Karl Marx Revisited: Jonathan Sperber’s Book on the Famous Thinker

Jonathan Sperber’s Karl Marx: A Nineteenth Century Life

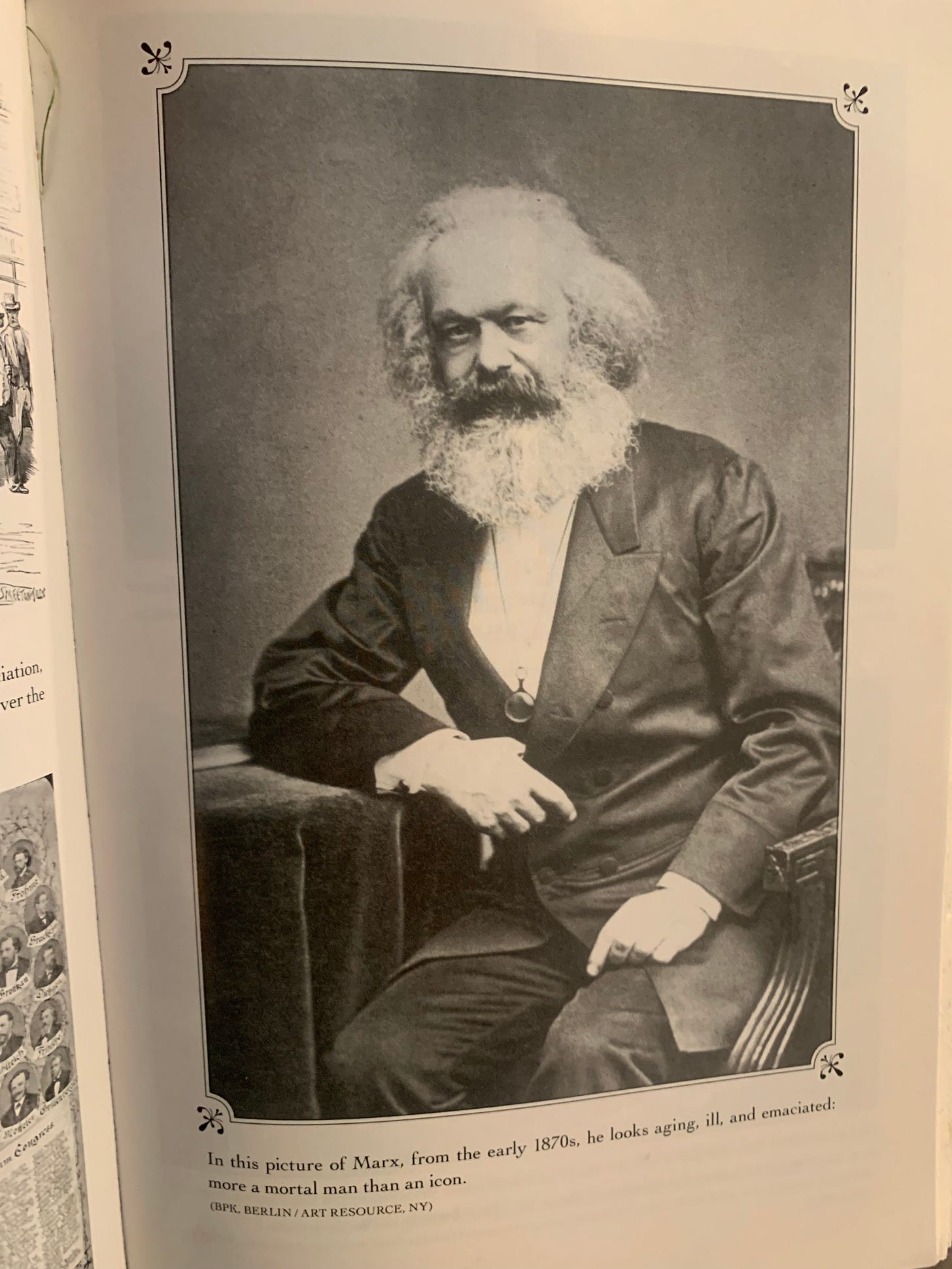

Recently, I finally finished the 560-page biography of Karl Marx, Karl Marx: A Nineteenth Century Life, by Jonathan Sperber (2013). A week or so ago I posted a short essay on this book when I was about halfway through it. Read that here. This will be the expanded, full “book review.” For more of my various book reviews click here.

What I came away with is the overall feeling that, like almost every famous thinker seen through today’s contemporary, exaggerated media prism, Marx was a much more complex and nuanced and intriguing figure in real life than he is portrayed now. He went through many phases and was not a black-and-white thinker, even at the end. Though I ultimately disagree with his renunciation of capitalism and his full embrace of a violent workers’ revolution, I also understand Marx through the prism—Sperber works hard here—not of 2024 identity politics and “pseudo” revisionist Marxism, but rather through the prism of the mid-to-late 1800s, in Marx’s own time. (Which is how we should strive to see all people; in their own time and not our own.)

Marx was born in a little town in Germany called Trier, in Prussia (northern Germany), in 1818, at a time when Germany was not yet united (that wouldn’t occur until Bismark’s actions in 1870/71), and the nation was instead chopped up into little individual and separate city-states and were ruled by autocratic kings and emperors.

