Setting aside the axiomatic absurdity of this idea, I can assure you that artists—and writers in particular—regardless of race or gender or national origin most certainly are our own species. I mean we’re human, of course. But I think most serious, driven writers and artists know exactly what it’s like to feel like an unheard insect which no one seems to understand.

~

Franz Kafka was a Jewish Austrian Czech author born in Prague (Bohemia) in 1883, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (Czech Republic after World War I). He died in 1924, in Austria, at the tender, shocking (given what he produced during his life) age of 40.

Famous for novels such as The Trial and The Castle he was however most known for his novella (or one might call it simply a very long short story; 50 pages) The Metamorphosis (almost certainly a reference to Ovid’s tale, The Metamorphoses).

Kafka’s life story reminds me a bit of the 19th century artist Gauguin, who I wrote about here. Gauguin was a tortured, dedicated, passionate artist who happened to also be, for a long time, a family man with a wife and kids who worked in the French stock exchange, until he fled all responsibility to focus exclusively on his Art, eventually ending up living with the aboriginals in Tahiti, married to a 14-year-old native girl.

Kafka’s life was much more regional in central Europe and not as intense. Nevertheless, Kafka worked in employment and workers’ comp insurance for a long time; he in fact was hardly known in literary circles in his own time and never made a splash. Only later, due to his close friend and literary executor, Max Brod—who Kafka told to burn his manuscripts; thankfully Brod rejected this request—did Kafka’s work become more known, respected and popularized. Now he is of course considered one of the most distinguished authors of the 20th century and his stories still hold powerful, universal appeal today. (I would argue Kafka’s work is even more necessary now, in our historical time of spiritual anxiety and destitution given the lack of face-to-face human connection and social media, polarization, etc.)

Kafka was certainly a writer of the existentialist vein, though that word wouldn’t be popularized until Sartre after World War II in the mid-1940s. If Kierkegaard in the early 19th century might be considered the King of Existentialism, and Dostoevsky the Prince, then surely Kafka is the brilliant Joker who bridges the two and brings us all the way to Sartre and Camus. Themes of faith, alienation, anxiety, death-fear, being different from others, internal crises connected to understanding our own inherent weaknesses and ephemeral reality, fear of true intimacy, amorality, etc, abound in all these authors’ works.

I recently picked up a copy of The Complete Stories of Kafka (1971), with a foreword by John Updike, from Powell’s on Hawthorne here in Portland. In the past I’d read The Trial, The Castle, The Metamorphosis and various stories. It had been many years, however. I’d read The Metamorphosis probably three or four times over the decades. I am now about 250 pages into the collection, a little over halfway through. *(Now finished, 2/28/25)

That’s one of my favorite things about books (or any artform, really): They remain the same, externally, but they always change for you, internally, because as you grow and change the contents of the books and stories change in your mind as well because you see them differently, consequently from a new and more mature perspective. Things you may have missed before suddenly show up out of the blue. It’s a fascinating process.

