Brandon Taylor’s The Late Americans: A Critique

The Millennial Author’s 2024 Failure

NEW SECTION ON MY STACK FOR BOOK REVIEWS, FOLKS!

~

Make sure to check out my new podcast, Sincere American Podcast covering the writing process, sobriety/recovery, being an American expat in Madrid, and the complex topic of masculinity.

~

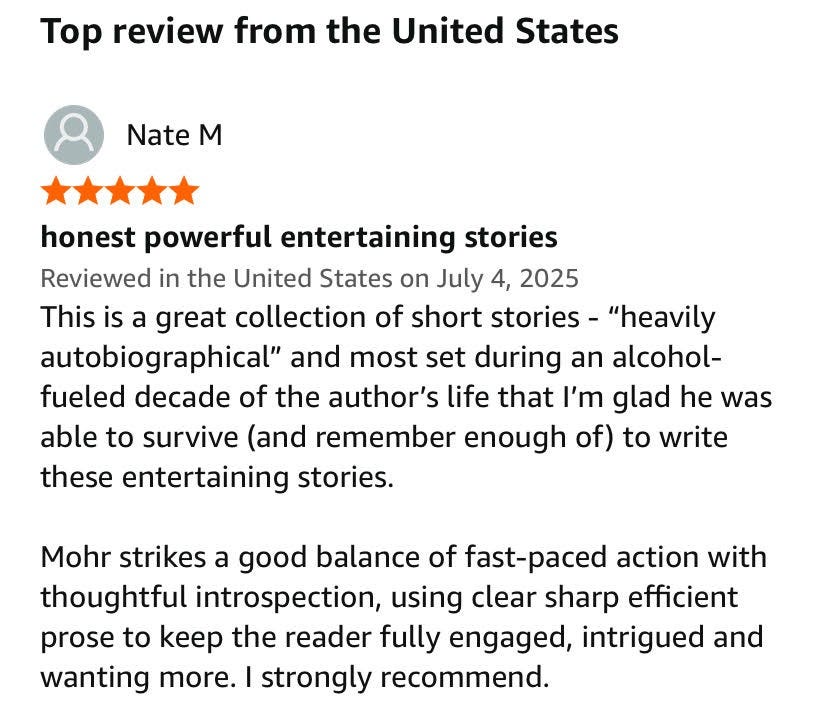

Buy MY books HERE. See below my first review from my new short story collection:

Read my previous Brandon Taylor review HERE.

Amazon summary of The Late Americans: In the shared and private spaces of Iowa City, a loose circle of lovers and friends encounter, confront, and provoke one another in a volatile year of self-discovery. Among them are Seamus, a frustrated young poet; Ivan, a dancer turned aspiring banker who dabbles in amateur pornography; Fatima, whose independence and work ethic complicate her relationships with friends and a trusted mentor; and Noah, who “didn’t seek sex out so much as it came up to him like an anxious dog in need of affection.” These four are buffeted by a cast of artists, landlords, meatpacking workers, and mathematicians who populate the cafes, classrooms, and food-service kitchens of the city, sometimes to violent and electrifying consequence. Finally, as each prepares for an uncertain future, the group heads to a cabin to bid goodbye to their former lives—a moment of reckoning that leaves each of them irrevocably altered.

A novel of friendship and chosen family, The Late Americans asks fresh questions about love and sex, ambition and precarity, and about how human beings can bruise one another while trying to find themselves. It is Brandon Taylor’s richest and most involving work of fiction to date, confirming his position as one of our most perceptive chroniclers of contemporary life.

~

This has got to be one of the worst novels (Brandon Taylor’s The Late Americans) I’ve ever read. Top Ten of Worst Novels, at a bare minimum. Read my previous review of the book when halfway through HERE.