Marx was of Jewish ancestry. His grandfather had been a rabbi. His father—a celebrated lawyer—had converted from Judaism to Protestantism, and Marx himself was baptized into the Protestant faith at the tender age of six. Jews were still discriminated against back then (until well into the middle of the 20th century and, sadly, are being savaged again today by both political sides, but more prominently on the fringe Left), so converting back then made sense. Protestantism—also a minority amongst the Catholic majority at the time—was the liberal Enlightenment groundwork for Europeans at the time. Marx’s father was left-of-center politically.

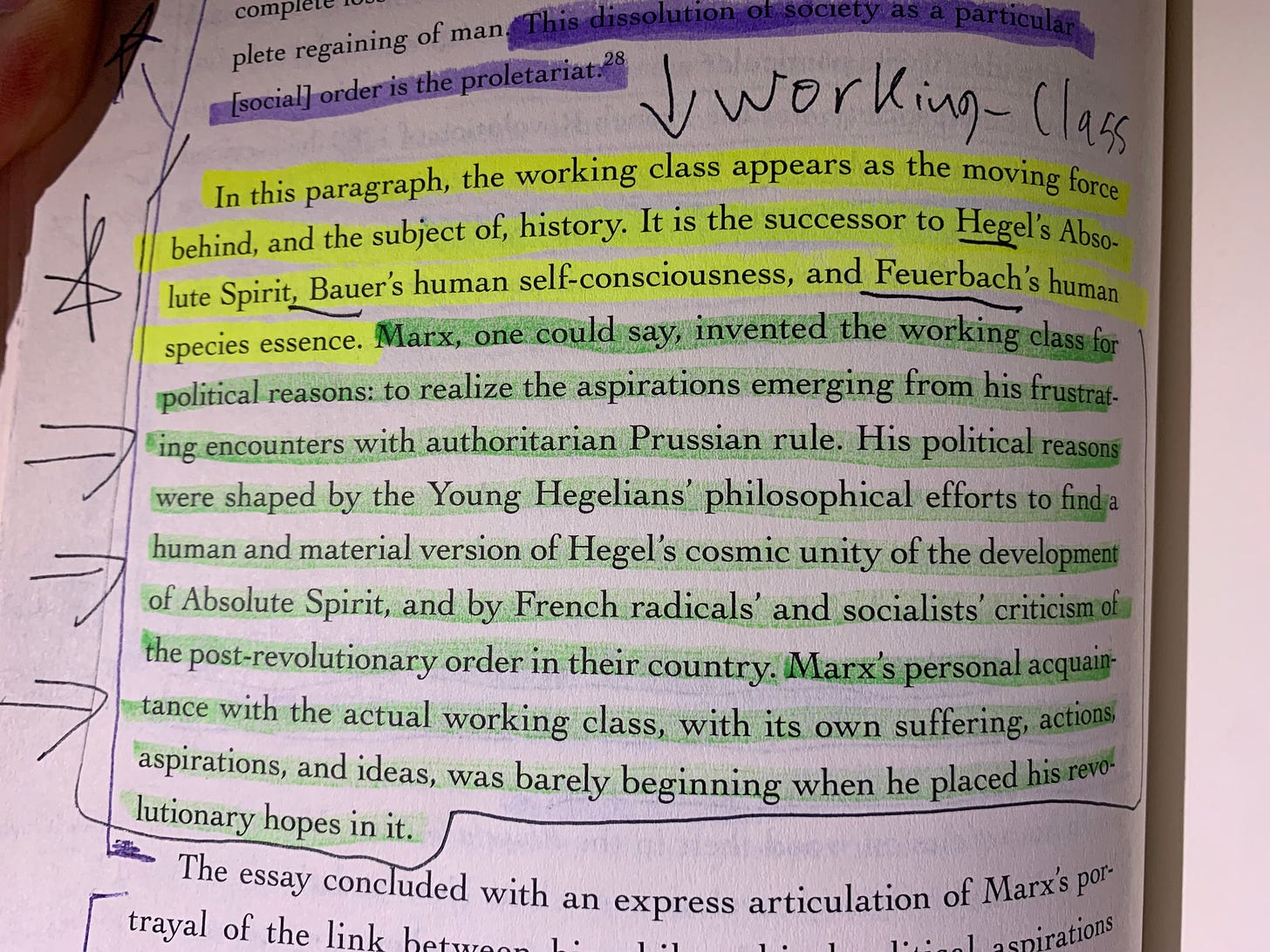

Later, Marx went to the University of Bonne and then Berlin, studying law but eventually switching to political economy/philosophy. He became fascinated with Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831), the famous and back then incredibly popular German philosopher. Particularly Hegel’s Dialectical Method shocked and altered Marx’s thinking. The Dialectical Method analyzed the disruptions, transformations and contradictions in historical processes. This method of thinking—for Marx connected always to capitalism, communism and economics—created the foundation of Marx’s polemics throughout his life.

He joined The Young Hegelians—who attempted to translate Hegel metaphorically in the decade following the philosopher’s death—but after a while broke from the group. The truth was that Marx was a conundrum, a bag of contradictions: Both a believer in capitalism as a first step towards eventual communism and as a violent revolutionary against capitalism; both a believer in liberal Enlightenment progressivism and yet also only as a first step towards socialism and communism; a believer in national independence for all nations and yet a believer that many subjugated colonies of, say, the British Empire (India, for example) were essentially inferior cultures and benefitted greatly from Britain’s western “civilized” society; Marx was arguably both a rabid antisemite and yet also a Jew and also believing in full Jewish civil rights; a hater of “bourgeoise capitalism” and yet in the end very much a bourgeoise capitalist in many ways himself; and on and on, ad infinitum.

