Buk had a hell of a lot of self-awareness, which is also ironic. He didn’t try to hide the fact that he was what he was, which often was fairly despicable. He understood something lost, forgotten, but crucial about Art: it’s not about being “good,” it’s not about “community,” it’s not about any specific ideology (fuck off with your “literary citizenship”), it’s not about being safe or polite or kind. Art—true art—is an expression of the inner complex turmoil which is the Human Condition. Rarely can a writer truly “open up and bleed.” Were Buk a musician he’d surely have been Iggy Pop. (Perhaps a little closer even, at times, to G.G. Allen.)

Who hasn’t heard of Charles Bukowski? Madman poet. Drunkard. Short story writer. Autobiographical novelist. Lowlife. Barroom brawler. Even tortured, obscure genius.

Like many of my [Millennial] generation, I loved Buk. For a long time, frankly, I didn’t exactly know why. I’d always found it ironic that he was embraced—maybe no longer, given the age of Wokeism and #MeToo?—by the young Left hipster-intelligentsia circles who grew up, like me, in the 1990s and early 00s. These hipster types claimed to be about love and acceptance and feminism and community and inclusiveness, yet they read and cherished Bukowski, a man born in 1920 who often wrote nastily and brutally about “whores,” “cunts” and straight-up rape. (Seeing it, imagining it, doing it.)

Yet there does seem to be a deeper reason. Several, actually. First, at least the original “Beat” hipsters (read Norman Mailer’s The White Negro) were often white middle- and upper middleclass kids who faked being working class delinquents: Going to see jazz in the Village in rooms filled with Black folks, yapping about “the man” and “the system,” etc. In other words, the original hipsters came out of a sort of cultural stew made up of criminals, wannabes, intellectuals, jazz musicians, the middleclass, and people who wanted to be or organically felt “anti-authority.” It was about rebellion, communism or socialism (or at least being anti-capitalism and anti-imperialism), looking tough, appearing nonchalant, being cool.

Therefore, my point is, Buk was organically anti-authority, which is what attracts, perhaps unconsciously, largely white, largely middle and upper middleclass kids to his prose.

Also, Buk was against The Man. He was a socialist without being overtly pro-socialism or political at all. (Orwell would disagree.) Buk was a working-class author, perhaps truly the first one who fully embodied the down-at-heel blue collar man, the man who had only his body, his physical labor, to sell.

If you read his collected letters, or Notes of a Dirty Old Man, you’ll hear about working-class men (firefighters, plumbers, cops) actually reading his books. That’s rare. For one, this probably, speaking in generalities, isn’t the highest reading population. But more, for them to not only be reading but reading serious literature. (Some would quibble with calling Buk’s work “serious literature.”) That is a truly unique thing. (Even more so now, as traditionally published writing seems to be almost exclusively by elites, regardless of race.)

My point is that he appealed to a broad audience, especially those who weren’t in academia or the literary world writ large.