I’m not sure what annoyed me most. Was it the blatant ideological progressivism which pulsed through the novel in such an obvious way that it felt like Orwell were smiling over my shoulder? Was it the lack of any coherent plot to speak of? Was it the boring, stale, 2-D characters who I didn’t really connect with? Was it the short, choppy literary style which felt stilted, repetitive and like TikTok writing? Was it the way that, just like Emma Cline’s 2016 The Girls, the traditional literary world fawned over this gay Black Millennial author’s novel claiming it was the next X Y Z only to be largely panned by gaslit readers? Or something else? A mix of all?

Who the fuck knows.

I almost feel a little angry at having bought this book, for eight euros, on my recent Paris trip.

Look, as I said in my previous essay when halfway through the book: Taylor does have chops. He can write. Sometimes beautifully. There are some deep insights, some revelatory understandings, some nuanced character studies which are strong. Taylor knows how to slice and unpeel deep emotional realizations and feelings, and how to analyze social situations in a compelling and interesting way. There are fragments in the novel which are borderline profound, even close to masterful, as I said in my earlier essay on the book.

But.

Some problems. First, the lack of plot. Look, I am fine with reading strong character-driven literary novels with little or even essentially no plot. Franzen, for example. Some of Dave Eggers’ fiction. Miranda July. Sally Rooney’s Intermezzo. My old literary hero Jack Kerouac’s classic On the Road. Etc. Fine. But the bar is very high for this type of writing. You’ve got to replace No Plot with Incredibly deep, rich, relatable characters. And in this regard Taylor fails dismally.

His characters, first off, in the grand arc, in the final analysis, don’t feel fully fleshed-out. I discussed this also in my previous essay a bit. He gets close with a few of them at times—Seamus, Bea, Ivan—but in the end I never felt like I truly knew these people in any real, true sense. They still carried the whiff of caricatures. Also it was strange: Fatima, for example, is a character we lightly hear about and see throughout, but don’t actually get into her POV until the last 100 pages, and we don’t really know who she is, why we’re in her head, or why we should care. Bea, too, a character I actually sort of got into and liked, was not even mentioned as a major character on the back of the book, which seemed odd. Too many POVs, and not enough of them felt crucial or even, sometimes, relevant.

Also, it has to be said: The sex. My God there is a LOT of sex in this book. Gay sex. (That’s another thing: Almost every character is gay, which felt homogenous, one-sided, not diverse, and unrealistic.) And the sex is often pretty detailed. I have no problem with sex scenes, and I don’t care what the characters’ sexual orientation is. But by halfway through the book I started rolling my eyes when it became, once again, clear that two characters were obviously, yet again, going to fuck. It’s like, Ok, we get it, young people fuck; can you focus on something else?

This novel is 300 pages. The final 100 pages are brutally boring, solipsistic, narcissistic, navel-gazing and slow. I started feeling the need to skim pages more and more. I screen-shot some whole pages to show how myopic and boring and pointless they were. Just literally scenes of, for example, two characters walking around the grocery store talking about basically nothing. Is this art? It often felt like literary diarrhea, like the loose, wet shit that most good writers would cut and remove when working on an early draft. Yes. That bad. (Not all of it, as I said, but much of it.)

It's also incredibly insular and navel-gazing in another way which adds to the irritation and boredom of the novel: It’s about writers and artists. Not only that, but kids in their early twenties, grad students in MFA programs teaching undergrads. The height of pretentiousness and a closed-off world that 99.999% of people in the world don’t care about and will never experience and which has very, very little to do with the Real Life most of us experience. Closed off, grad-student college life. Already for me a novel about writers is boring. It’s the anti-universal novel, focused not outward but inward. Knowing that Taylor did the Iowa Writers’ Workshop doesn’t help. It adds more fuel to the fire of irritation. Who is Taylor actually writing for? Elite grad students? It felt too much like literary masturbation. And Taylor comes on our minds, and not in a satisfying way.

There’s a moment wherein one of the characters (Seamus) casually mentions to another one that their poem was published in The Paris Review, his first published work, as if this were no big deal, as if writers outside privileged, expensive academia don’t work for decades trying (and failing!) to get published in venues like TPR. But this might be the existential sticking point for me, regarding the novel and Taylor in general, the thing which truly bothers me. It’s akin to the term “outsider art,” the idea being that The Academy, the MFA program, is “insider art” and everyone outside of that bubble, the so-called “autodidacts” are “outsiders.”

