***Please consider going paid if you haven’t already; you’ll gain access to ALL my writing from the past 12 months. Only $40/year.

###

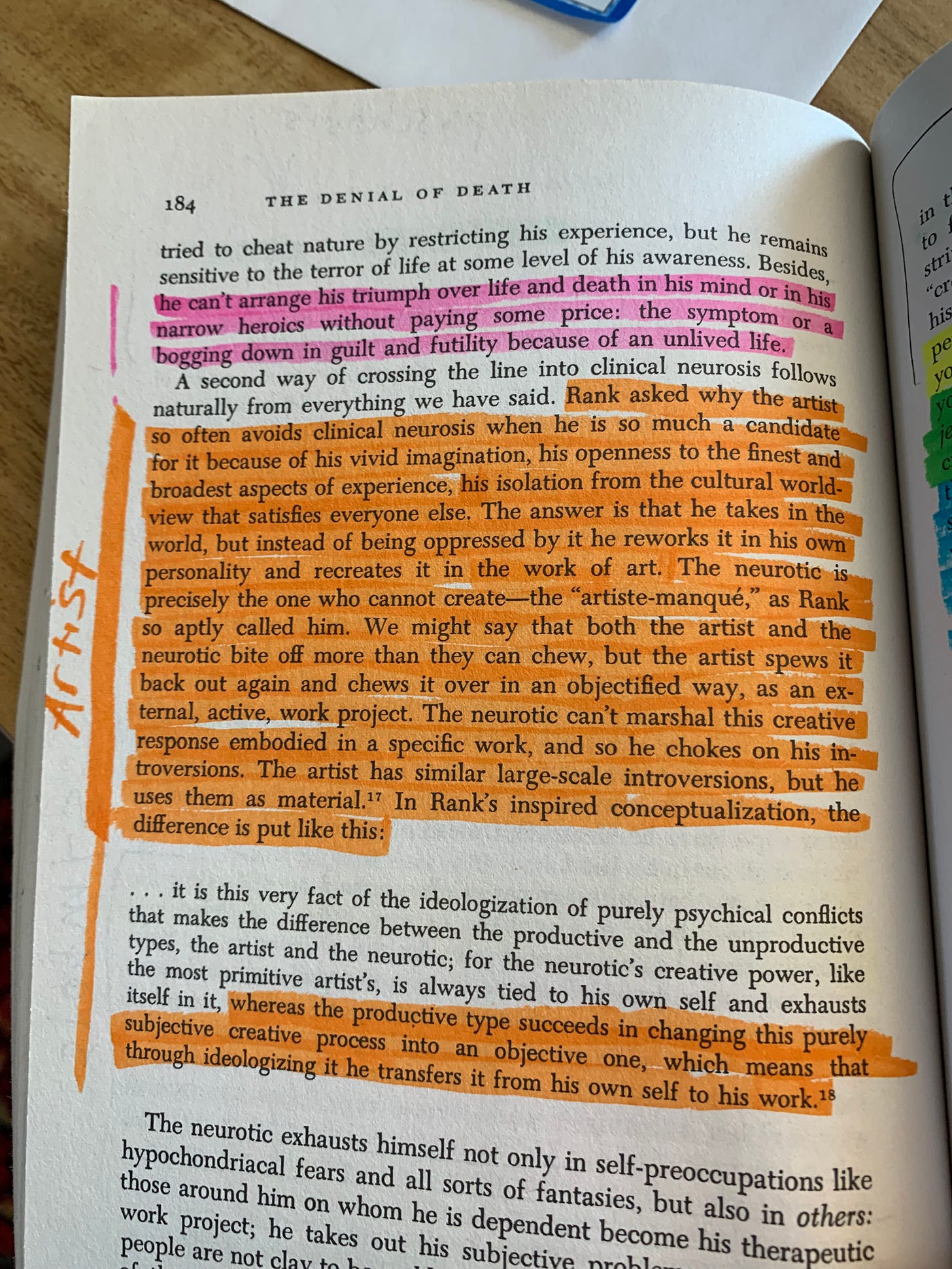

“Rank asked why the artist so often avoids clinical neurosis when he is so much a candidate for it because of his vivid imagination, his openness to the finest and broadest aspects of experience, his isolation from the cultural worldview that satisfies everyone else. The answer is that he takes in the world, but instead of being oppressed by it he reworks it in his own personality and recreates it in the work of art. The neurotic is precisely the one who cannot create—the “artiste-manque,” as Rank so aptly called him. We might say that both the artist and the neurotic bite off more than they can chew, but the artist spews it back out again and chews it over in an objectified way, as an external, active, work project. The neurotic can’t marshal this creative response embodied in a specific work, and so he chokes on his introversions. The artist has similar large-scale introversions, but he uses them as material.”

― Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death

I’ve mentioned this book several times in related posts, Ernest Becker’s 1973 Pulitzer-Prize winning book, The Denial of Death. I finally decided to just write a whole post on it because why not? Clearly, it’s had a profound impact on me. I first heard about the book during a podcast by Sam Harris discussing death.

For a very long time, I’ve had an intuitive feeling—rarely sketched out consciously on the page or verbally—that death underlay all human emotion and behavior in some way. It seemed fairly obvious. Throughout my life, I’ve noticed that most people seem to wear what Becker calls a “character armor,” a sort of metaphysical suit of armor that makes them magically believe that they either won’t die, or it’ll happen to “them” or that to the extent that they will die it’ll be a long, long time from now, and there’s no need to worry or think about it. (Why would you, right? Why go into that morbid, macabre corner of consciousness?)

But, as the above Becker quote suggests, the artist (and the neurotic, which are usually one and the same), “bite off more than they can chew.” Here’s another Becker quote:

“The ‘normal’ man bites off what he can chew and digest of life, and no more. In other words, men aren’t built to be gods, to take in the whole world; they are built like other creatures, to take in the piece of ground in front of their noses. Gods can take in the whole of creation because they alone can make sense of it, know what it is all about and for. But as soon as a man lifts his nose from the ground and starts sniffing at eternal problems like life and death, the meaning of a rose or a star cluster-then he is in trouble. Most men spare themselves this trouble by keeping their minds on the small problems of their lives just as their society maps these problems out for them. These are what Kierkegaard called the ‘immediate’ men and the ‘Philistines.’ They ‘tranquilize themselves with the trivial’- and so they can lead normal lives.”

Ernest Becker, The Denial of Death

The Artist, then, is the opposite of the philistine or the “immediate man”: He bites more than he can chew, he is a scatological clown, a cosmic lunatic, a spiritual punker. He’s a weirdo, a revolutionary a freak: He cannot help but “biting off more than he can chew”; he cannot ignore Reality, the thundering cold hard reality of Death, always present, always lurking there just around the corner of existence. The Artist is an ontological mutant. He cannot avoid the anxiety, the dread of being alive. This is what makes him an isolated loner: he is excommunicated from the land of the free and easy, the immediate men (Kierkegaard’s language) who see only the small and immediate right in front of their noses.

I’ve always been fascinated by people in general, society, “community” (there’s something squeamish and grotesque, to me, about this trendy millennial word, similar to the feeling I get about the equally trendy word “intersection”), and how human beings in modern times lie to themselves. Becker discusses this in detail in the book, the lies we tell ourselves about life and death. We try so hard to project outwards, using “perception-management,” to present ourselves and our families, partners, etc to The World. We think—falsely—that if we control the externals this will somehow map onto the inner landscape. But of course it doesn’t.

The privilege of the average person is the ability to lie to themselves about what Becker refers to as their “basic essential creatureliness.” We’re not gods, Becker warns the reader, we’re worms who have self-consciousness, metacognition, and sadly think we’re gods.

We feel this most sincerely as teens and in our twenties: Death is such a far-off illusory fantasy that it hardly feels real in any way. Unless, of course, you experience it directly and first-hand for some reason. In 2007—when I was 24—a good buddy and I were being driven by a woman we’d met at a bar in Ventura, California, where I grew up. We were all wasted. She crashed the car. Multiple roll accident. The car landed on its side. One second I was in the back, drunk, windows down, listening to The Misfits full volume, my buddy and the woman flirting up front, and the next second the car was on its side, part of the engine was on fire, glass was strewn across the road, the woman was pinned against the street in the driver’s side, and my buddy was lugging me carefully and slowly out of the wreck.

In that moment, young and dumb and drunk as I was, I grasped the realism of death.