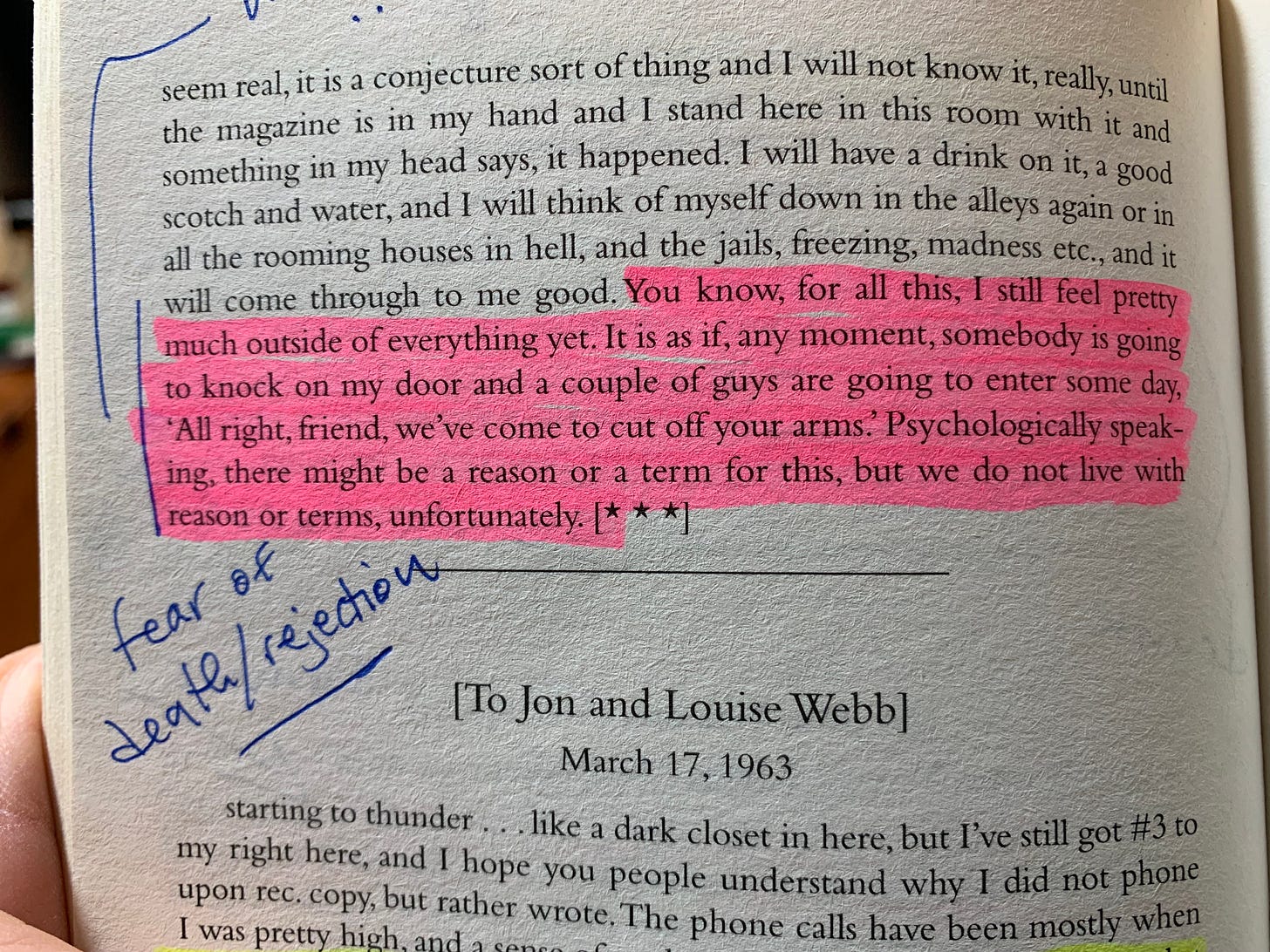

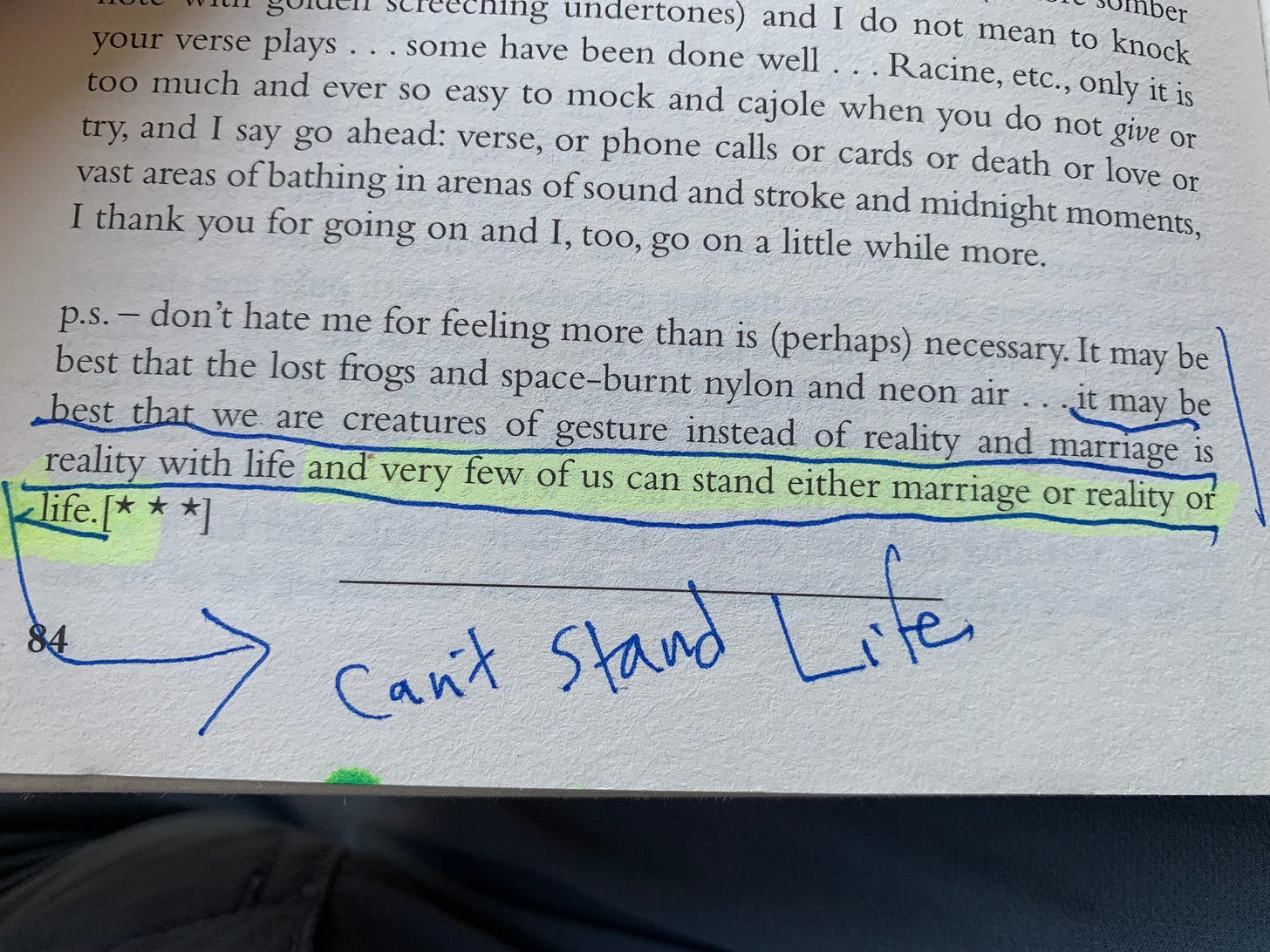

In addition: He’s an irony-machine, composed of sharp inner opposites. (And what is hipsterism if not the salty, cloying whiff of irony?) With Buk you had a man at once legitimately tough, down and out (one of Buk’s biggest literary influences, besides John Fante’s novel, Ask the Dust, was Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London), working-class, bohemian, alcoholic, mad, wild, angry, violent, misogynistic…and yet also a deeply sensitive poet, a man who fell hard in love with women and had his heart broken badly many times, a man who lamented for years the death of his girlfriend, a man who could lay down poetry lines so accurately capturing the human condition that Shakespeare might be awestruck were he alive today, an insecure, emotionally needy, self-conscious man (surprise surprise: He was a writer!) who all his life searched for self-love, self-fulfillment, acceptance, love and praise.

I think it’s this above all else which captures hearts and minds, both in academia, in the literary world at large, in hipsterism, and in the world in general. He simply (and authentically) nails something so concretely, so absolutely, comically human, that to ignore it would just make you feel foolish. A deeply wounded, psychologically cracked, flawed human being, Buk possessed the ability to magically transform that inner struggle (and outer suffering) into Art.

