Listen to my podcast about my own personal book publishing journey

I edited ’s book, Death, Taxes, and Turduckens. See description below. It’s a fantastic book, a fun, fast and easy read. Very compelling. BUY HERE.

Death, Taxes, and Turduckens exposes history’s largest alleged tax heist—the astonishing true story of a reclusive billionaire indicted for dodging over $1 billion in taxes using offshore “Turducken” trusts. This gripping exposé reveals how the ultra-wealthy exploit scandalous loopholes, leaving ordinary taxpayers to pick up the tab.

~

Alex Muka’s general story—being a 90s kid, going through mass literary agent rejections, finally self-publishing, starting a Substack, spending time in Manhattan, NYC, and struggling with alcoholism—is very similar in many key ways to my own story. (Listen to my podcast episode on my personal journey here.)

Muka’s novel, Hell or Hangover—great title, by the way; self-published in 2025—is the result, he says in the end acknowledgments, of a decade of hard literary work, revising, editing, redrafting, getting feedback, working with editors and fellow writers, etc. This, too, I can very much relate to. My debut novel, The Crew—similarly autobiographical, full of hard-drinking, the search for self, belonging and meaning—took me about 16 years to get out into the world. I started my first draft in 2008, when I was 25 and living in San Francisco, still a hopeless drunk, and published it, finally, after probably 500 agents rejected it around the nation, at the start of 2024. So, I started the novel at 25, published it at 41.

But back to Muka.