This idea repulses me for several reasons and on multiple layers.

The first reason is most obvious: Historically, way before MFA programs even existed, authors were “outsiders,” either not studying writing or not even doing or finishing college. From Goethe to Dostoevsky to Mark Twain to Henry Miller to Hemingway to Fitzgerald to George Orwell to Jack Kerouac to James Baldwin to so many more authors. And, ironically, particularly with Hemingway, what they study in MFA programs was once writers like these, and now is often about repudiating these authors (especially the evil and terrible Hemingway) and yet everything they study is built on the backs of these very writers. Everything you study in an MFA program today is a reaction to, a response to, a rejection of, a building upon, these “outsider” authors who came before. So this “insider art” is built onto the backs of “outsider” (read: authentic) “art.”

Also, the MFA is fucking expensive. Working-class people can’t do it unless they take out large student loans. I once knew a woman in Oakland a decade ago who was $80,000 in debt for her poetry MFA from CCA (California College of the Arts). Eighty-K for a fucking poetry degree!!! So, regardless of race or sexual orientation, MFA programs mostly consist of The Elite and The Elect (as John McWhorter calls the Millennial and Gen Z progressive crowd); the rich kids.

Yet writing has always been of the people, for the people and by the people. Again, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Hemingway, Faulkner, Henry Miller, Charles Bukowski, even Ray Carver, Denis Johnson, Kerouac, etc etc etc. (Even though yes, Carver was heavily involved in the creative writing academy, Iowa, etc. But his actual prose was for The People. He aimed at universality, as all good writers have and do.)

I think the truth is this: It’s the rich kid MFA students who are the true “outsiders” in the sociological sense. And their writing so often feels boringly mimetic, derivative and sadly, dumbly conformist. This is the case with Taylor’s work. Though, as I said, some of his writing is gorgeous—see some of the photos and quotes I add on this post—much of the story is lacking in real substance, real depth, real meaning, real poetic truth. The novel is aiming at something; it wants so desperately to show us the fracturing of youth, the end of one period of life and the inchoate beginnings of another, more mature side. But it doesn’t succeed in this endeavor. It makes it some distance towards the goal, but never ultimately lands. (Similar to Ross Barkan’s Glass Century.)

I want to discuss the syntax too, and the diction and the sentences and style in general. The sentence fragments started to drive me nuts. No subject-verb agreement, just fragmentary lines that begin and end in another beginning, like a closed circle whirling round on itself constantly. One, two, three-word sentences. Short, choppy TikTok lines. Like Sally Rooney. And this made me think of the phrase “program fiction,” because there are patterns you do see from these young MFA grads.

I saw this when I interned for a literary agent for nine months in 2013; there were always two ironic groups of submissions we received that were almost always universally bad: MFA grads and writing professors. Both assumed that because they’d spent a shit ton of time inside a classroom learning, teaching, unpacking and unpeeling stories and novels that, of course, their own work was bound to be good. The precise opposite was almost always true. Overwrought sentences, masturbatory, Carver-like mimetic minimalism to a degree which was laughable, $1,000 words seemingly inserted at random, and writing that felt so derivative of the 20th century masters that it was unkind to even comment about it. We rejected these, over and over and over and over again.

But this novel got through the “gatekeepers.”

Which brings me to my final and unpleasant but nevertheless necessary conclusion. Look, I will be upfront and totally honest with my biases and priors. We all have biases—especially those of us who claim to not have them—and unconscious agendas, regardless of age, race, sexual orientation, etc. (This is an obvious statement but for Gen Z and some young Millennials this notion needs to be pounded home again and again.) We wouldn’t be truly, fully human if we didn’t.