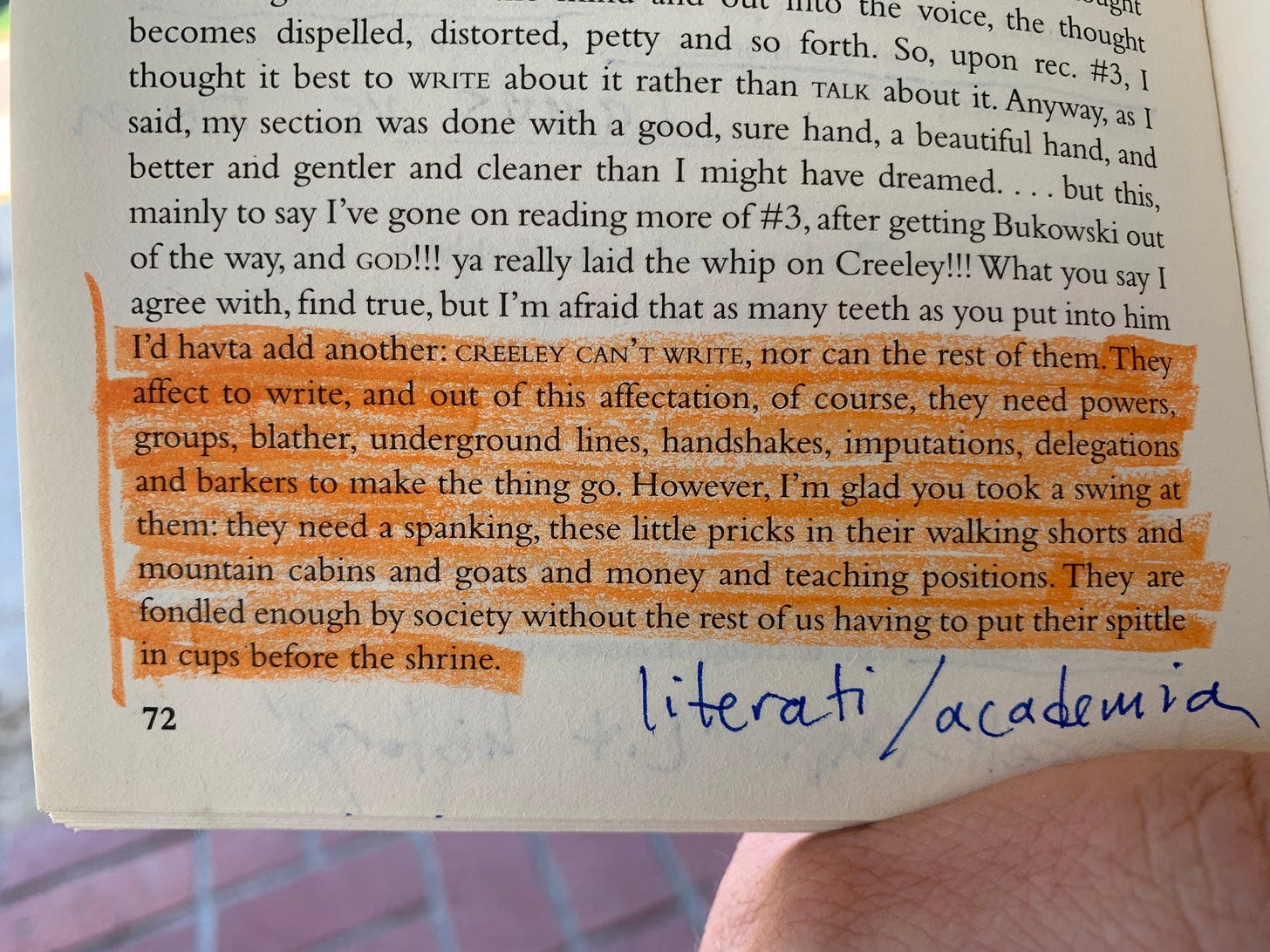

One of course must separate the artist from the art, especially in this case. In reading Howard Sounes’s Locked in the Arms of a Crazy Life, a Buk biography, I came away feeling a strange mixture of disgust, revulsion, deep respect and total awe for the man who had supposedly ripped literature back from the greedy hands of the academics and placed it back squarely into the hands of The People, where it had rightly always belonged well into the 19th century. (Sadly, literature has since become the effete domain, at least in traditional circles, of the MFA-glazed boring elite milieu.)

Buk got away—at least with many millions of readers—with his sardonic messiness on the page and in life because he truly was a “real” artist. He wanted to make money, and he desperately wanted notoriety and fame, but deeper than all that was the prose, the art. Also, he was a rebel and an outsider, and people either fear that or admire that. Me? I admire it. I feel in many ways simpatico. I grew up loving Kerouac and the Beats, and they’re great, but they had a sort of trendy cool-kid crew, and they became famous as a group: Kerouac, Ginsberg, Burroughs, Ferlinghetti, McClure, etc. (And they unintentionally started off the hippie movement of the 1960s, which Kerouac rejected.)

But Buk had no crew, no tribe, no group, no in-crowd. He was his own man. A loner. A drunk. He was vehemently anti-MFA and anti-academic; he thought most of that noise was fraudulent, and in many ways I think he’s right. What mattered for Bukowski was balls; guts. Guts, honesty, and realism. Hemingway told us to bleed on the page, but he himself never really did. He held back too much; he played it safe; he got too caught up in his own image. (Ditto Kerouac.) Buk was different. He believed a writer must write alone, in solitude. It was the writer against (or with) his typewriter, his mind, and four walls. Food wasn’t even necessary, just cigarettes and beer. Kerouac was like me: of the middleclass, slumming around with the wonder jail-kid Neal Cassady, fighting against a world that wasn’t really [fully] against him.