In short: He was a full, flawed, complex human being.

When Marx was 20 (1838) his father died and he received a partial inheritance. For the rest of his days until her death in 1863—when Marx was 45—he would battle his mother for continual advances on that inheritance, usually receiving either very little from her or nothing at all. He’d been living in Berlin (in 1841 he received a doctorate in philosophy) but had moved to Cologne and it was there that he’d written for his first newspaper, The Rhineland News. He edited the paper for a while, and wrote numerous columns commenting on political philosophy and economy. During this time he became regionally known as a polemical, and thoroughly scrupulous journalist.

Marx’s thinking, besides Hegel, stemmed from the Utopian vision of the Jacobins during the French Revolution, especially and specifically the initial period of 1789-93. He felt that the French Revolution had basically been a revolution of the bourgeoisie against the nobility. Next, Marx felt, there needed to be a revolution of the proletariat (working classes) against the bourgeois. He understood the history of nations as having shifted from medieval feudalism to the sacrosanct rise of capitalism and private property. Marx wanted to abolish private property, the class structure, and the division of labor. He envisaged all people working as they pleased.

In 1848 revolutions broke out all over Europe. Most importantly, for Marx, were the uprisings in Paris and his local Cologne. He wrote feverish articles during these insurgent times, and called for violent revolution. He also wrote, during and immediately after, The Communist Manifesto, by far his most famous and most popular piece of writing.

The first line is as follows:

“A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism.”

Followed by:

“The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggle.”

Order was mostly restored by the kings of Europe, including in Paris and Cologne. Therein followed the Cologne Communist Trials. Many fled. Some were expelled from the nation. This was Marx’s fate. He fled to Paris, which had much looser restrictions on liberal notions such as free speech, freedom of religion, free press, etc. Marx, remember, was essentially liberal in his thinking at this time. True, he didn’t think that liberalism was the end goal. Liberalism and capitalism along with it would only be a first but necessary step towards socialism and then communism. But if he hated anything vehemently it was not so much liberalism as 19th century autocratic rule; aka emperors, kings and czars.

Marx had married Jenny Von Westphalen—ironically from an aristocratic family—at the age of 25 in 1843. She and Marx lived together in Paris for about two years, meeting and intermingling with German intellectual emigres and others from around the globe, enjoying the freedom to think, speak and write openly. Marx became steeped in revolutionary, radical thinking during this time. He felt that capitalism would more or less eventually destroy itself, due to it’s long-term (in his mind) inevitable decline due to a falling rate of profit, and the constant recessions and depressions which had and certainly would continue to strike at the flawed economic system.

The Prussian government went after him, even though he lived outside of Germany now, and eventually the French government expelled him as well. He and Jenny fled to Brussels, Belgium, where they lived for three years, from 1845 to 1848. In 1849—after the revolutions and the publication of The Communist Manifesto—Marx and his wife (and now kids) moved to London.

