Like my writing? Here are some ways to support me:

1. Re-stack this post

2. Share with friends and family

3. Subscribe for free, or paid $5/month; $35/year; $200 Founder

4. Buy my literary YA novel HERE ($3.99 eBook) and review it on Amazon (the book is available everywhere now: Ingram Spark, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Bookshop.org, etc etc)

5. Like/comment

*

But people have forgotten what literature is. Literature isn’t there for you to feel ideologically satisfied. It’s not intended for you to “like” the protagonist. It’s not made to make you feel happy, safe or protected. You’re not immunized with literature against annoying, spoiled, bratty central characters. That’s not the point. The point is to nail down some kind of universal human experience, something that makes you think, that challenges your assumptions, that annoys you yet pushes you, that makes you question your underlying ideas. If you had to “like” literature we’d be in a lot of trouble and a lot of books wouldn’t be read. (Which sadly I suppose is the case now.)

~

Fewer people read today than ever before in modern times. Books used to be common, the TV of a whole generation, up until the 1950s. Since then tech has basically destroyed all that. Social media was the final murderer, replacing books and TV with 2-second clips getting 12 million views. We’ve raised a whole generation of socially-awkward, anxious kids who have little to no understanding of American history, read little to nothing in terms of books, are highly ideological, and are more interested in internet culture wars than serious debate, disagreement or dialectics. (Not to mention worthy literature.)

