More Thoughts on Vladimir Nabokov (Part I)

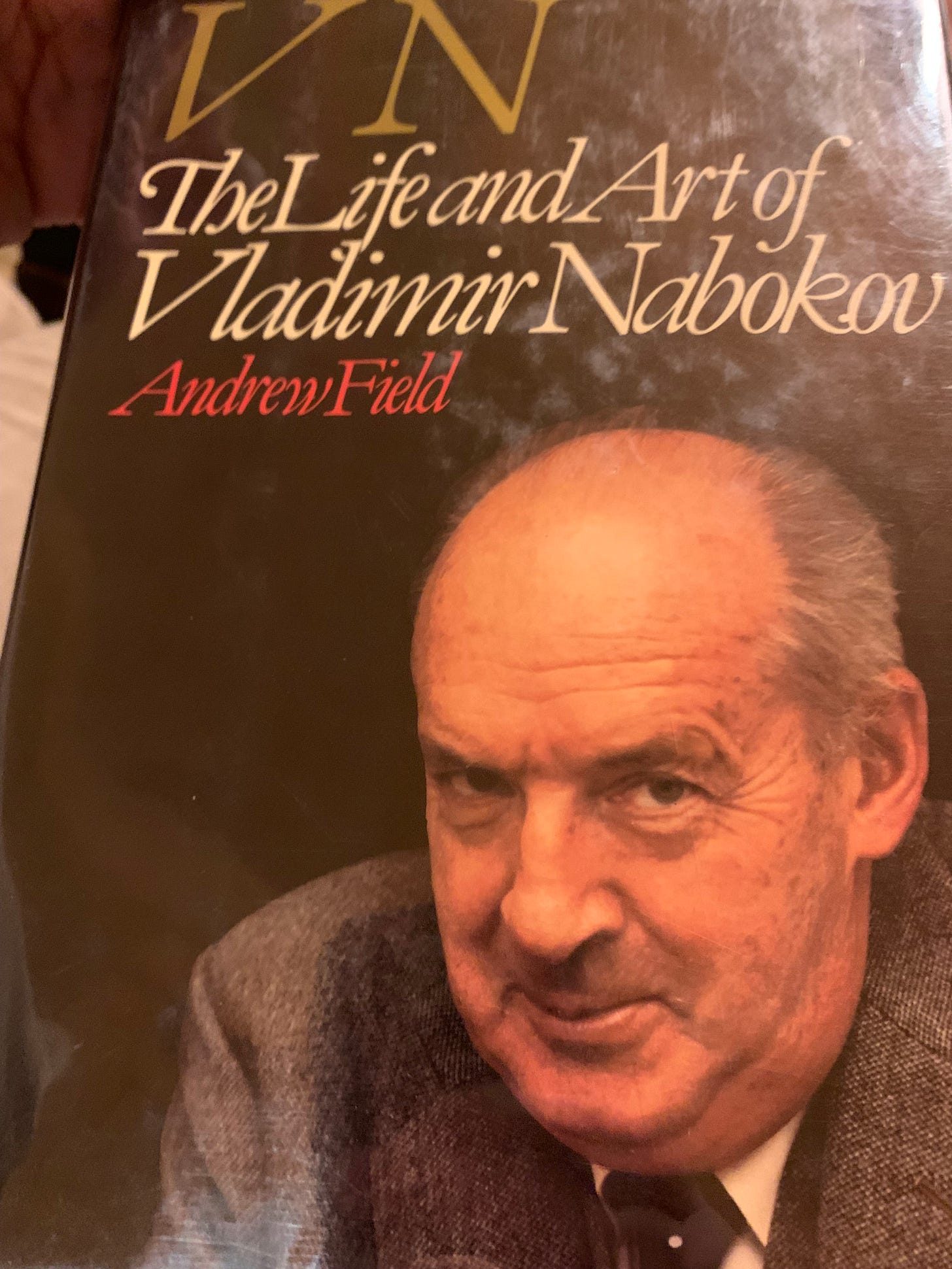

Andrew Field’s 1986 biography, VN: The Life and Art of Vladimir Nabokov

*Want to read all my content? Consider going paid for just $5/month or $35/year. I publish both free and paywalled content, and you won’t want to miss anything. Please also consider sharing, re-stacking, recommending, etc.