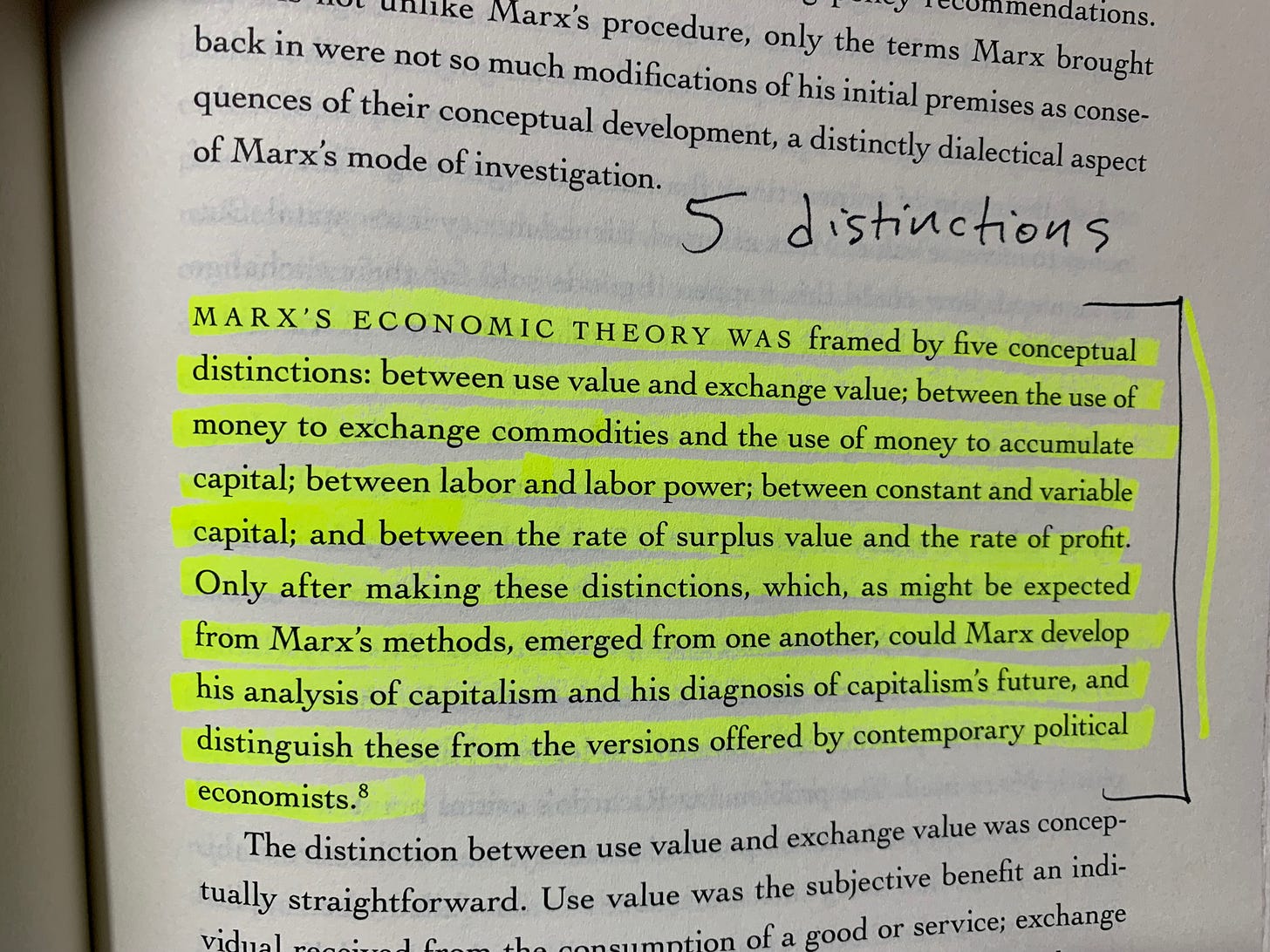

During all these years Marx was sharpening up his polemical ideas on his communist economics related to “surplus value” and “use value” and the “division of labor,” etc. He was writing about his [hopefully soon approaching] working-class revolution. He’d worked for half a dozen newspapers—The Rhineland News, The Franco-Prussian Yearbooks, The Free Press, Das Volk—and had been editor of many as well. He was gaining a name for himself. He became staunchly anti-Russia (under the czars), anti-Young Hegelians, and anti-private property.

London in the 1850s was a fascinating time for Marx, and a serious financial struggle. England was an intriguing choice and somewhat of a perfect yet ironic one. England was the penultimate Capitalist Nation. The British Empire possessed a massive amount of the globe when you factored in its many colonies throughout Europe, Asia and Africa. The industrial revolution was well under way in England. Mechanization was making work easier and faster for the owners of the means of production, but also making hours longer and more brutal. Many workers died as a result. (Read Dickens.) Working-class conditions were often atrocious. Capitalist owners made more money than ever while workers’ wages often stagnated or even fell. Soon they’d be partially replaced my machines altogether. Trade unions rose up to fight powerful corporations. Major newspapers such as the London Times, Daily Telegraph and The Economist also rose up during this era.

Marx and Jenny, however, were broke throughout much of the 1850s. Despite her background, Jenny had failed to gain a dowry. Marx had spent his meagre inheritance. In 1842 Marx had met and befriended Friedrich Engels (1820-95), a fellow leftist-socialist and writer/journalist/polemicist. Marx, only two years his senior, nevertheless became the younger Engels’ mentor. They formed a bond which stayed with them until Marx died in 1883 (age 64). Another irony: Engels took on his father’s cotton manufacturing wholesale business. A capitalist enterprise which produced a profit off of the cotton mostly extracted from the slave-produced American South. In turn Engels often supported his revolutionary friend Karl Marx with funds when he was low.

And Marx, often during his life, and especially in the 1850s, was often low on funds. He and Jenny were constantly in debt, sometimes having to sell items at the pawn shop and even write “begging letters” for financial assistance. They had several kids to support. They had to move many times while in London during this period, unable to continue paying the rent. Several children died (they had seven kids), including his son Edgar at age eight of a likely ruptured appendix in 1855. Marx even had some more conventional business opportunities but rejected them in order to continue pursuing his polemical, radical journalism, writing and thought. One might admire Marx’s passionate integrity, yet also severely reprimand him for failing as a man and father financially.

And here was another big irony: The man who was so [theoretically] unconventional, so anti-bourgeois, so anti-capitalist, was taking capitalist money from Engels to survive, was, despite his up and down poverty somehow managing to send his two daughters to private schools, was living a in many ways typical middle-class bourgeois existence as the patriarch of the family, the male head of household, even though he couldn’t always hold things together. There was a clearly defined familial social hierarchy. They lived often in “genteel poverty.” Debt wracked their lives.

Like his contradictory ideas of his own Jewishness, he argued for full civil rights and voting rights for women (and all people everywhere) and yet behind closed doors—with Engels, often—mocked women and firmly believed that revolutionary activity was a man’s job, not a woman’s. Women, in the same way Jews and Russians and inferior “uncivilized” colonial nations, were not fundamentally equal to men. (He also secretly impregnated his nanny.)

One could argue he was a deep antisemite and sexist and racist (he used “The N-word” writing to Engels sometimes when referring to American slaves and Africans), or one could argue that he was a more or less typical European living in the mid-late 19th century. Antisemitism, racism and sexism were unfortunately and sadly “the norm” at this time in history, both in America and on the European continent and elsewhere. This doesn't excuse Marx or give him a pass, but it does provide some necessary historical context.