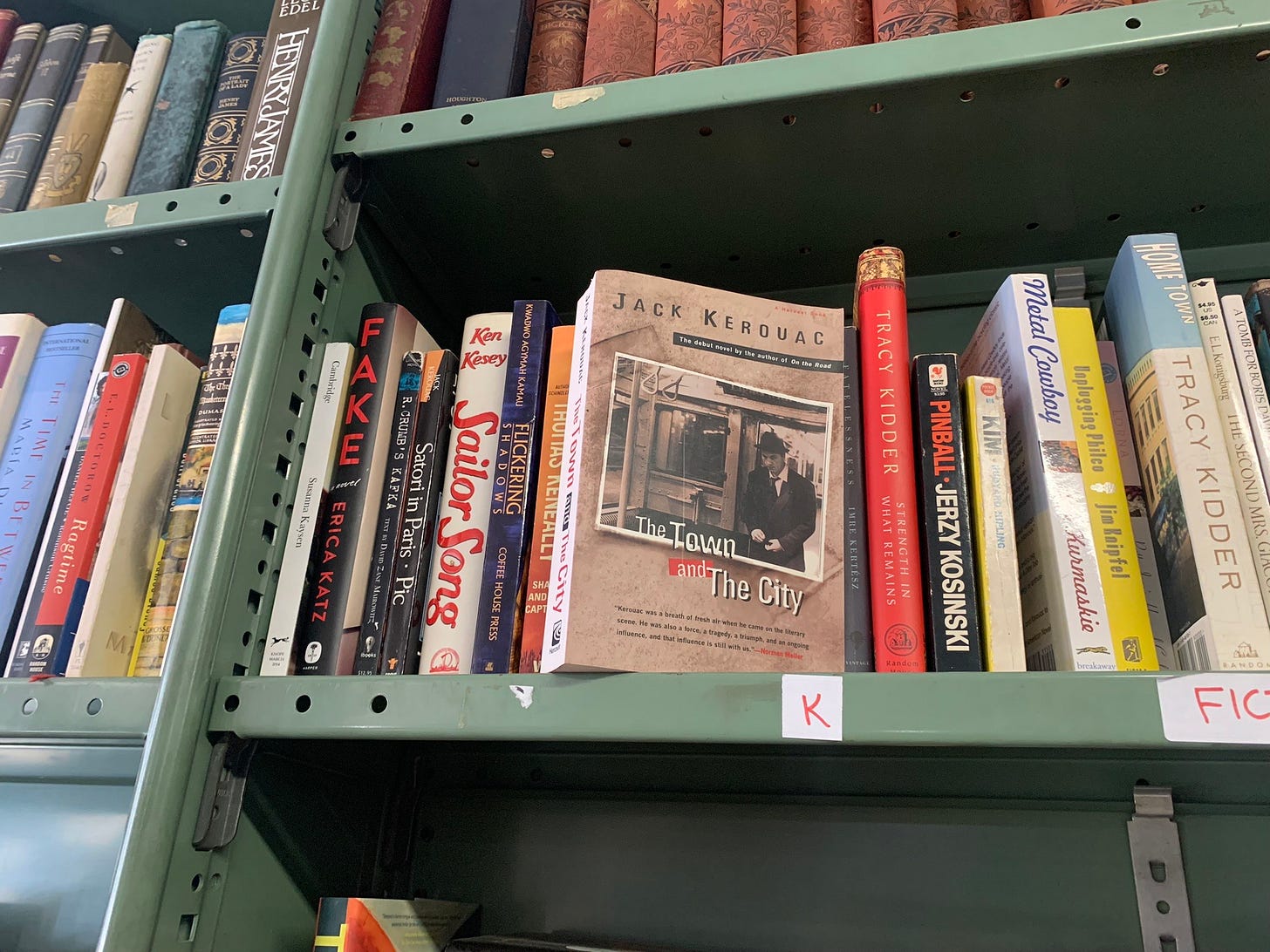

Into this stew of confused entropic anarchy we have the literary culture wars. Everybody knows about this. Hemingway was actually a terrible writer, not to mention a terrible human being, a womanizer of the worst magnitude. Catcher in the Rye is a trash novel written about a spoiled white kid who deserves to get punched in the face. Nabokov, a la Lolita, was a sexual predator and molester whose book should have been panned and censored back then but certainly should be now. Kerouac was a sexist piece of shit who couldn’t write, a weak, angry man who hated women and used them for his benefit. Henry Miller clearly hated women and used them only for sex and as social objects for his prose. (Just like, of course, to be contemporary and use a non-literary example: Jerry Seinfeld was never funny and once dated a teen girl in his 30s. Therefore: Terrible subhuman misogynist.)

Etc. On and on, ad infinitum.

The new literary royalty pronounce that writing should be anti-male, anti-White, and blatantly ideological. They claim that all of publishing is still almost completely White, and that Black and women writers just don’t get a fair shake. If you point out the fact that the internet has gone absolutely bananas since 2020 with supporting Black writers, or if you point out that every major bookstore punches you right between the eyes the second you walk in the doors with Black and non-White authors, if you consider the fact that more and more non-Black authors have complained about being rejected and censored by publishing, and despite the fact that most literary agents are women, and despite the fact that most readers are women, you of course get an angry and immediate eyeroll.

It's the classic Art Versus Artist argument which we’ve been having nationally and globally for generations. Can you read someone like, say, Henry Miller or Charles Bukowski and appreciate the art while also having an opinion about the subject matter, but separate these two things? If you can’t then you lack basic critical thinking skills. Think this is “both-sides-ing it?” I have news for you: Looking at both sides is also a factor of critical thinking. Always, always look at multiple sides of any issue; if you don’t, you aren’t truly understanding the issue, whatever it may be.