Becker, as I said, discusses how death denial—a fundamental and unconscious process—affects more or less everyone. It’s near impossible not to struggle with this phenomenon on some basic level. Think about it. As far as we know, we’re the only creatures on Earth who have this crippling (for some) self-awareness about our own creatureliness. We know that we’re here for a limited amount of time, that life is temporary, ephemeral, brief. Nabokov’s “Brief crack of light between two abysses,” as he writes in his brilliant, stunning memoir, Speak, Memory. How do we reconcile these two realities: We have supreme self-awareness of the limitations of our existence…and we die. Not only do we die: We have little to no control, really, over how or when we die. Some control, but very little. And in the end, one way or another, it captures us.

Freud, characteristically for a book published in the early 1970s, is discussed throughout. Like many post-Freudian thinkers and psychologists today, Becker both appreciates the father of Psychoanalysis’s takes on the foundations of neurosis, and also criticizes the many problems and fallacies inherent in Freud’s ideas. If the man was a genius—and I think it’s obvious he was—he was a deeply flawed one, with at once the strong ability to trailblaze and come up with new profound theories, coupled with a bad case of ego, narcissism, sexism, fallacious ideas, and megalomania.

According to Becker, broadly speaking Freud’s biggest mistake was mixing up sex with death (which symbolically are quite linked together). For Freud everything—all neuroses—came back down to sex: Libido; taboo sexual cravings which had to necessarily be stifled in civil society; anal or penile fixation; penis envy; the child’s Oedipus Complex, the sexual desire for the mother and fugue need to alienate or symbolically “kill” the father; etc.

Becker’s point is that: Really, the true bullseye wasn’t sexual repression but death repression. What we fear is not sexual denial but death denial. The neuroses we experience stem not from taboo sexual cravings but from the deep terror of the fact that we die. Ergo, we are trained, consciously and unconsciously, by parents, society, the media, culture, peers, books, TV and film, etc to narrow our spiritual and metaphysical vision down to manageable size.

Don’t look at Death, everybody seems to be saying; focus on work, on staying busy, on online dating, on Substack, on what clothes you own, the kind of car you drive, how much money you have in the bank, where you’ll travel next, what you say and how you appear on social media, etc. In other words: For the love of God keep yourself distracted. The best thing to do is get married, have kids, get real busy with life. Because that ugly, uncomfortable thing underneath all of it is scary; terrifying, in fact, and, like the sun, it’s best not to look directly at it for too long, ideally not at all. We’re of course encouraged to do all of this non-looking via our economic system: Capitalism, one might argue, is the anti-death serum. Consume consume consume.

But like I said: Most Artists don’t have this privilege. They’re too sensitive, too self-aware. A primal, crucial layer of self-protection (character armor) has been ripped off from their symbolic “self.” They cannot operate in the world of make-believe; they don’t have the ability to lie to themselves, to pretend that things aren’t the way they are. They see that Death is always there, lurking in the shadows, and they constantly wonder if something might be “done” about it.

Sometimes the “thing done” arrives unintentionally in the form of neurotic symptoms. For example, here’s one I have: “Harm O.C.D.” Click here to read my piece on this from a while back. This is a type of O.C.D.—Obsessive Compulsive Disorder—which includes scary thoughts of harm, to self and others. Of course these looping, discursive, intrusive thoughts never become actions, and that is crucial. But they nevertheless can lay me flat on my ass if I don’t take meds. Much of the O.C.D. literature I’ve read—and Becker discusses O.C.D. as one neurosis in The Denial of Death—talks about O.C.D. being a symptom of the desire for total certainty about things in life. It’s a sort of timid perfectionism gone awry. Because the thing is: There really aren’t any “certainties” in life…other than the clinical fact that we die. Everything else is more or less up for grabs. And even when things do go our way, they often don’t go exactly the way we hoped, planned or expected. (Lord knows expectations will get us every time.)

And of course there’s always suicide. I confess that clinical depression runs in my family. Ditto alcoholism. I’ve had a few bad run-ins with serious depression and suicidal ideation has sometimes come with it. Sometime towards the very end of 2021 or the very beginning of 2022 I had one of my nastiest experiences with it.