There was also some ironic friction between Marx and Engels and the proletariat who they theoretically believed needed to at some point rise up and take down, via violent revolution, the bourgeoisie. Marx once referred to the working-classes as “knotheads,” aka basically idiots, to Engels. He was often frustrated by what he saw as the proletariat’s intellectual obfuscation, and lack of understanding. The working-classes, for their part, sometimes liked and sometimes loathed Marx. (Working-class union members once even chased Marx and Engels out of a communist meeting.) Many in the proletariat saw Marx as a sort of prophet, but many others saw him as a typical bourgeois who was all theory and no action. Marx was not one of them; he was a soft-palmed middle-class man who wrote articles and books and was supported by an industrialist-capitalist who made profit off the backs of slaves. In short: He was praised and mocked at the same time.

Marx believed economics was the main global driver of social change and social upheaval. This became a biological and mechanistic driver, for Marx, once Positivism took over during the 1850s, which began especially after Charles Darwin's groundbreaking On the Origin of Species in 1859. Positivism was the idea of moving from a historically backwards feudal society made up of religion and superstition, into a modern capitalist economy underpinned more by rationalism, empiricism and Enlightenment principles of liberalism, science and free thought. (After Darwin’s tract was published some toxic notions of “biological race” also rose up, with the dumb rise of pseudo-scientific “race theory,” which, among other things, saw Jews as a distinct and different biological group; ditto Slavs.)

What Darwin wrote about evolutionary biology became Marx’s creed about social movements driven by economics. (Marx greatly enjoyed, was influenced and inspired by Darwin, but also criticized many of the famous natural scientist’s ideas.) Marx saw social and economic movement as being driven largely by biological realities. Marx believed in Positivism, yes, but also believed in an inherent “inner logic” to movements, individuals and thinking in general.

Marx’s three main social-economic theories rested on this foundation of thought:

1. Productive forces

2. Division of Labor

3. Private Property

Marx saw capitalism as eventually failing due to the falling rate of profit over time, the fact that the owners would gain more and more profit while workers would financially stagnate and struggle as profits rose, thus leading ultimately to violent revolution via the proletariat.

Marx—another beautiful irony—was all about free speech and free press yet, according to many friends and family of the time, he was somewhat of a “personal dictator” who raged when anyone criticized his ideas. While publicly espousing his joy at divergent perspectives, he simultaneously felt angry at anyone who disagreed with him either privately or in print. Marx—like most [male] thinkers—had an ego the size of Texas. He even challenged enemy newspaper writers and editors to “duels” when he felt attacked. He did this in both young and older age.

He certainly felt he was some sort of genius and probably a social and economic prophet. He thought he could see into the future and, in some ways, he could. (He basically foresaw the 1917 Lennin-led Bolshevik revolution in Russia almost 35 years after his death.) Since Marx had too much pride to criticize his own [older, now abandoned] views, he did so by criticizing other revolutionary thinkers who made his own older points; he then claimed he’d never had those views to begin with.

Like the socialist and anti-Totalitarian writer and thinker many years later—George Orwell—Marx fought not only against autocratic emperors and kings (Wilhelm IIII; Napolean III), but also against his “fellow” (seemingly) socialists, communists, syndicalists and anarchists. (He was once friends with Bakunin, the famous anarchist, but later violently broke with him.) When Leftist French socialists in the 1870s started calling themselves "Marxists,” Marx himself said he was “not a Marxist.” Marx even believed in free trade…but again only as a first step towards revolution. (He also wanted, in the future potential revolution, to seize all private property and distribute it among the masses.)

Marx did, it’s true, come up with the lamentable notion of “oppressor versus oppressed,” which has now become en vogue amongst young Millennial and Gen Z so-called [revisionist] “Marxists,” an idea that unfortunately pits various “races” against each other and dismisses class altogether. Marx, of course, was exclusively talking and writing about class during his era, not race.

The German revolutionary émigré (Marx) had many friends but also many public enemies. He fought most of his public battles through newspaper print back and forth, each scoring political and social points for their side. Often he battled The Young Hegelians. He even argued publicly with other socialist and communist splinter groups. There were often secret communist spies who reported back to the emperor.

For a while during the 1850s Marx wrote for the American paper The New York Tribune. (A sizeable portion of the articles by Marx during this time were actually ghostwritten by Engels.) He hoped—but was wrong—that the global recession of 1857 would trigger a revolution. (Which makes me think of Hitler viewing the global stock market crash and ensuing depression in 1929 as a God-Send since it would (and did) push him up finally into horrible power.) He was a regular contributor and wrote, in that decade, hundreds of articles.

When the American Civil War broke out he sided with the Union (the North) and was fervently against slavery. (Many German and other European émigré communists moved to America later and fought for the Union in the Civil War, against slavery.) Marx was highly knowledgeable about American and in fact European and global history; he read absolutely voraciously. Marx during this period also lost his Prussian citizenship and became “stateless.”

In the 1850s three social upheavals occurred:

1. Crimean War with Russia, 1853-56

2. Britain’s Second Opium War with China

3. Indian Uprising against British Empire

Marx wanted to know what these occurrences as well as the 1857 global recession meant for global capitalism. Yet another irony: Contrary to *some* (but definitely not all) capitalists in the early 1850s, Marx *wanted* the western powers (Britain, France, Prussia) to go to war against Russia. (Marx was pro-Ottoman Empire, which was the empire weakened and therefore threatened by Russia.) He saw Russia as the biggest threat to global liberalism and the next stages leading to communism.