*

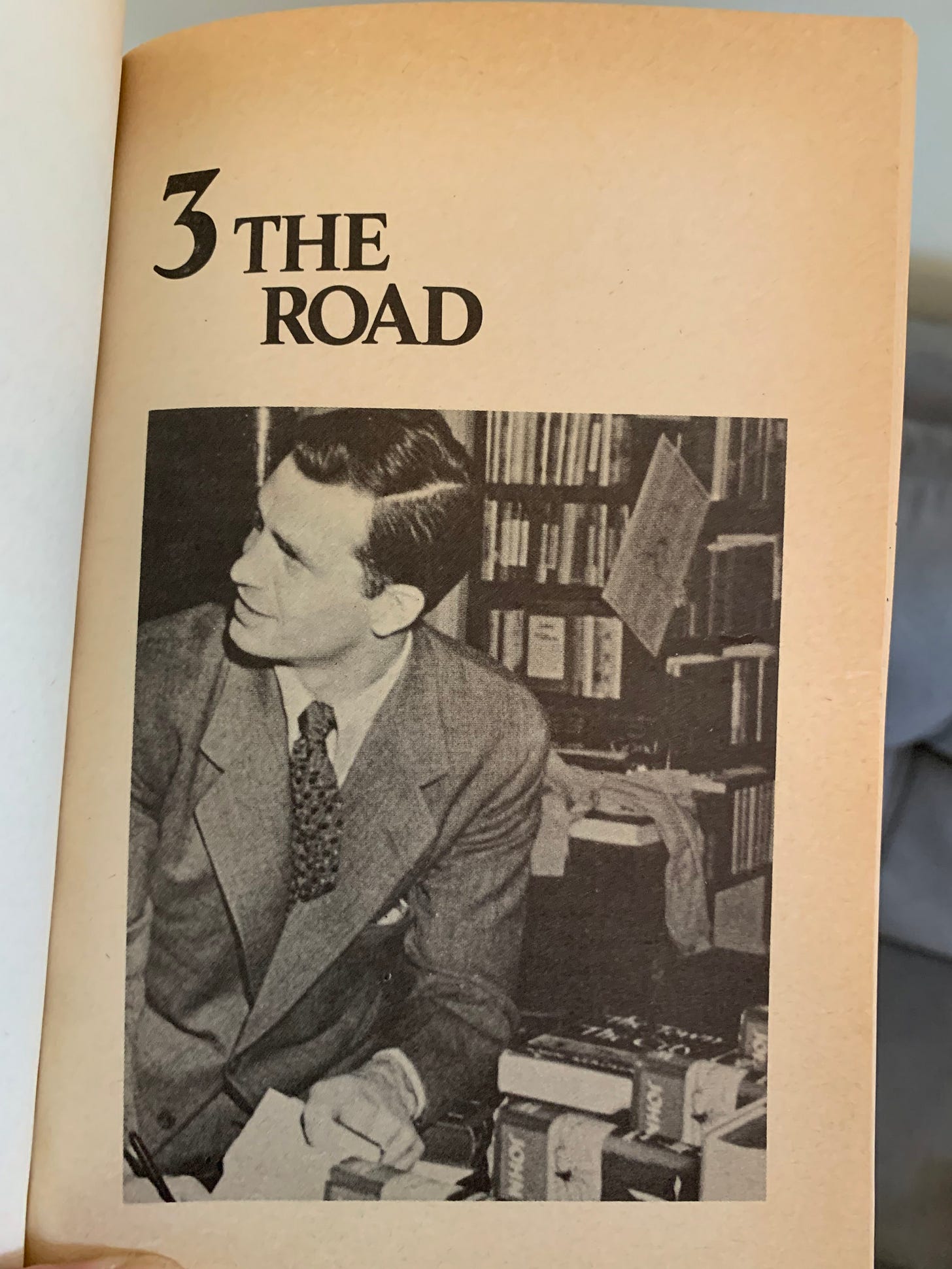

Kerouac. He changed my life. (Some of you are now saying, Blah blah blah, Another White Man Who Liked Kerouac; boring; NEXT! Fine. Stop reading.)

I first read On the Road (1957) when I was 22 years old, circa 2005, when I was living with a punk buddy in a tiny one-bedroom apartment on Thomas Avenue in Pacific Beach, San Diego, about a 15 minute walk from the beach. We were like two circus clowns in that place; we stood out like a line of cocaine twisting between two classic novels. Surrounded by surf-bros and beach-bunnies and military people, we hated our new hometown. We’d moved from our native Ventura, a few hours north along U.S. Highway 101, desperate to get out and “see the world.”

The novel challenged my existence, challenged by bourgeois upbringing, challenged my notions of what it meant to be alive in the world. Kerouac’s book spoke to me, as if a hand reached out from the book’s pages, an arm from the musty, ancient 1950s and grabbed my collar, shaking me and exclaiming, LIVE, goddamn it!

I was a rich kid who’d gone to Catholic college-prep high school. Though I’d been drinking hard since sophomore year, and I’d hopped the freight train of anarchic punk rock, I was still in many ways innocent and naïve. It was around this time that I went back to my childhood roots—my mom was an author and she had an incredible library of classics—and started writing in a journal. At first it was bad, immature poetry, and then my earliest attempts at short stories; fiction. I’d always been a reader—my punk friends in high school encouraged me to read Brave New World, 1984, Catcher in the Rye, etc—but I’d never read anything that honestly, truly “changed my life.”

On the Road was radically different.

I remember reading the novel. It was summer. I worked a dead-end retail job in nearby La Jolla. My roommate was gone all the time, at punk shows, working at a Halloween party store open year-round, and sleeping over at his punk girlfriend’s house on SDSU campus.

There was something new, fresh, unique and totally different about this novel. For years I’d read about the Beats but, other than Ginsberg’s poetry, I hadn’t ever actually read any of their work. On the Road was the first novel I ever read that changed the way I thought, both about what and how a writer could put prose down on the page, and about my actual real life. The novel challenged my existence, challenged by bourgeois upbringing, challenged my notions of what it meant to be alive in the world. Kerouac’s book spoke to me, as if a hand reached out from the book’s pages, an arm from the musty, ancient 1950s and grabbed my collar, shaking me and exclaiming, LIVE, goddamn it!