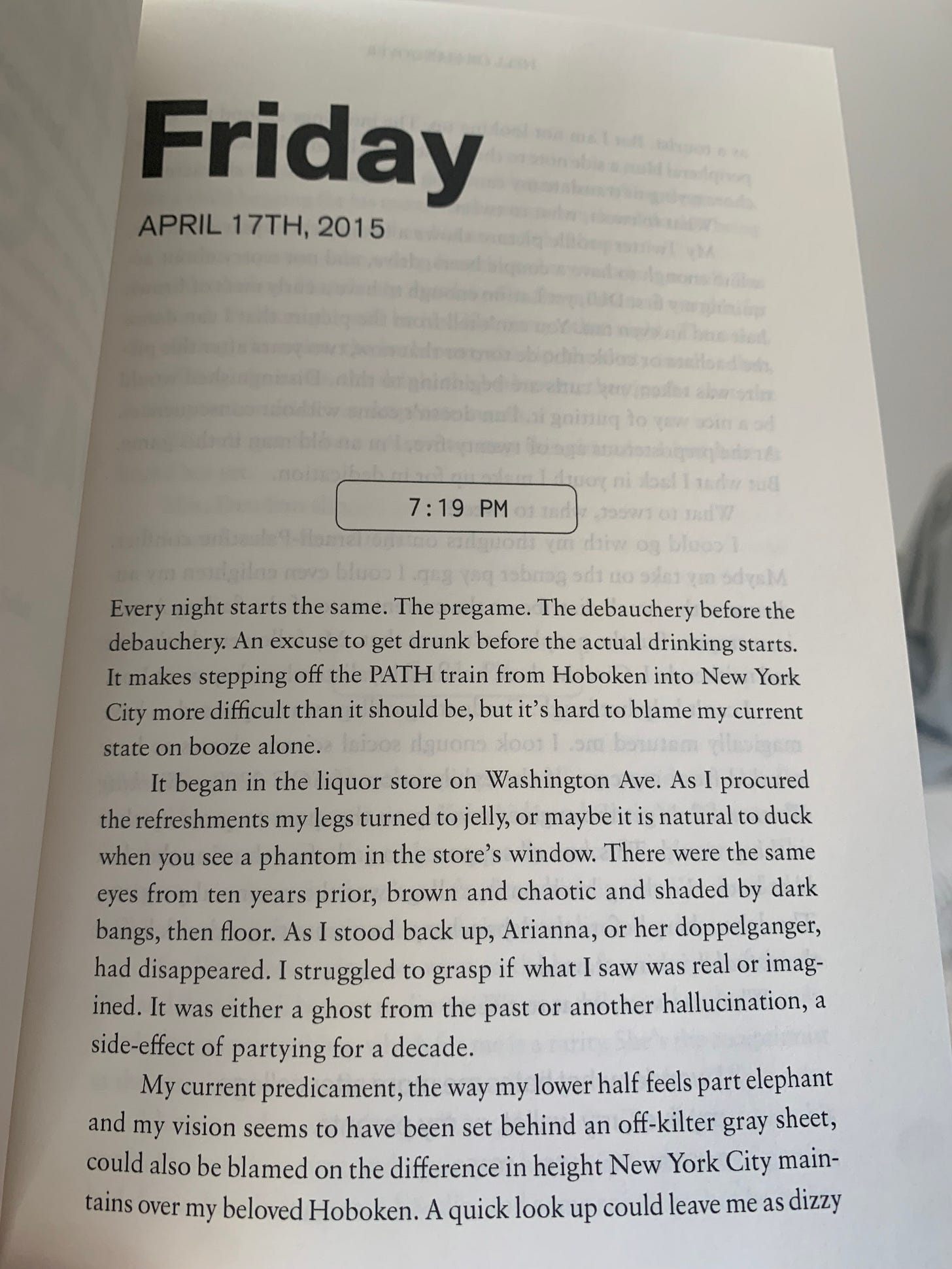

I divided this novel in my mind into rough thirds. First I should say there is a “plot” but the “plot” is secondary to the writing style, the characters, and the humor. I don’t have a problem with plotless or plot-light novels, and Muka does a much better job here than Brandon Taylor, whose novel, The Late Americans, I eviscerated here. In Muka’s novel the “plot” is a horny, drunken 25-year-old half-white half-Cuban who sounds an awful lot like myself at 25. He’s a fucking mess. (I didn’t ask and it wasn’t directly stated but the novel felt and I assumed it was highly autobiographical; at a minimum there is a thick thread of autobiography in it.) Lou, the protagonist—or perhaps anti-hero—gets drunk every day, often trying to swear off the sauce and failing. He endlessly chases girls. He continually falls back on his hot ex who he nevertheless knows he doesn’t want to be with.

The novel takes place in Hoboken, New Jersey and New York City. Lou is lost, working a shit job he hates as an app salesmen (his father, who he has major friction with, owns the company), drinking too much, always looking for sex, and is a classic man-child, as the narrator himself admits. His biggest fear is committing to any kind of real relationship. He refuses to meet the parents of women he’s having sex with, and he regards social media photos of he and a woman to be complete blasphemy. Any pressure at all from a woman—in any form—he considers A Cardinal Sin.

Basically Lou is going about his day to day life doing what I said above: Being a 25-year-old American contemporary alcoholic Millennial Man-Child. Until he meets Marissa, who he totally falls for and is completely taken in by. Yet after they meet at Lou’s sister’s going-away birthday party (his sister is temporarily moving to London to be with her long-distance boyfriend), and he and Marissa go out dancing and drinking, she disappears suddenly. The rest of the novel is Lou’s tortured, pathetic, desperate attempt to find Marissa, convince himself she is actually real and not in his head, and become “happy.”

Back to my idea of dividing the book into thirds.

The novel is short, about 256 pages. Roughly the first 80 pages, for me, were very good. Andrew Boryga—author of the fantastic novel Victim, which I reviewed here—gave Muka an incredible blurb for the book. He mentioned the strong voice. And he’s right: Muka’s first 80 pages sucked me right in. The powerful voice. The prose style which mostly consists of short, to-the-point, minimalist-Carver-style lines. The incredible humor. (He had me laughing out loud a lot.) Muka also does something which seems more and more rare these days in contemporary writing: He successfully nails down the male ego, the male mind, the male emotions, the male experience. And he pulls no punches. His novel is not politically correct, just as mine aren’t. And thank god for that! It made me respect the author and the writing even more. I believed him because his narrator’s thinking was so similar to my own thinking in real life when I was 25. It felt real, authentic, genuine.

The second third, roughly from page 80/100 to150/180 were, in my reading experience, his weakest. The struggle for any quality writer—and Muka is a quality, talented writer—is the dreaded middle. It’s hard to maintain interest in that muka-middle (pun for ya). And, for me, this middle section felt generally slower, anecdotal, repetitive.

I felt like, OK: Girls, booze, self-loathing, repeat. And repeat. And repeat. Ad infinitum. Honest truth: I almost gave up on the novel several times during this middle section. The desire to start skimming kicked in but I did my best to resist this urge. A bigger problem emerged for me, too: Though I was impressed with the writing, the humor, the dialogue, the authenticity: I didn’t care about Lou and his search for Marissa as much as I’d have liked to. And yet…something wouldn’t quite let me completely give up on the book. I wanted to care more, but Lou just felt too typical, too cliché, and too caricature-ish of a 25-year-old horndog-drunk American; it started to kinda bore me.

When, during this middle section, I kept asking myself, was something actually going to happen?

But then around page 170, 180—the start of the final third—the novel began to shift, moving largely away from both the muka-middle and the humorous, fun, easygoing first third. For the first time, the novel became quite serious, sincere and honest and direct. Vulnerable, one might call it.