So here’s my biases. I’ll be honest, with this type of novel—shit ton of hype, praised by Emma Cline, Alexander Chee, fucking Oprah—I go into the operation with hostility. I wanted to find flaws in it, to not like it, to think it was weak. I did this with Sally Rooney’s Intermezzo and Miranda July’s All Fours…yet, as you can see if you read the essays, in the end I had to concede that there was much to respect in these books, especially in All Fours, even if I disliked the author and her overall goals and messaging. The quality of the prose overrode all of that.

Because, in the end, I may go in with hostility—not because they’re women or because Taylor is a gay Black man but because I tend to reject these kinds of new-age contemporary mimetic novels—but if the writing is fucking good, it’ll get my respect, praise and honest review. I am consistent with this. I go in mean but I am 100% open to being convinced otherwise, to being ultimately proven wrong.

But with The Late Americans I just couldn’t do it. It didn’t do the heavy-lifting required. A big part of me even started to really, genuinely want to love it so that I could, like with Rooney’s book, piss off more people on “my side.” (Which, theoretically, is the unorthodox, contrarian, “heterodox” side, but really I am a freak of nature and my own man and am politically homeless and truly have NO side at all.) This happened with Rooney: “My side” gasped, shocked that I’d give any respect at all to the terrible “TikTok writing” in Rooney’s novels. (Don’t get me wrong, there IS some of that.)

It’s very difficult for me, at this point, after having read the whole novel and looked a little into Taylor’s backstory, to not believe that at least a part of why he got an agent, got published, and has received so much over-the-top praise for this novel…is because he’s a Millennial gay Black man. How else, really, can you explain such a bad book? Let’s say any old WSM—White Straight Male—who was unknown had written this novel. Would it garner the attention of agents? Would it get published? Would it receive the same level of praise? Or even a gay white author. Would it? It’s extremely hard to believe that the answer to this question would be yes.

Of course there’s no way to ever find this out. And yes, as I already admitted, I have my natural biases. And yes, I have written about WSM in literature and how they’ve, over the past decade or so, been getting The Shaft in book publishing. So take everything I say with those biases and reservations in mind.

Still, though, what else can ever explain a bad novel? I would name some contemporary bad novels by WSM…but I don’t know any because WSM don’t get published anymore, or if they do they’re the sad beta males that don’t represent 99.999% of actual men on Earth. Dolly Alderton’s Good Material, a novel by a white British woman, which I reviewed here, was awful. Though I overall enjoyed Rooney’s Intermezzo, as a serious critic I also had many negative things to say. Ditto Miranda July’s All Fours.

I don’t give a shit what race you are, who you fuck, your age or wealth: A novel lives and dies by its own merit. I recently read and absolutely loved Richard Wright’s classic 1945 memoir, Black Boy. Though I disagree with his politics and world view, I loved Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me. James Baldwin I have always viewed as an absolute master, especially of the essay. I did a review here of I know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou. I love Ottessa Moshfegh’s work. Ditto Zadie Smith. Even some Emma Cline. Plenty of women and non-white authors. (And gay ones.)

I mention these authors and titles only so you’ll (hopefully) understand that it’s not as if I’m some WSM bigot who only reads books by WSMs (oh, there aren’t any in contemporary writing!) or by white men or by white people in general, etc. I love good writing, and that spans across all the silly, superficial barriers we humans love to create and reify, whether it be race, ethnicity, gender, class, age, etc. (All that shit is meaningless to me anyway except as bland sociological markers.)

Brandon Taylor’s The Late Americans doesn’t fail because he’s a gay Black author. Or because he’s a millennial author. Or because he’s American. Or because he’s an MFA grad.

The novel fails because it’s not a very good novel.

Period.

You're calling balls and strikes as you see them. Also, you're criticizing the book not the person. A differentiation that is so often lost. There are many authors with different books that either bored or thrilled me.

I love this review. Made me laugh. Also makes me sad that you have to explain your critique with so much social context. I understand why you had to do it, but it's a shame nonetheless. Speaking of extraordinary books with no plot--have you read This is Happiness by Niall Williams?