Finishing the novel I knew something had changed inside me. Something fundamental had been rearranged, cosmically adjusted, altered in some profound, new way. I started working as many hours as I could. I didn’t go out much. I drank alone at the quiet, dark apartment. I had decided to follow Kerouac’s literary ghost and go “on the road.” I felt excited as well as terrified. Though I’d loosened the tie of my middle-class life when in high school—with the heavy aid of alcohol, punk rock and danger—I hadn’t really ever “taken off” on my own. I’d always cherished solitude and even loneliness, as my parents both had. I had friends and I dated girls but I liked being alone. But sitting around in San Diego wasn’t doing it for me.

So, when our one-year lease was up in June, 2006—I was now 23—my roommate and I split off, diverging in different directions. He went to Arizona to go live with an old mutual friend in Phoenix. I boarded an Amtrak train in downtown San Diego bound for Portland, Oregon, where one of my best high school punk buddies was going to college and living. That would be the start of my first wild Kerouacian adventure.

*

That summer I took the train up north to Portland, twisting through some of the most gorgeous parts of northern California in Shasta County. I recall sitting, gazing out the thick double-pained windows, seeing the thick Douglas Fir all around me, snow in the distance even in June, and feeling free. I had a discman and I played a lot of Tom Petty during this trip, particularly the song, Straight into Darkness. This song seemed to somehow embody something secret, crucial and metaphysical during the trip. It drove an electric, dramatic shiver down my spine when I listened to it. I was living half in reality, half in fantasy.

I stayed in Portland with my buddy and his five punky-vegan-hipster roommates for a week and then started hitchhiking for the first time. The plan was to head south from Portland back down to California, and then catch another Amtrak train in San Diego again, east across America to New York City for the first time. I didn’t want to fly by plane; that completely missed the point. Too many people were worried about how many countries they’d been to when they should have considered how they traveled, not where or how many places. Americans seemed to have things ass-backward.

Kerouac was the driver behind all this travel—including of course the method—but I also possessed, like the young protagonist stand-in for Kerouac in On the Road, Sal Paradise, a deep thirst for adventure, life experience. The novel had taught me that education wasn’t the crucial component of being a good writer: Life experience was. Good writing wasn’t about doing the MFA or going to writers’ conferences, it was more than anything else a lifestyle, a sensitivity, a sort of metaphysical vision, a way of seeing the world. It was, I felt, innate, not learned. You either had that inherent talent and vision or you didn’t. Kerouac, I knew, had it in spades.

One of the first experiences I had was meeting a guy on the side of the highway about an hour south of Portland on I-5 who convinced me to go to what turned out to be an AA meeting—this is ironic—and then got me to steal a car with him. We didn’t get far before being pulled over by police.

From there my adventure continued. I caught a ride with an eighteen-wheeler and the driver told me stories about his older brother who went to prison for stabbing a Marine in a bar back in the 60s. We listened to Johnny Cash on low volume the whole ride. I slept in random spots off the highway behind trees and brush. I waded through creeks and rivers. I caught dozens of rides with random strangers. I made friends with some drifters, heading to Humboldt for the trim season. I stayed with another old punk friend in Arcata. And I made my way back to S.D. where I caught that train east for over 72 hours and arrived in New York City, where a whole host of new adventures began.

All told I was gone for three months. I returned to San Diego in the early fall a changed man. I had learned what America was. I’d learned how to take care of myself in hard circumstances. I felt deeply independent, self-sufficient and confident. I’d lived a life not dissimilar from On the Road, yes, but also Into the Wild, Down and Out in Paris and London, and Tropic of Cancer. I got a small one-bedroom apartment in a different part of town on my own and got my old retail job back.

I would do many of these big two, three, even four-month thumbing trips around the nation over the years. In 2009—when I was 26—I drove across the country from SF to NYC and then after a few weeks hitchhiked all the way back. I must have driven cross-country half a dozen times, and taken trains all the way across four or five. As you can imagine, I had incredible, wild, dangerous adventures. I learned a lot about myself. Weeks went by without taking a shower. I stunk and I liked my stink. I felt as if I’d returned in some powerful way “to the land.” Sometimes I thumbed through my battered paperback copy of On the Road. I loved the magical prose, the rhythm and cadence, the way Kerouac described the mountains, rivers, deserts and fields. America felt magical, golden, complex, like some glorious illusion. And most people didn’t even know America, especially Americans.

*

In 2010, age 27, I hit a spiritual bottom and got sober. I quickly realized how immature, selfish and confused I still was. I was on and off estranged from my family. My jobs were always low-paid and dead-end. I didn’t have any notion of The Future. I’d been so affected by On the Road that I’d leapt off the metaphorical cliff and it was only now that I was finally crashing to the surface of the Earth. I had no direction, no career prospects, no calling.

Except writing.

In 2008 I’d started writing my own On the Road, which became my first published novel, a roman-a-clef autobiographical novel called The Crew about that moment when everything changed in high school and the internal bomb exploded.

