My Personal Philosophy

The Art of Risk

~

Today’s essay is part of a series (we’ve been doing these for over a year now) by Latham Turner, Bowen Dwelle, Michael Mohr, Dee Rambeau, and Lyle McKeany and

. This week, all of us explore the roots of our personal philosophies. Other series’ have covered: trust fatherhood recovery work and home.Playing it safe—whether in work, life, travel, convention, opinion, love or writing—has never been my thing. It’s just not who I am. Like all of us I am a manic mix of my parents’ genes, my father’s arrogance, political intensity and brain; my mother’s creativity, love for writing, intensity and search for control. But I also, like all of us, am just that strange mysterious “me.” And in that “me” is a man who, if you were to measure the whole of my existence up to this very point right now as I write this sentence, has learned how to live by hardcore trial and error.

Growing up I was always attracted to literature. How could I not be with an author mother who possessed a large library of classic tomes, a novelist uncle who also had many books, and an early penchant for reading as escapism, a ripe imagination, and the penning of ponderous poetry from around the tender age of eight?

I don’t recall exactly when I started reading philosophers—nor who the first ones were—but my hazy vague recollection tells me sometime probably in my mid or later twenties. Nietzsche. The Existentialists, from Kierkegaard to Dostoevsky to Sartre. Voltaire. Descartes. Even a little Kant and Hegel, that 19th century German philosopher whose work is eminently complex and abstract. I also read some Plato (I tried several times to get through The Republic but finally gave up), Aristotle, Jean-Jaques Rousseau, John Stuart Mill, Henry David Thoreau, Schopenhauer and many others.

In addition to these foundational 19th and 20th century philosophers (as well as classical Greek thinkers) I also devoured books—this was later, in my thirties—by writers and thinkers such as Norman Mailer, Henry Miller, George Orwell, Earnest Becker, H.L. Mencken, Alan Watts, Christopher Hitchens, and many more. These writers weren’t philosophers per say, not technically, but they clearly all possessed various philosophies, and of course all or most of their ideas were deeply steeped in the philosophers I mentioned earlier, just as theirs were steeped in and sometimes adding to and/or pushing back against some of the earlier philosophers which came before them, all the way back to the pre-Greeks and then the founders of traditional Western thought such as Aristotle, Plato, Thucydides, etc. It was, just like literature and painting, a long, nuanced, complex tradition, dialogue, conversation.

If I had to pick any of these people who I felt described my own personal philosophy to this point in my life currently I’d choose a mixture of Kierkegaard, Norman Mailer and Henry Miller. Kierkegaard for his assertion of faith or a “higher power,” Mailer for his warrior-like “metaphysical existentialism,” and Miller for his belief in the self, the righteousness of the individual going against the grain, his inherent contrarianism, and his direct life experience lived as a unique human soul fighting for spiritual sustenance in the form of true and total freedom psychologically and in all other ways.

That last one describes more or less where I’ve landed now.