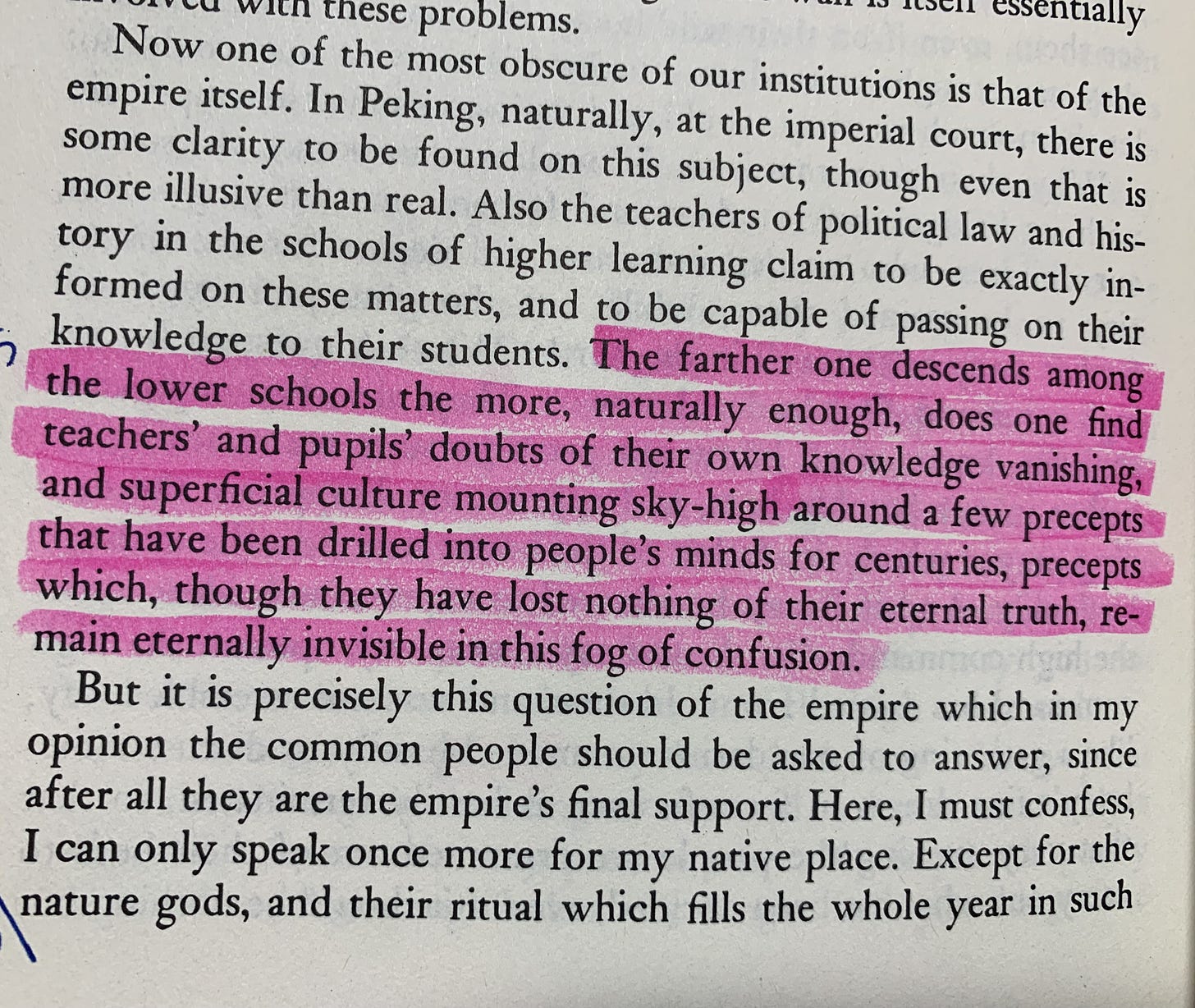

The first thing that struck me about the stories is that the writing is incredibly clear, engaging, usually quite basic and that most of the stories provide a juicy plot and a lot of scenes. Already this is counter to the way I remember Kafka, which was, like many of his complex themes around endless bureaucracy and never arriving at the protagonist’s goal, a more arduous and slow-going reading experience.

But this turned out not to be true at all! Actually, so far most of the stories are quite fun to read! He would pass Orwell’s Six Rules for English Language with flying colors. Many stories I found externally riveting; they had me right on the edge of my seat the whole ride. And he’s clearly trying to communicate and connect with the reader; he isn’t going out of his way to “sound like a writer” or to obfuscate understanding via big words (although some stories do drop some big words).

Probably the most affecting story, for me, so far, has been In the Penal Colony, an amoral tale about one officer’s joy at his torture machine as he shows a foreigner how the machine works prior to putting a probably innocent man into the machine. (The “condemned man” did really nothing wrong. There are strong echoes in this story of the later brilliant existential novel, The Stranger by Camus.)

But I was almost equally taken with my reread yet again of The Metamorphosis. Usually in previous readings of this 50-page story, I’ve come away feeling intrigued but sort of confused and not at all certain what the “takeaway” was. Now, that’s one thing about Kafka’s work: There usually isn’t a takeaway. There is no essential message, necessarily. No moral case is being made. No political message conveyed. It’s more feel and intuition above all else. And deep themes.

