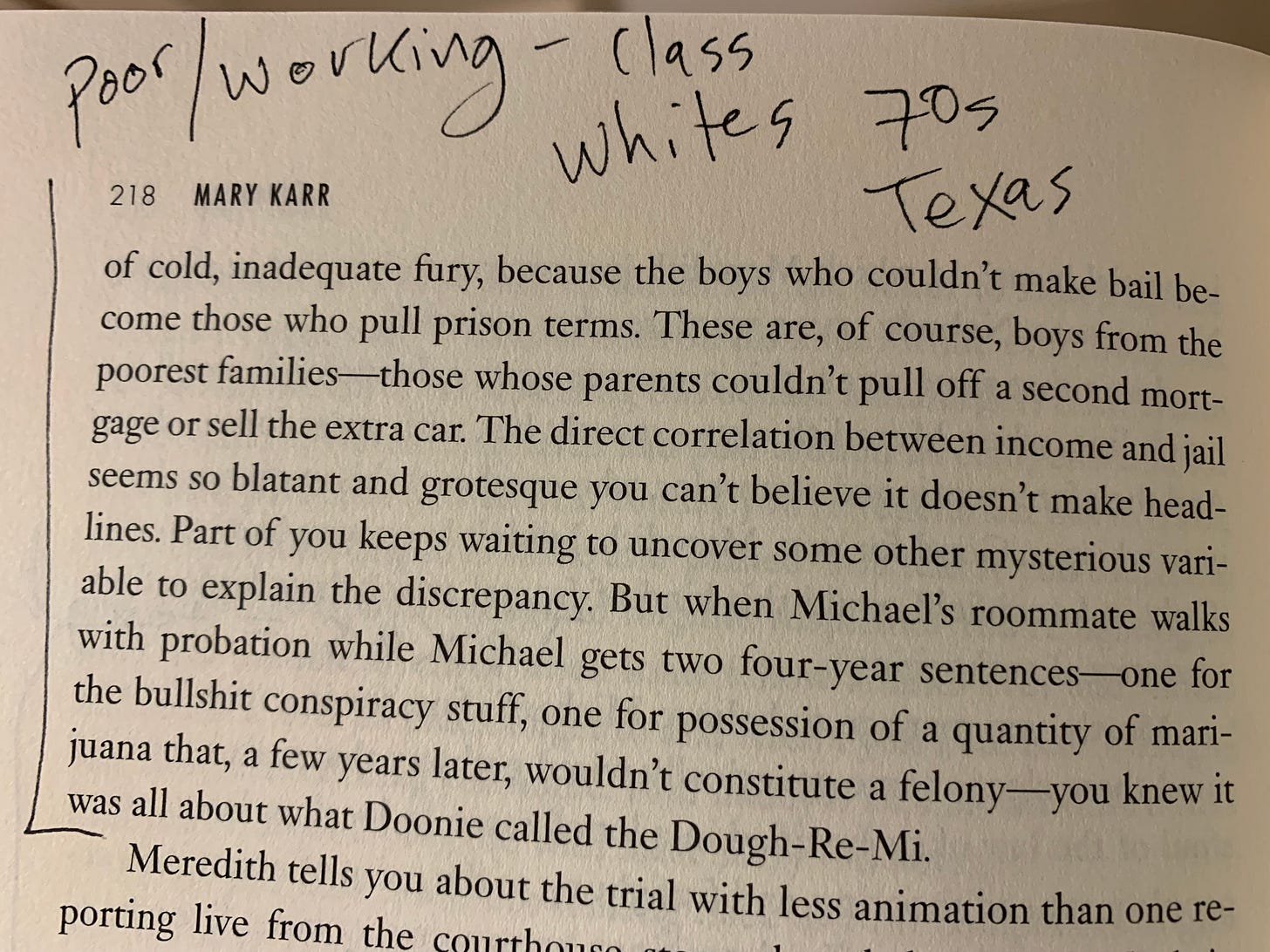

There are moments which feel so grotesque and over-the-top that you can’t even believe it. It does feel like a 1960s female version of JD Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy, which I wrote about HERE. The white trash. The alcoholism and drugs. The working-class life. The local poor white folks on welfare. The sexual retrogression. The male-female roles. No one gone to college in the family minus Mom. It was from Mom Karr got her love for reading, writing and creativity.