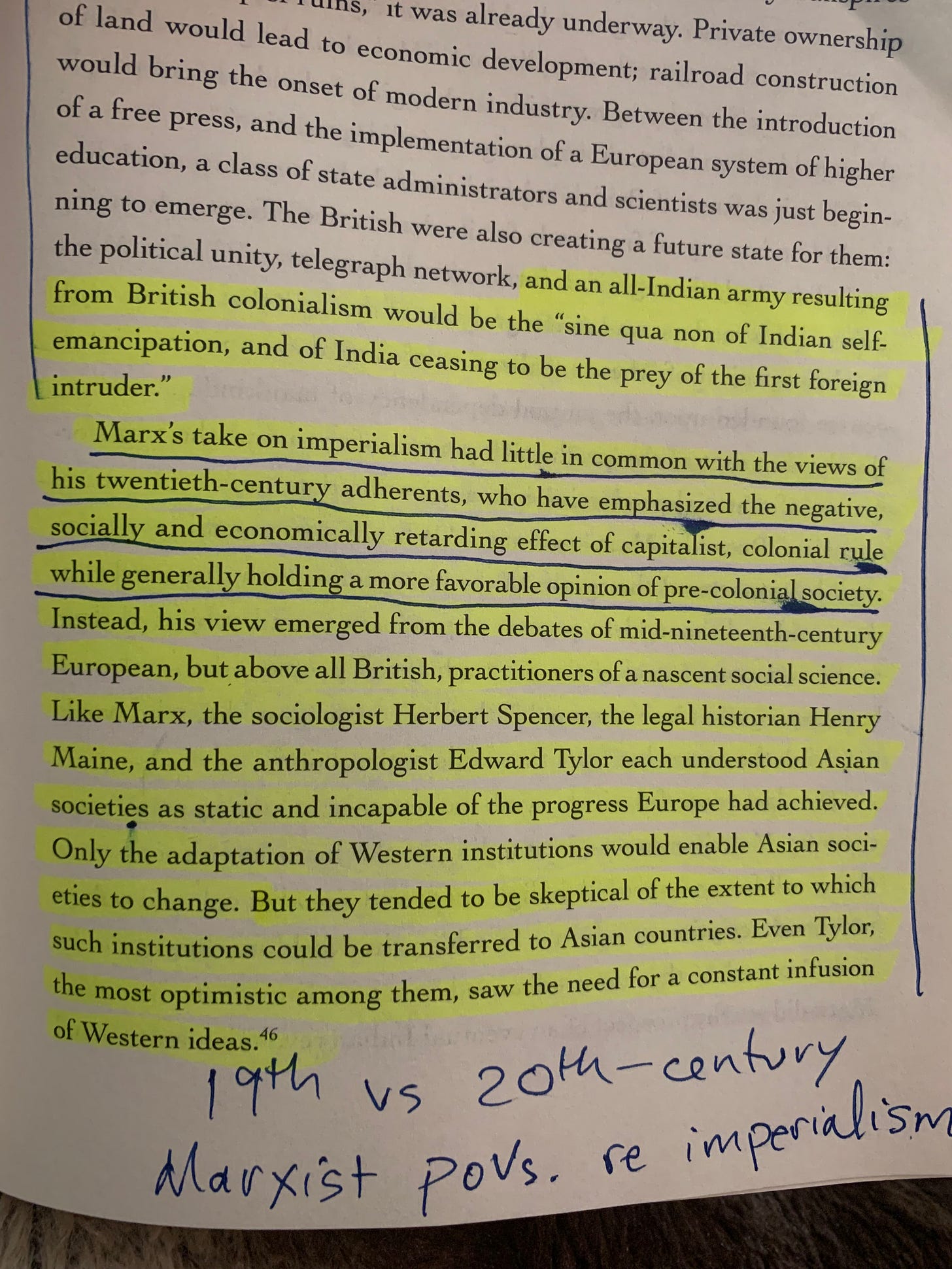

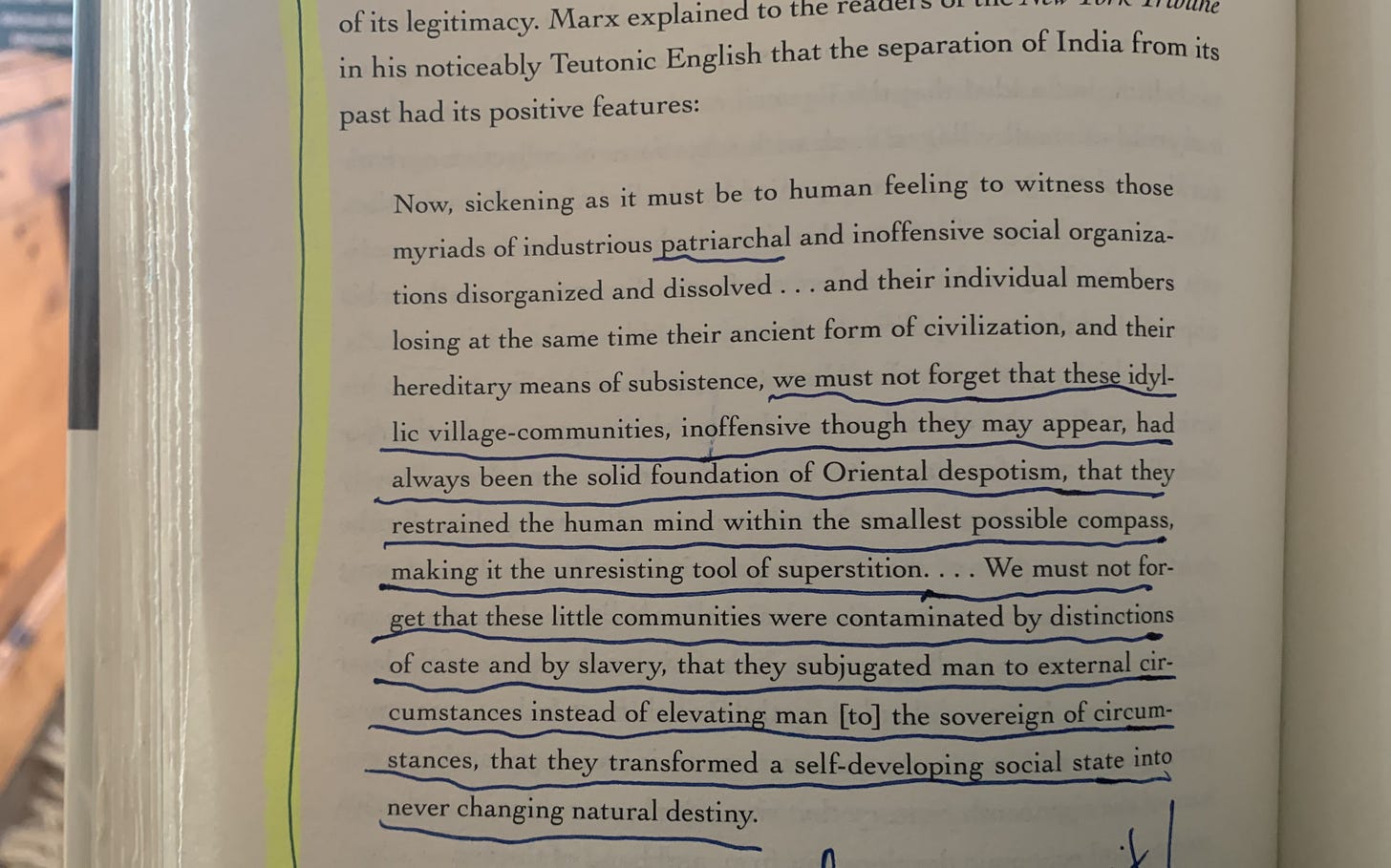

The Russian czar needed to be eradicated. Some capitalists Marx called “peace mongers” because these capitalists did *not* want to go to war for any reason. (He also, as I said in my previous Marx essay, felt that colonialism was flawed but in the end a net good for the colonized [especially] Asian countries since they were financially lifted up and brought into western “civilization.” He also saw Asian nations as “ideal” in terms of theoretical communism because they lacked private property and instead had property owned and run by the State.)

However, despite being “pro-imperialism” and “pro-colonialism” as it were, he also contradictorily believed in the national unity of nations such as Italy and Germany and Ireland.

Often he spent 12-hour days reading in the British Royal Museum library. He was obsessed with knowledge. He devoured Rousseau and John Stuart Mill and read (another irony, due to their classical liberal capitalist views) Adam Smith and his disciple David Ricardo. He studied ancient Greek history and thought (as he’d done in college and had written about his doctoral thesis, considering ancient Greek thought from a Hegelian Dialectical perspective), and read contemporary novels as well. He loved Balzac. He cherished Shakespeare. Goethe. Dante. Cervantes. Pushkin.