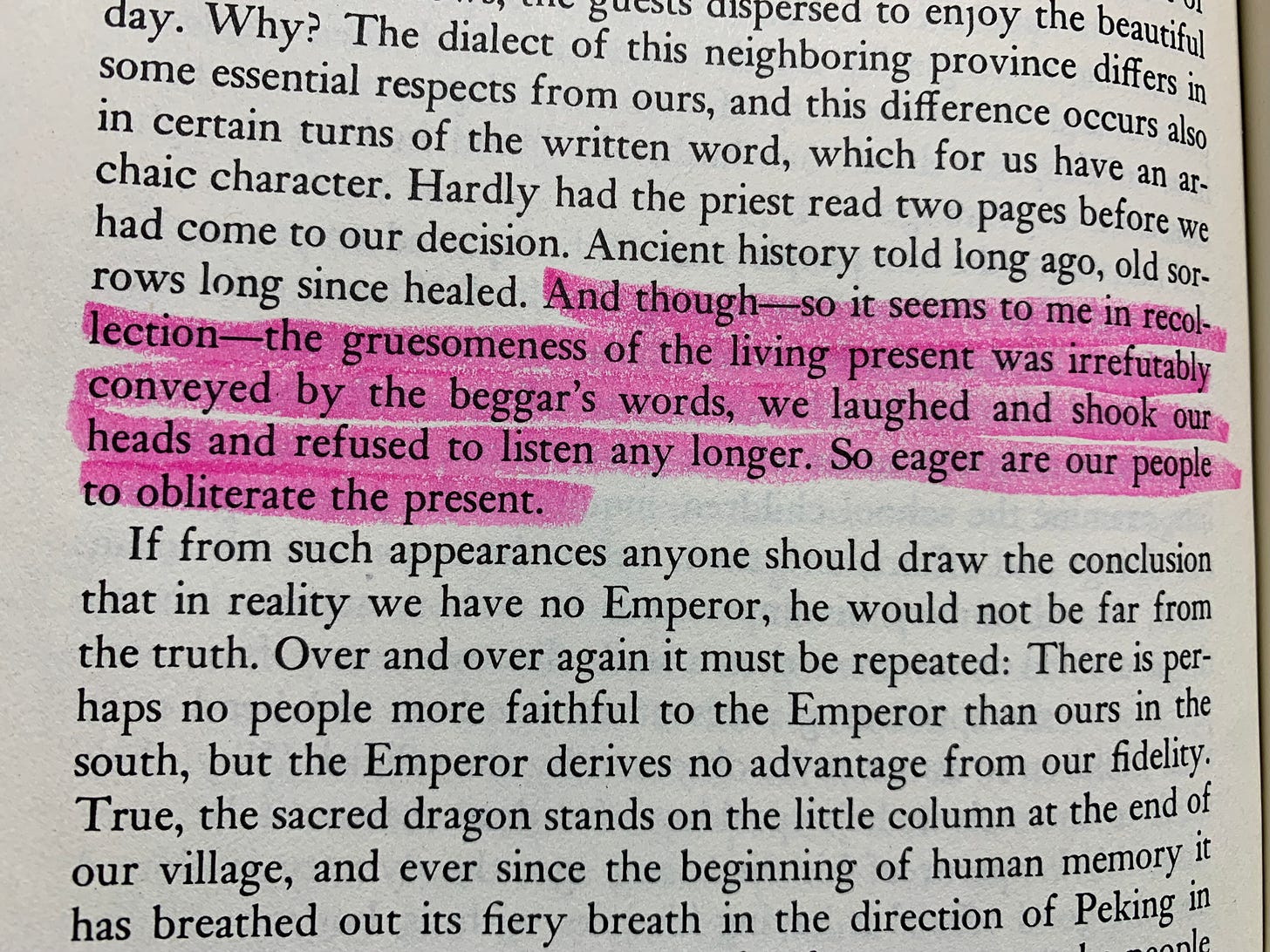

In almost every Kafka story so far, you see trends. Each story drops us into an already occurring scene (in media res) or else just starts explaining something from out of nowhere, but Kafka generally doesn’t do setting-prep. In other words, he doesn’t tell us exactly who the narrator is, where they are, what they’re doing and why. We’re just sort of dropped into the pot and, like crabs in slowly boiling water, we have to figure it all out as we go (and often we never do fully “figure it out”). Therefore, there is a sort of vagueness to it all, an abstraction, a mystery which can never be fully solved. (Isn’t this often like life itself?)