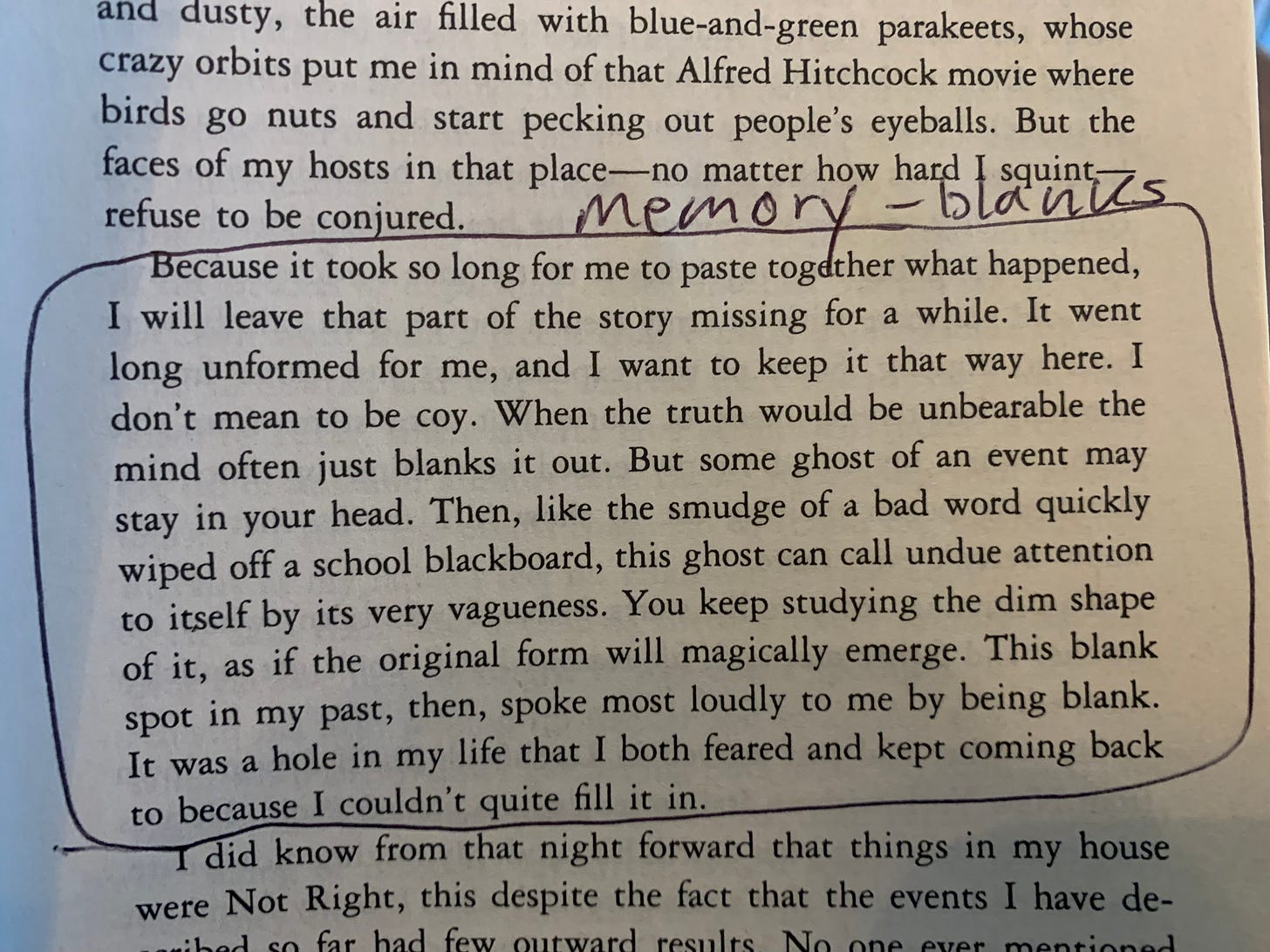

In the end, the gem of this memoir is Karr’s incredible honesty. She doesn’t flinch. She tells it like it is. When she doesn’t remember something for sure, she tells us so. When Lecia recalled it differently, she adds Lecia’s side of the story. When she’s unsure exactly how something went down she includes that lack of knowledge.

For a woman writing in 1995—thirty years ago now—she has the bravest pen in the world.