I’d left New York City in summer of 2021. My father was dying. I was suddenly living in a town I didn’t want to live in, taking care of a man I loved yet didn’t feel I knew. I had no friends in town. Covid was still happening. NYC had been a mix of a nightmare and a decade of writing material. (Check out my memoir about living in East Harlem during Covid HERE. First few chapters are free.) I hadn’t physically touched a woman in well over a year. I was foolishly doing online dating which was only making things worse. I was broke and in debt. Virtually no work was coming in. All I did was drive around town picking up meds, seeing my folks, sleeping, reading thick tomes at coffee shops, and wondering what the hell had happened to my life. I was in my late thirties and I felt 55.

At that time I was reading a lot of Camus. Particularly, The Myth of Sisyphus, his thin book where he attempts to grapple with the meaning of life, suicide, the merits or lack thereof. I remember for the first time in my life actually “making a plan,” wondering where I could get access to a gun. It felt scary and out of control. Luckily, I evaded that fate. Therapy, walking dogs for dough, and the making of a single friend all helped lead me out of the morass of terror. But I remember feeling like I had this sudden power. I could take this one simple, wild, existential leap off the cliff of madness we call life and…the gross, beautiful ease of oblivion.

The AA Big Book talks a lot about alcoholics and suicide. Bill Wilson himself touched on it. Almost every alcoholic I know of and have heard speak has discussed thinking about it at one time or another.

Artists, too, who are often but not always alcoholics and addicts as well, have this hypersensitivity, this too-thin non-separation from Death, from the realism of being human, which is to say the realism of our true human condition: being weak, vulnerable, and always just one tick away from the total blotting out of consciousness.

But there’s also another angle here. In the West we tend to laugh awkwardly at people who think too directly about death. People will grin uncomfortably and say things like, God, that’s DARK, or, Man, that’s macabre. To Artists this seems and sounds bizarre, unwieldy, untrue and naïve. It’s akin to pointing to a lion and saying it looks like a house cat. Just call it as it is. Tell the truth. People use all manner of things to avoid this feeling: Drink, drug, sex, work, porn, busyness, you name it. People in the West seem to deeply fear not being busy; being bored. Why? Because if you stayed bored too long you might begin to think about things which are seriously uncomfortable…such as the fact that you, your parents, your kids, your community; everyone you know in your life, including of course yourself, will one day be food for worms. And you don’t know when that might happen. Could be in 50 years; could be in 5 seconds; could be tomorrow; could be next week.

The Buddhists like to form a healthy relationship to death, something which seems absurd and anathema to Western culture. I remember meditating with a group in San Francisco regularly years ago, circa 2015, 2016. The group was called Dharma Punx. We’d gather in a church and meditate. There must have been 150, 200 people. An outer circle and an inner circle. A thirty, 45 minute silent meditation and then a Dharma talk. One time we had a guest, a Buddhist nun who’d volunteered as a hospice nurse in Southeast Asia for a long time. She wanted to discuss death with us, the cultural clash between West and East. Coming to terms with death. How we’ll lose everything, everyone, eventually. Including ourselves.

It was actually a really beautiful experience. She talked about death gently as we closed our eyes and remained totally silent. And then she did a talk. She talked about how avoidance of the reality of death causes all sorts of spiritual and emotional neuroses and bad behavior. Transference; projection; ego-explosions; codependency; control. Instead of consistently running from the notion of death, she said, why not turn around and actually face death?

Why not view death as one more inevitability of the frail human condition, our most crucial relationship? It was a profound exercise. What, really, was there to be so afraid of anyway? The loss of consciousness? Wouldn’t that simply be like pre-birth? Did you suffer before you were born? Of course not. Because “you” didn’t exist. Post-death you won’t exist either. In a way, this feels strangely comforting to me. It’s like spiritually changing the channel; blam, you’re out.

All the striving, trying, avoiding, denying: Isn’t it all just so much inner work? This brings me back again to Buddhism. To the fundamental idea of accepting things “as they are,” to the notion of being “in the present,” which is really the only moment that ever truly exists; the past is already gone and the future hasn’t happened yet, and when it does happen…it’s the present. It’s really just this moment, and then this moment and then this moment. Until we die. That’s it. That’s life. We paper-over the reality because it’s deeply uncomfortable. We naturally want to believe that life goes on forever, that our kids will carry on to eternity, our parents, our friends and family, our animals. As Freud thought about sexual neuroses, Becker argues that we wear this character-armor for a reason: As self-protection and in order to fit in.