**I have a new stack exclusively about writing and editing, WRITING AND BOOK EDITING: THE PROCESS. Click here for that. (Free so far but would greatly appreciate paid subs for support!)

~

First, read my older post on Nabokov’s collected letters here.

I go through phases with reading. Sometimes the books I explore are random, depending only on time, chance and luck. Other times I read one author and then go down a rabbit-hole. Or I become literarily obsessed with an author, an idea, a time-period, you name it. Everything from politics to literary eras to styles of writing, etc.

Right now I’m obsessed—I can’t exactly explain why—with Nabokov. I’ve always found him tantalizing, which on one hand is ironic since I usually generally do not enjoy reading and certainly don’t enjoy writing what I’ll call “poetic prose.” I’ve always organically been more in line with the stylistic lineage of, say, Hemingway, Bukowski, Raymond Carver, Denis Johnson: You know, that diamond-tight, clipped, crisp, almost reportorial style. Dostoevsky versus someone like Nabokov; Dostoevsky being stylistically a very simple, basic writer, but creating books which are beyond profound, versus the stylistic pyrotechnics of someone like, say, David Foster Wallace, Susan Sontag, Michael Chabon.

For me the pyrotechnics have always felt more superficial and clever and I’ve always been more interested in depth, honesty and clarity; genuine communication from writer to reader. (Read my essay on Orwell and his Politics and the English Language here.) Tell it like it is, but tell it deep (not slant, per say).

And yet, Nabokov seems to stand on his own, in his own category, as did Pushkin, Turgenev, Gogol, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky (who Nabokov claimed to hate but also borrowed from).