I finished that novel in 2010 and spent over a decade revising, editing and rewriting it until I got it perfect.

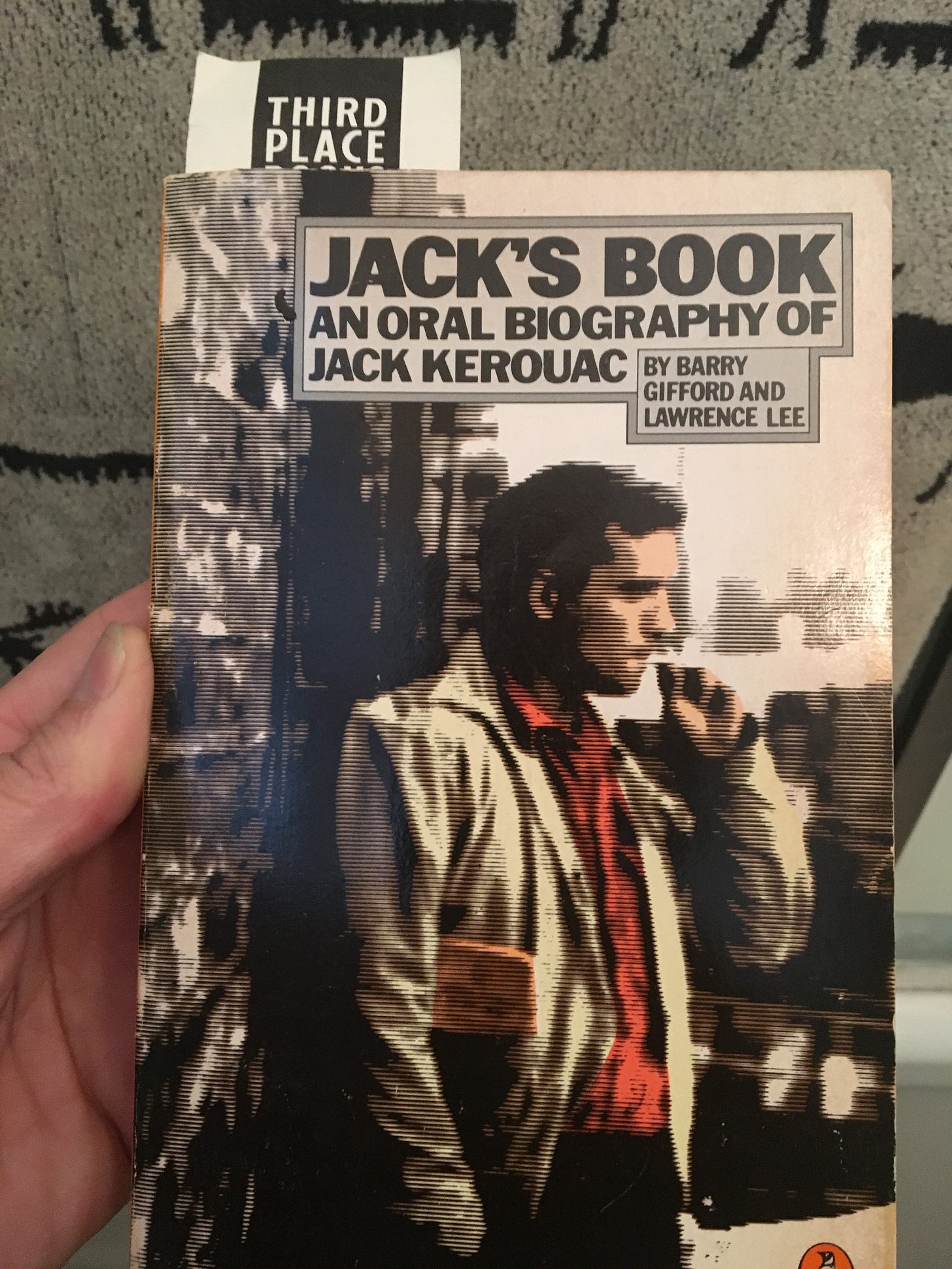

Over the years, as I grew up, became a writer and book editor, fell in love, stayed in one place long enough to finally gain roots, I read several biographies on Jack Kerouac, including my favorite one by Ann Charters. I learned about his terrible alcoholism, his short life (he died at age 47, broke, living with his mother, his liver having exploded while in the bathtub). He was born in 1922 in Lowell, Massachusetts and died in Florida in 1969. Neither he nor his best friend Neal Cassady—Dean Moriarty in On the Road—made it to the 1970s, and somehow that seems fitting. They wouldn’t have understood that generation.