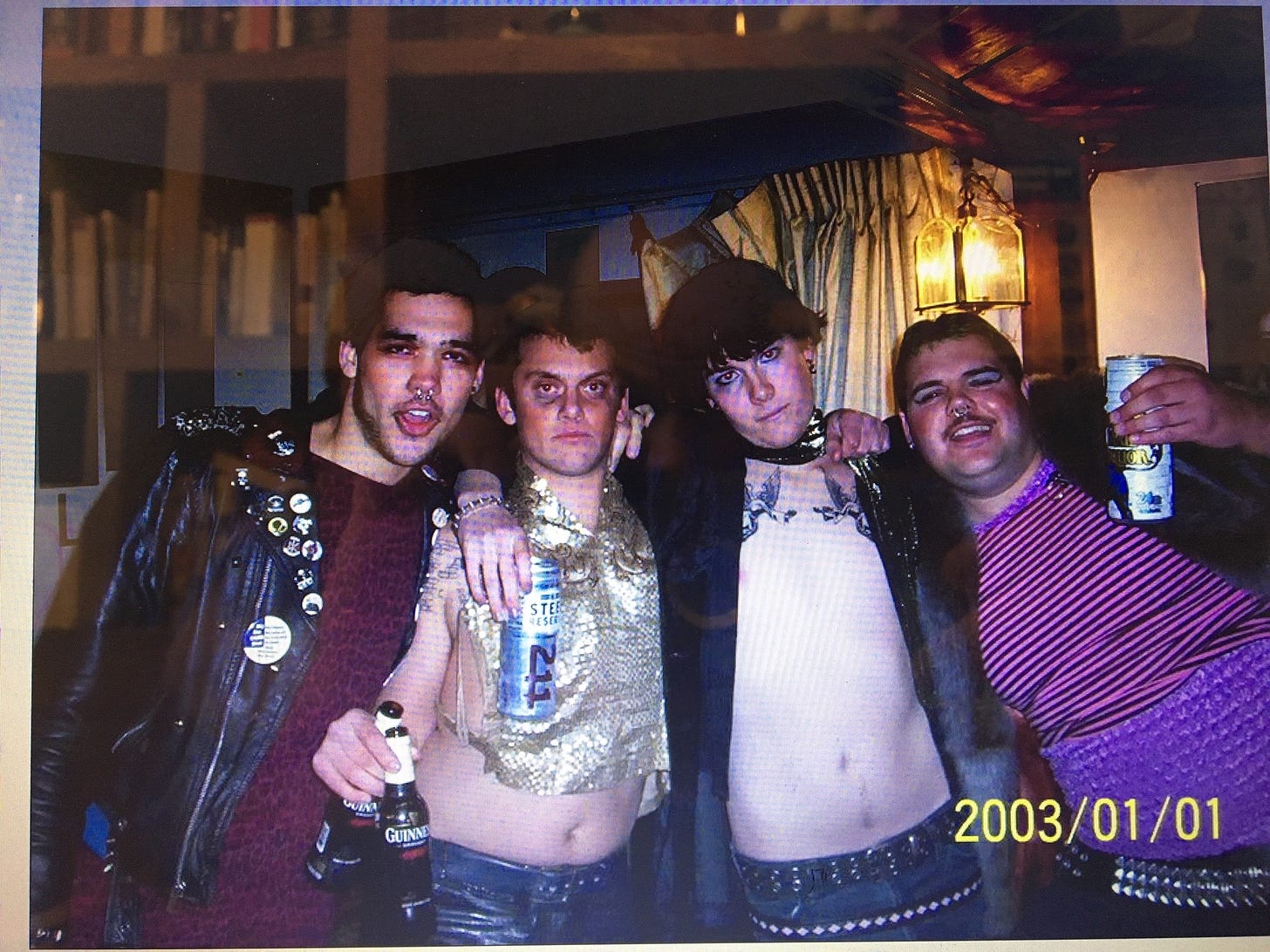

Coming from a very conventional family who pulled out all the stops, got all the degrees, worked the typical jobs and believed the usual upper middleclass things, my warm blanket of safety as a teen arrived in the typical form of rebellion. Not just rebellion, though; harsh rebellion. I felt like a soldier remanded to war. I was fighting an existential and spiritual battle against the forces of parents, convention, wealth, privilege and safety. I wanted, of course, exactly the opposite of all these things. *(Read my autobiographical coming-of-age novel about this period of my life by clicking here.)

And so, like most people to varying degrees, I found myself on the road to contrarianism and rejection of my parents’ bourgeoise values. This was how I “found” myself. (It took a while.) Jung writes of “individuation,” the healthy breaking free of the emotional strings of the parents, discovering your own ideas, values, philosophy, likes and dislikes and ultimate Self separate of your parents. (Opposition, then, is what we might call the “infantile stage” [thank you, Freud] of this finding of the self.)

After blasting through that hard stone and rock, tunneling under the mountain that was young adulthood (I barely survived high school), I decided that, in my early and middle twenties my goals would shift a little, though still run on the rich, black gasoline of anger, self-resentment manifested outwardly (because why blame yourself when you can always blame others?) and the deep stench of the denial of alcoholism.

But by 27 I hit a spiritual and emotional bottom. No matter how much I drank, how much sex I had with random women, how many times I hitchhiked around America, how many books I read or poems I wrote, I simply couldn’t shake this visceral feeling of failure; this sensation ripped and licked and popped like wild orange flames in the deepest part of my soul. It was a fast-spreading metastasizing cancer that either needed to be removed or else it would kill me.

And so, I got sober. This was 2010. I was 27.