Buk was a contemporary of the Beats; all those guys were born in the 1920s. Children of The Depression. Buk got his ass kicked by his father as a kid, growing up in Los Angeles, where he lived most of his life after years spent bumming around the country in rooms across America. In his 20s he wrote short stories. In his thirties he wrote poetry and submitted to magazines just about everywhere in the country. At 50 he published his first novel, Post Office. He [largely] lived the life he wrote about. Put Buk in a similar slot as Henry Miller, Philip Roth, Flaubert, Dostoevsky, etc. (More Miller than Roth; Roth was a middleclass Jewish kid who was pampered.)

The thing is: Buk saw writing, saw literature as a necessity. It was his form of inner creation being spilled out into the external. Writing was his holy grail, the one thing that was always there for him, that never ruined him. Unlike booze, women, jobs, men, society, cops. Nabokov and Hemingway were actual boxers, but they were also rich kids. Buk wrote about the underground most people didn’t know existed because he actually came from it. Sure, he changed, altered, exaggerated some of his prose; of course he did. He was a writer, just like any writer; a man telling 75% truths mixed in with convenient lies to serve the story. Isn’t that what we all do?

Even though I was a rich kid from Ojai, California (north of Los Angeles), in many ways I lived a somewhat parallel life as Buk during my drinking years (2000 to 2010, age 17-27). Alcohol took me to some dark places, from blacking out, waking up with strange women in strange places, to violence to hopping trains to sleeping around to diabolical rage, anger, estrangement from friends, family and society as a whole. Sometimes I blacked out for days at a time, ended up in cities I didn’t know, got into fights with men I didn’t remember even seeing. Broke into vehicles for the fun of it. Found myself in a stolen car. I crashed probably a dozen cars during that decade, totaling half of them. I got fired from jobs left and right, or walked out on them.

Like Buk, I moved around constantly. In 2008 alone I moved five times all within San Francisco. There were a wild, booze-soaked few months in Santa Cruz, and ditto Philly, not to mention NYC, Portland and Oakland. I was a drifter, a drunk, a madman when I drank. Yet, unlike Buk, I always worked, always had mom and dad, always had some hazy form of stability. But I can relate to his lifestyle. I even remember hanging out with bums, buying them beer, or even having them buy us beer when we were in high school. I never liked school. I preferred solitude, casual sex, alcohol, reading and writing. When I finally did go back to college for Creative Writing, in 2012, two years sober, I was later accepted into the MFA writing program but last second declined it. I was a writer “of the streets,” I ironically told myself; not of the classroom.

Buk was in many ways a lazy man. He couldn’t hold down a job very long, except for 12 years at the post office. He didn’t work hard. His only goal in life was to stay drunk, find a woman for a while, and put down true, dangerous lines. His level of honesty—not always literal honesty in the sense of nonfictional reporting of How Things Were—was more emotional than logical. Much of what he wrote about happened or close, but beyond that was his experience of it. That’s one of Buk’s powerful achievements, too: With very little inner world-creation, he nonetheless manages to make us feel deeply.

We feel his humanity because he is a human being, and because he’s being tough and vulnerable at the same time, and because he’s saying Fuck It and tearing back the curtain, showing us who he is and, by extension, who we are. That’s his talent. That’s his raw meat. Whether Bukowski is a “good” man or a “bad” man is irrelevant; the point is that he is a man. We’re all guilty, really; none of us behind closed doors is wholly innocent. We all have those inner contradictions, those opposing and competing drives and desires, defense mechanisms, etc.

Buk had a hell of a lot of self-awareness, which is also ironic. He didn’t try to hide the fact that he was what he was, which often was fairly despicable. He understood something lost, forgotten, but crucial about Art: it’s not about being “good,” it’s not about “community,” it’s not about any specific ideology (fuck off with your “literary citizenship”), it’s not about being safe or polite or kind. Art—true art—is an expression of the inner complex turmoil which is the Human Condition. Rarely can a writer truly “open up and bleed.” Were Buk a musician he’d surely have been Iggy Pop. (Perhaps a little closer even, at times, to G.G. Allen.)

I have no compunction to fully defend Buk, his personal life or his writing. I respect his stuff; I think it will speak to many generations to come. He might be something like the 20th century working-class Walt Whitman. There’s a reason we still talk about, teach and read The Iliad. While Buk was no Homer, I do think he landed on something universal, that being the yawning void between society and man, system and individual, creator and group, artist and machine, outsider and the herd. A Picasso—or, more, a Van Gogh—misunderstood and yet simultaneously loved and admired, even when not completely grasping why.