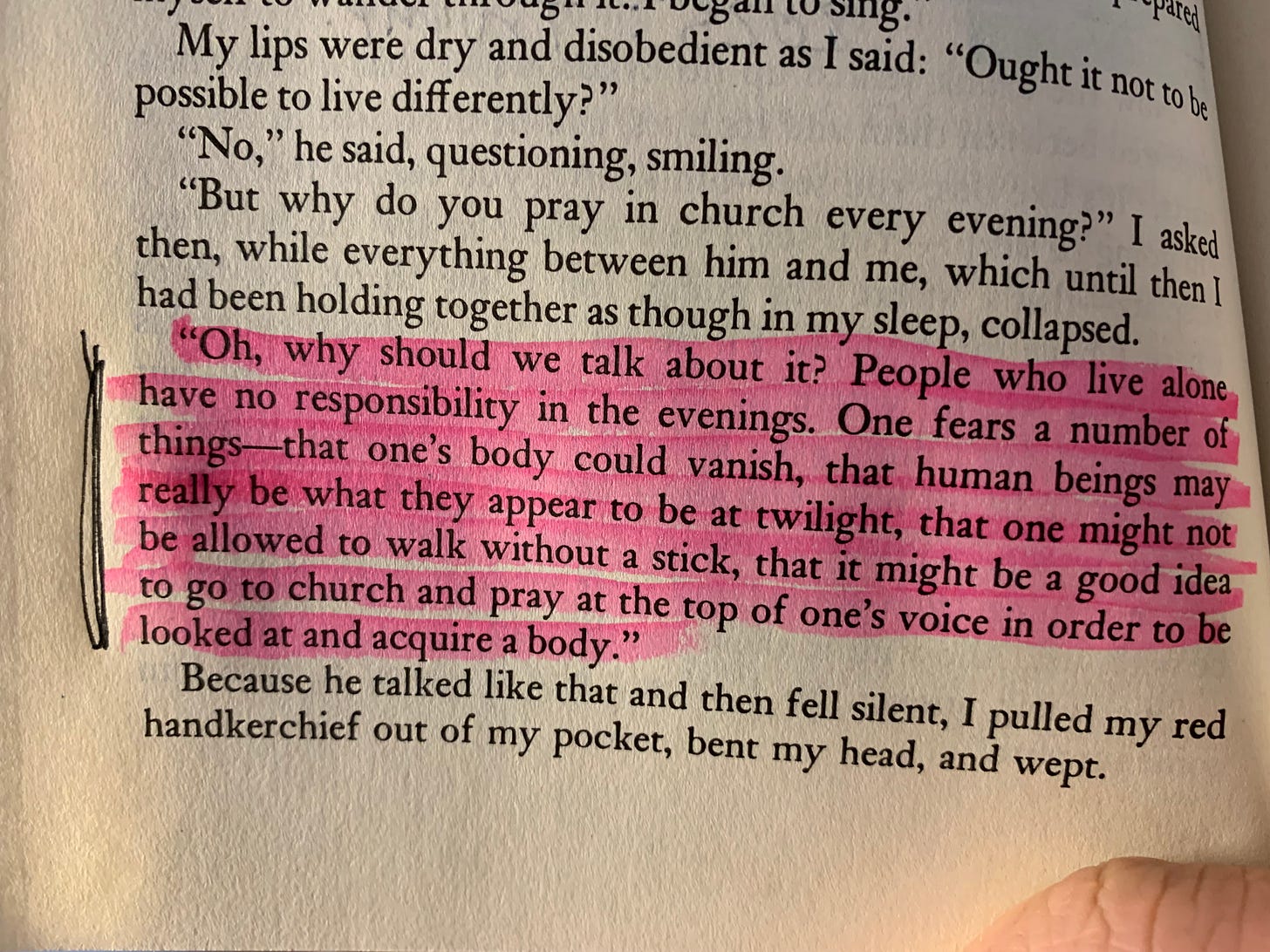

The narrator is often engaged to a woman and not married. This is because Kafka, in real life, was engaged several times but never actually married. (Which also again reminds me of Kierkegaard, who was once engaged and, for the “sake of philosophy,” broke the engagement and never married.) The narrator is often full of some kind of anxiety and feels misunderstood in some fundamental way. Often two characters engage with each other in a way that feels quite supernatural, beyond human in some way, or at least fairly nonsensical. Kafka was a surrealist writer, of course, so often you get a realistic story dotted with unrealistic moments, experiences, occurrences, etc. (Such as a man’s acquaintance who follows him out of a restaurant into the night to discuss the deepest feelings of his life, or, more radical, a talking Ape.)