In 1864, Marx and Engels formed the International Working Men’s Association (IWMA), which was a loose affiliation globally of communists, left-wing liberals, socialist, anarchists and others who created an international correspondence, formed trade unions, and generally wrote and fought for the class struggle against the prevailing autocratic power structure. Marx labeled the IWMA the First International and headed the establishment.

The 1860s saw more European upheaval: Revolutions, strikes and uprisings around the continent (including Spain, Italy, France, Austria, Romania, Ireland), not to mention two wars: Prussia against Austria (1866) and Prussia versus France (1870). Bismark—seen by Marx as a conservative reactionary leader—surprised everyone by calling for war with Austria and for the national unification of Germany. Bismark even tried to get Marx to work for the State as a financial newspaper columnist; Marx declined. Bismark abolished the guilds and instituted freedom of movement and even shortened children’s working hours. Liberal reforms. By 1867 Marx had used up all his inheritance. He then fully relied on Engels who had also received his own father’s inheritance by then.

In 1870 Prussia defeated France in war; the remaining French National Guard rebelled and formed, for two months, a revolutionary government. This was called The Paris Commune. The French people fought for a republican government. They formed a new National Assembly, just like in the French Revolution of 1789. Ultimately the Commune made Marx and others (and revolution in general) look bad, a la nasty street violence. And yet at the same time the Paris Commune made Marx internationally famous.