It's largely true—in my opinion—that Kerouac wasn’t a very good writer. Critics—minus that first one for Road in The New York Times when it first came out—loathed Kerouac all his life and literary career, and panned his work universally. Truman Capote famously said of Kerouac’s work, “That’s not writing; that’s just typing.” The longer I stayed sober, the more voraciously I read and, as I did, I began to see that Kerouac, in terms of syntax, style and ability, was not the best writer. Reading classic novels by authors such as D.H. Lawrence, Orwell, Huxley, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Sontag, Baldwin, DeLillo, Franzen, Zadie Smith, Ottessa Moshfegh, Elif Batuman, etc, made me grasp the true and full power of good writing.

Kerouac had missed the mark.

And yet, On the Road, as well as Dharma Bums, The Subterraneans, Big Sur and a few others, were brilliant in their own way. While not masterpieces of literature, they—especially Road—caught a historical moment. The 1950s we’ve been told were the boring decade, the time of the “man in the gray flannel suit,” the time of mass conformity. And yet under the surface was a wild surge of savage sensitivity, contemplative angst and ripe rebellion. No novel of that era exemplifies this better than Road.

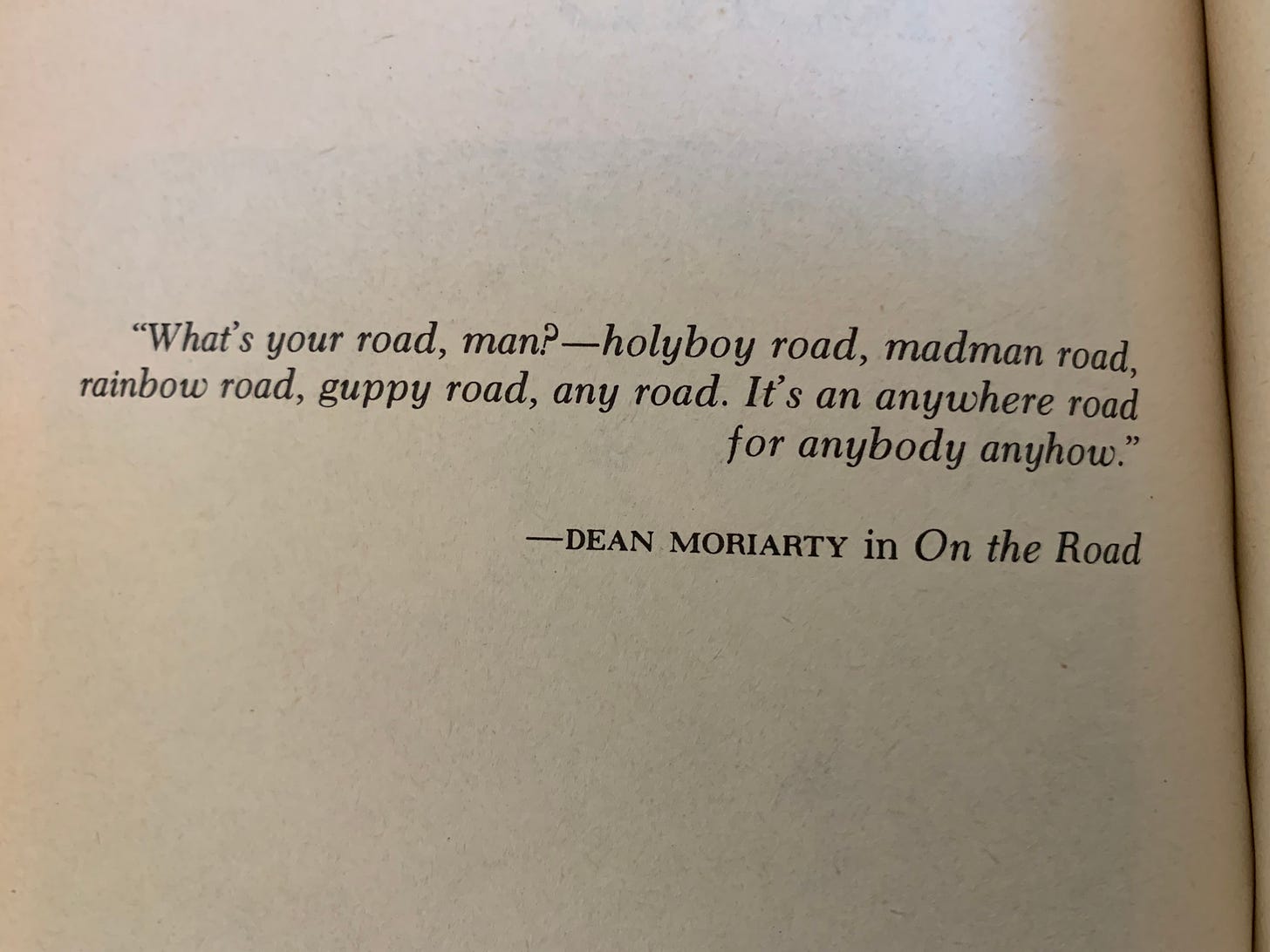

Some people—especially many in Gen Z—like to write the novel off as just some jack-off white men stealing stuff, drinking too much, mistreating women and driving aimlessly around the country for seemingly no reason. But the novel is so, so much deeper than that. One might call it the Beat Iliad. It’s the classic inner descent into Hell and return. Sal Paradise sets off to plumb the depths of his own youthful, eager, haggard soul. And he finds what he’s looking for: Vibrating, thriving, electrical LIFE!

There’s a massive difference between existing and living. One is passive, the other is active. Kerouac was searching—in both his real life and his fiction—for the latter, for action. Spiritual action, metaphysical action, physical action, emotional action. The action of the road—externally and internally—twisting and turning and going through mountains and deserts and long open stretches of green fields and yellow corn. Road explores both the outer and inner roads of Man’s Condition.

What Kerouac writes about is America, in all its magical glory. The things that most Americans disregarded and didn’t even think about—hopping freight trains, hitchhiking, dropping out of conventional society—were precisely the things Kerouac was attracted to and leaned into in the 1940s. The 1960s hippie explosion was of course largely formed as a result of the so-called Beat movement. Kerouac never liked nor accepted the media’s designation and coronation of him as “the King of the Beats.” The sad truth about Kerouac is that, sensitive, deep, emotionally fragile man that he was, he committed the cardinal sin of young American writers: He took himself seriously. As a man, but also as an author with something important to say. He wanted his books to be taken seriously and discussed sincerely. They never were.