There is always an “acquaintance” involved in the story somehow, which seems also true to the real life of Kafka. He worked and he wrote; his writing was always the brightest passion and he struggled constantly to get time to work on his stories. It’s a tragedy, I think, that he even had to work some dull, dead-end shitty insurance job at all, though sources claim he actually enjoyed his work and had friends there.

The Metamorphosis, I realized upon this reading, is about Kafka himself; ironically, it’s probably his most “autobiographical” story. Ironic, of course, because, if you know anything about the famous novella, you know that it’s about a narrator named Gregor Samsa who literally wakes up one morning in his room to discover that he has turned into a giant beetle. (Actually we don’t know for sure if it was a beetle or a cockroach or some other insect but based on descriptions and hints in the story, and based on thoughts by others such as Vladimir Nabokov, it seems most likely that it was some sort of giant dung-beetle.)

The story was written in 1912—when Kafka was about 29, 30—and published in 1915. The basic premise is very simple: Gregor Samsa, a traveling salesman who lives in a room in a house with his younger sister and their parents (working to pay off his parents’ extreme debt) wakes up one morning alone in his room having literally turned into an insect. (A large one, almost human size.) Disgusted and terrified, his parents reject him. His father tries to harm him, though Dad doesn’t see “him” as him, his son.

The mother is terrified and stays away. Only the sister is kind and feeds him scraps of old food and tidies up his room. The family is forced to work and take on boarders to survive. Days, weeks and months pass. Eventually Gregor can be in their presence (the family not the boarders) but it’s still awkward and uncomfortable. Finally, starving himself, Gregor dies. The family is free; they rejoice and have closure and can move on. At the very end, the parents see the physical and inner beauty of the younger sister and view her as their future and way forward. She has replaced Gregor.

It's a very sad story. We spend a lot of it inside Gregor’s insect and yet all-too-human (to use a Nietzschean phrase) mind. The most tragic reality is that, though Gregor can hear everything and understands everything his family says, and he can think normally and speak out loud, when he actually speaks it comes out as nonsensical noise to them. In other words: Communication is impossible. It might be akin to speaking two completely different languages and trying to communicate, but without the use of an iPhone, Google or the internet in general. If only Gregor could puncture this wall of confusion, this Tower of Babel. But he can’t, and therein lies the farce, the harsh satire of it all.

I know that in Kafka’s real life he had a very challenging and identity-defining combativeness with his strict, authoritarian father. Dad never accepted his son. Kafka, like all writers, was highly intelligent, creative, deeply sensitive, needy and intense. This in a time where these traits were not exactly normalized or encouraged. (If they even are today, in 2025.) Life back in those days—in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—was all about practicalities: Work, income, marriage for the dowry, social class, starting a family, having enough kids so that if a few died you’d be alright, etc. But this was not in Kafka’s fragile, genius nature. He was an author, through and through. Yet during his life he had to work in insurance and pretend he was like everyone else.

Thus the beetle is the way Kafka felt people in his circle viewed him: As a freak, a weirdo, a derelict, an outsider. Someone who didn’t care as much about the social niceties, the conventions one was required to follow to appear “normal.” He was alienated as an artist; people viewed him as some sort of psychological, metaphysical, metaphorical insect. He felt locked into the small, cramped room of his mind. Totally rejected by his family, and in the story—as in real life—especially by his irate, violent father. He is seen as subhuman, subnormal, subpar, a failure.

When he speaks it comes out to them as garbled chaos. There is no communication. He is alone in his alienation and anxiety. He dies horribly alone, too, starved. And this is true: We all do ultimately die alone, even if we’re surrounded by loved ones. Because to live means to possess a mind, and that mind logs off and we’re gone; there then is no more “we” left. There is no consciousness. Yet the people around us carry on, without our existence.