On his endless search for Marissa, he at last begins to realize how selfish, lost and childish he is, and starts to consider the idea of quitting drinking (and coke, which is a major throughline). He thinks more respectfully and maturely about his parents, who prior to that he saw as mere interferences in his fun. There’s a really solid, touching, emotional scene towards the end between Lou and his father, where the generational gap and the different lifestyle choices and the disappointment by his father all sort of melts away and for the first time they truly connect. That was a powerful scene.

For me in this final third, and I have no idea of this was Muka’s intent or not, “Marissa” became a metaphor for sobriety, aka for the Finding of the Self. Finding “Marissa,” it seemed to me, was really about finding himself, facing his deepest fears, getting sober, turning his life around. In essence: Growing up. And he does eventually find her, and it turns out she was real all along. Another juicy realization I had while reading was that, throughout most of the novel Lou is trying extremely hard to find Marissa. He thinks if he can only get The Perfect Girl, if he can only get that external validation he so desperately [thinks he] needs, then, and only then, can he achieve happiness.

Yet it’s only when he finally lets go and accepts life on life’s terms—accepts things as they are—that Marissa actually, finally shows up. And this felt incredibly real, honest and compelling. It’s my direct experience. Whenever I try really hard to get something—a woman, a reviewer for my books, a friend, spiritual relief, happiness, you name it—the “thing,” whatever it is, always seems just out of reach. But, paradoxically, when I finally let go, set it aside and say Fuck it, and accept that things are As They Are…suddenly boom: The thing I want shows up. Or, something totally unexpected shows up…which ends up being way, way better than the original thing I thought I needed so badly.

Irony is a constant universal force in life, is it not?

Lou lets go and in doing so finds himself and “gets the girl.” The novel ends without the reader knowing if he actually gets and stays sober, or what happens longer-term with Marissa. But either way, we know Lou has had a deep and profound revelation, about himself, life in general, family, women and growing up. He is forced to face himself in the mirror and tell himself the truth. He is for the first time in his life enmeshed in what can only be called maturity. He thinks about other people, and about how he can help himself.

So, overall, I’d give this novel probably a 7/10 on a bad day and perhaps at 8/10 on a good one. It’s not a perfect novel, but of course no novel ever is. Having worked on the book for a decade does show, as far as the polished, gem-tight lines, the strong literary voice, the chiseled humor throughout. I just wish he could have gotten readers either more quickly or more entertainingly from the first third to the final third. Like I said: That muka-middle was, for me, slow; it sometimes felt like work.

Still, Muka clearly has strong writing chops. The dude can put down a line. Did I relate to Lou? Absolutely. He is many mid-twenties men, especially in the States.

Hell or Hangover reminded me of several books which I marketed as being similar to my own anarchistic drinking coming-of-age novel, The Crew: The Catcher in the Rye, Dead Poet’s Society and The Basketball Diaries. The Crew really plugs into all three of these. With Muka it’s closer to Catcher and Basketball, and less Dead Poets.

Some of the scenes in Muka’s novel almost seemed as if they could have come from my own novel. And my novel certainly includes humor, along with hard-drinking, wild anarchy, drunkenness, A Girl, struggles with and against parents and “the system.” But whereas Muka’s novel seems to rely more heavily on drinking, partying, humor and voice, The Crew shifts more deeply into meaning and depth.

In the end, I do recommend buying, reading and reviewing Alex Muka’s Hell or Hangover. It’s a good novel, in essence. I would have liked to have seen more meaningful action towards the plot in the muka-middle. I would have liked to get us more quickly, perhaps, from the first to the final third. And yet it was still worth the journey. Even through the slowest parts of the novel, I never fully stopped wanting to know how it would end. Would he at last find Marissa? Would he fully change, metamorphose into a better, more sober, more mature, adult version of himself? Because he does start to change slowly as the novel moves on. And change for the hero is crucial for any quality novel. Lou does change.

Novels are hard to write. The easy part is that first draft. That’s the only time you really get to just go. After that it’s an endless cycle of editing, receiving feedback, revising, editing again, taking a break, coming back to it, etc. It’s an exhausting experience filled paradoxically with joy, artistry, and much pain and frustration. Your first novel is your baby, which you birth after letting it gestate arguably your whole life up until the point when you write and then finally publish it. I respect Muka for his ten years of working on this piece of rugged art. It’s no easy task. He chiseled out a very promising first literary throw out into the epic cosmos.

The only question is: What will his next novel be about?

Buy Muka’s Hell or Hangover HERE.

Appreciate the honest review man!

Good review, Michael. Your endorsement is valuable because you are always honest about books you do and do not like.