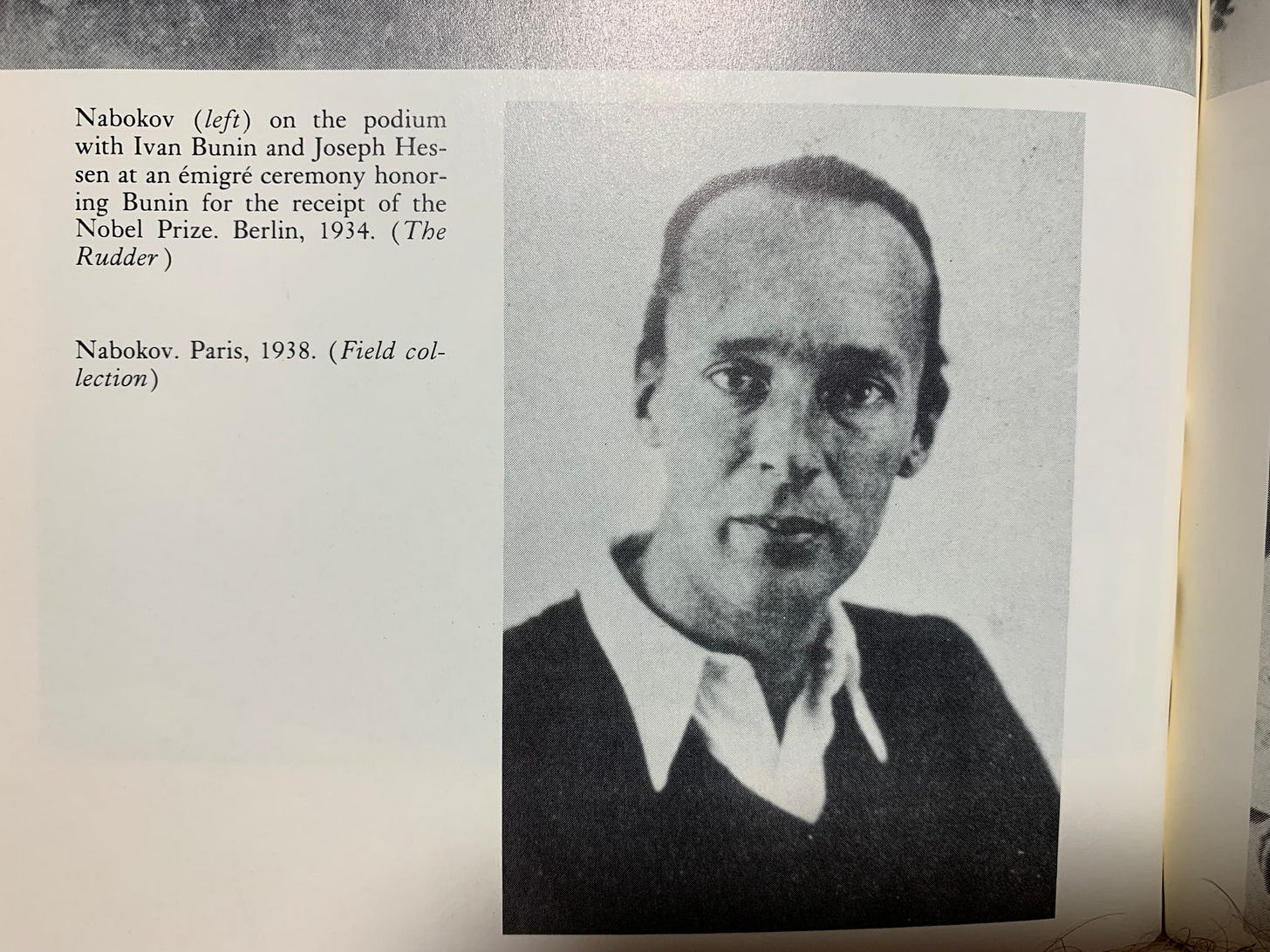

Nabokov led a very interesting life. Born in 1899 in St. Petersburg, Russia—the same year as Hemingway, I might add—dead in 1977 in Switzerland, his 78 years of existence were one of fleeing, emigration, refugee status, great wealth, semi- poverty, and golden artistry. He was born into profound wealth. His father—V.D. Nabokov—was involved in radical politics (he was a Kadet, interested in western classical liberalism, anti-Czar protestation, and pro-constitutionalism) and was also a literary man: He wrote himself and was founder and editor of one of the most important émigré literary newspapers in Berlin, The Rudder. Mom came from a wealthy mining clan. (Most of the Nabokovs down the line had attained wealth by marrying wealthy women and attaining incredible dowries.) Nabokov’s father and grandfather had both at different times worked with and under Czars.