I think the media fundamentally misunderstood Kerouac. He was a man classically ahead of his time. In some ways I think he’s still ahead of our time. He intrinsically grasped something most don’t: The journey is both inner and outer. It’s not how many countries you’ve been to; it’s what you discovered inside while traversing the globe. In order for someone to understand the world, they first need to understand their own country. And by knowing intimately your own country one might then grasp the nature of one’s soul.

Being a sensitive, needy artist and not being taken seriously led Kerouac to join the sad mass fray of alcoholic authors. (Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Cheever, London, Wallace, Joyce, Bukowski, [Stephen] King, Capote, Poe, [Dorothy] Parker, etc.) It’s not surprising how common it is for serious writers to become alcoholics. I was one myself. (Still am, only sober.)

We’re sensitive folks, people who have deep, wild vision and who feel things on levels most people can’t fathom. And so we numb out when we feel rejected by the world. Kerouac did that and became a sad, bumbling, self-hating drunk. He could never fully shed his alcoholism, his Catholicism, his shame and guilt around being who he was. I think he constantly battled himself internally, torn between the loving, kind French-Canadian and the hitchhiking tramp who tried to find that existential, mysterious, misty “it” which Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty are always searching for in Road.

Kerouac was not always kind to women in his life, especially in his teens and twenties, the ravaged, anarchic years when he was living what became On the Road. Neal Cassady was much worse, accused later by women of full on forced rape. He was a lady-killer of absurd dimensions, so the myth says. Kerouac also lived in a time of general accepted sexism and misogyny, casual accepted prejudice and racism, and expected white male domination. He was, of course, very much a product of his time. Gen Z loves to use “presentism” nowadays, the notion that people living in previous eras should somehow have been aware of what we now know in 2024. They like to tell themselves that if they were alive back then, they wouldn’t have been like the rest. If they’d been around in the 1850s, for example, they wouldn’t have owned slaves; they’d have been abolitionists.

This is a silly straw-man argument. Look at our culture right now in 2024. Many young people on the left are supporting Hamas, an anti-human terror cult who wants nothing more than to destroy the state of Israel. The truth is that each generation has its own Overton Window, it’s own container of what’s considered normal, conventional, acceptable. Currently it is just fine for rich white elites to claim that all Black people think, act, talk and live the same way. (Racist.) That all white people are white supremacist and evil. (Bullshit.) That all men are shit. (Absurd.) That Israel doesn’t have the right to exist. (Deeply antisemitic.) Etc. Gen Z’s kids and grandkids will look back in 20, 30 years and be shocked at what was considered acceptable in our time now.