The horror of being an insect, then, was Kafka’s experience of being an Artist in the early 20th century in central Europe, a time when Art was appreciated but not artists themselves. (Still the case today.)

I can relate to being wholly misunderstood. People talk in contemporary times about being a certain race or gender or being fluid and how that makes one lonely and feel alienated, different and alone. Supposedly, if you’re, say, a WSM (White Straight Male) you’ve never experienced this, evidently because all white people are the same and also because we “have all the power.”

Setting aside the axiomatic absurdity of this idea, I can assure you that artists—and writers in particular—regardless of race or gender or national origin most certainly are our own species. I mean we’re human, of course. But I think most serious, driven writers and artists know exactly what it’s like to feel like an unheard insect which no one seems to understand.

Take my life, for example. I am a WSM. However, I’ve never liked sports; ever. I don’t know much about sports and I don’t care to know. I find sports ridiculous. Waste of time. Most of my closest friends are women. I was always closer to my mom than my dad. So, growing up in Southern California, home of the Average Surfer Kid—yes, I very much was a surfer, and a competitive one, too—you can imagine what life was like for someone like me. Not “hard” exactly, at least not in any meaningful physical way. But often excruciating when it came to my inner world, and my inner world has always been the thing for me that really matters. (I often wonder if some people who seem very basic and average and just live the basic 9-5 life even have an inner world. I assume that to some degree everyone does?)

I was always an outsider—into skateboarding, surfing and BMX first, and then punk rock in high school—and I never fitted in. But even in the outsider worlds I inhabited I was seen even there as an outsider. In the punk world in my teens I never quite looked the part well enough; I was always straddling punk, surfing and my own weird unique clueless style. I was an inchoate writer but I didn’t know it then. Alcohol saved me (at first) and became my manic survival medicine. I became a sort of crawling, chaotic insect in many ways, drawn mostly to sex with random women, numbing out, being alone, and feeling lost and depressed. The world, it seemed, couldn’t hear me, couldn’t even see me, and to the extent it did see me it didn’t view me as fully human.

I’m not suggesting any human being ever actually said that to me; I’m saying this is how it often felt back then, in my teens and twenties. I spoke a different language than others, the language of intensity, vulnerability, getting too deep too fast, being emotionally needy, chasing the capital-T Truth at the expense of everything else. Punk rock and alcohol did help me: They opened up an aperture in my universe which allowed me to come to violent terms with The Way Things Are.

I think I’m still on that journey. It’s a lifelong journey.

Kafka—a man who died two years younger than I am now, before the second world war, before even the Great Depression—was living in a much less tolerant society and time than we live in today. If EYE felt the way I felt growing up as a kid and teen in the 1990s and early 00s, I can only imagine how he felt at the turn of the 20th century.

In short: Every writer, every artist, at a minimum should read Kafka, especially The Metamorphosis. Every human being goes through a period or through moments of being misunderstood, perceived in a way that you do not intend, seen by others as freakish, alien, different, weird.

Kafka simply distills the feeling into one compressed, dissonant note. And that note crashes down on us now just as much as it should have in his own life.

He died of Tuberculosis, which, in 1924, we did not yet have a cure for. Another tragedy of epic proportions.

This is fascinating! I read The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka in high school (many years ago), and I remember being completely absorbed by the story and his writing style. What’s even more interesting is realizing how deeply the themes in the book—alienation, rejection, the struggle for acceptance, and rigid societal expectations, mirrored what I was going through at the time. Yet, back then, I don't think I knew I was Gregor Samsa, or even have the words to articulate those feelings.

It wasn’t until my 50s, when I wrote Unmuting Myself – A Voice Silenced by Doubt Rises to Inspire, that I truly understood why I connected so strongly with Kafka’s work. The universal experience of feeling unheard and unseen resonates in ways I couldn’t fully grasp at the time.

Your reflection on how books remain the same, yet change for us as we grow, really struck me. Somehow, the universe led me here, to this post, and now I feel drawn to reread The Metamorphosis—to see how it speaks to me now, from a new and more mature perspective. Thank you for bringing this story back into my awareness!