Since then, the past 14 years, my philosophy has been a mixture of my past and the future I day by day grew into. The man I am now. And that philosophy is something like this: The Art of Risk. More specifically: Life is short; you could be dead tomorrow, next year or in five minutes (or in 50 years) and so, as Camus said in The Stranger, we’re all technically “condemned to die.” Ergo, why play things safe? Why not do what you want, when you want and how you want?

Now, there’s been amending to this personal-spiritual constitution over the years as I’ve matured and grown older and been repeatedly smashed up against the thick cliff rocks of reality. For one thing: I can’t risk everything without any regard for others in my life. For example, I have a wife. We have three cats. I have to work to make money. Ergo, we can’t just up and sever our ties tomorrow and travel the world. (I wish we could!) That said: We are working on moving to Spain in spring. This is something we both value and want to do. We’ll travel once we’re in Spain, but we’ll have a home base for our cats.

I’ve bumped up against this idea of risk many times, too, in my writing, which is most often heavily autobiographical, though not always and not entirely. I have angered a few people close to me in my life over the past 15 years when writing about them. My mother, exes, a painter I had a relationship with in New York who played a central role in my memoir, which you can read here. (We worked it out. I changed all names. Etc.) A good author friend of mine who didn’t like the way I portrayed her on the page.

So this is a delicate thing, this “art of risk.” When it comes to writing I have for a long time, up until fairly recently (say the past 3-5 years) generally felt like anything goes, in the Henry Miller sense: I reserve the right, as an author, to write about whatever I want, whoever I want, in whatever way I want, etc, provided that I change all names and maybe tweak a little here, a little there for the basic sake of pseudo-camouflage. This has resulted, at times, in anger. How could it not? I totally understand why someone would feel this way.

Writing is tricky, especially autobiographical and memoir writing. For one, memory is deeply suspect and slippery. Science has shown us this. For two, everything I write—and everything you write—is of course naturally biased and one-sided. We can’t help this; it’s a human trait we all possess. (Read my essay on writing and bias here.) Ergo, I see the real people in my life from a particular, unique perspective, just as they see me from the same. The difference, often, is that I write about myself and others and publish that writing both online and in print; usually, with some exceptions, they do not.

To further complicate things and perhaps add insult to injury: I have never myself had to be in the literary hot seat; I have never had to read writing from anyone else about me. (This truth actually surprises me, but I am simultaneously glad.) Therefore, there’s a bit of an intrinsic lack of understanding and empathy on my side, because I don’t fully comprehend emotionally what that experience might be like for the person reading about themselves from someone else’s perspective (sometimes fairly judgmentally).

And yet: What can I do? I am a writer, and I do write autobiographically, and I am infatuated with a sort of anthropological study of myself and other human beings around me. This is what writers do; they observe, translate ideas and metaphors from the world and people around them, and write these things down with some sort of voice and style, attempting, if they’re any good, to put down on the page what most only feel in their solar plexus.

This is not an easy task.

Playing it safe—whether in work, life, travel, convention, opinion, love or writing—has never been my thing. It’s just not who I am. Like all of us I am a manic mix of my parents’ genes, my father’s arrogance, political intensity and brain; my mother’s creativity, love for writing, intensity and search for control. But I also, like all of us, am just that strange mysterious “me.” And in that “me” is a man who, if you were to measure the whole of my existence up to this very point right now as I write this sentence, has learned how to live by hardcore trial and error.

I have rarely done things the simple way in my life. (Ask my mom.) The path of least resistance has never been my modus operandi. I actually prefer struggle, prefer to be thrown off the cliff into the symbolic abyss of the Great Unknown. I suppose a kind interpretation of this tendency to take risks and make my own life harder can be summed up thus: With great struggle comes great reward.

When I was young people often told me, You’re entering a world of pain, or asked me, Why do you do everything the hard way? At the time I didn’t really have a good answer. But now I do: I did and do things the hard way because it’s fundamentally who I am. I struggle because struggle feels real to me; authentic, genuine, raw and true. And raw truth—gritty life experience—has always felt more true to me than anything else, including convention, safety, the well-worn middle-class path, and even books.

There’s a reason I hitchhiked all around and even across the United States; why I took Amtrak across the whole country half a dozen times, aimlessly; why I worked a zillion jobs and quit many of them a week or a month in; why I couldn’t keep a relationship going for longer than a couple months in most cases (a few exceptions); why I drank the way I did; why it took me 11 years and seven colleges to finally get a bachelor’s degree (in writing) at the age of 30; why I rejected the MFA after being accepted weeks before the start of class; why I never owned a TV; why I rejected my parents’ values out of hand; etc.