Marx throughout the 1870s was writing the three massive volumes of [Das] Kapital, his gigantic treatise on economics. Unlike many famous contemporary authors—say, Stephen King or Jonathan Franzen—Marx did not have solid writing discipline. (Can you blame him with half a dozen kids, crushing debt 80% of the time, and his physical ailments?) Yet he wrote massive tomes, and hundreds of newspaper articles. His writing was not routine, nor regular. He often pumped prose for seven, ten, twelve hours straight at seemingly random times, often in the middle of the night. It was strange, erratic and wild.

During this time, 5-8 years before his death in 1883, there was a battle to the [metaphorical] death over the IWMA between Marx and his arch-nemesis, the antisemitic anarchist Bakunin, a one-time friend when younger. In 1872, Marx attended his first IWMA meeting in person. He fought hard for the IWMA and won, afterwards ironically (or not) dissolving the organization. Part of his legacy was dissolving it instead of allowing it to be manipulated in Bakunin’s hands.

Marx was still at this point strongly anti-Russian (under the czar). He was even pro-Tory, pro-Conservative when it came to being anti-Russia. Yet he increasingly began to view Russia as fertile ground for a people's revolution. The Russo-Turkish war of 1878 increased this feeling. The 1870s, as in the previous two decades, saw more recessions and economic downturns, yet no mass working-class revolution. The global colonial fight began amongst the major nations, especially over control of Africa.

Marx was against cooperatives and even state-sponsored free public education. He did not support farming and living collectives. After Marx died the ideology of “Marxist Revisionism” began. Lenin (1870-1924), the first revolutionary to actually implement (in theory) Marxist ideas, was a fervent “deviationist,” a propaganda peddler of his own unique brand of Marxist revisionism which served his exclusive purposes. Lenin used, abused and bent Marx’s ideas for his own rather dictatorial arc.

In America and abroad—but especially in America—the social, cultural and political ruptures of the 1960s changed things, particularly in academia. Since Marx’s time there’d been, in the United States, strong minority strains of Marxism, socialism and communism. We saw a lot of it during the 1930s under the era of FDR and the Great Depression, and again in the 1950s when it was largely (but not entirely) exaggerated by Joseph McCarthy.

But it was the magical, wild, Utopian 1960s and the post-war Baby Boomer generation who embraced a revisionist form of “Marxism.” Since then, Marx’s ideas have been more and more bastardized, until they were finally “purified” completely of almost all class issues—Marx’s entire argument—and replaced with racial, gender and other [superficial] identity issues. And then the term “Marxism” was mostly erased altogether and replaced by the broader term “progressive liberalism.” Yet Woke identity politics has little to do with liberal Democratic values. In fact these two are diametrically opposed on most issues. Culturally, the Democratic party has been captured by this young [mostly] white fringe element who dominate media. Somehow, it’s become the mostly elite rich white Millennials and Gen Z who oppress the working-class of all races in their fight “against” global capitalism (while they tweet their rage on their iPhone 15s).

It's become an absurdist joke, something out of a satirical Mark Twain or Orwell novel. I am not a Marxist. But I do see *some* basic value in *some* of Marx’s original ideas. Ultimately I disagree with Marx on his most fundamental notion: That capitalism is just a first step towards eventual communism, a “dictatorship of the proletariat.”

Marx forgets one key, crucial and frankly obvious reality when he theorizes about his ideas: He loses sight of the axiom of Human Nature. Humans, like our closest animal allies (genetically speaking), the chimps, are intrinsically hierarchical. We just are. It’s in our nature. It’s in the nature of all animals. It’s natural, normal and organic. You see it in the chimp community. You see it in almost all indigenous tribes. You see it in man going back to first hominids and the earliest agricultural villages 10,000 years ago. Capitalism is certainly far from perfect. Look no further than the history of the British Empire, the legacy of slavery, or the history of the American CIA around the globe, not to mention imperialism and colonialism in general.

But we saw the results in the twentieth century of communism: The Soviet Union; Cuba; Venezuela; China; North Korea; etc. The results were devastating. We need civil rights, such as freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of religion, the balance of powers, constitutions, self-determination. While capitalism has historically had some evil sides, it also signaled the quick (historically-speaking) end of slavery (begun in non-western nations such as Africa itself long before the rise of Western Democracies), the crushing in the middle of the twentieth century of the terror of totalitarianism (Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini), the ability for anyone anywhere to come to America (hopefully legally) and make a better life, global trade and defense agreements, a globally connected world, the rise of industry and technology, etc.

No political or economic system is perfect. No group or movement or individual is perfect. Like Marx wanted, we have to use a dialectical method of reasoning, between the extreme poles of humanity and politics, to end up finding the safe and healthy middle ground. Roughly speaking—and yes, even despite Donald Trump and this current polarized moment—this is, I still very much think, the ideal goal.

In some ways Marx had the right idea…at least when he was younger. Later his views became rigid and plastic. He grasped that liberalism was where we needed to build a foundation from. He was just wrong about moving “beyond” that foundation. We don’t need to move beyond it. We simply need to honor it and protect it and always work to improve it.

I think, generally speaking, we're doing that.

This is really fascinating, complicated stuff and I don’t claim to understand all that you’re reviewing here. But you magnify the point that the onus is on us to understand the history that has brought us to this point. So many people today don’t understand what capitalism really is, and condemning based on a one-dimensional perspective. The ideologies that we’re struggling with today are not new. If only we would stop and face our own global past in the rear view mirror, we might learn something. Teaching World History in our schools is as important now as ever.

Thanks for this, Michael.