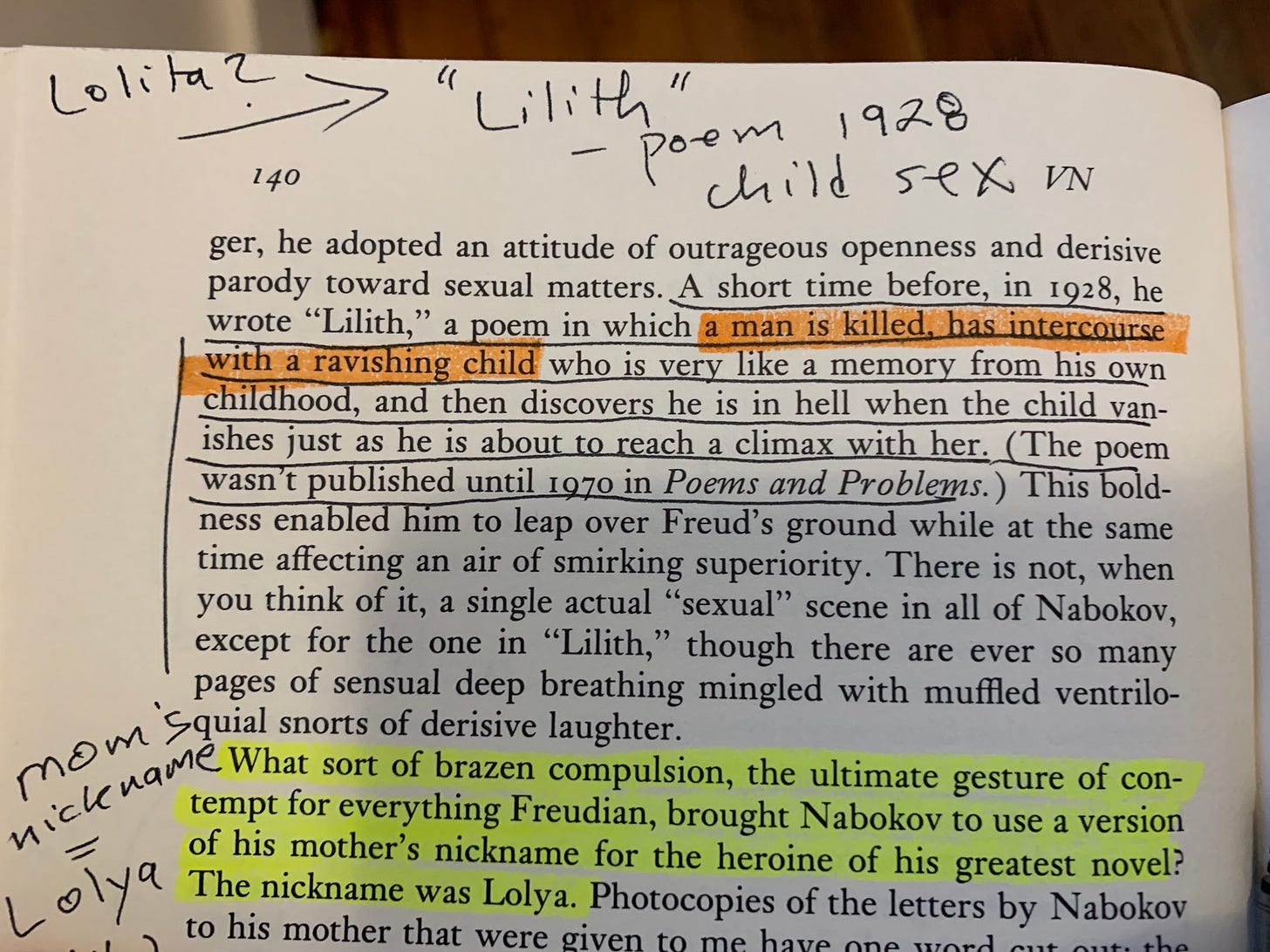

Though coddled beyond normality—the family had 50 servants and a limo—Nabokov was also probably (but we don’t know for sure) molested by his mother’s brother, his uncle Ruka. Nabokov’s grandfather had created a family legend when he married a 17-year-old girl (he was 33) in order to have a sexual affair with the teenage girl’s mother. And Nabokov’s teenage grandmother slept around…a lot. Possibly even with Czar Nicholas’s brother Konstantin. The grandfather’s dalliances certainly came to mind when writing Lolita decades later. Instead of the older man marrying the younger woman to get to the older woman (the older woman’s daughter), the novel became the older man marrying the older woman to get to the younger…girl (the older woman’s daughter). (Taboos were also something Nabokov enjoyed playing with, like a cat with a mouse.)

When the future genius author was only 16 he inherited 2,000 acres and a few million dollars when his uncle Ruka died. The molesting uncle had left everything to his “favorite” nephew. At 16, Nabokov was rich. He had his own money. It was around this time that he self-published his first collection of poetry, using his new inheritance. The collection was largely mocked. People resented the kid’s easy money and easy life. One teacher at the Teneshev School, where he attended in his teens, asked him to at least be dropped off in the limo a block away so as not to embarrass the others.

But everything changed when, in October, 1917, the Bolshevik Revolution occurred while World War I was still going on. Lenin and Trotsky were suddenly in power. They’d been trying since the failed Decembrist Revolution of 1905 which had created the first Duma and a semi-parliamentary system but had been in practice more or less a joke; the Czar could (and frequently did) dissolve the Duma when he felt like it.

The Nabokovs weren’t safe. No one was, really, but especially because of his father, who was a political Leftist radical, someone who wanted liberalism and democracy, not autocratic central planning as Lenin proposed. The Nabokovs were anti-Czar…but also anti-Communist.

First they fled from St. Petersburg to the Crimea. They stayed their 18 months and V.D. even worked within a provisional émigré government there. Then they sailed for Berlin. Nabokov stayed there only briefly and then attended college in Cambridge, in England. Some accused Nabokov—and more than once—of being a coward because he chose to flee instead of fight during the revolution and subsequent civil war that soon erupted in Russia, pitting the White (anti-Bolshevik) Army against the Red. Perhaps. He was eighteen years old when they fled to the Crimea, and from a very wealthy upbringing. He feared for his life, as many back then did. It wasn’t a cause he felt the need to die for. And yet, all his life—living in exile—he nurtured the honeyed, rich nostalgia of one day returning to Russia. (He never did.)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Michael Mohr's Sincere American Writing to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.