For a long time I’ve possessed a fascination with Vladimir Nabokov (1899-1977). I recently ordered his collected letters 1940-77 and I couldn’t put it down.

First, his general life plot was interesting: Born in Russia, he fled during the 1917 revolution and lived in Paris, Berlin, Switzerland, and finally the United States, in 1940—fleeing World War II—where he later became a U.S. citizen.

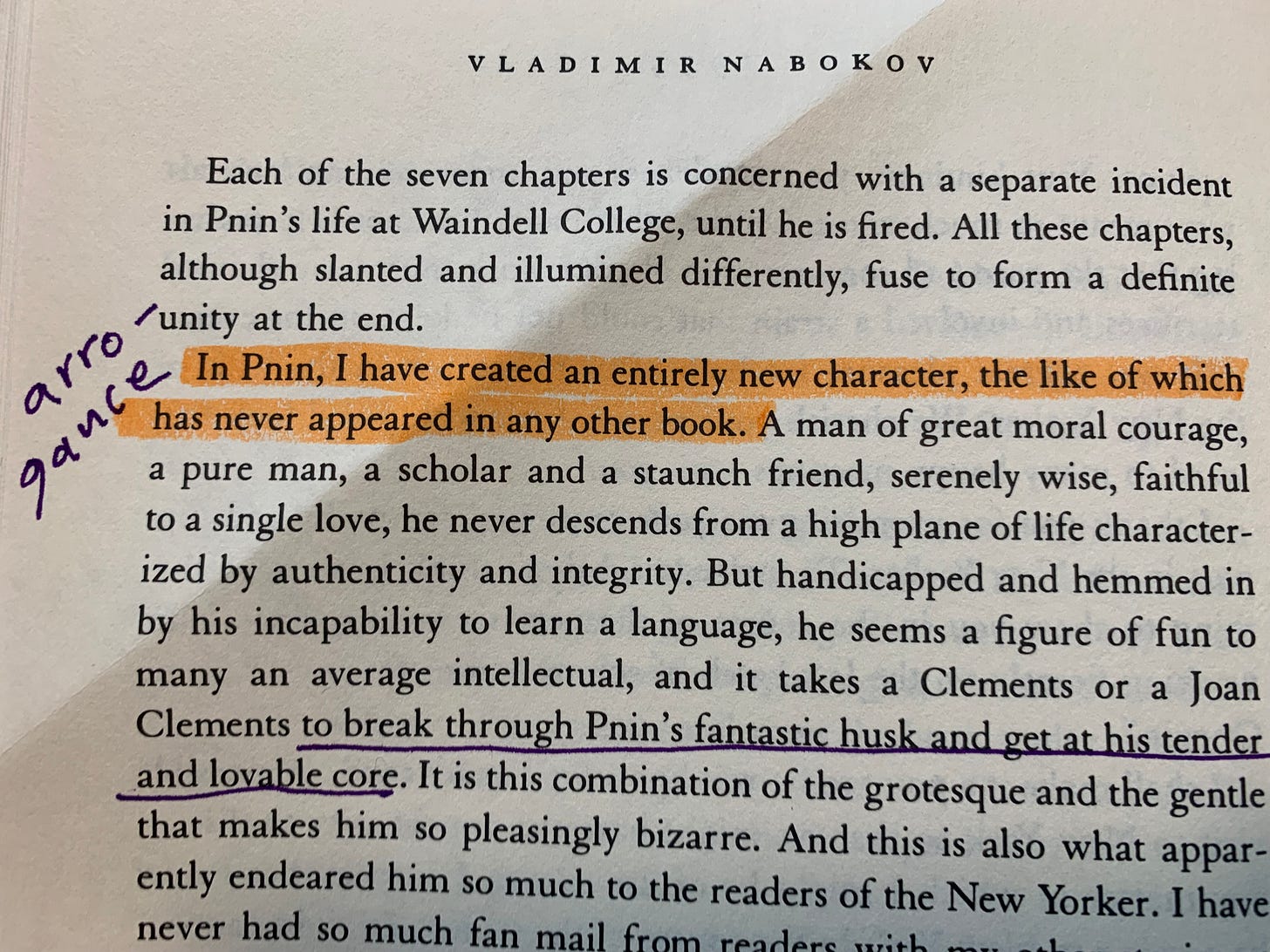

He was clearly a genius. He taught at Wellesley, in Massachusetts, and at Cornell, in both cases usually teaching Russian and European Literature. During these years he simultaneously wrote maniacally and feverishly. Almost always he had multiple books being written at the “same time,” switching from one to the other like a literary lunatic. His letters are rife with commentary on two, three books at a time. How he pulled this off, while also teaching, is beyond me. (Usually when a writer does this he or she is more of the Stephen King variety, penning quick, lucrative, bestselling thrillers, not producing “serious literature.”)

Nabokov was a consummate artist in the vein of Chekhov—who is probably his most realistic predecessor—Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Pushkin, or a writer such as Gustave Flaubert. Combining speed with literary quality is not an easy feat. Ditto moving from country to country fleeing war.

Nabokov also had some of the strongest artistic integrity I’ve ever read of. Whether he was arguing with Katherine White—editor at The New Yorker during the time he often published there in the 1940s and 50s—or else “yelling” at the author or publisher of a bad translation of some Russian author into English, Nabokov pulled no punches. He did not fear being rejected due to his arrogance and sophisticated determination to do things right in his eyes. He told editors, authors, publishers