There is plenty to criticize Bukowski about, from some of his bad, weak writing (he was beyond prolific and not all of it was good), to his shameless womanizing to his terrible work ethic, to his self-mythology and exaggeration of his own unique life, to his alcoholism, and much more. He was not what we’d call a stand-up guy. He was outside of the conventional circle of things. That’s what made him tick; that’s what made him matter. That’s what gave him a voice.

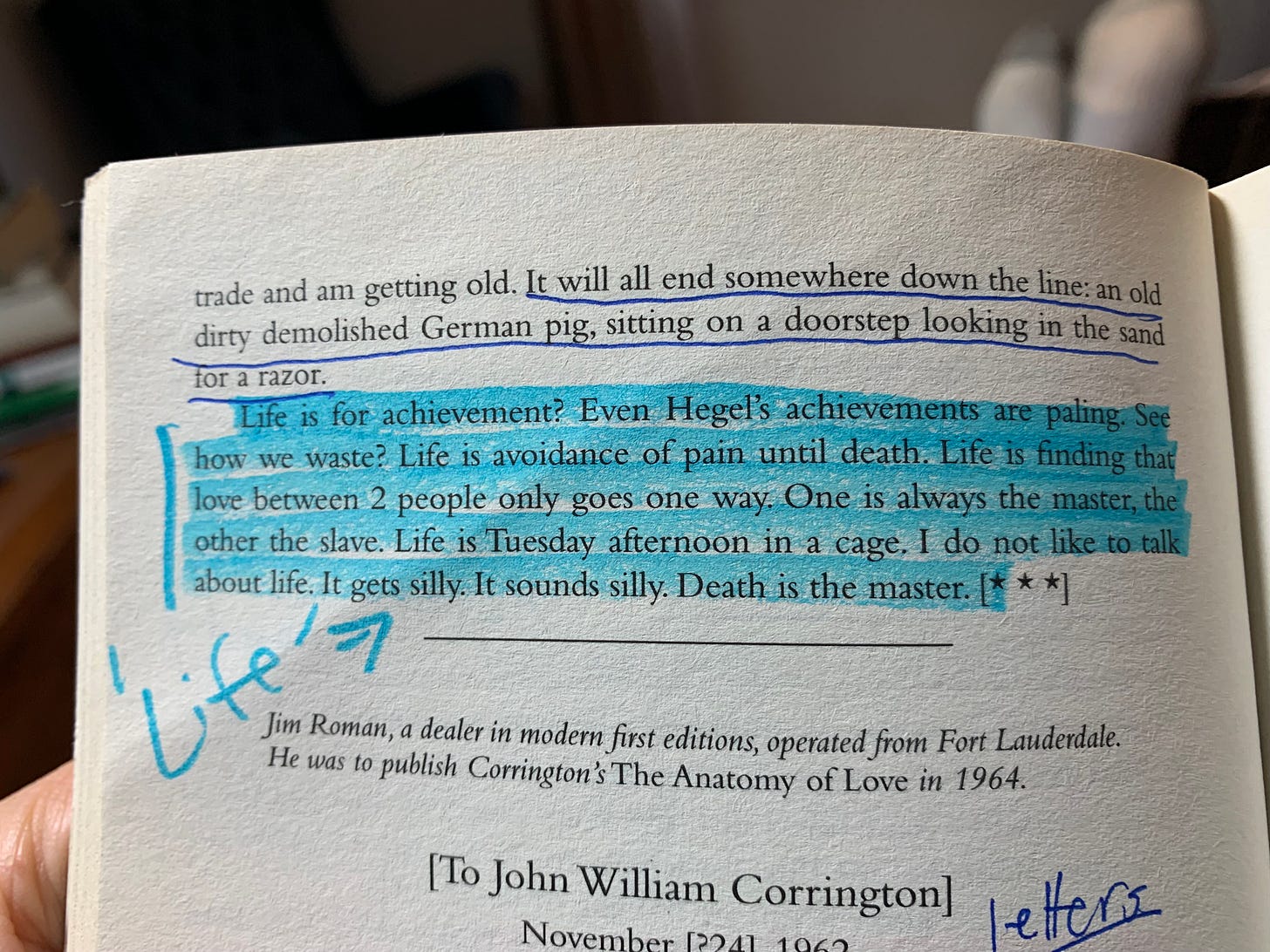