And this circles back to Artists. Becker doesn’t argue—and neither do I—that Artists are “superior” to other people. In fact if anything I think Becker takes the angle that Artists are too sensitive, too fragile, too unprotected, too soft. And yet, it’s also true, and I think Becker understands this, that Artists are incredibly courageous: They have to be; unable to avoid seeing Reality for what it is, they are forced—like Alex in A Clockwork Orange when his eyes are pinned, forced open, making him watch violent films in order to induce in him an aversion to violence as a result—to face Death in the starkest, most brutal terms. Death isn’t some distant mountain peak in the far, distant horizon that is usually obscured by thick fog or clouds and is only sometimes, rarely, partially seen. It is the spiritual ocean Artists swim in every single day. It is all around and inside of them. They cannot look away. Imagine that!

I can’t end without briefly mentioning my father. He died four months ago from terminal cancer after a 23-month-long journey. This journey was very much akin to “peeling the layers of the onion” away, thin gossamer layer upon thin gossamer layer. Slowly, over the course of weeks and months and almost two years, he gave up the things in his life, until finally he gave everything up, and at last his life itself. In many ways he was very lucky, as were we: We had nearly two years with him, and he experienced no pain, and was to the very end sharp as a tack. Cogent. The night before he died we listened to a podcast. And I got to truly know this man who was my father.

But I do remember when Dad transitioned from being sick but somewhat normal (normal for then) to being seriously drugged-up to then dying. The cold blue flesh. The rigidity of his skin. His dead marble eyes. His stiffness. The final cessation of breath. The acknowledging of my father as now being a corpse. Dad was no longer there; he had officially left the building. I remember the out-of-body feeling in the minutes and hours after he died, how it reminded me of my wild twenties, being high on acid or mushrooms. It didn’t seem real; it didn’t line up with “real life.” His body was like a dummy; it appeared and felt fake, drummed up, as if we were all three (me, Dad, Mom) acting in a movie and were doing a new scene. This couldn’t possibly be actually happening, I recall thinking. But it was happening. It was 100% real. More real than anything that’d ever happened in my life prior. Dad had shifted from alive to…not alive. From living to dead. From here to there. It was shocking. Still is.

And that is the thing about death: it IS shocking. Because by definition it is the cessation of the only thing we truly know: Consciousness. How can one grapple with that loss? How can one grapple with the loss of it in a loved one, let alone in oneself? We don’t know, for sure, if anything “happens” internally after death, or spiritually. I personally—and this was my father’s feeling—believe that nothing happens. You’re just gone; exactly as it was pre-birth. Consciousness is simply wiped clean; gone.

That’s the thing, Becker writes, about mankind: The best, closest method we have for touching something like Eternity is having kids, who then have their own kids, and the DNA gets passed down the line; the legacy carries on. But even in this case we’re thinking collectively; historically. Because each human being lives only for a little while, and then, like a bee after the sting, they die. But the child carries on, and, ideally continues the cycle. Man, therefore, is only a sliver of a link in the long chain.

I, however, am not having kids. So there goes that. I am the end of my father’s line. I will one day go to the grave leaving nothing of my genetics behind. This is not because I detest life or the world. It is because I don’t feel compelled to have kids. I feel compelled to write. And travel. And love. I feel compelled to create Art and share it with the world. That’s why I’m here. That’s my purpose. If I can help others along the way, I’ll try. And while I’m at it I figure I’ll do my best to turn around and face death. Because I’m already one of those stripped-down non-immediate men, the deep, hard-thinking ones who can’t avoid the ticking time bomb that is the end of consciousness. I can’t look away. I haven’t even had a drink in 13 years, or a drug in much longer. So I have to just sit there and take it all.

Becker would like that.

“Ergo, we are trained, consciously and unconsciously, by parents, society, the media, culture, peers, books, TV and film, etc to narrow our spiritual and metaphysical vision down to manageable size.”

Pretty much sums up the gigantic hole most of us have in our lives. It’s trained into us. Only the tortured or the painfully self-aware ever wrestle beyond the immediate and pedestrian.

Great piece Michael. Excellent, thought-provoking, and intelligently referenced. Bravo. And fuck you for reminding us how small we are. Worms 🙄

What a thought provoking piece. You nailed so much of what we do to cope (consume, consume, consume; stay busy) and avoid the inevitability that the elephant in the room is indeed going to crush us. Scrambling around him is futile. But how human to believe we are gods who can leash the beast and carry on. Beautiful, Michael.