in no uncertain terms when they were, in his view, dead wrong. Sometimes these people caved, other times they did not. He accepted some editorial changes to his work, but usually only minor ones, and he battled fiercely to explain why he rejected many literary and editorial suggestions, usually going literally point by point in his detailed, meticulous letters.

Besides writing novels, Nabokov also penned a memoir—Conclusive Evidence, later Speak, Memory—as well as essays, criticism, poetry (some of his first work taken by The New Yorker) and translations. He translated Anna Kerenina, several books by Pushkin (primarily and most importantly Eugene Onegin) and many others, at first by himself and then later with his son, Dmitri. Often his commentary and editorial notes which accompanied the translations were 200, 300 pages long, at times dwarfing the length of the actual book being translated. The man was detailed, specific and passionate. He ripped bad translations and bad translators apart at every opportunity, explaining, sometimes word by word, how they’d screwed up.

It seems patently evident based on the letters that Nabokov knew he was a genius. He relished in this. His integrity and sophisticated arrogance stemmed not so much from his entitled upbringing—he was born into an aristocratic noble Russian family, his father a liberal lawyer and journalist and his mother was a gold-mine heiress—though certainly that played a role, but more from his clear and obvious intelligence, his sharp wit, his brilliant mind, and his tragically profound writing talent. He intuitively grasped his own worth, both in the literary world and in general. That type of inner confidence and knowing was and still is rare. And he wasn’t wrong to possess and cling onto that sense of self-worth. He was good and there’s a reason his name still circulates today, in 2023.