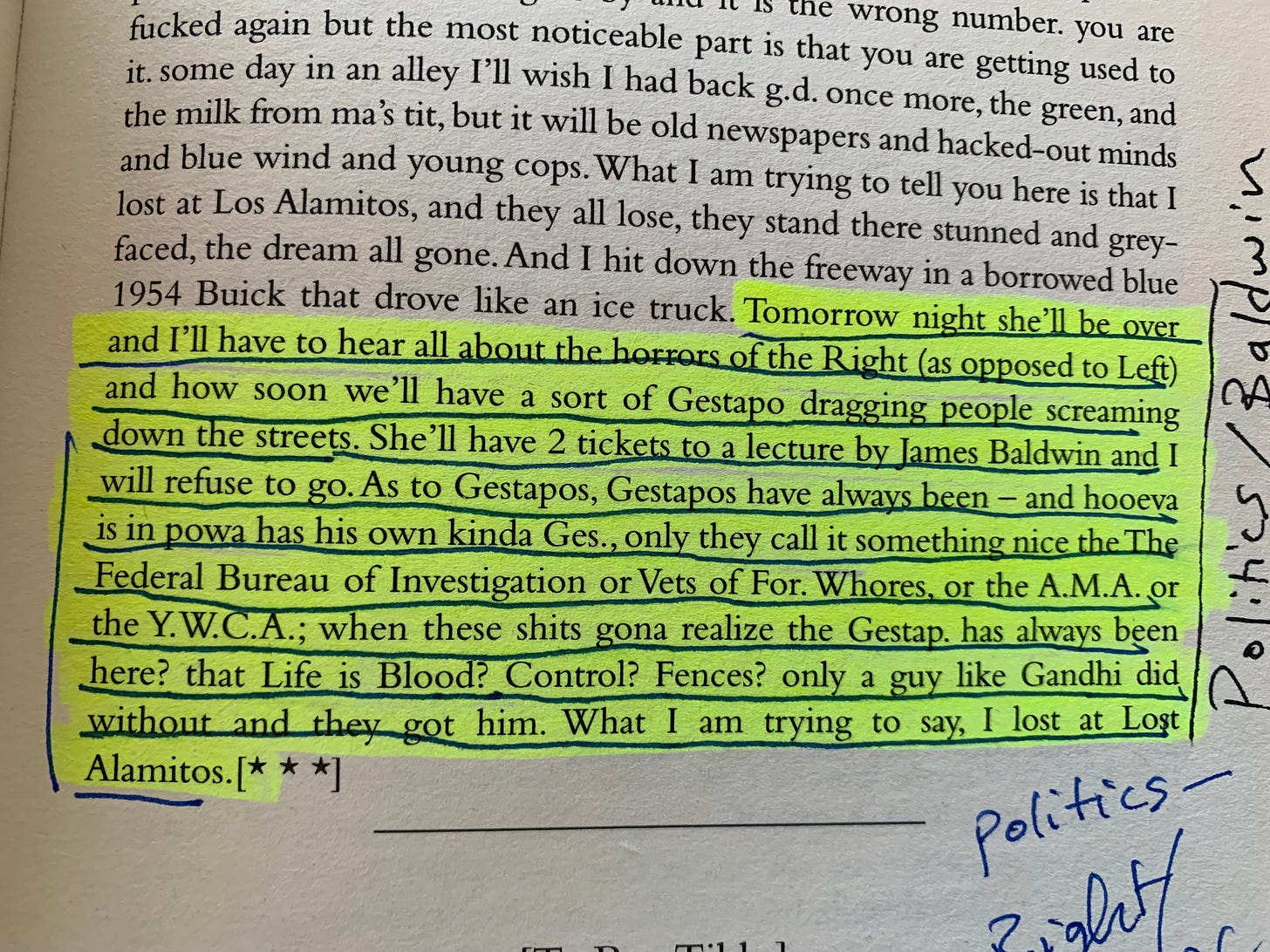

He wrote best when half drunk and alone. Read Notes of a Dirty Old Man; it’s some of his strongest stuff, and he didn’t actually put that much effort into it. As he himself wrote, he opened the beer and it just kind of came. He had a way with truth and honesty, a way with cutting through the gaudy, glittery bullshit and landing at What Is, a way of locating the gritty realism of things. That’s what drew readers to his work.