The reason was that I wanted—no, needed—to do things my own way. It wasn’t really about being “unique” or “different” or even, as I thought back in my teens and very early twenties, about “being an individual,” but rather about discovering my deepest sense of self in the form of gaining life experience. In other words: Taking risks, doing things my way, allowed me to understand myself and the world around me. I got knocked up a lot, especially from the decade of blackout drinking from age 17 to 27, but, somehow, I managed to survive and then eventually flourish.

Which brings me again to now. Almost 42. If you look at my life on paper it seems pretty standard at this point: Married, three cats, freelance book editor and dog walker, living in Portland. Etc. But if you lift the hood just a tad you’ll see that this engine runs on its own power. It doesn’t require the oil and gas most cars do. We’re working on moving to Spain so we can experience life abroad, getting the “outside America” experience. We discuss moving to Asia (probably Thailand or Japan) at some point in the future when we’re cat-less. (Hopefully not for a long time!) We sold my house in the Bay Area and, more or less on a whim, bought a multi-unit here in Portland which we’re now renting out so we can move to Spain.

My point is that, even now, at almost 42 years of age, I’m still more or less living life on “my terms.” I got married not out of any sense of pressure—for a long time I thought I’d never get married or if I did I’d be in my fifties—but because of genuine (and surprising!) love. It still shocks me how many couples get married (even in contemporary times) for reasons other than love: Money, taxes, stability, practicality, location, moving countries, safety, loneliness, fear, societal pressure, etc. I knew I’d never get married except for one reason, and that reason had to be sure: Love.

The point of all this is basically to say: Everything I’ve done I’ve done because my own metrics have been met, not because somebody or some institution or societal convention told me to. And like I said: This hasn’t made for an easy life. I can’t say (ask my wife) I’m exactly the “happiest” person you’ll ever meet. There are so many things I still want, like traveling the whole world, which, right now, for a variety of complex and realistic reasons, I can’t do. But I found a woman who largely wants the same things I want, and who also pushes back on some of what I want, pulling me uncomfortably back into reality when I’d rather go full-bore. (This push/pull has been a struggle and also a beautiful thing.)

Kierkegaard wrote a lot about Faith (for him in Christ) leading him to a Higher Purpose. Dostoevsky wrote often about the lonely, isolated man making his way in the world on his own, forging his own path. Camus wrote about suicide and death and making your own choices as a method against complacency. Nietzsche wrote about the “Uber Mench,” aka the Superman, who transcends the weakness of the frail man and supersedes that level to become something bigger, greater, stronger.

All of these ideas have influenced me over the decades. But living my life the only way I know how—on my terms with my own voice and actions—has always been my guiding North Star. I’ve never accepted other people’s experience as a priori good for me and my life.

This has brought struggles, heartbreak, tension, the law, violence, alcoholism and so many other little terrors into my life. Yet it’s also brought profound love, great joy, transcendent experience, self-reliance, self-love, forgiveness and acceptance.

As we all are, I am still, of course, a work in complex progress. I’ve done many things in the past I’m not proud of. I’ve made a whole hell of a lot of mistakes. I’ve hurt myself and the people I love deeply at various times. I’ve even questioned my own motives and integrity at times.

But I keep walking that path, following the full moon of my own choices which draws me on. One day, my life, as all of ours do, will expire. And then it will be for others who knew to judge whether I was good, bad, or some kind of mixture of the two.

Until then, as Robert Frost famously quipped in his poem, “I took the path less taken. And that has made all the difference.”

~

Check out the rest of the gang’s essays in the series:

You hit on the essential conundrum for the memoirist: how to write into danger zones while remaining mindful of the impact on others. It is in fact an art to do that responsibly. Those ethics are always up for debate, as they should be. But it does seem to me that choosing an alternative path isn't always a choice, and when that's true for us, the best we can do is navigate the consequent risks artfully. Thanks for your insights here.

on your own terms, yes! You've reminded me again of Miller—and that I should read more actual philosophy! You should make a reading list!

btw "per se" not "per say," although the latter is an interesting construction, per se.