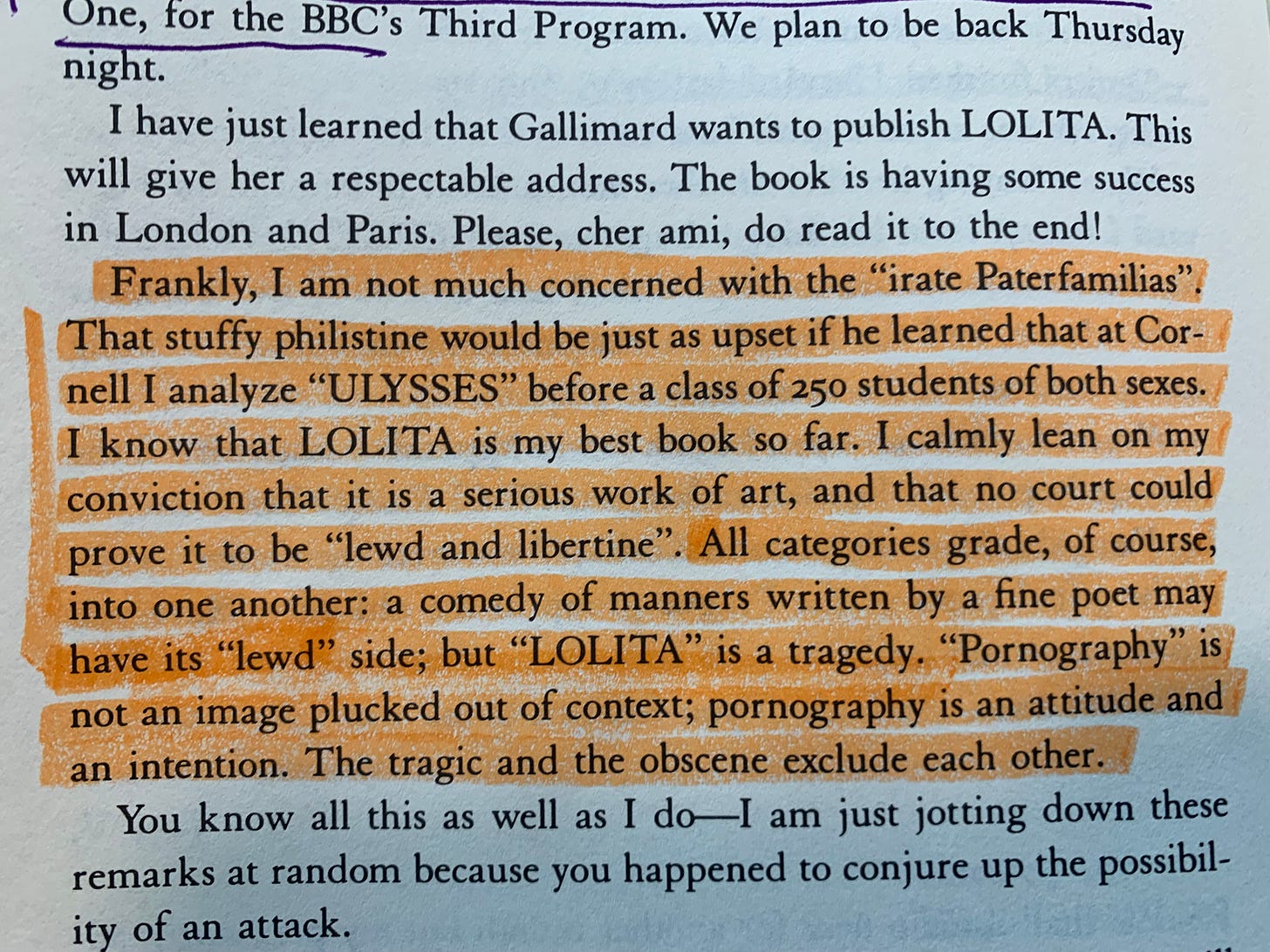

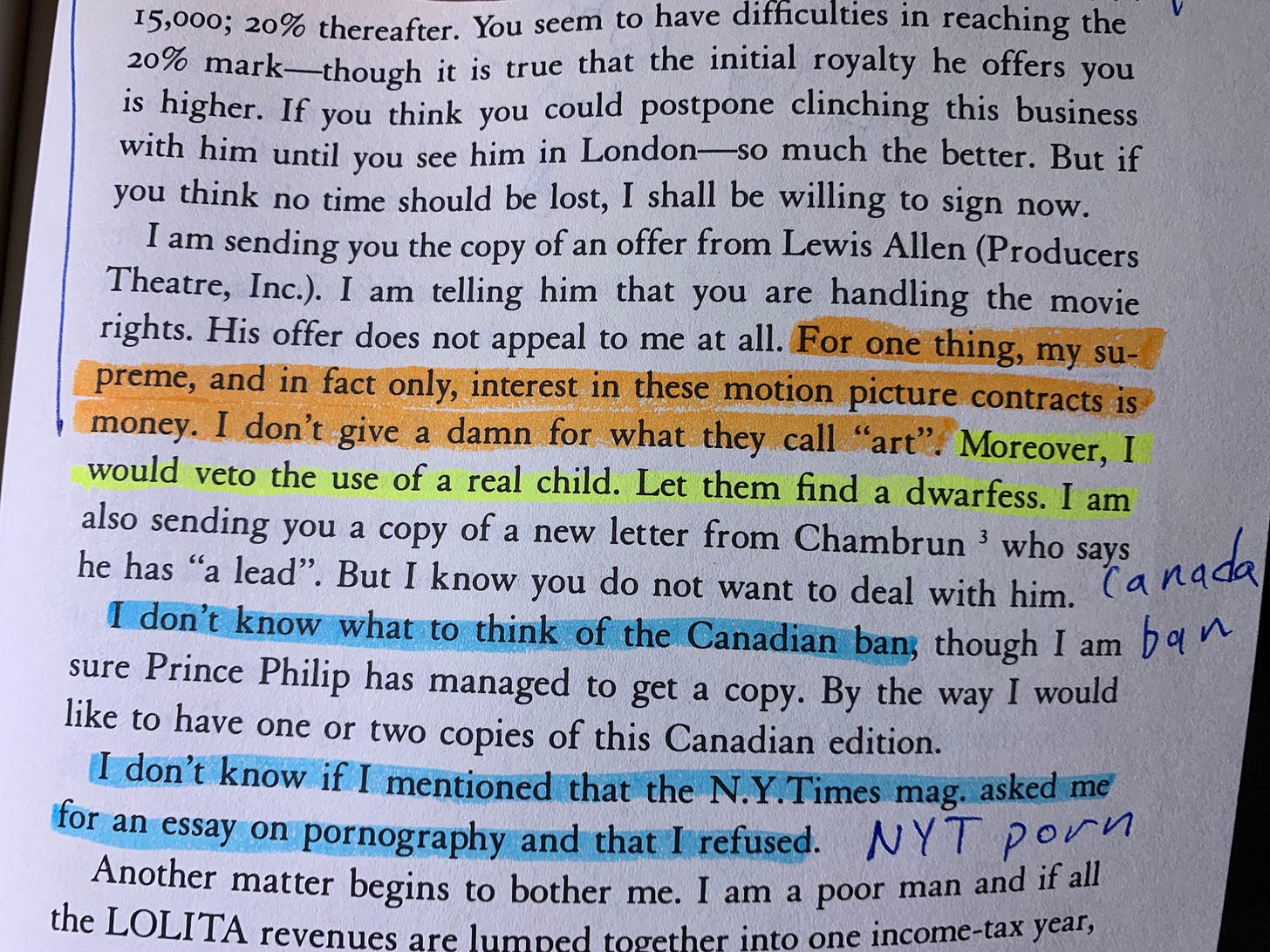

Of course there’s the contemporary “elephant in the room” when it comes to the great Russian-American 20th century author: Lolita. Lolita—1955, first published in France by an avant-garde publisher of literature and porn, later published in 1958 in America by Putnam—for anyone who’s been living under a rock or in a cave for the past half century, is a first-person novel about a man (Humbert Humbert) who, after his wife dies, falls in love with his 13-year-old stepdaughter. He very much knew—based on his letters—that this was a sketchy, risky publishing endeavor. Leading up to publication he repeatedly made editors, agents and publishers promise to keep the manuscript and his name secret. He originally planned to publish using a penname. But eventually he found a French publisher and agreed to release the book using his own name.

By 1958 Nabokov was fairly well known in the literary world but not as much in terms of general readers. Lolita being banned by the French government for a while, and not being available in the States for three years post French publication, only fanned the curiosity flames. This was a time of serious American censorship—think Henry Miller and Allen Ginsberg. When reviews, both negative and positive—the New York Times called Lolita “perverted”—started streaming into newspapers and popular magazines pre-American publication, the flames only rose higher. Curiosity was peaked. Most serious writers supported the book as genuine literature, as did writers in the 1930s when discussing Henry Miller’s Tropic books. By the time Lolita was finally published in the States in August, 1958, it exploded. Lolita made the almost-60-year-old Nabokov famous.