There’s been a lot of pushback the past 15, 20 years around the whole Tortured Artist Myth, the idea many male authors had in the 20th century—Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Cheever, Kerouac, Bukowski, [D.F. Wallace], Burroughs, etc—that in order to create important, impactful prose (Art) one had to drink, be on drugs, be high, fucked-up, loaded, etc. One had to possess a messy, jacked-up, even tragic life.

I don’t know about all that. I myself didn’t really seriously start writing until I stopped drinking, in 2010. Before that I wanted to write but I was a blackout drunk; I’d open a beer and start writing on the laptop and the next thing I knew I woke up the next morning with bruises and gibberish on the screen. I had to get sober in order to tap into my own creative reserve.

I don’t know what Buk would have given us had he been sober. I wish he’d have tried. He decided in his younger years that he wasn’t an alcoholic and didn’t need AA because he could “stop if he really wanted to.” (I highly doubt this.) And yet, perhaps he did need the booze. Perhaps they all did. Maybe; maybe not.

I do think it’s a general truth that most serious, talented writers are “messed up.” Not fuckups; not broken people; not pieces of shit. Not bad. That’s not what I mean. I just mean semi-broken, wounded, to some degree feral creatures. It takes a certain kind of mind and disposition to be a writer. Sensitivity, sometimes to an extreme degree. Self-consciousness (David Foster Wallace wrote wonderfully about this.) Insecurity. A full connection to a deep, rich inner life. A sharp and strong imagination, which sometimes feels bigger and more crucial than “real life.” Often a disdain for convention and for the normative values of any given society. A harsh need to be on one’s own, to follow one’s own path, to blaze one’s own trail, to forge one’s own inner fire.

Not every writer is like this but I’ve noticed over the years that most of them more or less fall roughly into these categories. This is what makes them (us ) writers. Writers generally aren’t the insiders, holding hands with everyone else; we’re the outsiders doing our own weird inexplicable thing. This is why the others read our work; they’re fascinated by the roadside car crash, with all its suffering and psychological education.

And so surely, given these general traits, one can easily see how alcohol, drugs and anything else which can loosen the tight screws in your brain, would be attractive to artists, to writers in particular. To numb out, to let loose a little, to tamp down the voices inside, to feel less alone, to feel more connected. Whether this helps or hinders the creative act I cannot answer.

Buk died in 1994, at the age of 73, of Leukemia. He lived almost his whole life in Los Angeles. He became a Los Angeles writer. One of a kind. There’ve been a zillion copycats since he died, but none of them compare to the king. A Boomer writer who has a similar creative viewpoint—but not style—would be Denis Johnson. That gritty, dark realism many of us crave. (And one can’t help but think of an LA author who came before Buk who also eschewed the inner world of the narrator in exchange for style and aesthetic nuance, yet who failed when compared to the beauty of Buk’s literary lines: Raymond Chandler. Chandler wrote gorgeously, but he wasn’t writing strictly “literature”; he wasn’t trying to nail down the human condition, attempting to tangle with meaning and depth, only telling a lovely, stellar, sticky and compelling story.)

Whether Buk was drinking alone in an alley in LA somewhere, sitting at a bar at noon on a Wednesday, betting on the horses at Santa Rita, schmoozing some woman far too beautiful for his pockmarked, scarred face, whatever he did he tried to do with style. Even his brief jail stints, and especially with his writing. He was all about depth and clarity. He’d have utterly failed the test of Orwell’s Politics and the English Language, but he wasn’t going for that, with his uncapitalized beginnings to sentences, his terrible use of comma-splices, his iffy, sometimes terrible grammar and syntax. He was going for authenticity. He was going for truth. He was going for rawness of spirit. He was going for spiritual crucifixion. Salvation. He knew he was doomed, from a very young age. Rejected. Outcast. Hated. Turned away. Gross. Hidious. Pathetic. What made him different is that he leaned into this and turned that into creation.

For me, I feel inspired not by Buk’s real life behavior—though sometimes, that—but by his outrageous sense of truth-telling, unpacking taboos (some of the most wrapped up ones), and spitting in the eye of people who claim that literature is to be learned in classrooms. Literature has always been of the streets. Still is. Rarely do you find it in academia or in traditional publishing, especially now. These days you find it on Substack or Medium or in random brilliant blogs.

The lesson of Bukowski is: Don’t think about it; just write it. Just tell it how it is. Stop “trying” to write or, worse, trying to “sound” like a writer. Simply put it down.

That’s the gem, the gift, the prize.

That’s Art.