Kerouac wasn’t perfect—no one is—and I don’t by any means defend everything he wrote, said or did. As I argued earlier: I don’t think in the end he was that good of a writer. (Probably he was not that “good” of a man, though a very human and messy one, like us all.) I think he nailed a certain time in America. Like Trump—ironically—he had his pulse on something important when everyone else was looking away, distracted by their own gaudy, glittering bullshit. Kerouac drilled down into the American psyche and found something unsettling, new and glorious. A gem encapsulated by tons of cultural trash.

I don’t defend some of the things Kerouac said or did, especially with regards to women. Just like I don’t condone the behavior of Humbert Humbert, the child rapist in Lolita, by Nobokov. Just like I don’t deny the irritation I sometimes feel when rereading Catcher in the Rye.

But people have forgotten what literature is. Literature isn’t there for you to feel ideologically satisfied. It’s not intended for you to “like” the protagonist. It’s not made to make you feel happy, safe or protected. You’re not immunized with literature against annoying, spoiled, bratty central characters. That’s not the point. The point is to nail down some kind of universal human experience, something that makes you think, that challenges your assumptions, that annoys you yet pushes you, that makes you question your underlying ideas. If you had to “like” literature we’d be in a lot of trouble and a lot of books wouldn’t be read. (Which sadly I suppose is the case now.)

You don’t read David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest because it’s fun, easy, not irritating, likeable, etc. It’s a fucking slog. Part of it feels like going through Army boot-camp. It’s incredibly long. Parts of it are stupidly dense. Some of it must be reread six times. There are hundreds of pages of footnotes.

This book (Infinite Jest) was published in 1996, a time when TV was taking over people’s brains, devouring the nourishing act of reading literature. It’s only grown worse since then. No wonder there is so much lying, moral panic, confusion and ahistorical madness going on in our contemporary times. Not enough people still read, and the ones that do are mostly not challenging themselves with sincere literature. Instead, they’re reading short, biased news articles which do not challenge their ingrained assumptions and views, or novels which do the same and are more ideology than Art.

For me the source of the problem always comes back down to The Internet, broadly speaking, social media and iPhones more specifically. Our attention has been walled off, bubble-ized and fragmented. Books are too long, take too much time and concentration. History is messy and complex and therefore hurled into the trash heap, replaced by easy binary Manichean narratives which help nobody and keep society eternally divided.

Please learn to separate the art from the artist.

Please learn to understand people within the context of their time.

Please learn to judge people by the content of their character, not the color of their skin, or by the sex they were born into.

Kerouac is a symbol, a reminder of a time and place in American history. His jazz-spirit lives on in the same way the Ramones still inspire teens to get into punk: Because there’s something universally human underneath all the pomp and bombast, underneath the sexism and male chauvinism, underneath the drinking and wild carousing, underneath the fragile male egos of Kerouac, Cassady, etc.

Kerouac’s legacy lives on because there will always be a time to get out and “hit the road,” symbolically and literally. To deep-dive into the misty, mysterious unknown and find yourself in the deepest way, to throw caution to the wind and stick a thumb.

When I was about 20, I submitted a paper arguing that Humbert Humbert was the protagonist in Lolita. I could still defend this argument - and would - not because I am a fan of Humbert nor that I was a victim of abuse, but because Nabokov WROTE him as the protagonist. Whether Nabokov himself was a predator, or that he was sexually abused (I believe I read that he was - which would lend to the creation of a protagonist abuser if he never got help), there is plenty of evidence in the novel that paints Humbert as the protagonist. I wish I still had that paper - I got an A.

The beginning of your post reads a bit like the angry generalizing women you speak of. There is certainly a subsect of women who publically rant about weak men and fucked up male writers from days of yore, but you leaned a little bit into some generalizations yourself. We aren't all like that. Also, I know several men who, after reading On The Road, took to it themselves. I think it's a good thing to do. One guy, a high school super jock I graduated with, ended up writing several books afterward. Not sure what he's doing now, but he does make mention of me in Chapter 1 of his first book.

Great stuff! I had a sideways entree into discovering Kerouac. I saw a late night showing of The Subterraneans (George Peppard, Leslie Caron) on TV, which led me to the book. He was my literary hero throughout my adolescence. I first read Dharma Bums as a teenager, having recently begun using drugs and alcohol and loved all the accounts of the partying and revelry. The second time I read the book was in my 30’s, newly sober and loved all the accounts of the spiritual seeking. I agree, he’s not a great writer per se, definitely an acquired taste. What’s always stood out and resonated for me is his passion and aliveness of his lived experiences that jump off the page