Over the past couple decades the notion of artists being artists has more or less vanished. There is, in many young quixotic contemporary minds, no difference between an “I” narrator and the author him/herself. Once, it used to be taken for granted that this was rarely the case. It could be the case, partially or close to fully, but it was certainly never assumed or expected. Writers were artists, and artists play with style, language, dialogue, plot, imagination, etc to create something new, fresh and original. Sure, some or even much of it might be based on “real life,” but that didn’t mean the novel was actually memoir in disguise.

Now, that’s all changed. The author, in many minds, fundamentally IS the first-person narrator. Even a third-person narrator is now brought in for investigative prodding. God forbid you create a character that goes “out of his cultural, racial, gender lane.” Then you’ll really have a lot to answer for. This thinking encourages the idea that you should solely (especially if you’re white, and especially especially if you’re the dreaded WSM: White Straight Male) write strictly “what you know” and only about your own myopic view of the world, aka about your stunning, absolute, authoritarian privilege (which no other group has: Remember, all white people are the same, especially all white men).

This is a long way of saying: Some believe that the narrator in Nabokov’s novel, who the author referred to as a “moral man doing an immoral act,” is actually a stand-in for Nabokov himself. Either he actually did the same thing his narrator did in real life, or else, at a minimum, he wanted to, and would have had he possessed the option. Surely the author at the very least must condone the child-molesting narrator.

First off: This is ludicrous. It’s akin to saying, anytime you have a certain type of, say taboo, thought, that then means you’re obviously a bad person. No. It means you’re a human being. We all have weird, out-of-the-blue violent, harmful, taboo thoughts. It’s normal. What’s not normal is acting out these thoughts (or sometimes compulsions, urges, desires, etc) in real life. These are two extremely different things. Thinking about taboo things: No problem. Acting them out: Major problem.

Nabokov created a character who clearly acted immorally and did the wrong thing. No rational reader can plow through Lolita and not be on some deeper core level disgusted by Humbert Humbert, an older man essentially raping a 13-year-old girl. (The novel is actually based on the true-crime story of Sally Horner, an 11-year-old girl kidnapped by a convicted rapist in 1948.) And yet, in my and millions of other readers’ point of view, neither can you honestly read the novel and not also on some level feel sympathy and even empathy for the sick, morally reprehensible central character.

This is the genius of the book: Nabokov’s innate ability to make us “care” about a very sick man. This reminds me of the 2019 film Joker, which I just recently rewatched with my wife. Joker is clearly sick and diabolical and sociopathic and out of control. And yet you can’t watch what he goes through—at work, on the streets, at home, from the perspective of his serious mental illness—and not also conjure up pathos.

I submit the idea to the culture now that we need to return to the Artist’s Role of creation being God. In other words: Let imagination reign supreme. We should be allowed to create any kind of character doing any kind of action, good, bad, ugly, or all and more. Art is a reflection of real life, a mirror of sorts, while not being solely this but also more. Art also serves as a sounding-board for our thoughts, our joys, our nightmares, our deepest fears, our taboo terrors, etc. The best writers force us to look at ourselves, especially when we don’t want to. Writing isn’t about safety, and it certainly isn’t about confirming our [liberal] biases. It definitely isn’t about writing only “what you know” and “staying in your cultural/racial/gender lane.”

Art, as Nabokov perfectly-imperfectly shows us, is about vulnerability, risk, guts, power, danger, love, joy, hatred, and the whole spectrum of human emotions. It’s about facing fear; facing death, even. It’s about radiant transcendence in the form of language. It’s about syntax and grammar and lyricism and style.

It’s about throwing a punch into the wild darkness of mankind, leaping up to our collective potential, facing down our deepest innermost demons, cutting our own spiritual skin and watching ourselves bleed, taking risks for the sake of imagination and possibility.

Art is, as Nabokov said, Truth.